| ICE Case Studies

|

|

I.

Case Background |

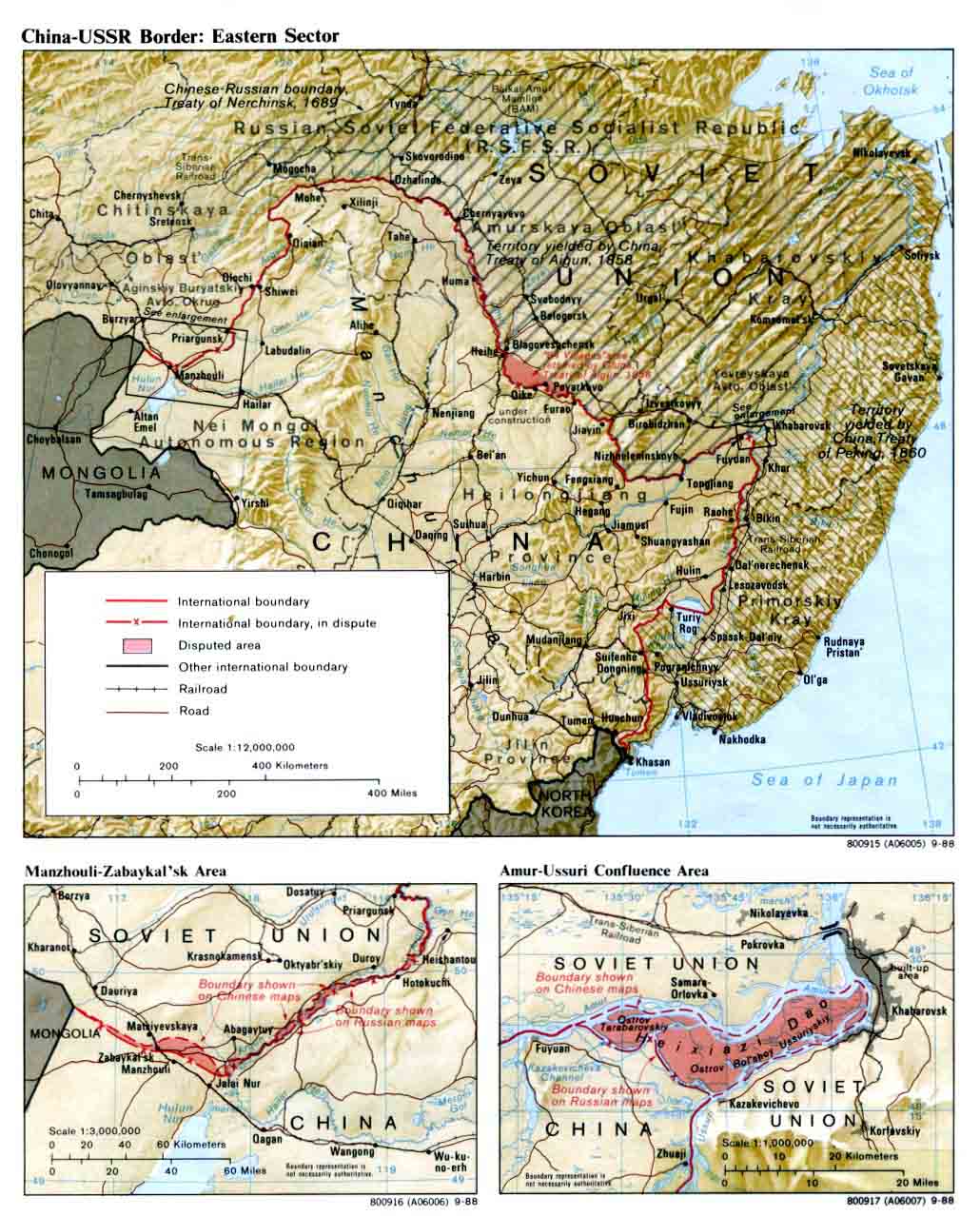

There is a long border between China and Russia. In history, there used to be large- scale military conflict for these borders. Since the seventeenth century when Tsarist forces occupied Nerchinsk and Yakasa in the Amur region (north of Mongolia and west of northern Nei Mongol). The eighteenth century saw Russian incursions in the Lake Balkhash area, near Northwest Xinjiang. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Russians had seized a total 1.4 million square kilometers, and another 1.5 million by 1900. The Russians codified these gains through a series of 'unequal treaties,' as current Chinese histories call them.

Beijing government began to challenge Soviet occupation of these disputed areas in 1963, and, with China's demonstration of its nuclear capability in 1964, the military build-up on both sides of the border began in earnest. In Japanese press, Mao was quoted as saying that both Vladivostok and Khabarovsk were on territory that had belonged to China save for 'unequal treaties.'

Soviet ground forces had been augmented in the last half of 1967 in regions bordering China in the Far East and Transbaykal Military Districts. From 1965 to the end of 1969, the USSR increased its deployment of ground forces in the military districts adjacent to the Chinese border from 13 divisions to 21 divisions.

Sharp border clashes between Soviet and Chinese troops occurred in 1969, roughly a decade after relations between the two countries had begun to deteriorate and some four years after a buildup of Soviet forces along China's northern border had begun. The Zhenbao/Demansky Island conflict flared up in March 1969, and then spread from the Ussuri River along the border into Central Asia. Particularly heated border clashes occurred in the northeast along the Sino-Soviet border formed by the Heilong Jiang (Amur River) and the Wusuli Jiang (Ussuri River), on which China claimed the right to navigate.

Nowadays,

despite the fact that some basic disputations along the border have been solved

by both sides, the fight about two islands in Amur River have been getting fierce.

