| ICE Case Studies

|

|

I.

Case Background |

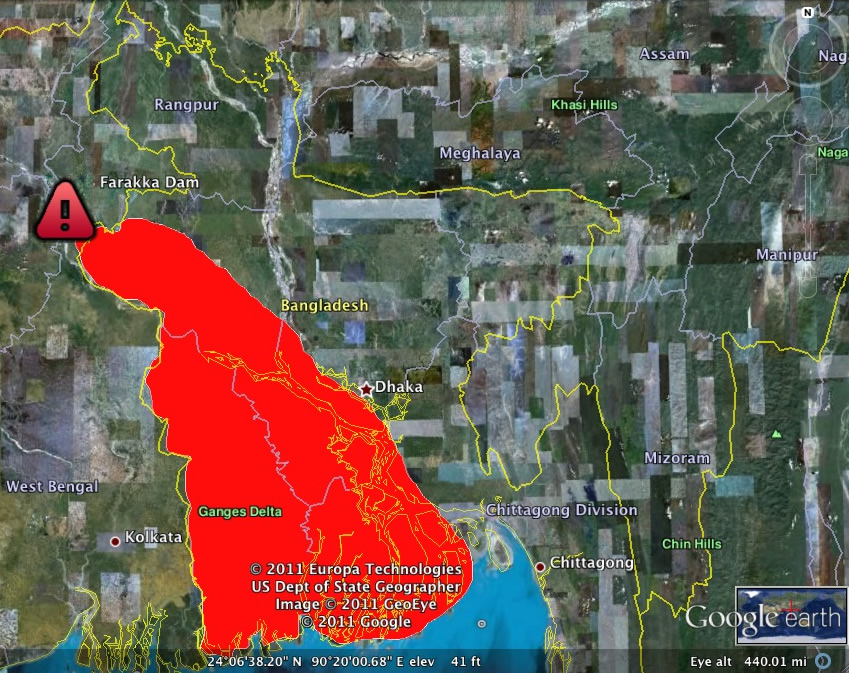

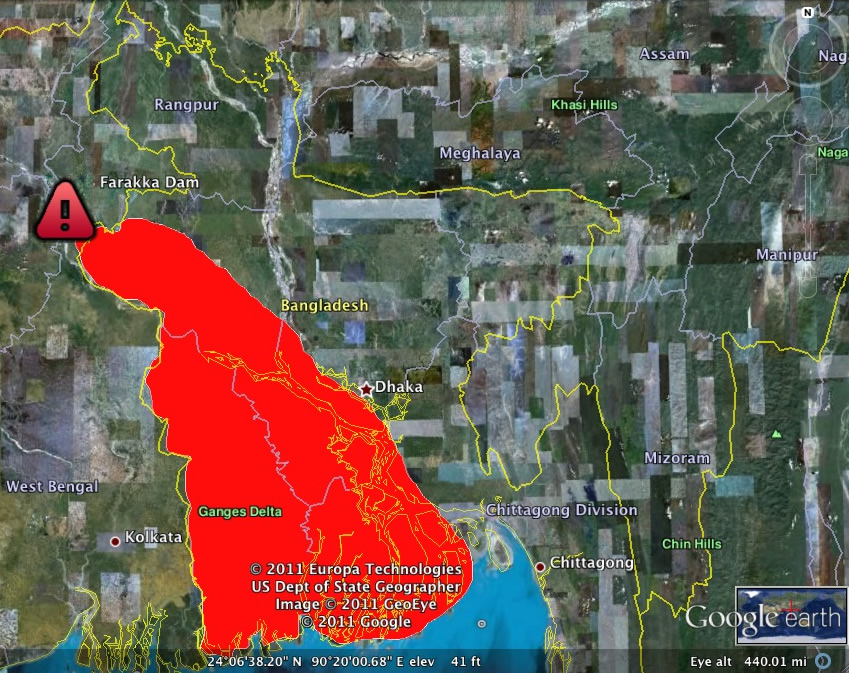

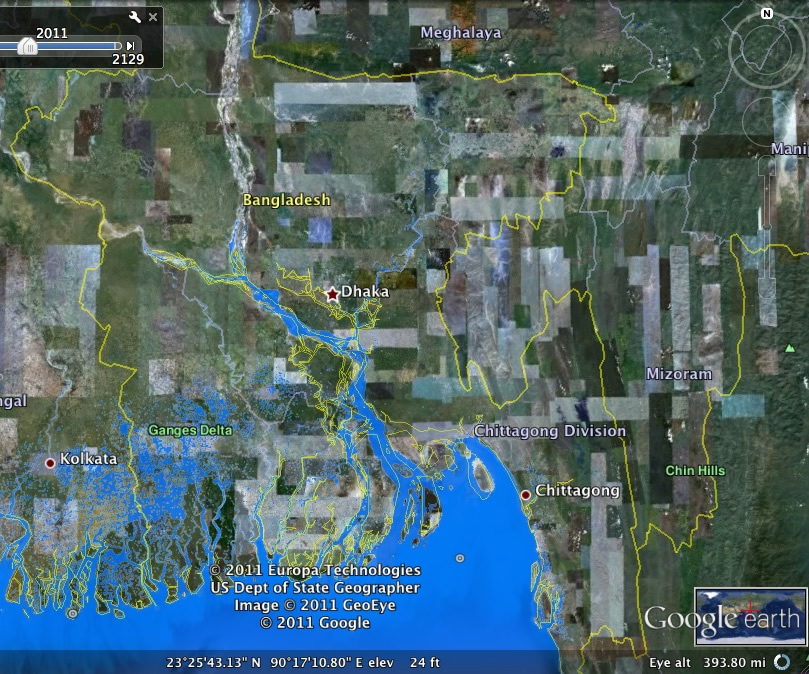

Fig.1 Interactive Google map of Bangladesh and Assam

View Larger Map

Climate change alters habitats so that the carrying

capacity of lands can no longer maintain the indigenous population.

Bangladesh is currently experiencing this change, forcing locals to

migrate to resource-rich locations. Unfortunately, there are few

unsettled locales left on earth, so these migrants inevitably come into

contact with local populations. If resources are strained already, new

additions to the community are generally unwelcome. Dissimilar cultural

and religious beliefs exacerbate enmity between the groups, as they fear

the dissolution of their identities. This is what Assam and various

populations around the world are currently experiencing. (Swain 1996)

Bangladesh encompasses the Ganges-Jamuna-Meghna delta, one of the great river deltas of the world, so floods are a common occurrence, but their severity and timing are becoming increasingly unpredictable. Recent floods have affected more than two-thirds of the total area of Bangladesh, causing irreparable damage to crops, houses, roads, embankments, cattle, poultry, fishery and all other types of economic infrastructure (Islam 1992). This phenomenon is exacerbated by the construction of massive dams and irrigation systems by the Indian government and a propensity for major natural disasters in Bangladesh. The combination of economic, social, institutional and political factors, as well as consecutive onslaughts of natural disasters forces environmental refugees to migrate to urban slums, disease-ridden refugee camps targeted by dangerous militias, or outside of Bangladesh. (Islam 1992)

One migration site in particular is the Assam region of India. Here, there have been many clashes between the indigenous (mostly Hindu) populations and the Bangladeshi migrants (mainly Muslim). The indigenous population fears for the loss of culture and identity in their homeland, resulting is severe violence between the groups. Some extremist groups, such as the National Democratic Front of the Bodoland (NDFB), have threated the complete ethnic cleansing of all migrants threatening their way of life in Assam. The Indian government is attempting to secure its borders to avoid future collisions, but does so through equally violent means.

