| TED Case Studies -- Number 728 -- April 2004 -- by Milica Koscica |

1.

The Issue

Nearly three centuries ago, “the Cognac industry began to define

a code of practice that would preserve the identity and quality of the

spirit at every stage from production through the sales.”* The

overall procedure is distinct and highly controlled, accounting for

the special character of the spirit. Trade in Cognac dates back to the

17th century, when it was first produced in the region of Charente-Meritime

in France, an area the locals boast as having the ideal climate for

the special Ugni Blanc white grapes used exclusively in the production

of Cognac. Since then, Cognac has developed a global market and recognition

as a high-quality, luxury spirit enjoyed by the movers and the shakers

of the world. However, imitations and generic labeling have recently

threatened Cognac’s integrity and sales. As a result, the European

Union (EU) has added Cognac to its fast expanding list of geographically

distinct products it wishes to protect under the World Trade Organization’s

(WTO) Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs)

treaty. This case study plans to examine the uniqueness of Cognac by

looking at its history, production, and most importantly, its reputation

in order to explore why it merits a protected geographic indication.

*Burreau National Interprofessional du Cognac

2.

Description

What is Cognac?

As the saying goes, all Cognac is Brandy, but not all Brandy is Cognac.

Cognac is a distilled spirit (eau-de-vie) made from fermented white

grapes, and aged for at least two years. The spirit can only originate

from the town of Cognac, France, and its six surrounding viticultural

areas. Cognac is unique because of its renowned quality, which is in

turn a result of centuries-old techniques that have preserved the identity

of the spirit. The process of creating Cognac is extremely controlled,

and it adheres to strict rules and regulations. For instance, only natural

grape presses can be used to make the spirit. The grapes themselves

are special because of the chalky soil where they grow, and the soil

is in turn special because of the unique climate created as a result

of the Atlantic Ocean. Also, because the aging process is just as important

as the actual distillation of the grapes, even the type of wood used

for the storage barrels is predetermined and controlled. Only the 60-100

year-old Oak trees in France are deemed worthy for the job. Lastly,

tradition and culture play a huge role in the process because each Cognac

house has preserved its family secrets for generations. Lets explore!

History

The history and production of Cognac is directly related to trade. The

town of Cognac, France, has always been linked to important international

trade routes through the river Charente, which gave the small town easy

access to the Atlantic Ocean. During the 16th century, the Dutch merchants

used to ship salt and wine from the Southwestern parts of France to

northern European countries such as England, Scandinavia, and The Netherlands.

However, the merchants soon encountered a problem: the delicate white

wine would often spoil during the long voyage. To protect the quality

of the wine, the merchants began to distill it, and they named it Brandewijn

or ‘burnt wine.’ This became the forerunner of Brandy.

During the 17th century, the people of Cognac, the Cognaçais, began the process of double distillation, which allowed the concentrated alcohol to travel in the safer and the more economical conditions. Initially, this alcohol was to be diluted immediately upon arrival. However, it is merely by chance that the Cognaçais discovered that the alcohol improved with time and contact with the oak barrels in which it was stored. Soon enough, they began to drink it straight from the barrels. The name given to the new product was Cognac.

The

Delimited Areas

All Cognacs originate from Cognac, France, and the six growing areas

surrounding the town. In 1909, the French government defined the boundaries

of the

Cognac production area by a decree that covered the region of Charente-Meritime,

part of Charente, and several municipalities in Deux-Sevres and Dragone.

The entire delimited area covers 200 000 acres.

At the center of this 200 000-acre delimited area lies the town of Cognac. Surrounding the town and are six different viticultural areas, or crus, with each enjoying a specific climate and soil that produces different and complementary qualities of the spirit. For example, Cognac loses its sharpness and gains body as the production moves further from the center. The blending of these distinct qualities gives each Cognac its individual character and taste.

Climate

and Soil

The Cognac production area lies at a junction where a microclimate and

rich, diverse soil meet to produce the conditions that are favorable

for the cultivation of vines used to make the spirit. The microclimate

is a result of the influence of the Atlantic Ocean on the land. It is

characterized by being ‘softly tempered,’ with ample amounts

of sunlight and sufficient rain, and an average annual temperature of

13.5°C (48°F). This microclimate, combined with the special

soil, is considered ideal for the production of high quality wines.

