| ICE Case Studies

|

The Weathering of the Armada by Cerena V. Mitchell | I.

Case Background |

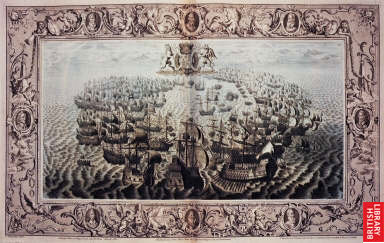

At a time of powerful nations and even more powerful monarchs, Philip II of Spain and Elizabeth I of England, warring against one another, were creating one of the largest conflicts to date. The development of this hostile relationship was lengthy and bitter involving both personal and political entanglements, bringing them to battle. An integral part of the conflict was the "Invincible" Spanish Armada, Spain's secret weapon to rule the world. However, through a series of fateful natural occurrences, the Armada suffered a decisive loss from the British navy in 1588. One of the key factors contributing to this demise of the world's greatest fleet was the weather that plagued the Armada. The tides and the winds wreaked havoc on the ships' paths and Spain's plan of victory. At each turn of the battle, the ships were seemingly marked to not make it back to the nation the sun never set on.

©Library of Congress

The Powerful Monarchs: Elizabeth I of England and Philip II of Spain

At the time of the Armada's launch, Spain was perhaps the most powerful nation in the world. The country controlled all the known Americas, except Brazil, Portugal, a greater part of Italy, and the Low Countries (seventeen separate provinces, which now are comprised of Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands). Philip II, ruler of the Spanish empire, was also the titular King of England because of his marriage to Elizabeth I's sister, Mary I. This made for extremely tense relations between the nations because of the differences in religion. Spain was a devoutly Catholic nation while England was a newly reformed Protestant one. This would play an integral role in the launch of the Armada.

The war had been stirred by Elizabeth's greatest weapon: Sir Francis Drake. Drake was a heady pirate, infamous for his captures on the seven seas in the name of Her Majesty. In 1581, the Low Countries had begun to revolt against Spanish domination led by the Dutch William of Orange. William had written several treatises against Philip, decrying him a murderer and adulterer in his notorious 1580 Apologia. (1) Catholics were depicted as immoral people with a similar king. To counteract, a Catholic assassinated William in 1584. England allied with the Dutch nations to halt the Catholic domination; Philip commanded the seizure of British ships as retribution. Elizabeth then ordered Drake to wreak havoc upon the Spanish colonies in the Caribbean. However, this was giving England an image of a "nation of pirates". (2)

With each step, war was becoming imminent. A final blow was the elimination of the last potential Catholic ruler in England. Philip had intentionally married Mary I in 1554 to cement not only Spain as the powerful nation, but also what the country stood for: catholicism. Philip himself was a devout Catholic, even building his palace El Escorial with complete simplicity and his own bedroom looking directly down unto the main altar. Mary was much more pious than Philip, and in the midst of the horrific Spanish Inquisition, she thrived. Philip was known to try to calm her efforts against the Protestant faith brought on by her father, Henry VIII, but to no avail. Mary died in 1558 without a producing the "link" that Philip had wanted to fully bind the two nations. Philip then went on to try and win Elizabeth's affections, but the Virgin Queen rebuffed his offers. Philip was humiliated and later that year wed 14-year-old Elizabeth of Valois, the daughter of the French king, thus effectively allying Spain with the French against the British.

Finally in 1587, word reached Spain that Elizabeth had executed the one hope for a Catholic England: Mary Queen of Scots. With this event, all of Philip's dreams and plans for a Catholic Europe were smashed. He immediately sent word to ready the Armada for war.

The Spanish Armada was thought to be invincible. The boats were built for battle as well: they were purposely built higher and taller than other ships of the day so as to give the soldiers more leverage when fighting in hand-to-hand combat. The Spanish did not construct their boats to outmaneuver or to to be light; the bigger boats gave more room for sword fights. The Armada did not come equipped with the number of guns the English ones did. The English ships carried 11.5 guns on average while the Spanish carried 9. (3) Unlike the Spanish, the English did not want to come close to their enemies while on the seas; they preferred guns and long-ranged weapons. The English relied on low built ships for ease and speed on the water.(4) In a time of sailing vessels, if the winds were not favorable, the mission could be potentially disastrous. The key differences in design between the ships will cause a decisive victory.

