|

Number 677, 2003 by Elizabeth Jahncke |

|

Identification

Legal Cluster Bio-Geographic Cluster Trade Cluster Environment Cluster Other Clusters |

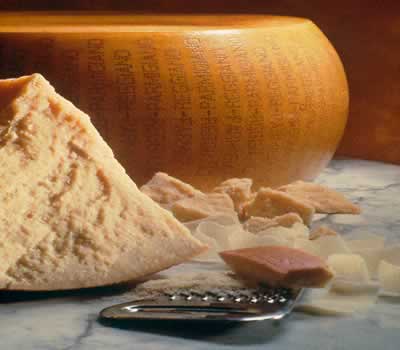

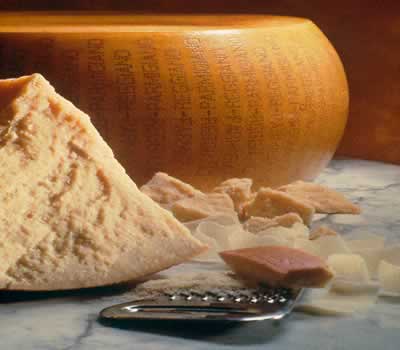

1. The Issue

For many Americans, Parmesan cheese, as we know it, comes in a green, cylindrical can. Manufactured by large cheese companies, most American Parmesan cheese is mass-produced and sold in grocery stores everywhere at a competitive, but low price, ensuring that spaghetti and meatballs throughout the United States are garnished with its unmistakably unique flavor. However, for many Italians, Parmesan cheese is not mass-produced by large, Italian cheese companies. Ask an Italian how Parmesan cheese is made and they may answer, Non si fabrica, Si fa - It is not made, but rather, produced.

2. Description

A History of Cheese

Truth is, we take cheese for granted. Many of us know the origins of coffee or even chocolate, but how many of us know the origins of cheese? Legend has it that cheese was discovered by, "an unknown Arab nomad". The story goes that in preparation for his journey this nomad filled his saddlebag with milk in order to provide him with sustenance for the long journey across the desert. After several hours, he stopped to drink from his saddlebag only to find that the milk had separated into a pale, watery liquid with medium-sized, solid, white lumps. The desert nomad found the mixture both drinkable and edible. What the nomad did not know was, "because the saddlebag, which was made from the stomach of a young animal, contained a coagulating enzyme known as rennin, the milk had been effectively separated into curds and whey (by the combination of the rennin, the hot sun and the galloping motions of the horse". As thus, cheese (perhaps not as we know it) was born.

From Desert Nomands to Benedictine Monks

The history of Parmesan cheese begins in Italy

during the Middle Ages. In fact, many claim that the production process of Parmesan

cheese has not changed in over 800 years. First made, and later perfected by

Benedictine and Cistercian monks of the Po Valley, the production of Parmesan

cheese gave rise to some of Italy's first cheese dairies.  These

dairies, located in the Po Valley, between the Apennines and the right bank

of the Po River came to be known as the "cradle of parmigiano-reggiano"

in the twelfth century. During the thirteenth century the regions of Emilia

and Lombardy (known as Longobardia) was the site of many Benedictine granges

(large swaths of land dedicated to cattle). The Benedictines chose sites near

rivers and streams for two main reasons: "reflected a need for easy of

communication and the possibility of exploiting waterresources in the interests

of irrigation" (De Roest & Paini).

These

dairies, located in the Po Valley, between the Apennines and the right bank

of the Po River came to be known as the "cradle of parmigiano-reggiano"

in the twelfth century. During the thirteenth century the regions of Emilia

and Lombardy (known as Longobardia) was the site of many Benedictine granges

(large swaths of land dedicated to cattle). The Benedictines chose sites near

rivers and streams for two main reasons: "reflected a need for easy of

communication and the possibility of exploiting waterresources in the interests

of irrigation" (De Roest & Paini).

The monks in this area cultivated clover and lucerne, two types of forage important in the production of parmesan cheese. Cow's milk, a necessary ingredient in parmesan cheese, is heavily influenced by the food which the cow eats: in this case, the clover and lucerne cultivated in the Po River Valley of Italy. Not only were monks good farmers and good breeders, but their experimentation with the prodcution of cheese facilitated the discovery of parmesan cheese. Through experimentation in their kitchens and laboratories, the monks discovered that double heating the cow's milk produced a paste-like substance that would later, under watchful eyes, yield parmesan cheese.