Violent conflict in Assam between indigenous groups and Bangladeshi migrants began in 1979 when the presence of 70,000 immigrants was discovered in one constituency. When the government did nothing to mitigate this influx of outsiders, the groups polarized and organized. The result was at least 4,700 deaths that year. From that point on, an unstable government has endured constant civil disobedience campaigns and excessive ethnic violence.

Climate change is increasing instances and levels of

major floods in Bangladesh. The effects are magnified by the

construction of dams along major waterways. Most Bangladeshis live along

rivers or maintain livelihoods that depend upon them. Flooding is

destroying their homes and livelihoods, forcing them to leave their

homes in search of viable living situations. Bangladeshi environmental

refugees are relocating to various nearby countries, in particular the

Assam region of India, where there have been violent clashes with

indigenous populations. (Swain 1996)

Given the human tendency to group with like individuals for protection, there are many conflicting Assamese and migrant Bangladeshi groups in Assam (Swain 1996). The NDFB is a major extremist group pressing for complete ethnic cleansing of Muslim migrants.The introduction of the massive Bengladeshi population added to already strained relations between ethnic Bodos affiliated with the NDFB and the government of Assam. The group’s most vital goal is to separate completely from Assam and create their own state of the Bodoland, located in the northwest region of the Indian state of Assam (World Bank 2008). The United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA) is a second insurgent group with the primary goal of maintaining Assamese societies and traditions against the encroaching Bengalis. This group is also centered in the Assam state of northeastern India. The ULFA has been engaged in violent disputes for the longest of the three groups discussed here. It is also the most deadly, having accumulated at least 25,000 casualties over time. The Dima Halam Daogah/Black Widow faction (DHD‐BW) is the most recent radical group to arise against Bangladeshi settlers. DHD-BW operates in northeast Assam in the Dimaraji territory and is comprised of the Dimasa tribal group (World Bank 2008).