The men called to arms were both military and civilian personnel. To Philip, this was a war primarily over religion. He asked the sailors to not swear and also enlisted 200 priests to accompany the men for their spiritual needs. (5) Abroad the 130 Armada ships, there were over 30,000 men while the English held about half that figure:

| Soldiers | Sailors | Rowers | Others | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish | 18,973 |

8,050 |

2,088 |

1,545 |

30,656 |

| English | 1,540 |

14,385 |

- |

- |

15,925 |

Philip called for the fleet to leave from Lisbon, Portugal on May 28, 1588. The fleet was lead by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, a man who never went out to sea and had no prior expertise in commanding such a fleet. However, he was extremely wealthy and loyal to the crown, two favors the king had hoped to exploit. (7) Immediately the ships experienced delays and setbacks: there were poor winds and extremely slow progress. Relying on winds to give the Armada a sound push into the English Channel, the boats instead floundered and wasted 13 days to get there. (8) The stormy seas were an ill omen from the beginning, causing damage to the boats.

On July 31, 1588, the first contact between the English and Spanish ships occurred. The Armada ships at this time had already been battered along the Spanish coast, creating additional distress and problems within the fleet. Also, food was a major concern. At a time of no refrigeration and during a tense war, any extra unaccounted for time dented the supplies and possibly could make for starved soldiers. Despite having any advantage at this point over the English, the Spanish ships were able to somewhat evade the cannons to move across the Channel. The English had seen some tides against them at Plymouth, but with their smaller and lighter craft they were able to maneuver through the rough spots. (9) The Spanish, in the heavier laden ships, kept wanting to draw the English in for close battle to utilize their skills in hand-to-hand combat. However, the English stayed a distance, firing cannons whenever the chance allowed.

In this first encounter, Drake, leading the English fleet, was able to surprise the Spaniards in his attack direction. Medina Sidonia was immediately on the defensive and had to stand ground without being able to move up the Channel. Due to the English surprise tactics, the Spanish fleet quickly lost any sense of order as as tate of confusion laid in. Two ships, the Rosario and the San Juan were injured by fellow ships, while one of the largest ships, the San Salvador, exploded due to a rebellion on board. (10) Faced with more internal errors then any caused by the British, the Armada needed a new course of action.

The Duke of Medina Sidonia, plagued with English cannons firing on his Armada and not being able to counter with any true force, decided to land at Calais. The winds and tides were assisting the ships to land there, and this was the original point of rendezvous for the militia and the fleet. Originally, Philip had ordered the Duke of Parma, a well-known military hero of the age, to lead the troops he was commanding out of the Low Countries to Calais to meet with the Armada. Parma's men had been fighting the rebellions in those regions, and were to board the Armada, and then land in England. The militia consisted of around 60,000 infantry and cavalry. (11)

By the time of the arrival at Calais, the Spanish had suffered immense losses strategically. The numbers were not so diminished as the fact that the English had humiliated the "Invincible" Armada. However, Drake was aware that the tides might turn in Spain's favor once Medina Sidonia and Parma were to reunite. Ammunition would be replenished as would supplies and men. On July 27, 1588, the Armada landed in the safety of the Calais harbor. However, despite several messages and waiting, Parma and his reinforcements had not been heard or seen. The Armada had little time to restock with the English nipping at their heels. Finally word came that Parma was no where near meeting Medina Sidonia nor would he be able to. The Armada was stuck: no where to go with the English so close and now no supplies. As if things could not be any bleaker, the next day, two things occurred: the weather and tides changed creating an almost impossible obstacle to getting the Armada out of the inlet and the English sent fireships to attack the Armada.

With no place to go because of the weather, the Armada had no choice but to attempt to defend the fleet. The Armada was all in a panic, with ships darting everywhere to escape the danger of the deadly fireships. Ironically, not one of the fireships actually touched a Spanish one, but the effect was just the same. The Armada was never able to recover the order it held before. (12) The ships were on the run, but with the weather and tides against them, they had nowhere to turn. The winds would not let them head back down the English Channel to head straight home to Spain. It was decided to take the only other option: to go around England through the North Sea and down by Ireland to return home. This would prove far more deadly than the battles with the English.