Before the demise of the Soviet Union, China and Soviet Union started to negotiate

for the controversial and uncertain borders. The reasons of uncertain border

are mainly reagarding to the history since Chinese Chin dynasty. In history,

China haven't had clear demarcation until the near times, not to mention the

borders of Northeast, Northwest or Southwest where only few people inhabited.

In the near times, China faced the invasion from many other countries, Russia

especially fiercely in so doing and the best way for evading the charge of "invasion"

is to claim uncertain territory.

Nowadays,

despite the fact that some basic disputations along the border have been solved

by both sides, the fight about two islands in Amur River have been getting fierce.

Before the demise of the Soviet Union, China and Soviet Union started to negotiate

for the controversial and uncertain borders. The reasons of uncertain border

are mainly reagarding to the history since Chinese Chin dynasty. In history,

China haven't had clear demarcation until the near times, not to mention the

borders of Northeast, Northwest or Southwest where only few people inhabited.

In the near times, China faced the invasion from many other countries, Russia

especially fiercely in so doing and the best way for evading the charge of "invasion"

is to claim uncertain territory.

In 1990s, both sides finished the demarcation of western and eastern borders except two small islands in Amur River. Damansky Island (Jenbao), a place of a military skirmish, demarcated as China's territory. Since these two islands have economic and military value, both sides show no sign to give up. After the demarcation in 1990s, Russia officials said that these two islands should be left for the next generation to solve. But recently, these two islands stirred new wave of arguments.

The names of these two islands are Bolshoi Ussurisky and Tarabarov, located few miles from a big Russian city Khabarovsk. These two islands contain two important meanings. One is the economic value; another is strategic value. Because these two islands are in the center of Amur River, divide Amur River into two sections, these two islands belongs to either side will symbol which side has more control over the Amur River. For hundreds of years, with the change of climate and geography, these two islands and the Russian side has been the main channel. These two islands moved closely to the Chinese side. According to the agreement concerned this area reached by China and Russia in 1990s, the border in Amur River should be divided by the main water channel so that these two islands will belong to China. However, Russia said that according to the Peiking Treaty made by 1860, the border should be divided the area between these two islands and the Chinese side, so that these two islands should belong to Russia. According to research, trout and some cherished fish species act mostly in the main water channel. So who owns these two islands means who can control the economic resources. In term of military strategy, these two islands face the big city, Khabarovsk. Based on the saying of Russian military official, these two islands are the natural barriers for protecting Khabarovsk. Once these two islands belong to China and conflict happened between these two countries. It will be no way to keep Khabarovsk free from safety because Khabarovsk city is too close to these two islands.

The action for obtaining these two islands seemed getting flagrant recently. According to the report of Russia, China sunk boats loaded with sand and rocks in the side of China as well as put sands and rock on top of the icy Amur River. Once spring approaches, the sands and rocks will sink into the waterbed. That will make the water channel become so shallow as to connect with Chinese land and belong to China, which causes the fact that these two islands belong to China territory. In Russia, Russian sent military service in these two islands and encouraged Russian farmers to cultivate crops as well as build resort. Orthodox churches were built in these two islands in memory of the dead soldiers devoted to the fight in 1969.

Historical Background of the Amur Conflict:

First Russian eyewitness account of China (Petlin expedition)

There is a natural tendency to view Sino-Russian relations the perspective of the past twenty years, when Communist regimes have ruled in both countries. In historical fact, however, the greatest proportion by far of the Sino-Russian relationship has fallen in the imperial stage of the two countries, during the respective rules of the Manchu (1644-1912) and Romanov (1613-1917).

First direct contact of Russia with China dates back to the beginning of the 17th century, when Mericke, the English representative of London's Moscow Company became interested in the Ob (Russian Siberian river) as early as 1611. He requested, in addition to general privileges for English merchants in Russia, specific permission for Englishmen to travel to Persia through the Volga and to seek a route to China and India through the Ob. The Russians refused him but offered to ask the Siberian voevodas (commanded the troops, supervised the construction and defense of the new towns and blockhouses, and administered both civil and military affairs) to obtain information concerning the Ob.

On April 6, 1617, Tomsk voevodas under the direction of Ivashko Petlin were send on this mission, its expenses came from the state fur treasury. Ivashko Petlin left a detailed account of his journey and his impressions of China written in 1619. The expedition followed the Great Wall for ten days, during which it met no one. Peking impressed him most of all. He reported that it was a very great city, white as snow, around which it took four days to travel.

More important was Petlin's description of his activities in Peking and of the diplomatic and court ceremonial he observed. Although he had been given no political tasks and was merely to travel and observe, he appears to have been received by the Chinese as a tribute-bearing mission. This supposition is supported by the fact that he was lodged in the "Great Embassy Courtyard" (may have been the court of the Li-pu - The Board of Rites - were tribute missions were traditionally lodged), and that the question of yasak(tribute - definition) was raised in his discussion with various Ming officials, whom he failed to identify.

Four days after his arrival at Peking the court approached him as to the purpose of his visit. He claimed that he had been sent to China by the tsar "to make inquiry as to the kingdom of China and to see the tsar (the Chinese emperor)". Since his statement was unsupported by his written instructions, which he had certainly read, one can only suppose that it was curiosity, not policy, that prompted his request for an audience with the emperor. Nevertheless, his inability to present "gifts" from the tsar to the emperor as "tribute system" of China required prevented his admission to an imperial audience. The lack of "gifts" or tribute goods can be explained in two ways. First, although he had received furs enough for wages for two years and supplies enough for one, he may not have been given sufficient furs for use as gifts since his nondiplomatic status did not require them. Second, as an interpreter along the frontier, Petlin was undoubtedly acquainted with Central Asian diplomatic usage and the tribute system. Aware of the significance of such gifts, Petlin may have refrained on his own volition from presenting any to the Chinese court.

