I.

Identification

I.

Identification

| TED

Case Studies, 2003 |

JACK AND THE ENOLA BEAN By, Danielle Goldberg |

I.

Identification

I.

Identification1. The Issue

The Enola Bean is an alleged case

of biopiracy, where Larry Procter, a Colorado executive in the bean industry

cultivated yellow beans he bought in Mexico on vacation for which he received

a US patent two years later on all yellow beans of this variety. Larry’s

company, Pod-Ners, admits that its Enola bean, (named after Larry Proctor’s

wife), is a descendant of the traditional Mexican bean from the Andes, the Mayacoba,

but that it has a better  yellow

color and a more consistent shape. By obtaining a patent and a U.S. Plant Variety

Protection Certificate, he secured what amounted to a legal monopoly over yellow

beans sold in the United States. Under the terms of the patent, he can therefore

sue anyone in the United States who sells or grows a bean that he considered

to be his particular shade of yellow. Procter also profits from yellow beans

imported from Mexico by imposing on them a six cent-per-pound royalty. As a

result, both farmers in the United States and particularly in Northern Mexico

have suffered great economic hardship. The case has stimulated great debate

over whether traditional knowledge and/or genetic resources should be patentable

in the first place. As the number of patents filed by large corporations for

native crops increases, activists become more concerned about the adverse effects

of these patents on developing countries and particularly indigenous people.

yellow

color and a more consistent shape. By obtaining a patent and a U.S. Plant Variety

Protection Certificate, he secured what amounted to a legal monopoly over yellow

beans sold in the United States. Under the terms of the patent, he can therefore

sue anyone in the United States who sells or grows a bean that he considered

to be his particular shade of yellow. Procter also profits from yellow beans

imported from Mexico by imposing on them a six cent-per-pound royalty. As a

result, both farmers in the United States and particularly in Northern Mexico

have suffered great economic hardship. The case has stimulated great debate

over whether traditional knowledge and/or genetic resources should be patentable

in the first place. As the number of patents filed by large corporations for

native crops increases, activists become more concerned about the adverse effects

of these patents on developing countries and particularly indigenous people.

2. Description

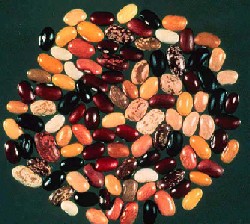

Larry Proctor, the president of a Colorado (USA) based seed company, POD-NERS, purchased a bag of dry multi-colored beans in Mexico in 1994. Noticing the novelty of the particular yellow beans among them, Proctor planted the yellow beans in Colorado and left them to self-pollinate. He followed a process of segregating the yellow beans in several generations, creating a population in which the color of the bean entire seed coat remained uniform and stable season after season, when viewed in natural lighting. Proctor's company now owned the US patent for any beans falling within a range of yellow on the color spectrum.

Two years later, he filed for an exclusive monopoly patent. Proctor won a US

patent. 5,894,079

- also known as the yellow bean or "Enola bean"- at the US Patent

& Trademark Office in Washington, D.C, in April 1999. ‘I think that

when Larry started his work, he may not have known what a patent was,’

said David Lee, a lawyer in Boulder, Colorado who specializes in patent lawsuits.

He says that in 1996, another attorney helped Mr. Proctor apply for a patent

on his yellow bean by documenting why he believes his invention that is, his

seed, is better than previously known varieties of yellow beans (Shlender, 2002).

According to Procter’s US patent application filed November 15, 1996:

“This invention relates to a new field bean variety that produces distinctly

colored yellow seed which remain relatively unchanged by season.” Included

within the application is a description of this “distinct” color,

including the “hue,” “value,” and “chromo,”

according to the color notation system of the Munsell Book of Color. To be patentable,

an invention must also be replicable by someone else "skilled in the art".

In other words, an invention must be well enough described in a patent claim

that someone else in the same field could reproduce it from the description.

Thus, the application further claims patent rights to the method for producing

the field bean plant, which involves “crossing a first parent field bean

plant with a second parent field bean plant, wherein the first and/or second

field bean plant is the field bean plant of the present invention.” Therefore,

any method using the cultivar Enola is part of this invention.