The

secret of Cognac lies in the soil. Although the soil produces a wine

that is not particularly good, it is nonetheless ideal for distillation.

The soil itself is extremely diverse, ranging from open country chalky

soils, to plains with red clay earth, to green valleys. Quality variations

in the soil are based on the amount of chalk present, the hardness of

the chalk, and the amount of clay mixed in with the chalk. For example,

more chalk in the soil increases its quality; the softer the chalk,

the better; and the less clay in the soil, the better its quality. Chalk

in the soil is important because it retains humidity (moisture). Also,

the chalk- flecked

soil reflects light and so helps to ripen the grapes. Grand Champagne

has the softest chalk and the least clay; therefore, it is considered

the best soil and produces the highest quality Cognacs.

flecked

soil reflects light and so helps to ripen the grapes. Grand Champagne

has the softest chalk and the least clay; therefore, it is considered

the best soil and produces the highest quality Cognacs.

The

Grapes

The grapes used in the production of Cognac are themselves covered by

a decree, and come from the white wine varieties

– specifically the Ugni Blanc, Folle Blanche, and Colombard. The

Ugni Blanc is chosen for its late maturing and its ability to resist

disease, while the Folle blanche and the Colombard are selected due

to their thin white wine that are deemed good only for Cognac. All the

varieties of grapes used in the production are grafted onto various

vine stocks selected according to the type of soil.

The Process of Making Cognac

I.

The Harvest

The

harvest takes place in early October. By this time, the grapes have

attained their aromatic maturity, or “the moment when they embody

the very nature of the soil from which they have grown” (Remy

website). Over the years, there have been some changes in

The

harvest takes place in early October. By this time, the grapes have

attained their aromatic maturity, or “the moment when they embody

the very nature of the soil from which they have grown” (Remy

website). Over the years, there have been some changes in the cultivation techniques in order to accommodate modern Cognac demand

in international trade. For example, the vines are now planted further

apart – tree meters apart – in order to allow mechanical

pickers to pick the wine. One machine/tractor can match the labor of

sixty human workers.

the cultivation techniques in order to accommodate modern Cognac demand

in international trade. For example, the vines are now planted further

apart – tree meters apart – in order to allow mechanical

pickers to pick the wine. One machine/tractor can match the labor of

sixty human workers.

II.

Pressing and Fermentation

Immediately after harvesting, the grapes are pressed in the traditional

horizontal plate presses or in pneumatic presses. Continuous presses,

using the Archimedes’ screw press, are prohibited because they

might damage or bruise the grape skins, which would ultimately add bitterness

and extra acidity to the Cognac. Also during this stage, the grape pips

must be removed when pressing the grapes in order to eliminate the tannins

in the pips because they can damage the final distilled product.

As soon as the grapes are pressed, the grape juice is left to ferment.

Fermentation is natural - the native, wild yeasts are allowed to convert

the sugar into alcohol. The Decree of May 15, 1936, forbids chaptalization,

or adding sugar to the process in order to increase the alcohol level

of the wine. Additionally, the fermentation takes place without the

addition of antioxidants or of sulfur because sulfur would emerge as

an undesirable element in the final brandy. Fermentation usually lasts

from two to three weeks. At this point, the wine is quite delicate and

must be distilled while it is still fresh. This is why Cognac regulations

require the distillation from a harvest to be completed by March 31st

of the following year.

Because the wine is low in alcohol, about 10 gallons of wine are needed

to produce one gallon of Cognac. The Charente wines typically have from

7 to 8% alcohol (compared to the normal table wine level of 10-14%).

This wine is quite undesirable because it is thin and acidy, but it

is nonetheless perfect for distillation.