Benedictine Monks and the Production of Parmigiano-Reggiano

Many accept the idea that the Benedictine monks were the first to produce Parmigiano-Reggiano in the areas where it is still produced today. There are several hypotheses as to why the Benedictine Monks were the first to produce Parmigiano-Reggiano.

1) Before the Benedictine monks settled in what is known today as the Parmigiano-Reggiano production area, there were no cattle herds large enough to support the production of cheese. There is no evidence documenting the existence of cheese dairies in this region.

2) The Benedictine monks reclaimed land along

the Taro River that flowed from theApennines in the Province of Parma. This,

"combined with forest clearance, enabled them to convert the extensive

gifts of

land received from both private citizens and from the civil and religious authorities

of the time into productive farmland. The land reclaimed in this way was used

to grow the crops of the day (cereals and leguminous grain), and on the plains

to the south of the River Po permanent meadows or pastureland

were created. These provided the support necessary for the development of the

large herds of cows used for milk production" (De Rost & Paini).

3) The process of making Parmesan cheese required the heating of milk in large vats to achieve the desired outcome, "This required more knowledge than could be gained from practical experience. It was only in the setting of the Benedictine abbeys that it would have been possible to develop the sophisticated techniques used. They were derived from an attentive and meticulous observation of the bio-chemical processes that occurred as the cheese was processed and ripened" (De Roest & Paini).

4) Benedictine monks have a long history of producing cheese in various parts of Europe, "Many typical European cheeses are named after Benedictine monasteries of the period: Bellelaye, Chaligny, Beval, Briquebec, Champaneac, Chambarand, Citeax, Cluny, Conques, Igny, Laval, Mont-Des-Cats, Munster, Saint-Maur and Tamié" (De Roest & Paini).

Parmesan Through the Years. . .

The first reference to Parmigiano-Reggiano is found in an entry made in the purchasing ledger, kept for the Commune Local Council of Florence's Priors' Refectory in 1344 - the name in the ledger is Parmigiano (De Roest & Paini). However, the second oldest reference to the cheese is probably the most interesting. In the literary work, The Decameron, Giovanni Bocaccio writes, "...and there was a whole mountain of Parmigiano cheese, all finely grated, on top of which stood people who were doing nothing but making macaroni and ravioli". Additionally, if one pays close attention to Italian cuisine throughout the ages, one will find the use of Parmigiano-Reggiano in many an Italian dish. The following link connects to a page with dozens of Italian dishes, some dating back to the 16th Century, several of which call for the use of Parmigiano-Reggiano.

Production

The production of Parmigiano-Reggiano is one with very little variation. Today, cheese farmers use new equipment, but stay true to the age-old production method. The following section will describe the entire production process.

Don't Forget! Without Cow's Milk, There Would be No Cheese At All!

Milk from the

evening milking is poured into large vats and left to settle overnight. |

![]()

The following

morning, the cream which has risen to the top, is skimmed from the surface. |

![]()

Milk from that

morning's milking is poured into the vat. * The exact proportion of

morning and evening milk used is decided upon by each particular cheesemaker. |

![]()

The milk mixture

is transferred to large cauldrons, each holding upon to 1200 kilograms

(kg) of milk. |

![]()

Natural bacterial

culture (fermented whey) is added to the mixture. This increases the

degree to which the milk is soured and ensures that the cheese reaches

adequate amount of fermentation. |

![]()

The milk mixture

is heated to 30 - 35 degrees Celsius and stirred continuously to ensure

uniform heat distribution. |

![]()

Rennet (a natural

coagulent derived from cow stomach lining) is added after the heating

process is finished. After 1-15 minutes, the coagulation process is

complete. |

![]()

The result

of coagulation is curd or cagliata. The cagliata is broken up with a

special instrument. This entire process is undertaken at a low heat. |

![]()

| The heat is turned off and the curd is scraped from the bottom of the cauldron with a wooden shovel and then placed on a filter sheet. |

![]()

| The curd is left for 2 to 3 days on this sheet. A large ball forms, is divided in half, and placed in form wrappings (this give the cheese its shape, the round wheel). |

![]()

| The cheese is immersed in a saltwater solution (this process is referred to as being "salted") and later placed on special wooden shelves. |

![]()

| For a period ranging from two to three years, the cheese is periodically checked, turned over, and scraped. This is known as the seasoning process. |

As one can see, the production of Parmigiano-Reggiano is a complicated, intricate process. Although new technologies have been introduced, the actual production process remains similar to production processes used hundreds of years ago.