Even if the ships escaped from Drake's grasp to head home around Scotland and Ireland, there had been a strict order put into place by Elizabeth. If any British subject spotted a Spanish ship or sailor, they were to shoot. There was to be absolutely no abetting the sailors whatsoever. Like Spain and the Low Countries, England had been experiencing rebellion in Ireland and Scotland; there would heavy punishments if these Catholic regions aided their religious counterparts. So, with the weather against the Armada, even if they managed to flee the storm and to crash, no one was legally allowed to help them.

The waters battered the ships along the North Sea causing duress and a loss of supplies. However, the worst was around the Irish coast. Having been at sea much longer than expected without rejoining with Parma's supplies, the Armada was in dire straits. There was a minimum of foodstuffs abroad and disease was rampant. With the weather against the sailors, they encountered setbacks not initially factored in. At this last leg of the journey, the captains only wanted to get their ships back to Spain to allow for rest and rebuilding. The route needed to be as short and quick as possible to save time and food. This would prove to be tragic.

Due to a lack of accurate maps and nautical drawings, the more than half the ships ran aground off the coast of Ireland. The weather kept pushing the ships into the legs of Ireland, and the captains let it. They took the beating not knowing how precariously close they were to the shore and rocks until it was too late. (13) The winds were pushing the ships to the limit and in the end the ships were not able to make it because of a lack of knowledge and just fatigue. Finally, the straggling fleet of the once powerful Armada landed in September 1588 in Santander, Spain. The ships were badly damaged, as were the men abroad.

The impact of the defeat was immediate: England was now the most powerful nation. No longer did Spain rule the seas. However, historians argue that really this defeat was only the beginning of the end for the Spanish. After this defeat, the Spaniards made better boats, like the English ones, which were lighter and more agile, so as to handle better in rough weather. More treasure ships than ever before were reaching Spain's shores from the American colonies and beyond. (14) There were two more Armadas built that Philip sent to capture England, both defeated in the end.

With the great effect the weather played in the role of the Armada's demise, there are many "what ifs" that arise. The winds and weather had basically already beaten the Armada before any English ship was sighted. Just think, would we all be speaking Spanish now and eating paella?

The conflict between England and Spain had been ongoing and without an official declaration date at the demise of the Armada; however, open hostility began in 1585 and the defeat was in 1588.

Continent: Europe; Ocean: Atlantic; Region: English Channel

© CIA

The Armada experienced disaster from immediately off the harbor of Lisbon, Portugal. As the fleet traveled up through the Bay of Biscay, they were again troubled by poor tides and winds, as well as the English pursuing them. As the ships reached the English Channel, the Duke decided it would be best to await reinforcements at Calais. Because of extremely poor weather conditions against the Spanish Armada, most chose to return home by going around the United Kingdom and Ireland. Due to poor maps at the time, captains misread exactly how far Ireland jutted out, which ended in extensive shipwrecks in this region.

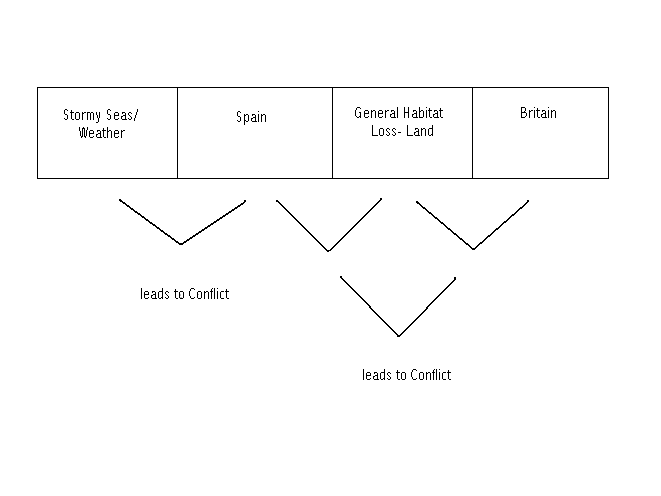

General Habitat Loss, i.e. war between England and Spain over land

With a war between the nations, the victor could presumably take over the defeated nation causing a massive loss of land for the natives. The way of life and culture could have been drastically undermined and changed. For example, if Spain had beaten the English, the English might have been forced to convert to Catholicism and perhaps speak in Castilian. This dramatic shift would have resulted in the loss of a cultural habitat for the English people.

Ocean- Atlantic Ocean, specifically the English Channel

This area is extremely temperate with hot summers and cold winters. The temperature ranges from the 50s to the 70s °F during the timeframe of the Armada attacks.