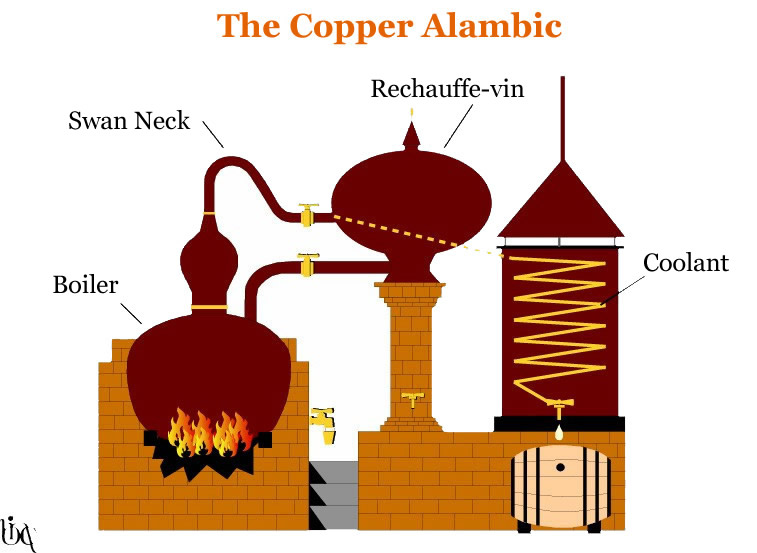

III. Distillation

Cognac would not deserve its grand reputation if it were not for the

alchemy that takes place in the pot stills during distillation. It is

this process of double distillation that finally turns the white wine

into an eau-de-vie. The  method

of double distillation has not changed over the centuries: only the

Charentais pot still, or the ‘Alambic,’ is allowed for the

process. The Alambic is made up of an onion shaped boiler that is heated

with an open flame. It is entirely made of copper “because copper

has a catalyzing effect and it does not affect the taste of the spirits.”

The bottom of the main cauldron, where the liquid to be distilled is

placed, is in permanent contact with the open flame of the furnace.

It is important to keep the wine uniformly heated over a large surface,

and so the boiler capacity must not exceed 30 hectoliters. There is

also a ‘swan-neck’ tube, which leads the wine off from the

boiler and then turns into a condensing coil, which passes through a

cooling tank known as ‘the pipe.’

method

of double distillation has not changed over the centuries: only the

Charentais pot still, or the ‘Alambic,’ is allowed for the

process. The Alambic is made up of an onion shaped boiler that is heated

with an open flame. It is entirely made of copper “because copper

has a catalyzing effect and it does not affect the taste of the spirits.”

The bottom of the main cauldron, where the liquid to be distilled is

placed, is in permanent contact with the open flame of the furnace.

It is important to keep the wine uniformly heated over a large surface,

and so the boiler capacity must not exceed 30 hectoliters. There is

also a ‘swan-neck’ tube, which leads the wine off from the

boiler and then turns into a condensing coil, which passes through a

cooling tank known as ‘the pipe.’

The process of double distillation has two steps (of course!). In the first stage, the first distillate is obtained, known as the ‘brouillis,’ which contains an alcohol level of 28% to 32% volume. The ‘brouillis’ (which is a cloudy liquid) is obtained by boiling the unfiltered wine, and then having the alcoholic vapors pass through the swan neck to finally condense when they come in contact with the cool air in the coolant or ‘the pipe.’ The entire first heating, or the first ‘chauffe’ lasts between 8 and 10 hours.

During

the second stage, the ‘brouillis’ is returned back to the

boiler for a second heating known as the ‘la bonne chauffe.’

It is during this second heating that the eau-de-vie, or the spirit,

is finally extracted from the liquid.  Here,

the distiller performs a delicate process called ‘cutting’

by separating the ‘heart’ from the ‘heads’ and

the ‘tails.’ During the process, the vapors that arrive

first (the heads) have too high of an alcohol content, and so they are

cut off and separated from the rest of the liquid. The next batch of

liquid is the ‘heart,’ or a colorless liquid with a 70%

alcohol per volume. The great task of the distiller is to keep only

the heart of the second distillation, which ensures that only the purest

spirit will be used to make Cognac. The ‘tails’ are then

cut off as well because their alcohol content is too small. Ultimately,

the heads and the tails will be ‘redistilled’ in a subsequent

batch. The entire process lasts approximately 12 hours.

Here,

the distiller performs a delicate process called ‘cutting’

by separating the ‘heart’ from the ‘heads’ and

the ‘tails.’ During the process, the vapors that arrive

first (the heads) have too high of an alcohol content, and so they are

cut off and separated from the rest of the liquid. The next batch of

liquid is the ‘heart,’ or a colorless liquid with a 70%

alcohol per volume. The great task of the distiller is to keep only

the heart of the second distillation, which ensures that only the purest

spirit will be used to make Cognac. The ‘tails’ are then

cut off as well because their alcohol content is too small. Ultimately,

the heads and the tails will be ‘redistilled’ in a subsequent

batch. The entire process lasts approximately 12 hours.

IV.