Immediately after obtaining the patent, Procter sent a letter to all importers

of Mexican beans warning that this bean was his company’s property, and

anyone that planned to sell it would have to pay royalties to Pod-ners. Soon

after, Larry Proctor filed lawsuits on 30 November 2001 against 16 small bean

seed companies and farmers in Colorado that were selling Mexican yellow beans

in the US, claiming that they were violating the patent by illegally growing

and selling his yellow "Enola" bean. In addition, export sales immediately

dropped over 90% among importers that had been selling these beans for years,

causing economic damage to more than 22,000 farmers in northern Mexico who depended

on sales of this bean. Generic fear over the sale of beans extended beyond the

yellow bean variety and affected the entire bean industry (Locke, 2001).

There have been a variety of responses to Pod-Ners controversial US patent on

the yellow-colored bean variety among Mexican consumers, Mexican bean exporters,

small bean seed companies and farmers in the United States. A lawsuit was filed

on behalf of the Mexican farmers in protest, responding to the 90% drop among

exporters selling these beans, which caused economic damage to more than 22,000

farmers in northern Mexico who depended on these sales. Customs officials at

the US-Mexico border are now even inspecting beans, searching for any patent

infringing beans being imported into the United States. As a result, generic

fear over the sale of beans extended beyond just the yellow bean variety to

affect the entire bean industry, causing some small growers in the United States

to give up and sell their land to agribusiness.

THE MEXICAN DRY BEAN INDUSTRY (Go

to Top)

The Mexican Dry Bean Industry is

already has faced substantial challenges in competing within a global free market.

While macroeconomic indicators following the NAFTA agreement signaled success

in terms of agricultural economic activities, commodity prices, especially for

crops traditionally grown by campesinos, have dropped significantly. For example,

between 1993 and 1998, the price of beans have fallen 51%, indicating a decrease

in Mexico’s food security and an increased dependency on the U.S. for

food (SIPAZ, 2001).

The Enola bean case seems to put salt on the wounds of Mexican accusations that

American bean producers are emptying beans into the Mexican Market, depriving

domestic markets of business. Mexico claims that the U.S. is dumping beans into

Mexico by buying beans from other countries and reselling them in Mexico, so

that Mexico cannot compete. Mexico has used such claims to justify resisting

compliance with NAFTA Trade quotas for bean imports, a protected commodity for

Mexico under NAFTA.

While NAFTA arranged agreements to aid Mexican farmers in the transition form

fixed prices to a competitive market over 15 years, Mexican farmers have often

been upset over the entry of high quality bean imports displacing their product

in domestic markets (Pratt, 2003). International bean competition is difficult

for Mexican bean growers, as for, unlike other bean producing countries, Mexico

lacks irrigation for most dry bean acreage in Mexico, making the crops susceptible

to drought. During terms of drought-related shortfall in production, such as

in early 1998, the Mexican government had to authorize auctions of duty-free

import permits to meet dry bean demand (Statpub 2000). According to United States

FAO Statistics in 2001, Mexico was the fourth largest importer of dry beans.

While the United States was the second largest importer, it happens to be the

second largest exporter of beans, with 90% of the Mexican import share (Statpub

July 2003) (See Table A… to be inserted). Accusations of fowl play go

both ways within the bilateral trade agreements between Mexico and the United

States. While Mexico accuses the United States of “dumping,” the

United States has accused Mexico of attempting to break the NAFTA agreement

by blocking dry bans from their markets using the justification of stricter

and unprecedented pytosanitary standards (Michigan AgriWeekly, 2003). The Enola

Case only further intensifies both interstate and bean industry conflict over

free trade.

SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT

It seems that not all Mexican farmers are aware of new patenting laws infringing

on their market, and the full extent of their implications. One 65 year old

Mexican farm worker from Chihuahua, Jesús Villalobos was stunned and

upset when told about the restrictions on exports of the yellow beans to the

U.S., calling Pod-ners, a “bandito,” among other things. Like many

other Mexicans, Villalobos grew up eating these beans (Dechant, 2001). In fact,

beans are a staple in the Mexican diet. Ninety-eight percent of surveyed Mexicans

in the Northwest region of Mexico eat the yellow bean, known as “Azufrado,”

or “Mayacoba.” Years ago archaeologists discovered yellow beans

in a cave in the Peruvian Andes and dated them back at least four millennia

to before the Incas. Thousands of years later, Mexican agronomists crossed two

yellow-tinted varieties and came up with a modern version of the yellow bean.

This was back in 1978. They called it Mayacoba after a nearby village in Sinalou

state. Mayacobas have been coming out of this valley, thousands of tons worth,

ever since (Weekend Edition, 2001).