From the Past to the Present . . .The History of the Dispute

| 1958 | WTO: Lisbon Convention establishes the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). As a participant, Italy ascribes to Article 3: “Protection shall be ensured against any usurpation or imitation, even if the true origin of the product is indicated or if the appellation is used in translated form or accompanied by terms such as ‘kind,’ ‘type,’ ‘make,’ ‘imitation,’ or the like” |

| 1992 |

European Commssion establishes Article 13 which is identical to Article 3. Within Article 13 is Regulation #2081/92, which officially recognizes and defines protected designation of origin status (PDO) for agricultural products and foodstuffs. |

| 1996 | Producers of Parmigiano-Reggiano registered the Italian name (Parmigiano Reggiano) with the European Union (EU) as a PDO product. As such, the Consorzio del Formaggio Parmigano Reggiano owns the name Parmigiano-Reggiano |

| 1999 | The Consorzio del Formaggio Parmigiano Reggiano files a complaint against the Italian cheese producer Nuova Castelli.The complaint charges that the cheese firm is selling a product with a misleading name and lacks the characteristics of PDO Parmigiano Reggiano. |

| 2002 | The European Court of Justice rules that Parmesan is not a generic term and that the defendant Nuova Castelli) may not produce “Parmesan” in Italy where the “Parmigiano Reggiano” is a registered product. |

On June 12th of 1996, the European Commission (EC) issued a list of 318 European secured products and foodstuffs that cannot be reproduced, “in close resemblance and called by same name as the original”. Many saw this as an intitial attempt to combat what some in the European Union call "agro-piracy". Currently, this list stands at 577 products and foodstuffs. Of this list of 577, Italy has 117 listed products. These listed products are the source of over 300,000 jobs in the Italian workforce and create 5.5 billion lire . Of these 117 products and foodstuffs, thirty of these various products and foodstuffs are cheese. Parmigiano-Reggiano is one of these thirty cheeses. Granted protected designation of origin status by the European Commission (EC), Parmigiano-Reggiano can only be produced in designated regions within the zone of origin: Parma, Reggio, Emilia, Modena, Mantua, and Bologna. However, it soon came to the attention of the Parmigiano-Reggiano consortium (563 cheese-producer members allied with 7000 milk producers), that Parmigiano-Reggiano of inferior quality was being sold under the name of Parmesan. As a result, during the fall of 2002, a court case was brought before the European Court of Justice addressing whether the terms Parmigiano-Reggiano and Parmesan are identical. If in fact the two terms are identical, the protected designation of origin status granted to Parmigiano-Reggiano would be extended to the term, Parmesan. The court ruling would ultimately affect fifteen European Union (EU) member states that produce cheese under the name, Parmesan.

3. Related Cases

GRAPPA - This TED case study focuses on the dispute between the European Union (namely, Italy) and South Africa concerning the protection of the alcoholic drink, Grappa. Italy claims that Grappa was invented in their country and as such, they should have the sole rights to the name.

FETA - This TED case study describes the production and history of feta cheese and the struggle by the Greeks to gain PDO status for this cheese.

SCOTCH - This TED case study focuses on the sole ownership of the name, Scotch Whiskey, by Scotland.

PISCO - This TED csae study describes the dispute between Peru and Chile over which country has the "right" to produce the product known as Pisco.

TEQUILA - This TED case study examines Mexico's push to protect Tequila in international trade agreements, by protecting it as a geographically indicated product.

KIMCHI - This TED case study describes the dispute between South Korea and Japan concerning who owns the rights to South Korea's self-proclaimed national dish.

BASMATI - This TED case study focuses on the name, Basmati. Usually reserved for a certain type of rice grown in India, in 1997 a U.S. company was granted a U.S. patent to call Basmati-style rice grown outside of India, Basmati. Intended for international export, both India and Pakistan became increasingly worried about the affect of this patent upon their own share of the Basmati market.

NEEMTREE - This TED case study examines the dispute between the United States and India over the use of the Neem tree. A U.S. company, which owns the patent to the process which produces the emulsion necessary for various medicinal needs, has been suing Indian companies using the same process.