Although charged with no diplomatic tasks and excluded from imperial audiences, Petlin's mission had one curious political by-product: receipt of an invitation to the tsar to trade with China, written in the form of a letter allegedly by the Ming emperor Wan-li, but more likely penned by a minor official in the emperor's name. Although Petlin brought the letter to Moscow, the Russians were unable to find anyone to translate it until 1675: in the meantime its contents remained totally unknown. (This letter with three others was given Milescu to take back to China for translation. Of the four letters, two were in Chinese, which he was able to have translated at Tobolsk, while the other two, in Manchu, remained untranslated until he arrived at Peking). The letter appeared to be a clear expression of the tributary relationship. The author of the letter used the words "up and down" to describe the exchange of communications between Russia and China. The expression meant "the exalted station of the Chinese emperor and the inferior one of the tsar". Whereas the opening phrases of the letter referred directly to trade, the writer continued, "bring the best you have, and I in return, will make you presents of good silk stuffs". These comments, together with remarks concerning China's custom of never sending ambassadors abroad and the inability of her merchants to travel to foreign markets, gave a close description of the tribute system , which reached a high point of development in the late Ming.

The First Sino-Russian Conflict:

The territorial dispute between the former Soviet Union and China in 1960's was an extension of a long existing conflict, that can be traced back to the 17th century. It broke down when in 1628 the Russians invaded the territory inhabited by the Buryats, a Mongol People living west of Lake Baikal. A series of expeditions established blockhouses, while other expeditions were drawn further into eastern Siberia, beyond the lake, by rumors of fur, gold, and silver, Fur was in fact quite plentiful in eastern Siberia, and gold and silver could be had from Mongolia in exchange for pelts, but climatically the area was inhospitable, and the Russians were sorely pressed for food. The earliest arena for Russo-Manchu confrontation was the Amur River Valley. The appearance of the Russians there in the 1640's was a logical development in the rapid expansion of Russian power across northern Asia. It posed the problem of Russia's relation to the Ch'ing tribute system. The result was determined partly by the aims and methods of Russia's eastward expansion.

Poyarkov Expedition

The colonists received their first definite information about Amuria (the Amur watershed) after the establishment of Yakutsk in 1632. Using the new settlement as a base of operation hunters followed the Lena River to its mountainous source and at the same time discovered the Shilka and the Zeya, two streams lying beyond the mountains and outside the Lena river system. On the banks of these rivers they met natives who told of fertile grain fields along the Amur to the south. Maxim Perofilliev, an early expedition leader, made one of the first such reports to Yakutsk in 1641. He had met a Tungus, a member of an eastern Siberian mongoloid people related to the Manchus, who had visited the country of the Amur, observed its population, and noted its agricultural and mineral resources. But no one reported that the inhabitants of this distant unknown region had already been drawn within the power penumbra of the Manchu international order in East Asia.

The first attempt to collect direct information about the rumored riches of the Amur was made in 1643. The voevoda (war worrier) of Yakutsk was in perpetual need of outside grain supplied. He appointed Vasily Pyarkov leader of a new expedition. According to Poyarkov's instructions, he was to proceed up the Lena, the Aldan, and one of its branches, whence he would cross the mountains to the source of the Zeya and sail down it to the Shilka. He was also to inquire into the relations between the natives and China, determining whether and for what purpose Chinese officials visited the region.

The Poyarkov expedition was significant in several respects. First, it provided the first Russian eye-witness information about the Amur and its resources. Second, it alienated the local inhabitants along the Amur and warned the Manchus of the Russian approach, enabling the Manchus to take steps to stop the barbarian invasion. Third, the expedition demonstrated that the Aldan-Zeya route was not suitable for mass Russian immigration to, or grain transportation from, the Amur region. If the resources of the area were to be exploited, the problem of geographical access had to be solved. Khabarov's expeditions to (See the map):

The second important attempt to conquer the Amur was made by Erofei Pavlovich Khabarov. First expedition from Yakutsk, he followed the Olekma route and reached the Amur with little difficulty in May, 1650. By the summer of 1650 Khabarov had equipped a new expedition and returned to the Amur. For four days the expedition passed through destroyed or deserted settlements, until they reached a village named Guigudar. Here, evidently for the first time, Khabarov encountered several Manchus, who refused to fight, claiming that they were under strict orders to avoid conflict with the Russians. On September 7, Khabarov Boarded his boats and sailed out of the country of the pastoral Duchers and Dahurs, who were vassals of the Manchus past the mouth of the Sungari River, and into the country of the Achans, a fishing tribe. The Achans at first appeared friendly, but a combined Achan-Ducher force numbering between eight hundred and one thousand men attacked the Russians on the night of October . Superior arms gave the Russians the victory. The Manchus apparently understood neither the nature of their enemy nor the fact that the campaign was not simply a raid on their territory but the forerunner of a concerted Russian colonization attempt.. Khabarov himself reported that his men had killed 676 Manchus; he lost only ten Cossacks (Russian army troops) killed and seventy-eight wounded.

The battle at Wu-cha-la was only the first step in the development of a Manchu military response to Russian incursions into the Amur River basin. The initiation of an active Manchu policy changed the situation in Amuria, forcing the Russians to develop new tactics and concentrate on a concerted approach to actual settlement. Reports to voevodas began to state that the presence of Manchu troops in a given region prevented the Cossacks (Russian army troops) from venturing far into hostile territory. The effects of the withdrawal of the Manchu forces before achieving victory were mitigated, it would seem, by the restrictions that the new situation placed on Cossack movements.