Much over the controversy has been over the alleged difference between the Enola

and the traditional Mayacoba bean. Proctor insists that the traditional Mayacoba

beans are “different” from his Enola beans, planted on Colorado

soil. In response, when asked why importers of Mayacoba beans could then be

infringing on his patent, he accused Mexican migrants of possibly “stealing”

his Enola beans right from his fields (Weekend Edition, 2001). Yet, as far as

warehouses in LA and Chicago are concerned, the beans are interchangeable. One

bean trade in Denver even said that he slaps a Maycoba label on every bag of

Enolas he gets so consumers know what they’re getting. Despite all legal

claims to the bean, many still believe that this niche in the America’s

Latino market was actually created with the initiative of Rebecca Gilliland,

the would-be bean trader in Nogales (Weekend Edition, 2001).

The yellow bean market already had a large Mexican consumer based before Procter

took control, with a significant 98% of Mexicans surveyed in Northwest region

claiming to eat yellow beans. In the early '90s, Gilliland retired as a small

oil producer in California and came to Arizona to take advantage of the onset

of NAFTA. “‘In 1994 I was missing, here in the United States, the

beans they've been eating in Mexico,’” says Gilliland, “‘the

one I grew up with, the peruano Mayacoba. It's very, very delicious. Once you

eat this bean, you never eat the pinto again. The taste is so unique.’”

Gilliland considered the possible Mexican-American market for the bean and soon

teamed with some colleagues in Los Mochis to slowly began selling the beans

to distributors and grocery chains. Stores weren’t interested at first,

until they recognized the growing consumer demand. Within a year, her imports

of the yellow beans tripled. That is, until Larry Proctor proudly announced

that he had invented the yellow bean and that it was illegal to bring that bean

from Mexico. This yellow bean presented a new way to expand his crop base, which,

according to dry bean industry trends, has been susceptible to commodity increases

and price crashes year after year.

When talking about the yellow bean patent, one bean farmer commented that “‘In

the beginning I thought it was a joke. They asked me when I started selling

the beans. And I told the guy, ‘Way before you invent it. These beans

[are] from Mexico, and these beans are being legally declared through the customs.

We're not smuggling anything.’ And I say it's very surprised that you

just invent it when I've been eating it for 30 years, you know?’”

(Minnesota Public Radio, 2001).

While many consumers and some Mexican farmers are unaware of the case, most

affected companies in the United States, however, have been extremely aware

and proactive about the issue, particularly in Colorado. Responding to the lawsuits

Larry Procter filed in November 2001 against 16 small bean seed companies and

farmers in Colorado, Bob Brunner, President of Northern Feed & Bean, stated

‘We were shocked to be accused of infringing Proctor's intellectual property’

(ETC, Dec. 2001). Pod-Ners lawsuits accused growers and processors of violating

the patent by secretly growing Enola beans and calling them Mayacoba. Yet Brunner

claimed, ‘We've been growing yellow beans from Mexico since 1997 - and

they are not Proctor's Enola beans.’

This is a contemporary story of genes and economics. Mexico's National Research

Institute for Agriculture, Forestry and Livestock (INIFAP) recently conducted

a DNA analysis of POD-NERS' patented bean. The results indicate that the Enola

variety is genetically identical to Mexico's "Azufrado" bean. That

said, one may ask, is color enough uniqueness to grant a patent when it has

never been grown in the United States? The International Center for Tropical

Agriculture, CIAT, and Action Group

on Erosion, Information and Technology, ETC,

(Formerly RAFI), of Canada consider this injustice. They both filed a formal

request to reexamine the patent for a possible violation of the 1994 FAO Trust

agreement that requires the designation of germplasm as public domain and off-limits

to intellectual property claim. In 2000, RAFI also denounced the yellow bean

patent as "Mexican bean biopiracy" and demanded that the patent be

legally challenged and revoked.

Of particular concern is the patent’s claim of exclusive monopoly on any

Phaseolus vulgaris (dry bean) with a seed color of a particular shade of yellow.

The CIAT claims that this patent “will make a mockery of the patent system

to allow statutory protection of a color per se." While Proctor did not

obtain his yellow beans from among CIAT’S gene research bank of more than

27,000 dry bean samples, CIAT claims to maintain some 260 samples of beans with

yellow seeds. Six of these are nearly identical to the Enola patent. From CIAT’s

point of view, this yellow bean was “Misappropriated” from Mexico,

violating Mexico’s sovereign rights over its own genetic resources, thus

violating the Convention on Biological Diversity. Mexico says genetic fingerprinting

shows that the Enola bean is the same as a bean registered in Sinaloa, Mexico,

in 1978 scientific evidence that Andean peasant farmers developed this bean

first, along with Mexico.