4. Author and Date:

Elizabeth Jahncke. April 2003

5. Discourse and Status: Disagreement and Completed.

As a participant in the Lisbon Convention of 1958, Italy was present at the birth of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Also as a participant, Italy ascribed to Article 3 of the Lisbon Convention which specifically addressed the protection of agricultural products and foodstuffs. Article 3 states that, “Protection shall be ensured against any usurpation or imitation, even if the true origin of the product is indicated or if the appellation is used in translated form or accompanied by terms such as ‘kind,’ ‘type,’ ‘make,’ ‘imitation,’ or the like” . Article 3 of the Lisbon Convention was an important precursor to the European Commission’s Article 13. In fact Article 13 and Article 3 of the Lisbon Convention are identical. However, it was Regulation #2081/92 that recognized protected designation of origin status (PDO) for agricultural products and foodstuffs.

What is a PDO?

"It is about the name of a region, a determined place or in, in exceptional

cases, of a country, which serves to designate agricultural products or foodstuffs

coming from this region, this determined place or this country, and where the

quality or the features are essentially or exclusively due to a geographical

area consisting of natural and human factors and where the production, processing

and development are placed in a defined geographical area."

Additionally, Regulation #2081/92 allows that, “undertakings that have

been legally marketing products under a denomination which was subsequently

registered for protection may continue to do so for five years after registrations

even if the products do not comply with the official requirements of the registered

denomination of origin”. As such, producers or even EU member states are

given a 5 year period to cease production of the protected product.

THE DISAGREEMENT

In 1996, producers of Parmigiano-Reggiano registered the Italian name (Parmigiano Reggiano) with the European Union (EU) as a PDO product. Currently, the Consorzio del Formaggio Parmigano Reggiano owns the cheese trademark (the name, Parmigiano Reggiano). As such, this dictates that in order to have the name, Parmigiano Reggiano, the producer must be located in a certain region within Italy (namely the Parma and Reggio Emilia regions). However, although granted PDO status in 1996, the Consortium filed a complaint against Nuova Castelli (an Italian cheese producer) in 1999. Produced in Italy, the product was a dried, grated, pasteurized cheese labeled under the name of Mr. Bigi Parmesan. The product, although made in Italy, was solely intended for exportation to France and it was the intended destination that proved especially problematic for Nuova Castelli. The Consortium claimed that the French word, Parmesan, was the direct, literal translation of the Italian words, Parmigiano-Reggiano. Because the two words are interchangeable - in fact, meaning the same thing - the complaint filed by the Consortium argued that Nuova Castelli was selling a product with a misleading name: that the product lacked the characteristics of PDO Parmigiano Reggiano.

LEGAL PROCEEDINGS

Italy takes on Nuova Castelli and 5 other EU Member States. . .

Germany Greece Austria France Portugal

The Italian cheese firm, Nuova Castelli (producers of Mr. Bigi

Parmesan) argued that the product was labeled Parmesan, not Parmigiano Reggiano

and as such, was not in violation of Regulation #2081/92. The case first appeared

in the Tribunal di Parma and was later referred the European Court of Justice

in Luxembourg. Italy, as well as Germany, Greece, Austria, France, and Portugal

submitted observations on the case. These observations argued either in favor

of Nuova Castelli or in favor of the Consorzio del Parmigiano Reggiano. In their

argument, Germany maintained that “Parmesan” was a generic term

describing grated cheese or cheese intended for grating, and as such, should

not be granted PDO status. For example, Swiss cheese is a generic term describing

cheeses that have a pale yellow, slightly nutty-flavored flesh with large holes.

However, the Consorzio del Parmigiano Reggiano argued that Parmesan was a direct,

literal translation of Parmigiano Reggiano – that the terms were identical

in meaning and, as such, PDO status must be extended to Parmesan.

THE OUTCOME

On June 25, 2002 the European Court of Justice ruled that Parmesan

was not a generic term and that the defendant (Nuova Castelli, producer of Mr.

Bigi Parmesan) could not produce “Parmesan” in Italy (even if it

was intended for exportation to France) where the “Parmigiano Reggiano”

is a registered product. The European Court of Justice also ruled that once

a member state has applied for the registration of a name as a PDO, products

that do not comply with its (the product’s) specification(s) cannot be

legally marketed within that particular country or any in the EU.

This marked a substantial victory for the Consorzio del Parmigiano Reggiano.

