|

ICE Case Studies |

The Angkor Empire, Environment, and Conflict By Udom Hong |

I. Case Background

|

![]()

Deep within the jungles of central Cambodia lie the ancient ruins of Angkor, evidence of a civilization that centuries ago stretched its borders across most of Southeast Asia. Today, the influence of the Khmer, or Angkor, Empire remains scattered throughout the region in the form of ancient temples, monuments, and statues. Amidst a devastating war in the 1960s-70s that transformed the landscape and population, the Angkorean ruins in the area, for the most part, remain unchanged and still hide clues about the once prosperous civilization. A review of literature on the Khmer Empire hints at a rise and decline similar to the infamous Roman and Mayan civilizations. Though, what conditions led to the downfall of the Khmer Empire? Many scholars have postulated that the growth of agriculture and the acquisition of fertile soil required to cultivate crops was the largest factor that drove conflict and helped to contribute to the significant decline of this once ancient Empire. Concordantly, there is some evidence that a major climate shift that occurred in the 1300s or early 1400s may have also contributed to changing the dominant authoritarian rule in the region.

“It is grander than anything left to us by Greece or Rome. At a first sight one is most impressed with the magnitude, minute detail, high finish and elegant proportions of this temple, and then to the bewildered beholder arise mysterious afterthoughts—who built it? When was it built? And where now are the descendants of those who built it? It is doubtful if these questions will ever be satisfactorily answered. There exist no credible traditions—all is absurd fable or extravagant legend.”

--Frank Vincent, Jr.[1]

|

The dawn of the Angkorean Empire dates as far back as 802 AD, when a ruler, King Jayavarman II, established an area (currently known as Siem Reap), as the capital to be called Angkor. Just north of the largest lake in the region, the Tonle Sap, the area provided a central location for the expansion of the empire and helped ensure the foundation for an agricultural sector that would supply the surrounding area for centuries to come. Prior to this regional establishment, the area was under the influence of Indian culture for a number of centuries[2], and it is believed that no true concept of Cambodia existed until the Angkorean Empire began to unify peoples of local tribes and towns into a cohesive society, as evidenced in ancient stone inscriptions that functioned as their system of writing.[3] Though, once established by Jayavarman II, it set forth a centuries-long line of monarchs that has helped define what Cambodia is today.

|

Southeast Asia circa the 1200s |

The discovery of the ruins by European explorers, in the mid-1800s, brought forth renewed interest in its historic past. Often compared to ancient Roman, Mayan, and even Egyptian civilizations for its grandeur and mysticism, the weathered, yet long-standing, structures of Angkor that remain continue to hold mysteries to archeologists and historians.

With this mandate from the ruling authority to build structures to accommodate the forthcoming expansion of this empire, in the 9th century, the inhabitants of the region created a vast city that is estimated to have extended 1000 square kilometers with an assortment of nearly 1000 temples, gates, and pools.[4] Subsequent rulers over the next 400-500 years continued to have shrines and temples constructed during their reigns.The purpose of building the grandiose temples monuments was to pay homage to the great devarajas – god-kings or rulers. Functioning both as a place of worship during the monarch’s reign and as a mausoleum after their passing, the central temples were symbolic centers for the major cities.[5]

As at least one million inhabitants were living within the ancient city’s

boundaries, the cultivation of the land surrounding land for agricultural use

was undoubtedly a large task.[6] “At its peak, some 50 million rice paddies

stretched through 12.3 million acres of land,” writes Coates.[7] Forest related

resources, including such items, as elephants, ivory, feathers, spices, and

woods, became major components in trade for the Khmer with their Indian and

Chinese neighbors.[8]

Thus, as seen in the history of other ancient civilizations, we also encounter

conflicts that can arise over resources and trade. Klare notes, for example,

a timeless resource that has caused discontent among nation-states is the use

and management of water systems.[9] Likewise, minerals and timber resources are

also commodities that have created conflicts among nations. In the case of the

Angkor Empire, the civilization had to contend with border tensions on all sides.