Act Site- English Channel

Harm Site- Spain and England

Example- Land disputes

War

High

Class |

Number |

|---|---|

Galleons |

4 |

Flag- and vice-flagships of auxiliary warships |

8 |

Other auxiliary warships |

10 |

Hulks |

11 |

Small craft |

15 |

Galleasses |

2 |

Galley |

1 |

TOTAL |

51 |

As for the actual casualties of the Spanish people, historians speculate the figure to be between 10,185 to 20,000. (16)

Looking back at the table of the people involved in the battle, with a ratio of almost two-to-one for soldier to sailor, one could venture to say that there were between 5,000 and 10,000 civilian deaths.

Direct- the weather caused intense problems for the Spanish Armada

Causal Diagram

Bilateral- England and Spain

Victory for England

Although the English "won", scholars argue that this was really the beginning for the Spanish Armada. There were in fact several fleets over the years, and each fleet was an improvement upon the last. The loss for Spain only encouraged and fostered better designs for better ships. The next Armada was styled after English ships, which were built to handle any type of weather. This acceptance of defeat shows the Spaniards' willingness to try again and to make the Armada truly "Invincible".

The following cases are most like the Armada one in that the weather creates the conflict. For the Armada case specifically, there was preexisting a conflict between England and Spain. Through this conflict, the weather conflict "stormed up". (Pun intended.) The stormy seas caused immense damage and was the ultimate source of conflict for the Spanish.

Guano - the story of a natural fertilizer causing a conflict between nations; most like the Armada's defeat, guano's existence is threatened by adverse weather conditions such as El Nino

Boerwar - a war beginning as a conflict over a natural resource, gold, between the British and the Boers of South Africa

Aegean - the dispute between Turkey and Greece over the continental shelf is creating disastrous consequences for the natural habitat there

Chiapas - the uprising in Chiapas as a direct result of the signing of NAFTA

Tupac - the revolt in Peru demanding the freeing of Tupac Amaru prisoners

Cancod - the effect of lowering allowable "catches" of cod in the world on the waters surrounding Canada

Japanoil - the results on the environment when an oil tanker sinks

Shrimp - the effects of shrimping on the sea turtle population

Ukcod - similar to Cancod, the effect of changing fishing quotas

Jellywax - the Lebenase importation of Italian waste

NOAA's Case Studies of Oil Spills - oil spills are another source of environmental conflict stemming from the heavy reliance upon predictable weather conditions for a safe delivery

Library of Congress - a great source for all research pertaining to this case

(1) Williams, Mark. The Story of Spain. Malaga, Spain: Santana Books, 2000. 126.

(2) Graham, Winston. The Spanish Armadas. New York: Doubleday and Company, 1972. 51.

(3) Lewis, Michael. The Spanish Armada. New York: Thomas Crowell Company, 1968. 78.

(4) The Spanish Armada. Dir. Ruth Wood. Videocassette. Maday Entertainment Group, 1997.

(5) Williams, Mark. The Story of Spain. Malaga, Spain: Santana Books, 2000. 126.

(6) Lewis, Michael. The Spanish Armada. New York: Thomas Crowell Company, 1968. 81.

(7) Fernandez- Armesto, Felipe. The Spanish Armada. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. 103.

(8) The Spanish Armada. Dir. Ruth Wood. Videocassette. Maday Entertainment Group, 1997.

(9) The Spanish Armada. Dir. Ruth Wood. Videocassette. Maday Entertainment Group, 1997.

(10) Lewis, Michael. The Spanish Armada. New York: Thomas Crowell Company, 1968. 116.

(11) Lewis, Michael. The Spanish Armada. New York: Thomas Crowell Company, 1968. 85.

(12) Lewis, Michael. The Spanish Armada. New York: Thomas Crowell Company, 1968. 154.

(13) Fallon, Niall. The Armada in Ireland. Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1978.

(14) Williams, Mark. The Story of Spain. Malaga, Spain: Santana Books, 2000. 127.

(15) Lewis, Michael. The Spanish Armada. New York: Thomas Crowell Company, 1968. 208.

(16) Lewis, Michael. The Spanish Armada. New York: Thomas Crowell Company, 1968. 208-209.

The three images of the Armada are used with permission from the British Library. Thanks!!

August 2005