Northern Feed and Bean Co., of Lucerne Colorado, and sister company Yellow River,

maintained that their yellow bean seeds were Mayacobas that come from Sinaloa,

Mexico (ETC, Dec. 2001). Over 100 farmers sell pintos and other beans in Lucerne,

Colorado, including yellow beans that Northern Feed says he bought directly

from growers who developed them in Mexico. According to Bob Brunner, owner of

Northern Feed and Bean, ‘We had experimented with these yellow beans before

Proctor had his patents. I refused to be a licensee, because I didn't think

it was necessary for us to pay a license fee’ (Fujii, 2002). . "They

were not Enola," said Bob Brunner. "They were Myocobas that we brought

in from Mexico." This is a lie, according to Proctor, who is suing Mr.

Brunner, along with other U.S. farmers and importers for allegedly secretly

planting his Enolas. Mr. Brunner denies the allegations..

In addition, Brunner, notes an unjustified rise in costs for the whole industry

over the patent. While he would contracted with Greeley area farmers to produce

yellow beans for $40 per cwt (hundred pounds), a few Delta area farmers who

contacted Brunner complained that Pod-ners contracted with them for only $25

per cwt (Dechant 2001). Despite all this, ultimately, under legal and financial

pressures, Brunner and other opposing companies agreed to pay undisclosed financial

compensation for allegedly selling the bean variety to at least a dozen northern

Colorado farmers without Pod-ner’s permission.

According to Larry Procter’s lawyer, "There's a lot of talk about

Mr. Proctor doing nothing, but he devoted five years to coming up with what

is basically a new bean" (Hansen). Not all bean growers, however, have

opposed the patent. According to grower Teixeira, controlled production under

the patent will assure a decent profit from year to year. Likewise, he believes

that the consumer gets a steady supply of quality product, at a fair price.

“’The non-patented beans have been around for years, but ‘there's

never been that much action on them.’ said Teixeira. Initially, most of

the beans sales took place in Mexico, but demand for the yellow beans have risen

in the last few years” (Hansen, 2001). "The consumer out there likes

what we're doin'," said Procter. "They're buying it. Our farmers are

makin' money on it, where they were goin' broke on other crops or living off

the government subsidies" (Shlender, 2002). Procter said he’s been

doubling and tripling his production each year and failing to keep up. This

comes in contrast to the continual commodity surpluses and price crashes Teixeira

has seen in his 30 years in the bean industry (Fujii, 2002).

3. Related Cases

Maca: Dispute between US and Peru over patent rights on the extractions from a traditional medicinal plant

Grappa: Dispute between South Africa

and the European Union over the alcoholic beverage Grappa

Aidsstrips: Intellectual Property Rigths and the AIDS drug in South Africa

Basmati: Dispute over the rights to name “Basmati”

Canola: Dispute between Saskatchewan

famers and Monsanto Company over the rights to grow canola

Kimchi: Dispute between South Korea

and Japan on the rights to product Kimchi

Neemtree: Dispute between the US

and India over rights to products from the Neem tree

Scotch: Scotland’s intellectual

property rights to the alcoholic beverage

Tequila: Mexico’s demand that

tequila be protected as a “geographically indicated product” under

intellectual property law

4. Author and Date:

Danielle B. Goldberg

December 2003

II.

Legal Clusters (Go

to Top)

II.

Legal Clusters (Go

to Top)5. Discourse and Status:

Patents were originally created more than 500 years ago to help industrial inventors protect their inventors, and to stimulate innovation. While this appears honorable in theory, in today’s world of corporate power, big business can manipulate patent legislation to attain monopoly, far from the original intention of encouraging creativity.

Worldwide criteria require patents to demonstrate novelty, utility, and inventiveness.

Thus, discoveries are not patentable, but something that can be replicated by

someone in the same field. This criteria assumes that life forms and traditional

knowledge are eligible for patents. Since 1980, the patent system has slowly

expanded to include patents on living and genetically modified organisms. In

particularly, bioprospecting, or the search for genetic material of market value,

has become one of the most rapidly developing industries of the 21st century.

International patent laws within the broader sphere of intellectual property

rights, determine the extent to which “biopiracy can be controlled.”

While the World Trade Organization has frequently discussed the issues of indigenous

rights and the patenting of life forms, particular guidelines to the phenomenon

are unclear. Thus, those regions in the world with the greatest biodiversity,

such as Mexico, are sometimes seen as a playground for large pharmaceutical

and food companies and potential cases of “biopiracy.” Poor farmers

in Mexico and around the world now face the threat of having to pay licensing

fees to grow indigenous crops grown in the region for generates to large biotechnology

and seed companies with the resources to patent these products.