Khabarov's departure marked the end of the period of raids on the Amur and the beginning of a period of attempts at permanent settlement, based on the realization that only thus would the Amur be incorporated into Russia's territories. But the situation in Amuria in the forties and fifties of the seventeenth century was significantly different from the situation in Siberia fifty or sixty years earlier. The defeat of the Khanate of Siberia between 1579 and 1584 had eliminated any element capable of opposing the spread of Russian power from the Urals to the Pacific Coast of northeastern Siberia. In the Amur Valley the situation was more complex. To the south of the river was the Manchu Empire, just reaching the height of its power, whose domains included, even if only nominally, those areas occupied by the natives of the Amur basin. The tactics employed by Poyarkov and Khabarov, which had earlier worked so well in Siberia, could only rouse the Manchus to further action to protect their subjects and their interests. Attempts for Russian settlements at Amur basin:

The Manchus now made further preparations to push the Russians from the Amur. Peking's preparations for the struggle continued apace, and on June 30, 1658, a conflict took place on the Amur just below the mouth of the Sungari. The Manchu victory was due largely to their use of water forces and the evacuation of the natives, which increased the supply difficulties of the Russians at Kumarsk. The Manchu victory of 1658 cleared the Amur of official Cossack bands as far as Nerchinsk (See the map).

The Russians were at first reluctant to return to the area from which they had been expelled, and their inactivity in Amuria encouraged the Manchus to sink back into inaction. Thus, a favorable situation was created for the return of the Russians in greater force with ideas of a more permanent settlement.

The influx of outlaws further strengthened the Russian hand. The most significant outlaw group was established in Albazin. In late 1665 Polish exile in Siberia killed their guard voevoda and to avoid punishment, the Pole crossed the mountains to the basin of the Amur. There they reached Albazin, the former capital of Albazi. Albazin was build in the form of a square: each side was 120 paces long, with one side facing the Amur. The settlement prospered as a gathering place for Russian adventurers and outlaws. In 1671 Ivan Olukhov was sent from Nerchinsk to take command at Albazin.

Despite their initial success, the Manchu inability to carry their campaign through to its logical conclusion - complete destruction of the Russian presence in the region, including Nerchinsk - enabled the Russian government to reestablish its authority in the Amur. Expansion in the Ussuri and Sungari regions, made further conflict between Russians and Manchus inevitable.

The Manchu withdrawal after the battle of 1660, their failure to garrison the Amur, and their reluctance to push for total victory in the mid-sixties were the results of lack of proper preparation and consequently a shortage of supplies.

Positive Manchu policy toward the Russians had to await the stabilization of the Ch'ing dynasty's power inside China. With relative ease and speed the Manchus had entered China in 1644, but at least a generation passed before they succeeded in extending their control throughout the former Ming domains and beyond.

The financial and personnel drain on Manchu resources during the struggle for total control of China was sufficient to prevent the Ch'ing court from developing its northern defenses and opening an anti-Russian front in the Amur Valley. The Manchus then faced two problems to the north. First, the security of the dynasty's territorial base in Manchuria must be maintained, as was impressed upon them by their difficulties with the Chinese rebels. They therefore prevented Chinese colonization of Manchuria until the end of the nineteenth century and made efforts to secure their homeland from Russian incursions. Second, as the new occupants of the dragon throne, the Manchus needed a free hand in Central Asia, particularly in Mongolia and Sinkiang, because Central Asian nomad invasions and raids were a constant threat to any dynastic power in China. As the Russians in southern Siberia maintained close contract with the Mongols and were in a position to intervene in Central Asian affairs at will, Peking needed Russia's neutrality in Central Asian politics and recognition of her own primary role in the region.

Moscow could not be dealt with within the framework of traditional East Asian diplomacy. There existed the unfeasibility of combining the question of trade, which Moscow wanted, with the question of Russian withdrawal from the Amur, which Peking wanted. As early as the 1670's the Manchus indicated that they were prepared to exchange commercial privileges for Russian evacuation of the Cossack settlements along the northern frontier, but since Moscow could not control the Amur Cossacks at that time, it had to insist on treating the problems of trade and frontier separately.

The Russians were aware of Manchu intentions at least as early as March 1681. The Manchus demanded to know why a Russian fort had been built on the Zeya River, at a location used as a portage by Manchu officials when collecting tribute from subject tribes. In August an official arrived from the capital with an imperial edict that constituted an ultimatum for Russian withdrawal from the Zeya. The Cossacks returned to Nerchinsk with their report at the beginning of October 1681. These events marked the beginning of Russian efforts to create some kind of defense in the Amur Valley.

In 1682 the Russian position grew worse. The beginning of the construction of the Manchu base at Aigun prevented the Cossacks from sailing down the Amur in search of food and tribute. The Manchus also made a minor attack on a detachment of Albazinian Cossacks, captured some prisoners, and destroyed a series of small Russian ostrogs (define as a ford) along the Burya, Khamunua, Zeya, and Selima rivers.

Moscow's apparent determination to defend the Amur against Manchu attack could not overcome the multitude of problems involved in building a military machine in the face of the scarcity of able-bodied men in Siberia and the impossibly long command and logistic lines. The apparent lack of interest shown by other Siberian voevodas in the Amur crisis made any success even more improbable. By the time of the Ch'ing attack on Albazin in 1685, neither population nor military supplies had increased sufficiently to allow for more than a brave but vain Russian resistance.

After the completion of last-minute preparations Ch'ing forces attacked Albazin in the early summer of 1685.

On June 23, 1685, Pengcum led three-thousand soldiers in an attack on Albazin. First he read to the Russian defenders the emperor's edict demanding their surrender. During the surrender negotiations at least six hundred and probably almost all of the Russians requested permission to return to Nerchinsk. K'ang-hsi, the emperor of Munchuria, received the news of the victory on July 5, 1685, during an imperial progress in Manchuria.

On August 20, 1685, the emperor extended his clemency policy to the four helpless prisoners by abrogating their death sentences and sending them home with a final communication to the Russian authorities, which requested the return of a certain fugitives and demanded that the Russians never again invade China's frontiers.