Most notably, the Bagan and Sukhothai Empires, to the West, and Champa Empire to the East, pressed the Angkoreans to increase their own territorial limits. The people of the Champa Empire, the Chams, were mostly comprised of descendants with a Malayo-Polynesian heritage, which was occupying an area resembling southern Vietnam, today. The Chams and Khmers, interacted very frequently in peaceful trading of resources and also in conflicts in the 12th and 13th centuries.[10] The Bagan (today, known as Burma) and Sukhothai (known as Thailand, now) Empires also proved to be formidable opponents for the ancient Angkoreans during their dominant reign of the region.

|

Some scholars have noted that a need to sustain a relatively large population

was a major factor in driving the expansion. Specifically, as evidenced by the

number of rice paddies and acres of land required, linking conflict to the allocation

and distribution of resources could be a valid reason for why the ancient Angkor

peoples may have sought to have extended its influence to encompass much of

the Southeast Asian peninsula. With advances from the Bagan and Champas Empires,

repeated skirmishes with the Khmers, ultimately weakened the Angkorean state

and led to its’ gradual decline in the mid-1400s.[11]

The pattern of how inhabitants settle, in any empire, is also a major indicator

in how long a civilization might persist. Coe notes that the similarities with

the Mayan settlement patterns could help explain the structure of social, economical,

and political systems. He writes, “the classic Khmer settlement pattern…consisted

of a large rural population scattered in villages throughout Cambodia, supporting

ceremonial centers with rice and corvée labor.”[12] Indeed, the laborers

and farmers who supported and ensured the wealth and power of the royalty class

in the region in return received “considerable material security and the

protection of a patron to whom they owed allegiance.”[13] The hierarchy structure

that was implemented illustrates the demanding labor tasks and near poverty

like conditions for the common people, while the theocratic population governed

the affairs of the Empire. “Through a strong bureaucratic system operating

from the provincial capitals, all of Cambodia was organized into a kind of machine

for the support by rice and corvée labor of the cult centers…it

may have been that rare phenomenon, a truly pyramidal society,” comments

Coe.[14] Though, as the Empire grew, Lockhard noted that the rulers of Angkor were

too ambitious in their expansion and that the “administrative rigidity”

may have factored into the growing number of challenges as time went on.[15]

|

|

|

Perhaps, the most detrimental problem that led the Empire’s decline was

a shift in the climate of the Southeast Asian region. With the increasing production

and trade of agricultural products, the need for irrigation systems in the area

was, presumably, a necessary task to continue growth. Scholars seem to agree

that the Angkorean system of irrigation pathways and reservoirs was very intricate

and unique in its scale when compared to the surrounding nation-states. At its

peak efficiency, the original hydraulic systems around Angkor Wat began to gradually

divert valuable nutrients to neighboring cities that had more advanced hydraulic

infrastructure. B.P. Groslier suggests that the irrigation systems may have

become stagnant in certain areas, which could have led to an increase infectious

disease outbreak, such as malaria.[16] Similarly, the heavy reliance on irrigation

systems for agricultural production may have been a detriment to the Angkor

Empire as shifts in monsoon patterns in the 14th or 15th century disrupted normal

water management systems.[17] “The close relationship between water management,

priesthood, and temple foundations that characterized Angkor somewhat resembles

the social organizations of ancient Egypt and is similar also to the Maya civilization

of medieval Guatemala,” notes Chandler.[18]

|

Cambodia in 2006 |

802 AD to 1432 AD

Continent: Asia

Region: Southeast Asia

Country: Cambodia

Khmer Empire (Cambodia)

Champa Empire (Vietnam)

Bagan Empire (Burma)

Sukhothai Kingdom (Thailand)

![]()

Loss of Habitat [HABIT]

While it was centuries of conflict with neighboring kingdoms that eventually

drove the Khmer Empire into decline, the root cause of the fall of this ancient

civilization can be attributed to a gradual degradation in forest, water, and

soil resources.[19] Under an array of changing rulers, the Empire’s extension

of its borders across most of Southeast Asia was, perhaps, enhanced by the desire

to increase agricultural production at the cost of the delicate ecology of the

region.