Both developing countries and civil society groups are trying to take both legal

and advocacy recourse in thwarting alleged cases of biopiracy. In the case of

the Enola Bean, the International Center for Tropical Agriculture, for example,

made the claim in December 2000 that the yellow bean was ‘misappropriated’

from Mexico, and that it violates Mexico’s sovereign rights over its genetic

resources, as recognized by the Convention on Biological Diversity. Following

intense cries of biopiracy among civil society groups and the Mexican government

against Larry Proctor’s yellow bean patent, Procter contested a reexamination

of the Enola bean patent sought by the International Center for Tropical Agriculture

in December 2000. While his lawyers have ardently defended his claim to the

Enola Bean, the US Patent and Trade Office have been forced to re-examine proceedings

with the re-issue proceedings, thus complicated and delaying a final decision

(ETC, Dec. 2001).

It is uncertain whether CIAT’s challenge will eventually be successful,

as strong arguments lie on both sides. Yet, irregardless of the result of the

Enola Bean patent challenge, the issue of biopiracy and protection of traditional

knowledge is far from over within the legal international arena. Increased biotechnology

and global competition among corporations for patents over the monopoly of seeds,

crops, and genetic plant resources have resulted in greater cases of alleged

biopiracy, intensifying international controversies on the establishment of

legal international guidelines on intellectual property rights of plant and

genetic materials.

6. Forum and Scope:

The World Trade Organization (WTO), led by support of the United States, created an institution to set guidelines for these issues through Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), a precedent-setting agreement created by governments at the GATT Uruguay round. TRIPS permit individuals and corporations to claim exclusive rights over genes, life forms, microorganisms, and micro-processes by which they perform their functions. Developing countries were initially reluctant to accept the agreement, despite pressure from U.S. and Europe, as they saw it as a threat to sustainable development in their own terms. Most controversial were the provisions about patents on life forms in Article 27.3(b), which were supported under the provision that they would be reviewed before they were fully implemented in developing countries in 2000. (This agreement allows Procter to even patent his bean variety in the first place.) This review has moved extremely slow, given North-South disagreement over the increasing pressure within global movements to prevent the occurrence of biopiracy and enacting greater checks and balances within WTO provisions. Still, given the subordinate position of most developing countries in formulating international law, there is the risk that reforms will only further expand intellectual property rights on life. This would further protect the right of such corporations as Pod-ners to patent life resources while further harming communities who rely on biodiversity and traditional knowledge for their livelihood.

For many critics, it is not a question of clauses being present of absent, but

a question of the fundamental assumptions about the appropriateness of applying

patent or patent-like legislation to life forms or to traditional knowledge,

which are essentially public, 'non-divisible' goods, and not seen as 'property.'

A 1999 statement on TRIPS released by a global network of indigenous people's

organizations, and NGOs made this assertion: Knowledge and cultural heritage

are collectively evolved through generations. Thus no single person can claim

inventions or discovery of medicinal plants, seed or other living things. The

inherent conflict between these two knowledge systems ... will cause further

disintegration of our communal values and practices." African governments

and the Organization of African Unity have taken similar positions on life form

patenting as being unethical and alien to the cultural beliefs of Africans (Sveenivasan,

2001).

According to Article 27.1 of the Trips Agreement, Member countries are required

to make patents available for any inventions, whether products or processes,

in all field of technology without discrimination, subject to the normal test

of novelty, inventiveness and industrial applicability. It also requires that

patent and patent rights be available without discrimination as to the place

of invention and whether products are imported or locally produced (WTO Trips).

The question of novelty, however, becomes suspect when patent applicants are

not legally required to disclose from where they obtained the genetic material.

Larry Procter admitted that the obtained the original beans from Mexico; however,

there is currently no agreement among governments regarding a requirement to

disclose information. In that case, a patent office can not determine whether

an invention actually occurred, or whether someone is in a sense, misappropriating

ownership of a region’s traditional natural resources, or ‘biopiracy.’

Thus, while the Enola Bean patent is among the most resent controversial case

over the patenting of genetic plant resources derived from developing country’s

resources, this case is not unique. In 1998, RAFI and the Heritage Seed Curators

Australia, HSCA,

released a report documenting 147 examples of plant breeders rights were allegedly

collected plant varieties collected in foreign countries without any evidence

of breeding.