On July 10, 1685, Shortly after Albazinian refugees arrived at Nerchinsk, they petitioned the voevoda, Vlasov, for permission to return to Albazin to harvest the crops they had sown in the spring and to reestablish the settlement. The voevoda permitted 669 men to return to Albazin, under Tolbuzin's leadership, arming them with five cannon, powder, lead, and other supplies, and assigning eight newly-conscripted soldiers to accompany them. Albazinians arrived at their former home on August 27 and proceeded to harvest the grain. With Albazin reestablished, Vlasov pursued a policy of extending Russian influence and control to its pre-1685 limits. On March 7, 1686, Tolbuzin sent a fore of three hundred men down the Amur to the Khumar River to collect yasak. Upon receipt of the report on the Russian presence, the emperor decided to initiate military action immediately. Langtan was instructed personally by K'ang-hsi to try to persuade the Russians to surrender peacefully; failing this, he was to threaten the Russians with death. He was further instructed that after the capture of Albazin the Manchu forces were to march on Nerchinsk to put a final end to the source of the difficulties on the Amur.

K'ang-hsi was anxious that the impending negotiations with the Russians begin under the most favorable circumstances. The Russian survivors of the siege were notified that the Manchu troops were evacuating the area because of the arrival of the tsar's envoy to discuss peace. In this way K'ang-hsi hoped to avoid a third Albazin crisis. Vlasov learned of the Manchu departure in October 1687, and the new ambassador received a letter from Peking in January 1688 confirming the news. The military phase of the Amur confrontation between Russia and the Manchu Empire was now ended. It remained to seek a final solution at the peace table. The Russians claimed the Amur by right of colonization, a principle generally accepted in the West; the Manchus claimed it by virtue of their suzerainty over certain native tribes, a principle valid in the East Asian international system. Whereas the Ch'ing dynasty was prepared to grant Russia sufficient trading rights to take the persistent edge off Russian commercial hunger, it demanded in return Russian neutrality in Central Asia. Between the time of his appointment in 1686 and the opening of the Manchu-Russian conference at Nerchinsk in August 1689, Golovin received three sets of instructions. The ambassador was given maximal and minimal positions regarding the delimitation of the frontier. He was to begin by demanding that the Amur be made the border between the two empires. Yet if necessary, he was permitted to accept Albazin as the frontier, with the settlement remaining in Russian hands and the Russians retaining trading privileges throughout the Northern Manchurian river system.

The Manchu emperor issued his own instructions on May 30, 1688. According to them, Nerchinsk was the original camping-ground of the Mao-ming-an tribe, a Manchu tributary. Albazin was another tributary to the Ch'ing. Consequently, those areas were neither Russian nor uninhabited; they rightly belonged to the Manchus. The Amur River was even more important, however, than the immediate disposition of Nerchinsk and Albazin. As the upper and lower reaches of the Amur and all its tributaries were considered Manchu territory, "we cannot abandon them to Russia".

First, the Amur and its tributaries were of strategic importance to the Manchus because they constituted one great river system providing access directly into the heart of Manchuria to the south and the Pacific to the East.

The final delineation of the frontier was a compromise more favorable to the Manchus than to the Russians. As K'ang-hsi authorized in his second set of instructions to Songgotu, the Russians kept Nerchinsk, and the frontier was drawn between it and Albazin. The inclusion of a clause dealing with the handling of fugitives and criminals in the future implied that Sino-Russian contact would increase. The treaty also made careful provision for the conduct of trade, stipulating that either empire's subjects were permitted to cross the frontier and carry on commerce provided they held proper passports. This point was a Manchu concession to the Russian.

The frontier was delimited, and the problem of fugitives was settled, and the Russians were forced to withdraw from their advance positions. Manchu control of the Albazin region meant strategically that they controlled Russian access to the Amur River system. Nerchinsk became the chief emporium on the Russian side. The distance from Moscow to Peking was over 5,900 miles, and the trip there and back lasted no fewer than three years.

Almost simultaneous succession crises in the Ch'sing and Romanov dynasties increased the need for stability along the Sino-Russian frontier in the third decade of the eighteenth century. The new Ch'ing emperor, Yung-cheng, and the new tsarina, Catherine I, were both deeply involved in retaining their thrones and in achieving success on the international stage in those areas of primary importance to each: Yung-cheng in Central Asia and Catherine in Europe. In Russia Sava Vladislavich was named an ambassador on June 18, 1725. Vladislavich had some questions on frontier problems and insisted on meeting to conclude a frontier agreement at the Bura River near Selenginsk on June 14, 1727. The Manchu delegation to the frontier sessions of the Sino-Russian conference consisted of Tulishen, Tsereng, and Lungkodo.

On the day that he signed the frontier agreement, Vladislavich sent a report to the Senate and the College of Foreign Affairs giving his explanation of the agreement's speedy conclusion.

The Treaty of the Bura was a detailed description of the frontier agreed upon by the frontier commissions, but the line itself had to be drawn and marked with frontier stones to a greater degree of exactitude than was possible on paper, given the knowledge available to the negotiators. Joint Sino-Russian frontier survey commissions were therefore formed to define the frontier's precise location at all important points. The first commission completed its work on October 12, 1727, when it exchanged documents describing in detail the frontier between the Kyakhta and Shabindobagom rivers. The second commission exchanged protocols defining the frontier between the Kyakhta and Argun rivers on October 27.