As the expansion policy continued forward, many of the Angkorean temples were in the process of construction, and massive irrigation projects altered the landscape drastically to accommodate sustaining agricultural and infrastructure systems for more that two million Khmers. The collection, processing, and manufacturing of woods, stones, and metals to build these structures were brought in from local quarries and jungles.[20] Roland Fletcher noted that aside from the depletion of woods for farmlands, timber was used to construct houses, temples, cooking products, and even the scaffolding for the larger projects.[21] This rapid transformation of the landscape illustrates the close relationship between human growth and the raw materials in their environment.

|

Of particular focus for many archeologists and historians is the connection in fertility of soil to irrigation systems. Failures in the waterways could have played a large part in the conditions of farmlands and agricultural products.[22] The Angkor region, in particular, is known for experiencing six months of drought, followed by six months of rain annually. Utilizing satellite technology, the topography of the region has been studied and reveals growth patterns in vegetation that indicate where canals and reservoirs did exist.[23] Surveys in the area have indicted that as many as four large reservoirs were constructed to retain water in the months of drought. Groslier hypothesized that the Angkoreans created a type of “hydraulic city” comprised of canals and these reservoirs that allowed for rice crops to be planted several times a year increasing surplus crops and providing sufficient sustenance for the laborers and artisans involved in construction of the temples.[24] Though, because it is thought that the reservoirs and irrigation canals delicately linked, the efficiently of dispersing silt into the farmlands and keeping the soil fertile could have been easily disrupted and broken down the ecological balance and led the empire towards a gradual decline.

Some scholars have recently proposed, however, that an abnormal climate change event might have possibly occurred in the SE Asia region centuries ago. Fletcher’s studies have suggested that a medieval warm period shifted to a cooling age where the efficiency of the irrigation systems was so damaged that the Khmers, perhaps, abandoned the Angkor region altogether. In fact, a recent IPCC report suggests that methane emissions from rice fields can alter climate conditions significantly.[25] If a similar occurrence occurred centuries ago with the agricultural lands in Southeast Asia, it is possible that monsoon patterns may have been disrupted increasing the likelihood of water droughts, famine, and a rise in infectious diseases.

The climate of the region is generally warm all year with a combination of a six-month dry season marked with frequent droughts, and an intense rainy monsoon season. Temperatures average about 80-85° F, with average rainfall heaviest in the summer and fall seasons.

(1) Nation A impacts Nation A: Khmer and Khmer.

![]()

In the span of roughly six centuries (800-1400), the Khmer empire expanded its empire to reach nearly all of Southeast Asia, and simultaneously saw the rise and development of a rich and mysterious culture that remains evident only in the temples and shrines in the Angkor region. From the years 802 to 1432, a number of rulers guided the empire through prosperity and hardships. Centuries of conflict with the Chams, and the Bagans and subsequently, the Sukhothai gradually deteriorated the strength and power of the Khmer empire by around the year 1430. It is believed that a factor leading up to conflicts can be attributed to the production of agricultural crops and the land used to cultivate it, though combinations of political, social, and religious strife have been noted as well. Aside from the “unsustainable drain of resources of the empire”, as Tully notes, the empire “also sustained vast numbers of unproductive people, including aristocrats and Brahman priests, members of the religious order and the royal family itself.”[26] The largest challenge to the Khmer hegemony came from the Thais as they launched a formidable offensive in 1431 sacking Angkor, moving Khmers to work as slaves for them and perhaps, interfering with the irrigation systems.[27]

[Interstate – High]

Because of the lack of written records, it is still difficult to ascertain the fatality level of conflicts. Most resources for this case study have speculated that while the disputes may have begun as small local issues, escalating violence grew to the point where the latter rulers of the Khmer empire built up an army strong enough to withstand many major assaults on the territory.

|

![]()