Aging

An eau-de-vie can only become Cognac after it has slowly matured in

oak casks. The wood that is used to create the casks comes from some

of the 100-year-old Oak trees in France. The casks are made in a traditional

way, where the wood is burned to be bent into a cask, and it is only

cut with the grain, never against it, to ensure water tightness. Oakwood from the Limousin and Troncais forests is selected

for its hardness, its porosity, and its extractive characteristics.

For example, the Tronçais forest provides soft, finely grained

wood, which is particularly porous to alcohol. The Limousin forest produces

medium grained wood, harder and even more porous.

tightness. Oakwood from the Limousin and Troncais forests is selected

for its hardness, its porosity, and its extractive characteristics.

For example, the Tronçais forest provides soft, finely grained

wood, which is particularly porous to alcohol. The Limousin forest produces

medium grained wood, harder and even more porous.

The aging process takes place entirely in these oak casks, which are then stored in dark cellars, called ‘chais’, where the Cognac will mature for at least two years. The dryness or dampness of an individual producer's chais will effect the characteristics of the eau-de vie as it matures. In reality, producers move casks “around the chai or from one chai to another as the spirit develops in order to promote the optimum development of aroma and flavor.”

One of the crucial phases of the aging process is called extraction, during which the wood transfers its tannin to the newly distilled colorless spirit, thus naturally giving it its characteristic amber color. The Tronçais tannins are particularly smooth, whereas the Limousin wood is prized for the strength and balance it imparts to the Cognac.

Furthermore,

the oak wood, because it is porous, allows for a permanent yet indirect

contact between the Cognac and the surrounding air in the cellar where

the casks are stored. Consequently, Cognac will lose some of its alcoholic

content due to evaporation (about 3%). This evaporation leaves a dark

hallow over the walls of the cellar, which has been dubbed The Angels’

Share. A microscopic fungus called torula compniacensis Richon develops

due to the mixture of the humid air and the evaporated alcohol. Interestingly,

these ‘Angels’ drink approximately twenty million bottles

of evaporated Cogac each year, making them the second largest market

for the sprit after the United States!

Furthermore,

the oak wood, because it is porous, allows for a permanent yet indirect

contact between the Cognac and the surrounding air in the cellar where

the casks are stored. Consequently, Cognac will lose some of its alcoholic

content due to evaporation (about 3%). This evaporation leaves a dark

hallow over the walls of the cellar, which has been dubbed The Angels’

Share. A microscopic fungus called torula compniacensis Richon develops

due to the mixture of the humid air and the evaporated alcohol. Interestingly,

these ‘Angels’ drink approximately twenty million bottles

of evaporated Cogac each year, making them the second largest market

for the sprit after the United States!

Lastly, it must be noted that while the legal ‘age limit’ on Cognac is two years, in reality most of the Cognacs are aged for much longer (up to fifty years or more) in order to increase the quality of the spirit.

V.

Blending

The last step in the process truly determines a particular Cognac’s

ultimate taste, aroma, body, and even label. It is at this point that

the Master Blender, or the person with a wealth of experience in charge

of the maturing process, determines which Cognacs will be mixed in order

to create the ultimate flavor. You see, Cognac does not simply consist

of a single year’s distillation, but is instead a complex mix

of many different Cognacs ranging in years, and sometimes even the crus.

Each Cognac house has its own Master Blender, and his or her secrets

are fiercely guarded because they control the ‘personality’

of a particular Cognac.

Remy

Martin, one of the more recognized Cognac houses, describes their Master

Blender’s delicate work in quite some detail: "The

Cellar Master begins his art. He fills his glass one-third full, leaving

room for the aromas to develop. Then he uses his nose to test its vintage

and bouquet. He takes a little in his mouth to try its body and mellowness.

His senses awaken one by one as he continues the ritual. Unconsciously,

he closes his eyes as he sniffs. As his eyes open, he focuses on the

color of the Cognac. This is the moment when the Cellar Master decides

what will be used in the final blend."

The blending is one factor that determines the ‘value’ of a Cognac, which is in turn identified by the Cognac label. The age of the Cognac shown on the label matches the youngest Cognac used in the blend.

As Cognac ages, it gains its distinctive amber color. This diagram shows the colors as they correspond both with the age and the label of the spirit.

3. Related Cases

1.