Appended to each protocol was a register of the precise definitions of the boundary, area by area, and sixty-three "beacons" were set up as border stones at vital points, with a description of the border inscribed on each in Russian and Chinese. A neutral strip of land, "according to the comfort of local conditions", extended on either side of each marker. The way was now open for concluding the definitive Sino-Russian treaty itself, covering political and economic as well as frontier affairs

The Treaty of the Bura, the instrument that Peking required before it would sign any other agreements with Russia, was itself incorporated into the Treaty of Kyakhta. The Treaty of Kyakhta consisted of eleven articles, ranging over all aspects of the Sino-Russian relationship. Articles I and XI declared eternal peace and friendship between the two empires and discussed the language and ratification of the instrument. The other nine articles, constituting the Sino-Russian settlement itself, dealt with six specific problems: demarcation of the frontier (III, VII), exchange of fugitives (II), commercial relations (IV), a Russian religious establishment in Peking (V), forms of diplomatic intercourse (VI, IX), and settlement of future disputes (VIII, X). Article II delineated the entire frontier on the basis of the Treaty of the Bura, with the exception of the territory along the Ob River, east of the Gorbitsa, which according to agreement would be demarcated in the future "by ambassadors or by correspondence". The heart of the settlement was the commercial system, which according to the preamble to Article IV was specifically established in return for the frontier and fugitive settlements, that is, for Russian neutrality in Central Asia.

Two regular Sino-Russian frontier commercial emporia were to be crated, one at Kyakhta on the Selenga River, the other at a spot near Nerchinsk. Probably the most important element in the development of Sino-Russian stability was the "cultural neutrality" of the institutions of the Kyakhta treaty system. The Treaty of Kyakhta obviated the inevitability of conflict by creating institutions that in and of themselves lacked cultural implications and avoided precisely those forms of contact in which intellectual or institutional conflict had already taken place. Questions of titles and form were avoided by instituting correspondence between officials other than the tsar and the emperor. Russian caravans in Peking were not required to perform tribute ceremonials. The treaty itself provided specific punishments for certain crimes.

The Boarderland Establishment is Finalized - Treaty of Aigun of 1858.

We are following Sino-Soviet conflict over Amur border to the mid-nineteenth century, when the entry of Japan into contact with the outside world, the seeds of great change had been planted in East Asia, as Vasili Golovnin earlier in the century had suggested might happen.

In 1855, Putyatin was rewarded for his services in the mission of fixing the boundary between Russia and Japan by being made a count; three years later, he was given the navel rank of admiral. He would return to the Asian scene, for he had proved his diplomatic worth to the empire.

In 1858 Putyatin proceeded to send the Grand Council of Peking a supplementary statement proposing that the Amur and Ussuri rivers should constitute the boundary between Russia and China. This was an advance beyond anything the Russians had suggested before. The Manchu Courts stubbornly rejected the exigent requests of the "barbarian� envoys. In its replies, delivered at Shanghai, it directed that the British, French, and American representatives should undertake any negotiations with the Canton viceroy, while Russia should deal with the Amur commissioner. The Court also instructed I-shan to refuse Russia's request that the boundary be fixed on the Amur and Ussuri rivers.

The new Chihli viceroy, T'an T'ing-hsian, together with Ch'ung-lun and Wu-erh-kun-t'ai, in late April met with Putyatin at Taku, only to find that he still wanted to discuss the matters of boundaries and entry into Peking. The Court directed T'an to refuse the Russian demand for border demarcaition and to tell Putyatin, once more, to return to the Amur and negotiate there with I-shan, Amur commissioner, but Putyatin was already effectively negotiating the boundary question.

On the Amur, in the absence of Putyatin, I-shan in May of 1858 sent the assistant military governor, Chi-la-ming-a, to seen Muraviev, who assumed his powers in the field of foreign affairs in 1848, and urge him to discuss border matters. On My 23 and 24, Muraviev met with I-shan at Aigun. Muraviev proposed the signature of a new treaty fixing the Amur and Ussuri rivers as the common boundary between the two states. I-shan rejected the proposal, whereupon Muraviev withdrew from the conference in feigned anger, and Russian gunboats on the Amur cannonaded during the night. The following day I-shan sent a representative to mollify Muraviev to the end that he would resume negotiations. Muraviev graciously consented to return to the conference table, and on May 28, 1858, the two sides signed the Treaty of Aigun, by virtue of which the Amur River from the Argun to its mouth was accepted as the boundary between the two countries. Only vessels of the two countries might ply the Amur, Ussuri, and Sungari. The agreement provided further that, for the mutual friendship of the subjects of the two states, mutual trade of the subjects of both states was permitted along the three rivers. This gave the Russians the right of trade (and navigation) on the Sungari - a Chinese inland river. As for the region east of the Ussuri, it would remain under joint dominion of the two countries pending future determination of the common frontier in that region.

The established then border remained unchanged all the way into the 20th century, but it remained open for a dispute every time Sino-Soviet confrontations escalated.

The Sino-Soviet Amur conflict of 1960's (Khrushchev vs. Mao Tse-tung).

In 1960's the relationship between China and Russia was the most tense since the end of the 19th century. The major confrontation between Soviet Russia and Communist China had for some time been not in the Communist councils of the world, but in the Sino-Soviet borderlands. Two great nation-state, one Asian and the other Eurasian, faced each other in belligerent mood, as they had often done in the past along 4,500 miles of frontier.

Mao Tse-tung, in an interview of July 10 with a group of visiting Japanese Socialists, gave some confirmation of the scope of Chinese territorial desires. He said that, after World War II, the Soviet Union occupied "too many places", in Eastern Europe and in Northeast Asia as well. Moscow had brought Outer Mongolia under its rule, and Peking had raised this question with Khrushchev when he visited China in 1954, but he refused to discuss it. "Some people", Mao said, had suggested that Sinkiang should be included in the Soviet Union. "China has not yet asked the Soviet Union for an accounting about Vladivostok, Khabarovsk, Kamchatka, and other towns and regions east of Lake Baikal which became Russian territory about 100 years ago." He offered a sop to his visitors by voicing support for the return to Japan of "the northern islands" (the Kriles). Krushchev observed that Chinese emperors, as Russian tsars, had engaged in wars of conquest and voiced a warning: "The border of the Soviet Union are sacred, and he who dares to violate them will meet with a most decisive rebuff on the part of the peoples of the Soviet Union."