They now not only owned the rights to the name of Parmigiano Reggiano, but also

to its direct, literal translation, Parmesan. As such, any product in the EU

labeled Parmesan was sure to have been produced in the designated region of

origin. For example, Kraft Foods,

an American company also sold a version of "Parmesan" cheese throughout

the Euroepan Union; however, with the June 25th ruling, Kraft changed the name

of its product to Pamsello. Although the Parmesan case directly dealt with the

contested PDO status, it is useful to be aware of another means through which

countries may protect their agricultural products or foodstuffs.

Geographical Indicators (GIs)

A geographical indicator, also known as a geographical appellation, is a status of designation, "given to a good or product which identifies it as coming from a certain country, region or locality to which some quality or recognition is attributed"(Gunawardana). A geographical indicator is intended to assure consumers of the genuine nature of the product - that certain expected qualities and characteristics have been met. Additioanlly, GIs protect the original product from those intending to make a profit by producing an inferior product while using the name of the well-known GI (mislabelling). Some examples of well-known products with geographical indicators are: "Scotch Whisky, Champagnes, Bordeaux wines, Burma Teak, Ceylon teas, Darjeeling teas (produced in the Darjeeling hill tracks of West Bengal, India), Thai rubies, Sri Lankan Blue Sapphires and Basmati rice (long, narrow grained, aromatic rice grown in India and Pakistan)" (Gunawardana).

Much like the the status of PDO, the GI has a long history within the European Community. We may thank the French for pioneering both the term and its actual use. It was the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (Paris Convention) that first mentioned a concept similar to the GI - industrial property: "the term 'industrial property' covers all manufactured or natural products such as wines, tobacco, leaf, fruit and grains crops, cattle, minerals, mineral water, beer, flowers and flours. It provides that the protection given for industrial property includes 'indications of source or appellations of origin'"(Gunawardana). This convention has been modified and amended seven times, with the last time being in 1979 finally stating that, "members should take measures to prevent direct or indirect use of a false indication of the source of goods or the identity of the producer, manufacturer or trader"(Gunawardana).

The Convention that deals directly with GIs

is the Lisbon Convention of 1958; however, this convention has only 18 member

states. Of greatest relevance to this particular case study are the international

dynamics of the GIs. The trade related aspects of intellectual property rights

agreement (TRIPS) under the WTO maintains that, "all member states should

ensure that GIs of other member states are protected within their territories"(Gunawardana).

Additionally, the European Union has enforced the recognition of GIs through

the regulation, Geographical Indicators and Designations of Origin (No 2081/92)

of 1992. This regulation, "denotes a product that is prepared or processed

or produced in a geographical area and a specific quality, reputation or a characteristic

is attributable to the area" (Gunawardana). Within this regulation, a protection

of geographical indication (PGI) is less broad in scope than a PDO and in this

way, can be used to protect the reputation of a product, "It is

only necessary to attribute a character to the region and is not necessary to

show that it is essentially due to some unique factor (human or other) that

relates to an area"(Gunawardana).

The PGI is intended to prohibit the production of inferior (and often cheaper)

imitations. Additionally, it protects against the problem of mislabelling, prohibiting

others from stating their product is like or in a style similar to that of the

original, "This protection prevents others from even stating that their

products are 'Similar to' the 'type of', made in the 'style of', or using the

same 'way', 'method' or 'process' of a GI, or any other similar expressions"(Gunawardana).

Broader than a trademark (which applies only to ther person or company that

registers it), the GI "can be freely used by all those who qualify to use

it, along with and as a complementary to their respective trademarks" (Gunawardana).

6. Forum and Scope: Interregional and Multilateral

WTO/Lisbon Convention

European Community Regulations

7. Decision Breadth: European Union

8. Legal Standing: Law/Treaty

9. Geographic Locations

a. Geographic Domain: Europe

b. Geographic Site: Western Europe

c. Geographic Impact: Italy

10. Sub-National Factors: No

11. Type of Habitat: Temperate; mostly rugged and mountainous with some plains and coastal lowlands.

12. Type of Measure: Intellectual Property Rights; Barriers to Trade

Intellectual Property Rights: The

granting of protected designation of origin status to Parmigiano reggiano symbolizes

the protection of the process involved in producing Parmigiano reggiano. Italians

claim that Parmigiano-Reggiano has been produced in the same manner for over

700 years. The twelve-step process is strictly adhered to and variation only

occurs in the proportions of evening and morning milk used by each, individual

farmer. In short, the intellectual property (the know-how) is protected with

the end product (parmigiano-reggiano and parmesan) benefiting this protection.