Scotch:

Scotch: The Culture of the World's Leading Spirit

2. Grappa:

Who Owns Grappa: Name and the EU-South Africa Trade Agreement

3. Budweis:

Who Owns the Name Budweiser?

4. Cassis:

Cassis Spirit Trading

5. Chocolat:

EU's Chocolate Dispute

6. Feta:

Feta Cheese

7. Pisco:

Pisco Liquor Dispute between Chile and Peru

8. Germbeer:

German Beer Purity Law

9. Tequila:

Tequila: Trade, Culture, and Environment

10. Cachaca:

Brazilian Fire Water

11.

Kentucky Bourbon:

Kentucky Bourbon and Protection as a Geographic Indication

12.

Tennessee

Whiskey: Tennesse Whiskey and Protection as a Geogrpahic Indication

13.

Polish Vodka:

Zubrowka: Polish Vodka and Cultural Georaphic Indicators

14.

Canadian Whiskey:

Canadian Whiskey and Protection as a Geographic Indication

15.

Mezcal: Mezcal

and Protection as a Geographic Indication

4. Author and Date

Milica Koscica, April 2004

Cognac’s name is fiercely guarded and protected on multiple levels. For instance, the Cognac Appellation of Origin (A.O.C.) is a geographical indication recognized both under the French law and the European Union Council Regulation (EC) 1576/89. Furthermore, Cognac A.O.C. fulfills the requirements under Article 23 of the Agreement of Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS) of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Article 23 of TRIPS states that each member of the WTO has the obligation to protect the geographical indication of wines and spirits by preventing the use of a name for a spirit if that spirit does not originate from the location indicated by the geographical indication. Article 23 is ruthless in terms of protection because it states that a geographic indication cannot be used even in translation or if it is accompanied by “expressions such as ‘kind,’ ‘type,’ ‘style,’ and ‘imitation.” To be sure, the Cognac industry has done everything in its power to make sure that the members of the WTO abide by the rules and protect Cognac from imitations and homonyms.

The

Issue:

In 1997, the French Bureau National de Interprofessionnel de Cognac

(BNIC) issued a complaint against Brazil for three reasons: a) the lack

of protection of the Cognac Appellation of Origin (A.O.C.) in Brazil,

b) the extremely complex and unusual licensing system, and c) discriminatory

taxation.

The effort to protect Cognac came as a result of trade disputes over a variety of spirits that are collectively called conhaque in Brazil. The Brazilian conhaque market currently consists of both wine based spirits, including Cognac (0.09%), and sugar cane based spirits (90%). According to the EU, the Brazilian conhaque drinks are lower in standards and quality than Cognac, and therefore they damage the reputation and confuse the consumers as to what the term ‘Cognac’ really means. For instance, in contrast to Cognac, there are no specific standards on the production or the aging process for the variety of spirits that collectively fall under the term conhaque.

Because these spirits can be made at a much lower cost, they can also be sold for less, and according to BNIC, if the consumer must choose between a relatively expensive French Cognac and the cheaper conhaque, he or she will opt for the less expensive drink without ever knowing the difference in quality. This in fact has had an enormous negative affect on Cognac sales in Brazil. Additionally, the EU claims that the exports of generic conhaque threaten the marketing and sales of Cognac in developing markets around the globe, such as India and Russia, where Cognac’s reputation has not yet been established. BNIC claims that the Brazilian lack of protection of the appellation of origin for Cognac violates Article 23 of the TRIPS and Article 12(2) of the 1992 EC-Brazil Framework Agreement (a contract where both sides agreed to respect each other’s intellectual property rights, including geographical indications and appellations of origin).

The

Mechanism:

Bureau National de Interprofessionnel de Cognac (BNIC) was able to issue

its complaint against Brazil through the Trade Barriers Regulation (TBR)

mechanism, which is one of European Union’s commercial policy

instruments that allows individual companies or industry groups access

to their rights under the WTO. The TBR covers trade barriers that are

forbidden under international trade rules, mainly those under the WTO,

including rules regarding intellectual property. The TBR procedure to

issue a complaint has three steps. If trade is being negatively affected

by obstacles posed from a third country, then EU member states, industry

groups, or individual companies have the right to issue a formal complaint

to the European Commission for investigation. To be considered, the

complaint needs to be supported both by factual and legal evidence that

a WTO rule of trade is being violated by a third country. If the Commission

finds substantial evidence of a violation, one of two things can happen.