In May, 1966, foreign minister Ch'en yi reiterated the Maoist theme in an interview with a group of visiting Scandinavian journalists: the Russians, he said, were thieves who had annexed one and a half million kilometers of Chinese territory in the nineteenth century and even afterward. In October, as the Revolution swirled around the gates of the Soviet embassy in Peking, the Moscow press charged that Chinese troops had begun to fire indiscriminately at Russian ships plying the Amur, and Occidental correspondents in Moscow reported that, according to a Soviet source, organized Chinese "people's" movements in the Amur region and Sinkiang were calling for the return of "lost territories".

On March 2, 1969, Chinese and Soviet forces clashed on obscure Damanski (Chen Pao) Island in the Ussuri River, and the Soviets suffered thirty-four killed. Given the heavy Soviet casualties, and the circumstance that only a Soviet border patrol was involved, logic leads to the conclusion that, as charged by Moscow, China initiated the attack.

The Chinese claimed victory, but the evidence indicates that the Soviets brought up reinforcements and reoccupied the island. Then, in a note delivered to the Soviet embassy and published in Peking on March 13, the Chinese charged new Soviet aggressions in the disputed sector - as if building up a case. Soviet Defense Minister Lin Piao made a tour of inspection to the Damanski sector. On March 15, there was a new, and much bigger, armed clash on that battleground.

A diplomatic exchange followed. On the day after the clash, the Chinese Ministry for Foreign Affairs delivered a note to the Soviet embassy at Peking charging that a large number of Soviet forces accompanied by armored cars and tanks had penetrated Danamski Island "and the region west of that island". Chinese stated immediately that the Soviet government must bear the entire responsibility for all the grave consequences which could result from this.

The Soviet government on the same day addressed to the Chinese government a note which, referring to the clash, stated that this new provocation by the Chinese authorities is heavy with consequences. The message contained a plain warning: "the Soviet government declares that if new attempts are made to violate the integrity of Soviet territory, the Soviet Union and all its peoples will defend it resolutely and will oppose a crushing riposte to such violations."

No detailed report was made by either side. But what appears to have happened was that the Chinese had again attacked the Soviet position on Damanski Island. The Soviets effected a withdrawal, thus leading the Chinese to mass in the Damanski sector, whereupon the Soviets, who had anticipated the attack, opened up on the Chinese along a front several kilometers in length with artillery, missiles, tanks, and air power. Chinese lost 800 men as compared with about 60 Soviet dead. Soviet circles seemed assured that the "lesson" had gotten across to the Chinese.

On March 29, 1969, the Soviet government delivered the declaration to the Chinese embassy in Moscow regarding Sino-Soviet relations. The declaration began with a consideration of recent events on the Ussuri. It gave fewer details regarding the second clash than about the first. More significantly is stated with respect to the question of the Ussuri boundary that: "In 1861, the two sides signed a map on which the frontier line in the Ussuri region was traced. Near Damanski island, that line passes directly along the chinese shore of the river. The originals of those documents are held by the Chinese government as well as by that of the U.S.S.R.

When Moscow at the end of the declaration invited the government of the Chinese People's Republic to abstain from all action along the frontier that "would risk bringing about complications", and called upon Peking to resolve any differences "in calm and by means of negotiations", through the prompt resumption of the border negotiations undertaken at Peking in 1964, it was assured of an audience at the ninth congress. Symbolically, low-lying Damanski Island would about this time have been submerged by the spring floods on the

Peking in its April report to the congress acknowledged receipt of the Soviet offer and said that "our government is considering its reply to this".

On May 12, Peking announced that it had sent a message to the Soviet Union accepting in principle the Soviet proposal for resumption of the work of the mixed commission for the regulation of traffic on the border rivers and proposing that the date be fixed for mid-June. Moscow agreed, naming June 18 as the exact date. A few days after that exchange, on May 18, the Peking, as if to demonstrate that there had been no Chinese surrender, denounced the "new Soviet tsars" policy of naval expansion.

The Sino-Soviet frontier issue was still pending. The Chinese government complained that Soviet gunfire on the Ussuri had continued as an evident attempt to force negotiations, but in the end it agreed in principle to the Soviet proposal, suggesting that the date and place of the projected negotiations regarding the Sino-Soviet frontier be discussed and decided by the two parties through the diplomatic channel.

On July 8, shortly after the prognostication of war, the Chinese charged that the Soviets had violated chinese territory by intruding into Goldinski (Pacha) Island in the Amur near Khabarovsk. Moscow described the incident as a Chinese violation of the existing frontier and charged that the Chinese had staged a "malicious provocation" with the aim of sabotaging the Khabarovsk talks. In an address of July 10, Soviet Foreign Minister voiced a warning to China : "We rebuffed and we shall rebuff all the attempts to speak with the Soviet Union in terms of threats or, moreover, weapons. What happened in March of this year near Damansky Island on the Ussuri River must make certain people consider more soberly the consequences of their actions"(New York Times, July, 1969).

The next development seemed to bear out the Moscow charge that the Goldinski Island clash was a "provocation" designed to abort the river-navigation negotiations. The Chinese delegation at Khabarovsk on July 12 broke off the talks. But on the following day the delegation reversed itself and informed the Soviet side that, contrary to its statement of July 12, it has decided to remain in Khabarovsk and agreed to the continuation of the commission's work. Interestingly enough, nothing more was heard of the Goldinski incident.

An agreement was signed at the Khabarovsk conference to govern navigation of the border rivers in the current year, and provision was made for holding further talks regarding the matter in 1970.