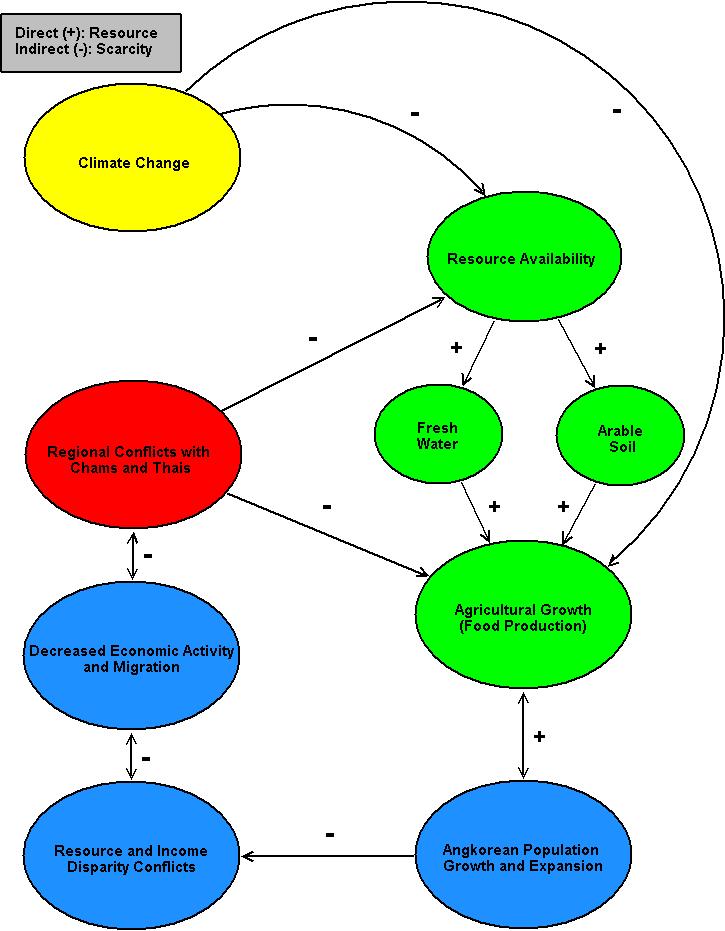

The link between environment and conflict is complex. Similar to Longeran’s model, this causal diagram illustrates the various links that tie environment and conflict in the context of the decline of the Angkor Empire.[28] The role of climate change as an indirect factor in disrupting resource availability and agricultural cycles is a large component in determining what may have happened to the inhabitants of the Angkor region. Conversely, the connections between resources, agricultural growth and population growth are directly related and highlight the rapid expansion of the Empire via their temples and irrigation systems. Failures in any of the water management processes, may have led to indirect societal, economic, and political conflicts, further fueling regional disputes.

|

[Regional]

[Yield]

Retrospectively, the rise and decline of the Angkor Empire has illustrated the perils of unprecedented expansion at the cost of natural resources. With constant pressure from the Chams, Bagans, and Thais, the ancient Khmer were forced to cede their power and leave the Angkor area to the care of nature. Time has withered away much of what can tell historians how this society functioned for so many centuries. Today though, as the country recovers from a regional war in the 1970s that now challenges government leaders and development specialists, the remnants of this old and mystical civilization continue on as evident in the temples and monuments that are left standing within the jungles of this country.

A recent New York Times article notes that the Southeast Asian region

is presented with a challenging dilemma, as news of oil reserves have been discovered

near southwestern Cambodia.[29] As climate change becomes increasingly debated in

policy and science discourse, this news of a new supply of fossil fuel resources

in the area shall renew possible conflict and highlight challenges in sustaining

the environment. This case study can, perhaps, highlight the dangers of progress

that government leaders may not consider in relevant issues today.

• The Mayans, Climate Change, and Conflict: maya.htm

• Khmer Rouge and Wood Exports: khmer.htm

• Mekong River Dam: http://www.american.edu/ted/mekong.htm

• The Mongol Invasion of Japan – The "Divine Wind" Case:

divine-wind.htm

• Teak Trade: teak.htm

• Rwanda and Conflict: rwanda.htm

Endnotes:

[1] Frank Vincent Jr., "The Wonderful Ruins of Cambodia," Journal of the American Geographical Society of New York 10 (1878). 234.

[2] David P. Chandler, A History of Cambodia, 2nd ed. (Boulder, CO ; North Sydney, NSW, Australia: Westview Press ; Allen & Unwin, 1992). 12.

[3] John A. Tully, A Short History of Cambodia : From Empire to Survival, Short History of Asia Series (Crows Nest, N.S.W.: Allen & Unwin, 2005). 15.

[4] Karen J. Coates, Cambodia Now : Life in the Wake of War (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2005). 51.

[5] Lawrence Palmer Briggs, "A Sketch of Cambodian History," The Far Eastern Quarterly 6, no. 4 (1947). 351.

[6] Tully, A Short History of Cambodia : From Empire to Survival. 17.

[7] Coates, Cambodia Now : Life in the Wake of War. 51.

[8] Chandler, A History of Cambodia. 14.

[9] Michael T. Klare, Resource Wars : The New Landscape of Global Conflict, 1st ed. (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2001). 138.

[10] Chandler, A History of Cambodia. 14.

[11] Jared M. Diamond, Collapse : How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed (New York: Viking, 2005). 14.

[12] Michael D. Coe, "The Khmer Settlement Pattern: A Possible Analogy with That of the Maya," American Antiquity 22, no. 4 (1957). 410.