Barrier to Trade: The

PDO status mandates that only certain reginons in Italy may produce Parmigiano-Reggiano

- as such, Italy has a (natural) monopoly on Parmigiano-Reggiano production.

If Italy attempts, and succeeds, inextending PDO status on a global basis, this

status would be a barrier to trade in that other countries could not import

Parmigiano-Reggiano or Parmesan into Italy and, they also could only import

Italian-made Parmigiano-Reggiano or Parmesan into their own countries.

13. Direct v. Indirect Impacts:

Within the EU, the impact of measures like protected designation of origin status, directly affects the trade flows of the product. In this particular case, within the EU, Parmigiano-Reggiano can only be exported from certain regions within Italy. At the same time, this means that Parmigiano-Reggiano can only be imported from Italy. As such, it would appear that Italy has a (natural) monopoly on the Parmigiano-Reggiano market.

14. Relation of Trade Measure to Environmental Impact

a. Directly Related to Product: Yes

b. Indirectly Related to Product: Yes, Agriculture

c. Not Related to Product: No

d. Related to Process: Yes: Intellectual Property

15. Trade Product Identification:

16. Economic Data

TOP TEN EXPORTERS BY COUNTRY

Measurements are in Quintals - 10 Quintals is = 1 metric ton

| 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | |

| Italy | 177.607 | 170.268 | 179.086 | 205.233 | 216.035 | 238.255 | 274.020 | 324.579 | 354.441 |

| Austria | 3.399 | 2.938 | 2.348 | 3.366 | 4.135 | 4.786 | 5.550 | 6.484 | 9.760 |

| Belg/Lux. | 6.781 | 7.071 | 7.711 | 9.274 | 10.215 | 11.136 | 12.428 | 13.065 | 13.145 |

| Denmark | 426 | 606 | 1.564 | 1.943 | 1.873 | 2.271 | 2.882 | 3.769 | 4.425 |

| France | 15.581 | 17.025 | 21.076 | 21.416 | 22.085 | 24.317 | 29.330 | 34.978 | 35.031 |

| Germany | 18.881 | 21.074 | 23.345 | 29.245 | 31.850 | 36.554 | 42.862 | 52.918 | 57.542 |

| Greece | 1.288 | 1.897 | 1.882 | 2.110 | 2.613 | 3.392 | 4.413 | 6.137 | 7.482 |

| United Kingdom | 9.481 | 11.328 | 11.595 | 14.224 | 17.578 | 19.713 | 23.510 | 26.386 | 28.078 |

| Spain | 3.351 | 2.605 | 2.613 | 3.069 | 3.888 | 5.867 | 11.438 | 11.773 | 9.376 |

| Sweden | 731 | 931 | 692 | 1.153 | 1.546 | 2.418 | 3.041 | 3.395 | 4.029 |

| Switzerland | 44.769 | 44.769 | 44.721 | 46.937 | 50.019 | 49.114 | 49.727 | 56.690 | 65.498 |

Obtained from http://www.parmigiano-reggiano.it/ - official website of the Parmigiano-Reggiano Consortium

17. Impact of Trade Restriction: Italy dominates the Parmigiano-Reggiano/Parmesan cheese markets and continues to grow.

18. Industry Sector: Non-Durbale Manufacturing: Foods

19. Importers and Exporters:

Production of Parmigiano-Reggiano Within Italy, By Province

January - April / May - August

| Province | 2001 | 2002 | 2001 | 2002 | ||||

| # of Wheels | # of Wheels | # of Wheels | # of Wheels | |||||

| Bologna | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | ||||

| Mantova | 108 | 110 | 106 | 105 | ||||

| Modena | 194 | 201 | 202 | 199 | ||||

| Parma | 347 | 359 | 350 | 357 | ||||

| Reggio Emilia | 300 | 303 | 306 | 311 | ||||

| Total | 970 | 994 | 985 | 993 |

Parmigiano-Reggiano/Parmesan Cheese Producing Dairies in Italy

Reggio Emilia and Parma produce the most Parmigiano-Reggiano/Parmesan Cheese

per wheel than all other regions within the zone of origin.

Reggio Emilia and Parma produce the most Parmigiano-Reggiano/Parmesan Cheese

per wheel than all other regions within the zone of origin.

There are eight cheese producing dairies in Reggio Emilia.