On October 7, 1969, it was officially announced by Peking that there is no reason whatsoever for China and the Soviet Union to fight a war over the boundary question. The Chinese government, the statement said, had "never" demanded the return of territory annexed by tsarist Russia "by means of the unequal treaties", and had "always" stood for the settlement of existing boundary questions in "earnest all-round negotiations". The provisions of the "unequal treaties" of the nineteenth century were not the prime issue at the negotiation of 1970.

The shattered Chinese leadership was undertaking the long, arduous road toward adjusting to the world, instead of remaking it immediately in Maolist design. In accordance with the principle of peaceful coexistence, it had at last manifested a readiness to accept a measure of reconciliation with Moscow.

5. Discourse and Status

6. Forum and Scope

The Russia-China Friendship and Cooperation Treaty:

The motivations behind this new treaty are much more complex and involve serious geopolitical, military, and economic considerations. In a sense, this treaty is a logical product of the improvement in Sino-Russian relations that began under the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, and continued under Boris Yeltsin.

The 2001 Russia-China treaty, which covers five important areas of cooperation:

Joint actions to offset a perceived U.S. hegemonism;

Demarcation of the two countries' long-disputed 4,300 km border;

Arms sales and technology transfers

Energy and raw materials supply

Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO)

2001 On June 14, Russia, China, and four Central Asian states announced the creation of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), an arrangement ostensibly aimed at confronting Islamic radical fundamentalism and promoting economic development. Together, the agreements portend an important evolving geopolitical transformation for Russia and China, two regional giants who are positioning themselves to define the rules under which the United States, the European Union, Iran, and Turkey will be allowed to participate in the strategically important Central Asian region. (http://www.heritage.org/Research/RussiaandEurasia/BG1459.cfm)

APEC

September 12, 1999, in Auckland, New Zealand, President Jiang Zemin met with Russian Prime Minister Putin on the sidelines of the Informal Leadership meeting of APEC. Putin expressed the willingness to expand economic cooperation and trade between the two countries and reiterated Russia's consistent one-China stand on the Taiwan question.

There are also numerous meetings and letters exchanged between these two countries.(http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjb/zzjg/dozys/gjlb/3220/t16725.htm)

7. Decision Breadth

The Influence of U.S

The desire to counter U.S. global supremacy and the West's pressure on both countries regarding the rights of independence-seeking ethnic minorities (and human rights in general) furnished much of the impetus for a friendship treaty between Russia and China as well as the creation of the so-called Shanghai-6 Organization (SCO). The parties of this organization vehemently oppose the policy of NATO-led "humanitarian interventions," such as the Kosovo war, which was not sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council.

Chairman Jiang has repeatedly declared that "hegemonism and power politics" are the "main source of threat to world peace and stability" as well as China's interests. Beijing is clearly interested in curtailing the U.S.-led condemnations and sanctions of China for human rights, as in the aftermath of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre. Furthermore, Russia and China are both seeking to safeguard their status as two of the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council. Finally, they are working to boost each other's military potential as well as that of other countries that pursue anti-American foreign policies, such as Iran and Iraq.

8. Legal Standing

I. A General Survey of the Treaties Concluded between China and other countries

In the year of 2000, China concluded some 330 state and governmental bilateral treaties and agreements (or other instruments with full features of treaties) with other countries , more important among which were 222 economic and trade treaties (and exchange of notes), 22 financial treaties, 26 political treaties, 10 consular treaties, 9 legal agreements and agreements covering the fields of culture, health, science and technology, communications and post and telecommunications; China also concluded 6 multilateral treaties with other countries (for details, please refer to the attached table). Besides, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, with authorization of the Central Government, concluded 10 bilateral agreements with foreign countries.

II. A General Survey of China's Cleaning Up of Treaties Concluded with Other Countries

The cleaning up of treaties is to confirm, revise or terminate the validity of the treaties signed between states, based on the theory of the international law , particularly the theory of the treaty law and in view of the actual situation of the state. Starting from 1991, China has been systematically cleaning up the treaties. Up to the present, China has done the relevant work with 10 countries such as Germany, Czech, Slovenia and Russia. This work is of positive significance in clarifying the validity of the treaties, resolving the state of uncertainty of the validity of the treaties and promoting the development of relations between China and the relevant countries.

Continent: Asia

Region: East Asia

Country: China

< src="images/blueline.gif">

The Amur river is one of the largest rivers in North East Asia. In the world's rating,

it occupies the 9 th place on length, 4444 kilomiters and the 10 th on basin's area,

1,85 million square kilometers. It is formed as a result of Shilka and Argun rivers j

unction on the territory of Chitinskaya oblast. The largest objects of the basin are:

rivers Zeya, Bureya, Sungari, Ussury, Amgun, Khanka lake.

Spatially the basin is situated on the territories of three countries - Russia (53%

of basin's area), China, Mongolia (47%). From this point of view Amur has transboundary

and international significance.

More than 75 million people live in Amur river's basin, more than 90%

of the population accounts to China.

It predetermines difficulties in establishing of coordinating regulations for protection

and usage of water, biological and other resources, not to mention the projects of economic development.

IV. Environment and Conflict Overlap

Information sources

Website:

http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjb/zzjg/tyfls/tyfl/2626/t15460.htm

http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjb/zzjg/tyfls/tyfl/2626/t15464.htm

Data Resources:

http://www.adm.khv.ru/invest2.nsf/pages/ftradechar_en.htm

http://trade.russiansoft.com/index.php?chapter=1000projects®ion_id=30

http://www.slavweb.com/eng/Russia/feast-e.html

http://tpspb.frinet.org/links/business

http://tpspb.frinet.org/links/business.asp

http://www.adm.khv.ru/Invest2.nsf/folders/General-en.htm

http://www.lars2.org/unedited_papers/unedited_paper/Slynko%20Amur.pdf

http://www.arabicnews.com/

http://www.adm.khv.ru/invest2.nsf/pages/common/amur_en.htm

http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/200212/03/eng20021203_107822.shtml