[13] Craig A. Lockhard, "Integrating Southeast Asia in the Framework of World History: The Period before 1500," The History Teacher 29, no. 1 (1995). 19.

[14] Michael D. Coe, "Social Typology and the Tropical Forest Civilizations," Comparative Studies in Society and History 4, no. 1 (1961). 73.

[15] Lockhard, "Integrating Southeast Asia in the Framework of World History: The Period before 1500." 20.

[16] Chandler, A History of Cambodia. 53.

[17] Roland Fletcher, Damian Evans, and Ian J. Tapley, "Airsar's Contribution to Understanding the Angkor World Heritage Site, Cambodia - Objectives and Preliminary Findings from an Examination of Pacrim2 Datasets," (Greater Angkor Project, 2002).

[18] Chandler, A History of Cambodia. 53.

[19] Tully, A Short History of Cambodia : From Empire to Survival. 17.

[20] Vincent Jr., "The Wonderful Ruins of Cambodia." 235.

[21] Tully, A Short History of Cambodia : From Empire to Survival. 53.

[22] Coates, Cambodia Now : Life in the Wake of War. 53.

[23] Jamie James, "Shuttle Radar Maps Ancient Angkor," Science 267, no. 5200 (1995). 965.

[24] Tully, A Short History of Cambodia : From Empire to Survival. 44.

[25] "Asian Rice Emits Greenhouse Gas," CNN, http://edition.cnn.com/2007/WORLD/asiapcf/05/01/climate.rice.ap/index.html.

[26] Tully, A Short History of Cambodia : From Empire to Survival. 29.

[28] Steve Longeran, "Environmental Change and Regional Security in Southeast Asia," (Ottawa, Canada: Directorate of Strategic Analysis, Operational Research and Analysis, Department of Defence Canada, 1994). 7.

[29] Seth Mydans, "Big Oil in Tiny Cambodia: The Burden of New Wealth," New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/05/world/asia/05cambo.html.

Works Cited:

"Asian Rice Emits Greenhouse Gas." CNN, http://edition.cnn.com/2007/WORLD/asiapcf/05/01/climate.rice.ap/index.html.

Briggs, Lawrence Palmer. "A Sketch of Cambodian History." The Far Eastern Quarterly 6, no. 4 (1947): 345-63.

Chandler, David P. A History of Cambodia. 2nd ed. Boulder, CO ; North Sydney, NSW, Australia: Westview Press ; Allen & Unwin, 1992.

Coates, Karen J. Cambodia Now : Life in the Wake of War. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2005.

Coe, Michael D. "Social Typology and the Tropical Forest Civilizations." Comparative Studies in Society and History 4, no. 1 (1961): 65.

———. "The Khmer Settlement Pattern: A Possible Analogy with That of the Maya." American Antiquity 22, no. 4 (1957): 409-10.

Diamond, Jared M. Collapse : How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. New York: Viking, 2005.

Fletcher, Roland, Damian Evans, and Ian J. Tapley. "Airsar's Contribution to Understanding the Angkor World Heritage Site, Cambodia - Objectives and Preliminary Findings from an Examination of Pacrim2 Datasets." Greater Angkor Project, 2002.

James, Jamie. "Shuttle Radar Maps Ancient Angkor." Science 267, no. 5200 (1995): 965.

Klare, Michael T. Resource Wars : The New Landscape of Global Conflict. 1st ed. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2001.

Lockhard, Craig A. "Integrating Southeast Asia in the Framework of World History: The Period before 1500." The History Teacher 29, no. 1 (1995): 7-35.

Longeran, Steve. "Environmental Change and Regional Security in Southeast Asia." Ottawa, Canada: Directorate of Strategic Analysis, Operational Research and Analysis, Department of Defence Canada, 1994.

Mydans, Seth. "Big Oil in Tiny Cambodia: The Burden of New Wealth." New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/05/world/asia/05cambo.html.

Tully, John A. A Short History of Cambodia : From Empire to Survival, Short History of Asia Series. Crows Nest, N.S.W.: Allen & Unwin, 2005.

Vincent Jr., Frank. "The Wonderful Ruins of Cambodia." Journal of the American Geographical Society of New York 10 (1878): 229-52.

Image Credits:

All graphics and/or images obtained under public domain from Wikipedia Commons and CIA World Factbook.