First, the Commission will launch bilateral talks with the offending

country’s government in hopes of resolving the issue and finding

mutually acceptable solution. Second, if bilateral talks do not succeed,

then the Commission will take the complaint to the WTO Disputes Settlement

proceeding. More often than not, the problems are solved bilaterally

between the EU and the third country without the involvement of the

WTO.

In the case of Cognac, the Commission investigation confirmed the lack of protection of Cognac’s A.O.C., and therefore initiated bilateral talks with Brazil that ended positively.

Outcome:

Following various bilateral negotiations, the Brazilian government eventually

agreed to protect Cognac’s A.O.C., and Cognac’s geographical

indication was registered on April 11, 2000. Even though the domestic

conhaque industry objected, Brazilian authorities decided to settle

the issue without entering the dispute settlement procedure under the

WTO. The registration of Cognac’s geographical indication gave

the French producers exclusive rights to use the term Cognac, prohibiting

the term to be used as a generic name. All existing products with the

registered trademark of Cognac will be phased out by year 2005. Similar

agreements have been made in bilateral talks between the EU and Chile

where Chile will have to phase out all products named cognac within

the next decade. However, the term conhaque was allowed to stay in use

due to TRIPS Article 24, which states that once a term becomes a generic

name in a domestic market, as the Brazilian authorities claim for conhaque,

it cannot be registered as a trademark. Also, as long as the generic

term is not misleading consumers or as long as negotiations aiming at

phasing out the use of the term are still in place, Brazil can use conhaque

to label different spirits. Therefore, the geographical indication of

Cognac will have to coexist with the generic term conhaque. The European

Court of Justice has deemed the outcome satisfactory, but it has nonetheless

stated that further protection of Cognac against the generic term conhaque

can be pursued in the future if appropriate as deemed under TRIPS Article

24. It looks like the issue may not be completely resolved after all.

5.

Discourse and Status: Disagreement and

Complete

6. Forum and Scope: EU and Regional

7. Decision Breadth: EU (France) and

Brazil

8. Legal Standing: Treaty

9.

Geographic Location

a. Geographic Domain: Europe

b. Geographic Site: Western Europe

c. Geographic Impact: France

10. Sub National Factors: Yes. Cognac, France.

11. Type of Habitat: Temperate

![]()

**Figures relative to Cognac trade are mostly expressed in hectoliters of pure alcohol. To make the understanding easier, figures and graphs relative to the shipments of Cognac will be expressed in millions of bottles, where 360 bottles equal one hectoliter of alcohol. In 2003, 127.3 million bottles of Cognac were shipped worldwide, which amounted to some €1.2 billion Euros in revenue. The key exporter of Cognac was France, and the key importer was the United States. **

Since all Cognac should theoretically originate from the town of Cognac, France, the French are understandably the largest exporter of the spirit. In 2003, France sold 127.3 million of bottles of Cognac, where 6.5 million were sold at home and the rest were shipped to foreign markets. Essentially, 94.9% of Cognac was exported, which contributed approximately €1.2 billion Euros ($1.5 billion USD) to the annual trade surplus in France. Since Cognac’s main markets are outside of France, geographic indication plays a vital role in protecting Cognac quality and reputation in these foreign markets. Without geographic indications, Cognac might lose market share to cheap imitation Cognacs in different countries, and therefore Cognac producers back in France might lose the greatest source of their revenue. Currently, according to BNIC, the Cognac industry in Cognac, France, employs directly 21,000 people, and more than 55,000 people are indirectly involved either through the botteling, labeling, cork, carbord, and insurance industries.

In terms of geographic distribution, the three main markets for Cognac in 2003 were North America (42% of sales), Europe (40% of sales), and Asia (18% of sales). More specifically, the largest importer of the spirit was the United States, with 49.1 million bottles of Cognac imported from France. Cognac sales in the US have nearly tripled since 1993, and the US has remained the top Cognac importer for the past ten years (Figure 1). The US market brought in approximately €530 million (USD $653 million) in revenue to France in 2003.

Figure 1

United States Cognac sales in the last ten years

Interestingly enough, one of the reasons for this momentum is Cognac’s new and fast-expanding market in the mainstream Hip-Hop urban culture. Different types of Cognac brands, including Remy Martin, Hennessy, and Courvoisier, have been benefiting from exposure in pop-hit music videos with rap stars like Eminem, Busta Rhymes, and others. To traditional Cognac connoisseurs, Cognac’s new hip-hop image was shocking, but the phenomenon was welcomed because it ultimately helped resurrect the Cognac industry after the devastating Asian economic crises in 1997.