Following thee increasing incidents of biopirated materials or knowledge, developing

countries have been pushing hard to include this rule on disclosure of origin

in TRIPS. Currently, the only resource available is to challenge the patent

in the courts or before the patent office in the country where the patent was

issues, such as in the Enola Case. Such an investigation is expensive, slow-moving,

and easily thwarted by counter legal action. Furthermore, many of the communities

affected by such patents do not have the resources to follow legal recourse.

A recent proposal by the Africa group however, would require patent applicants

to declare the origin of their invention, and in the case of indigenous knowledge,

acquire consent from local communities offering the resources, and a measure

of benefit sharing. Africa rejected a new proposal to bring traditional knowledge

(TK) formally within the prescriptions of TRIPS, instead pushing for an additional

TRIPS section to specify under what conditions traditional knowledge can be

placed under International Property Rights, and how they should be protected.

The Africa Group asserted than any regime for plant varieties should protect

the rights of Farmer and local communities. On the opposite spectrum, The United

State, opposed to singing any such agreement, reject any attempt to exclude

any kind of inventions from patenting, including plants and animals.

Most recently, certain industrialized countries, particularly the European Union

an Switzerland, have shown some interest in negotiating a mechanism to disclose

the origin of genetic materials or traditional knowledge used in patented inventions.

If TRIPS forced patent applicants to disclose the origin of genetic resources,

it would be easier to determine the validity of the patent. Neither Europe nor

Switzerland, however agrees to make this mandatory, to include an element of

benefit sharing for these patents, nor to require the attainment of consent

among affected indigenous communities. Furthermore, they both maintain a vague

definition of an invention’s origin, referring to merely a ‘geographical

area’ or ‘source (GRAIN, 2003).

Analysis of individual cases is complicated by the fact that to all international

agreements are consistent with TRIPS polices. The food and Agricultural Organization’s

(FAO), International Undertaking on Plant Genetic Resources, for example, follows

the UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity, maintaining that plant genetic

resources are pat of humanity’s common heritage and belong within the

public domain. However, these organizations have no enforcement mechanisms,

unlike the WTO. As a result, WTO policies demonstrate the discourse over private

versus public control of plant and agricultural genetic resources.

Furthermore, most of the legal framework to protect TK under the WTO is fraught

with contradictions and controversy, as the WTO, with its narrow concerns for

increased international trade, is seen more as the problem than the solution.

Even measure to protect traditional knowledge by patent origin identification

and benefit sharing contradicts community values that view this information

as cultural, spiritual, and outside the realms of patent. Still, developing

countries continue to demand that TRIPS apply broader exception on the obligations

of developing countries to adopt full fledge IDR regimes by considering cultural

and social welfare needs of the country. For example agriculture is the primary

source of employment and livelihood for 3 out of 4 people in poor countries,

which includes Mexico (Rattray, 2002). Patenting can greatly affect the livelihood

of these farmers? With the Enola Bean patent, some Farmers may be unable to

grow the crops they have grown for generations without first paying royalties

to PODS-NERS.

Furthermore, if activists were legally successful in claiming that Enola Beans

were no different than Maycaoba beans, for example, perhaps these beans would

be protected as a geographic indicator, given its historic connection to Aztec

cultivation of these particular beans in the Andes. At this point, however,

as biodiversity and traditional knowledge are not excluded from RIPS, the power

of advocacy remains on civil society groups to educate the international community

on the moral and legal illegitimacy of legal patents on allegedly biopirated

life materials. Organizations such as CIAT and RAFI, as well as active Indigenous

and Mexican Farmer groups may be able to influence the importance of the Enola

Bean review, and other such cases, by directed public opinion in favor of indigenous

rights and sustainable agricultural markets.

7. Decision Breadth:

The United States and Mexico with overarching implications from World Trade Agreements

8. Legal Standing:

Disagreement and in process

It has been almost one year since CIAT filed its request for re-examination

of the Enola bean patent. The PTO's decision has been stalled because Larry

Proctor's lawyers have amended the original patent by filing 43 new claims.

The PTO responded by merging the re-examination proceedings with the re-issue

proceedings, thus complicating and delaying a final decision (ETC, Dec. 2001).

Procter contests the reexamination of the Enola bean patent sought by the International

Center for Tropical Agriculture, and in 2001, he filed additional suits against

a group of Colorado farmers and bean processors for producing yellow beans.

III.

Geographic Clusters

III.

Geographic Clusters9. Geographic Locations

a. Geographic Domain: North America

b. Geographic Site: Southern North America

c. Geographic Impact: Mexico and the United States

10. Sub-National Factors:

11. Type of Habitat:

IV.