There are eight cheese producing dairies in Reggio Emilia.

| Nuova Castelli | Giglio | Peiffe Di Dr. Pietro Fanticini | Dalter Alimentari Spa. | Figli Di Bruno Cantarelli Spa. | Parmareggio Spa. | Bertoni Spa. | Rossi R. LLI Spa |

There are eleven cheese producing dairies in Parma

There are eleven cheese producing dairies in Parma

| Abele Bertozzi Spa. | Cantarelli Spa. | Boni Spa. | Gruppo "A Bizzozzero" Per L'esportazione SCARL. | Greci Gaoine Spa | Guido E. Figli |

| Biemme SRL. | Gennari Sas. | Fornaciari Spa. | La Fattoria Parma | Maghenzani Cav. |

* Nuova Castelli was at the center of the legal proceedings determing whether Parmesan was a generic term or whether it deserved PDO status.

Importers of Parmigiano-Reggiano Within the United States. . .

New York . . . New Jersey

Bel Canto Fancy Foods

Advantage Foods International

Advantage Foods International

D. Coluccio & Sons,

Inc.  Battaglia & Co.,

Inc . . . . . . . .

Battaglia & Co.,

Inc . . . . . . . .

Dairyland USA .

. . . . . .  Ambriola,

Inc... . .. . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Ambriola,

Inc... . .. . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Fresh Direct ..>>>>>>

Arthur Schuman,

Inc.. . . . . . . ..

Arthur Schuman,

Inc.. . . . . . . ..

L.

Della Cella, Co. . . . .  Atalanta Corporation

Atalanta Corporation

Musco Food, Co. .

. . . ..  Cheeseworks

Cheeseworks

Schroeder Brothers

. . . .  Gourmet Italia Imports

Gourmet Italia Imports

Sini Fulvi USA .

. . . . . . . SFI

Anco Fine Cheese

SFI

Anco Fine Cheese

.

. .. . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . Swissrose

International

Swissrose

International

. .

. . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Walker

Foods

Walker

Foods

20. Environmental Problem Type: N/A

21. Name, Type, and Diversity of Species

Name: N/A

Type: N/A

Diversity: N/A

22. Resource Impact and Effect: N/A

23. Urgency and Lifetime: N/A

24. Substitutes: N/A

25. Culture: Yes

Italians take both their agricultural products and foodstuffs quite seriously. Although some may say that this seriousness is of a purely economic nature, I would question this type of thinking.

There is a reason that the motto of the Consorzio del Parmigiano Reggiano is, Non si fabrica, Si fa - it is not made, but rather, produced. Dating back to the days of Boccaccio and The Decameron, Parmigiano-Reggiano has a pronounced place in Italian history. From the Benedictine monks of the Middle Ages to the small dairy farmers of today, the actual production process of Parmigiano-Reggiano has changed very little over time.

There is, quite literally, a festival for every major Italian foodstuff or agricultural product. From garlic to Chianti, the celebration of Italian food is witnessed through the myriad of festivals celebrated throughout Italy during the year. In mid-July, the Festa del Parmigiano di Montagna, takes place in the region of Parma.

Click

on this image to view more information about Italian food festivals.

Click

on this image to view more information about Italian food festivals.

The history of Parmigiano-Reggiano speaks of the history of Northern Italy. Thought to have been a dismal wetland, the area fell into decline shortly after the collapse of the Roman Empire. It wasn't until monks began inhabiting the area that the region became productive. As monastic orders began reclaiming land in this region, they drained and cleared the land, making it suitable for farming and cattle breeding. As arable land gave way to pastures, new settlers moved in, and soon, towns began to sprout in close proximity to the monasteries. As times have changed, one thing has remained constant - the production method of Parmigiano-Reggiano. Although new technologies have emerged, very little of the actual production process has changed. As such, the old Italian adage, Non si fabrica, Si fa, still rings true today.

26. Trans-Boundary Issues: No

27. Rights: Intellectual Property

28. Relevant Literature

Official Website of the Parmigiano-Reggiano Consortium: http://www.parmigiano-reggiano.it

Dott Kees De Roest - Dott. Luigi Paini. EU-India Working Paper 01: Relevant Issue on the Production of Parmigiano-Reggiano Cheese

Midweek Review. "Geographical indications: Protecting quality and reputation". Jagath Gunawardana. http://origin.island.lk/2002/05/22/midwee02.html

Report Commissioned by The Italian Ministry of Agriculture, Food Industries, and Forestry Resources: "Italian Cheese. The Quality of Life." 1995.