As a luxury good, Cognac is sensitive to fluctuation in the global economic environment, and it is often the first to suffer from a lower household consumption in times of economic downturns (Figure 2). Cognac trade also experienced a marked low in sales in 2001, which resulted from the September 11 terrorist attacks in the United States. September's dramatic events provoked fears for the American market as well as for airport and travel related sales. However, over the past two years, Cognac trade figures have improved significantly. The initial alarm over the possible negative effects in the US market proved to be exaggerated since Cognac consumption in the US has steadily increased since 2001.

Figure 2

Worldwide Sales in the last ten years

Figure 2 traces the evolution of the worldwide Cognac sales over the past ten years. It shows Cognac’s sensitivity to global economic forces. The 1997 Asian crisis and the 2001 terrorist attacks correspond with lower sales of Cognac in two of its most important markets.

Top Ten Importers

12. Type of Measure: Intellectual Property

13. Direct v. Indirect Impacts: Indirect

14. Relation of Trade Measure to Environmental Impact

a. Directly Related to Product: Yes,

Cognac

b. Indirectly Related to Product: Yes, Grapes

c. Not Related to Product: No

d. Related to Process: Yes, Culture

15. Trade Product Identification: Cognac

16. Economic Data

17. Impact of Trade Restriction: None

18. Industry Sector: Food, Wines and Spirits

19. Exporters and Importers: France and Many

The Cognac industry is integrally linked to the environment where the spirit is created. Factors such as the location, the microclimate, the unique soil, and even the trees growing in the delimited area all contribute to the spirit’s taste, production and trade. Cognac producers are heavily influenced by the changes in the ecosystem, as was illustrated in late 1800s by the emergence of the phylloxera fungus that spread throughout the region nearly destroying the vineyards. Today, even though producers boast of tradition and stable climatic conditions, it is difficult to imagine that Cognac’s delimited area and special climate will be left unscathed by the changing environmental trends such as global warming. The impact of global warming on the production of Cognac poses a future concern that will need to be addressed by the next generation of Cognac producers. Right now, however, it is important to demonstrate how the region’s environment is involved in the production of the spirit.

Phylloxera

Near the end of the 19th century, a major crisis affected the grapes

grown in the region. A fungus called phylloxera spread throughout the

vineyards, slowly destroying the all the grapes. The disease attacked

the roots of the vine,  therefore

destroying the plant entirely. The French had used every imaginable

method to cure the grapes, including urinating on the vines and planting

toads among their roots. Then in 1888, after a decade of searching,

a French scientist named Pierre Viala traveled to Denison, Texas, where

he finally found a long-term cure to the disease. It was discovered

that the French vines needed to be partly grafted with healthy American

vines, and that new fertilizers needed to be used. Since then, the vineyards

have been entirely replanted, and phylloxera never again posed a problem.

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the cure for the disease, Denison,

Texas, and Cognac, France, became sister cities in 1988. For more infromation,

see the Vinewine

TED case study.

therefore

destroying the plant entirely. The French had used every imaginable

method to cure the grapes, including urinating on the vines and planting

toads among their roots. Then in 1888, after a decade of searching,

a French scientist named Pierre Viala traveled to Denison, Texas, where

he finally found a long-term cure to the disease. It was discovered

that the French vines needed to be partly grafted with healthy American

vines, and that new fertilizers needed to be used. Since then, the vineyards

have been entirely replanted, and phylloxera never again posed a problem.

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the cure for the disease, Denison,

Texas, and Cognac, France, became sister cities in 1988. For more infromation,

see the Vinewine

TED case study.

Something to Think About!

Can the town of Cognac, France, really claim geographical indication based on the unique properties of its soil and grapes if grapevines from Denison, Texas, were used to replant entire French vineyards?

Climate

Change

The possible impact of global warming on the Cognac industry cannot

be ignored. One study

of the world's top 27 wine regions’ temperatures and wine quality

over the past 50 years reveals that rising temperatures have already

impacted vintage quality. As for the next 50 years, climate modeling

for these same regions predicts a 2°C temperature rise. Gregory

Jones, the scientist at Southern Oregon University who performed the

study, claims that the warmer climate can have two possible consequences:

it can make some cooler areas more conducive to wine growing, and it

can make the currently warmer areas less favorable for vineyards. For

instance, these warmer regions could experience problems in terms of

overripe fruit, added water stress, and increases in diseases and pests.