Trade Clusters (Go to Top)

IV.

Trade Clusters (Go to Top)12. Type of Measure: Intellectual Property

13. Direct v. Indirect Impacts:

Of fundamental importance is the fact that monopoly control of agricultural genetic resources involves essential ethical and practical questions about food security, development, social and economic justice, community and farmers' rights, environment and biodiversity. These questions revolve around the principle of public versus private control of humanity's basic life-support systems - seeds, food crops, air and water.

14. Relation of Trade Measure to Environmental Impact

a. Directly Related to Product: Yes- Enola Bean

b. Indirectly Related to Product: No

c. Not Related to Product: No

d. Related to Process: No

15. Trade Product Identification: faded yellow bean

16. Economic Data

17. Impact of Trade Restriction: Medium

18. Industry Sector: Agricultural

19. Exporters and Importers: United States and Mexico

V.

Environment Clusters

V.

Environment Clusters20. Environmental Problem Type:

21. Name, Type, and Diversity of Species

Name: Dry beans

Type: Phaseolus vulgaris

Diversity:

22. Resource Impact and Effect: Low and Regulatory

23. Urgency and Lifetime: Low and Annual

24. Substitutes: Pinto bean, Mayacoba bean, Azufrado bean

VI.

Other Factors

VI.

Other Factors25. Culture:

For many farmers in Mexican, monopoly control of agricultural genetic is an issue that goes beyond just economic losses. It is a moral injustice to misappropriate the genetic resources of land that have long existed within a society’s economy and culture. Activist groups like the ETC warn that the Enola case "demonstrates very clearly how monopoly patents can threaten food security and the livelihoods of farmers," said Hope Shands. Ms. Shands says that from the standpoint of the world's food supply, Ms. Shands says that seed patents stop farmers from saving and swapping seeds, making it illegal to do so without paying license fees to the patent owner. This could therefore endanger seed diversity. (Shlender, 2002). Mexico culture in particular place a large importance on beans and seed sharing, while patenting laws contradicts the communal sharing of these natural resources.

Plants have historically been a large part of Mexican culture and are tied together

with many issues. In the past maize was part of creation myths and played a

major role in the development of prehispanic cultures. Plants imported to Mexico

such as sugar cane had far reaching impacts on land use, labor and class systems.

Crops such as tomatoes, peppers and maize were exported and have dramatically

changed food diets around the world. In other regions, seeds still held a strong

place in culture. In Tepoztlan, Morales on an arch heading into the courtyard

of the town Cathedral there is a beautiful mural of hills, people and life,

made entirely from seeds created by the community. Seeds, as these examples

suggest, are viewed not so much as means of production or a means of profit

but much more holistically, as a part of life and food and culture (Hough).

Agricultural plants in the South, developed by farmers over thousands of years,

have been bred and adapted to suit local conditions. For example, of the hundreds

varieties of corn grown in Mexico, each has unique characteristics and features:

some more adaptable to frost or drought, other grow in higher altitudes, some

produce late in the season, others early. The free exchange of this knowledge,

as well as local sale and exchange of seeds, has been an essential aspect of

food security among the poor. In the developing word, only 10 per cent of seed

is bought commercially, and many poor farmers buy seed only every five years

(Sreenivasan, 2001).

Dr. JOACHIM VOSS (Director, Center for International Tropical Agriculture) stated,

“I've worked with farmers in Asia, Africa, Latin America. Universally,

those farmers freely exchange varieties between themselves as a form of reciprocal

seed exchange. And they're delighted when somebody else recognizes the value

of the varieties that they are using. For them, the idea that you might put

proprietary claim on a variety just seems like it's coming from the moon. I

mean, it's just totally outside of their realm of social values” (Weekend

Edition).

One Zapatista community is trying to counteract threats against traditional communal agricultural practices by teaching the importance of seed sharing in schools. One education promoter in this program explained:

We must make the effort to save the

seeds which grow in our communities because a new type of seed known as transgenetic

is arriving and this seed could destroy the plants which our ancestors created

over thousands of years. These seeds are specially adapted for our climates

and soils and must never be lost! In our language which is Tzotzil we call our

new project "Sme’ Ts’unubil ta Ts’ikel Vokol ta Jlumaltik,

Chiapan" which means Mother Seeds in Resistance from the Lands of Chiapas

(Chiapaslink, Feb. 2002).