However, the problem of climate change is not only ecological - it can also have drastic impact on the local culture. Jones claims that in the next 20 to 30 years some vineyards will be forced to replace their traditional grape varieties or change management strategies. The impact on culture and identity stemming from such changes is significant. "There is a huge historical and cultural identity associated with wine producing regions. A region known for a superb Merlot, for instance, might need to shift to another kind of grape, changing the cultural identity that has developed over centuries,” asserts Jones.

Even though Cognac is not wine, it nonetheless depends on the climate and on the grapes from which it is made. Cognac producers pride themselves on tradition and quality of their grapes that have remained stable for many generations. The change in climate and the possible effects on the Cognac grapes, soil, and even aging methods poses a formidable challenge to the next generation of producers.

20. Environmental Problem Type: Culture

21.

Name, Type, and Diversity of Species

Name: Ugni Blanc, Folle Blanche, Colombard

Type: White

Diversity: Low

22. Resource Impact and Effect: High and Product

23. Urgency and Lifetime: Low and 100s of Years

24. Substitutes: Like Products

25. Culture: Yes

26. Trans-Boundary Issues: No

27. Rights: No

28. Relevant Literature

1. Article 23 of the Agreement of Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS) of the World Trade Organization (WTO). http://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/27-trips_04b_e.htm

2. “Climate Change in the Vineyards: The Taste of Global Warming.” California Wine and Food Magazine (Nov 2003). http://www.californiawineandfood.com/wine/climate-change.htm

3. Bradford, Robert. “Cognac.” Beverage Business Online. January, 2004. http://www.beveragebusiness.com/art-arch/bradfordl0104.html

4. Chery, Carl. “Daily Hip-Hop News: Hip-Hop Saves the Cognac Liquor Industry.” July 18, 2003. http://www.sohh.com/thewire/read.php?contentID=4858

5. European Commission. “TBR Proceedings Concerning Brazilian Practices Affecting Trade in Cognac.” Brussels, 18 Dec.1997.

6. European Commission. “Trade Barriers Regulation: The First Five Years.” http://www.mcx.es/sgcomex/Polaran/documentos/first5years.PDF

7. European Commission. “WTO talks: EU steps up bid for better protection of regional quality products.” IP/03/1178. Brussels, 28 Aug. 2003.

8. European Commission: “Intellectual Property: Why Geographical Indications matter to us?” Brussels, 30 July 2003. http://europa.eu.int/comm/trade/issues/sectoral/intell_property/argu_en.htm

9. European Commission:

“Trade Barriers Regulation: What is TBR?” Brussels, Sept.

2003.

http://europa.eu.int/comm/trade/issues/respectrules/tbr/index_en.htm

10. Graafsma, Folkert, and Sofia Alves. “International Trade Developments, Including Commercial Defence Actions XIII: 1 January 1997 – 31 June 1997.” http://www.ejil.org/journal/Vol9/No2/sr1.rtf

11. Gugino, Sam.

“Cognac: Though Purists May Shudder, France's Premier Brandy Mixes

with the Cocktail Crowd.” The Cigar Aficionado Online. (Sept/Oct

1998)

http://www.cigaraficionado.com/Cigar/CA_Features/CA_Feature_Basic_Template_Print/0%2C2809%2C723%2C00.html

12. Kummer, Corby.

“Don’t call it Cognac.” The Atlantic Monthly. (Dec

1995) 276.6: 125-128.

http://www.theatlantic.com/issues/95dec/cognac/cognac.htm

13. Lienhard, John

H. “Engines of Our Ingenuity: No. 1824 Texas Cognac.” From

West, R. “Root de France.” Kentucky Alumnus. (1988) 4: 14-16.

http://www.uh.edu/engines/epi1824.htm

*All statistical data was taken from the Bureau National de

Interprofessionnel de Cognac (BNIC) website at http://www.bnic.fr

*

WEBSITES and GENERAL INFORMATION

http://www.cognac-co.com/Learn.htm

http://www.guerbe.fr/eng/index2.htm

*

*photo courtesy