26. Trans-Boundary Issues:

Patents on life forms, Indigenous rights to biological resources and knowledge, International Patent legislation.

27. Rights: Rights to indigenous knowledge and protection of regional life resources

28. Relevant Literature

Chiapaslink, (2002, February).

Dechant, David. “Bean Biopiracy in Colorado.” (2001, Dec. 21). http://www.cropchoice.com/leadstry.asp?RecID=544.

Delgado, Gian Carlo. Biopiracy and Intellectual Property as the Basis for Biotechnological

Development: The Case of Mexico. (2002). International Journal of Politics,

Culture, and Society. 16, no. 2.

Enola Bean Patent Challenge. (2001,

January 5). Rural Advancement Foundation

International. Available at www.rafi.org.

FASonline. (1998). NAFTA Helps Expand

Mexican Grain Markets for U.S. Farmers.

www.fas.usda.gov/grain/circular/1998/98-09/dtricks.htm.

Fujii, Reed. (2002, Sept. 15). “U.S.

Dry Bean Production Business Gets Ugly.” Knight

Ridder/Tribune Business News.

GRAIN. (2003, July). “The

Trips Review at a Turning Point?” http://www.grain.org/front/index.cfm.

Hough, Andrew. Trip Report for Mexico

Biotechnology and Food Security. http://www.mennonitecc.ca/us/globalization/hough/mexico.html.

Intellectual property law, genetic resources and GMOs: on the agenda at FAO.

(2002, October 28). http://www.fao.org/english/newsroom/news/2002/10300-en.html.

Locke, Christopher. (2001, March

15). Has Bioprospecting Gone Wild? International

rights groups are working to protect indigenous peoples and their precious

pharmaceutical resources. http://www.redherring.com/mag/issue95/250018225.html.

McGrath, Peter. Biopiracy threat to traditional crops. New Agriculturist Online. http://www.new-agri.co.uk/02-5/develop/dev03.html

Mexican Bean Conspiracy. (2002 Spring).

US-Mexico Legal Battle Erupts over

Patented “Enola” Bean. RAFI release. http://www.greens.org/s-r/22/22-21.html.

Michigan AgriWeekly, (2003).

Minnesota Public Radio. (2001). Martin

Robles and the Mayacoba.

http://www.americanradioworks.org/features/food_politics/beans/3.html.

Mutume, Gumisai. (2000, Jan. 28).

Developing World Fights for Control over Genetic

resources. Mexico City (IPS World Desk).

ttp://www.oneworld.org/ips2/feb00/18_26_077.html.

Pratt, Sean. (2003, Oct. 15). “Mexico Ripe for Bean Sales.” Saskatoon Newsroom.

Pratt, Timothy. (2001). Small Yellow

Bean Sets off International Patent Dispute. New

York Times. Found in: http://www.loka.org/_news1/00000002.htm.

Pringle, Peter. (2003). Food, Inc:

Mendel to Monsanto-The Promises and Perils of the

Biotech Harvest Simon & Schuster.

Proctor's Gamble. ( 2001, December

17). ETC group, www.etcgroup.org, News

Release. http://www.gene.ch/genet/2001/Dec/msg00065.html.

Rattray, Gillian A. (2003) “The

Enola Bean Patent Controversy: Biopiracy, Novelty and

Fish-and-Chips. Duke L. & Tech. Rev. 0008.

Shlendler

Simon, Scott, (broadcast host). Profile: Controversy over Patent Held by One American Farmer for a Yellow Bean with Origins to the Incas. Weekend Edition. Saturday. Washington, D.C.: Jun 9, 2001. pg. 1.

SIPAZ Internal Document. (2001).

Presentation: Economic Issues. San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas.

Sreenivasan, Gauri & Jean Christie.

(2002 March). Intellectual Property, Biodiversity, and the Rights of the Poor.

Canadian Council for International Co-operation Trade and Poverty Series. http://www.gefoodalert.org/library/admin/uploadedfiles/Intellectual_Property_Biodiversity_and_the_Rig.htm.

Statpub. (2003 July). US Edible Bean

Consumption Flattening. http://www.statpub.com/stat/open.2003.7/56123.

United States Enola Bean Patent Application. http://patft.uspto.gov/netacgi/nph-Parser?Sect1=PTO2&Sect2=HITOFF&u=/netahtml/search-adv.htm&r=1&p=1&f=G&l=50&d=ptxt&S1=5,894,079&OS=5,894,079&RS=5,894,079.

Weekend Edition, 2001.

WTO Trips. http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/eol/e/wto07_23.htm#note8.