Support for radicalism increases with added strain

on jobs and resources. Government officials in India are wary of unrest

and are actively trying to stem the influx of migrants and negotiate an

end to overt violence. Bangladeshi environmental refugees are searching

for sustainable livelihoods in Assam, but the government fights

migration, lacking effective mechanisms for integration with local

communities.

Video of flooding in Bangladesh

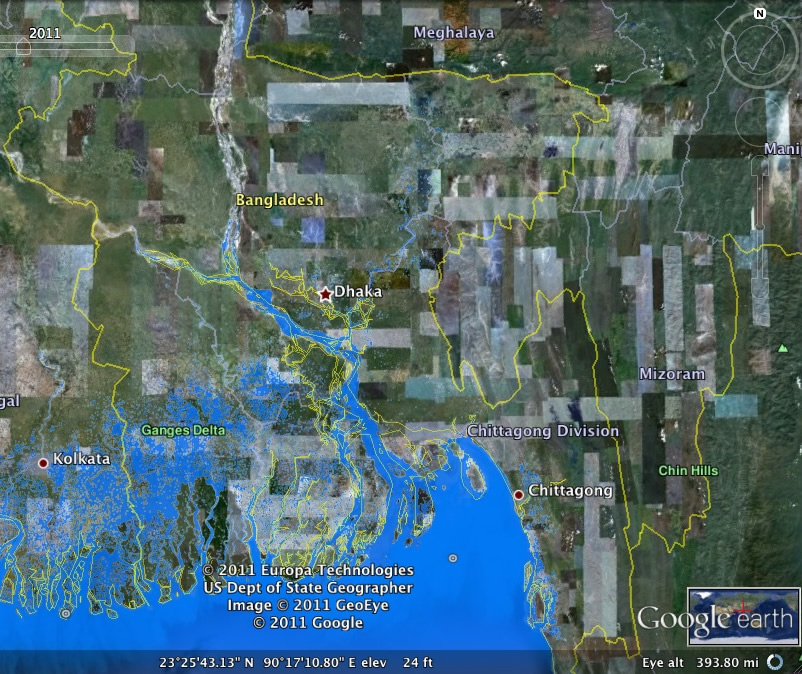

Fig. 2: Area of Farakka Dam's Influence in Bangladesh. Source: Swain 1996

Increased flooding and its consequences that are caused by climate change are creating many issues for this low-altitude country, which depends largely on riverine areas to maintain individual livelihoods. A good portion of this flooding arises from unexpected torrential monsoons. Brian Fagan explains that drastic changes in monsoon paths and intensities can be caused by minor changes in sea surface temperatures. As our earth warms up due to man-made climate change, these storms will continue to worsen. (Fagan 2008)

Silting has increased alarmingly in all of Bangladesh's rivers due vastly increased amounts of it carried by river water from upper-riparian countries and catchment areas within Bangladesh, which has only been exacerbated by the construction of the Farakka Dam in the upstream of the river Ganges near the Indo-Bangladesh border. The dam dries up riverbeds during six or seven months of the year, reducing the dry-season flow of the river system to southern Bangladesh. (Islam 1992) The Dam disrupts the entire ecology of the Delta, which disrupts fishing and navigation and inundates nutrient rich soil with salt deposits, impairing Bangladesh’s agricultural and industrial production (Swain 1996). See figure 2 to the right for a visual representation of the vast influence the Farakka Dam has on rivers, lands, and livelihoods in Bangladesh.

Erosion is also a major issue in Bangladesh due to its loose soil. This only increases with more severe flooding and altered water flows involved with climate change. Habitable, arable land and consequently livelihoods are increasingly stolen from settlers due to massive erosion coupled with population growth. (Islam 1992)

Bangladesh is a quite disaster-prone, mainly riverine country comprised of more than 700 rivers, about 3,000 tributaries and canals. Strong currents during the summer and rainy seasons combined with the zigzag courses and the alluvial nature of the soil in the delta regions produce serious erosion of riverbanks. (Islam 1992) Low categories of land are waterlogged for most parts of the year. Even the medium-low categories of land suffer from waterlogging after the rainy season, especially after the floods and tidal surges. (Islam 1992)

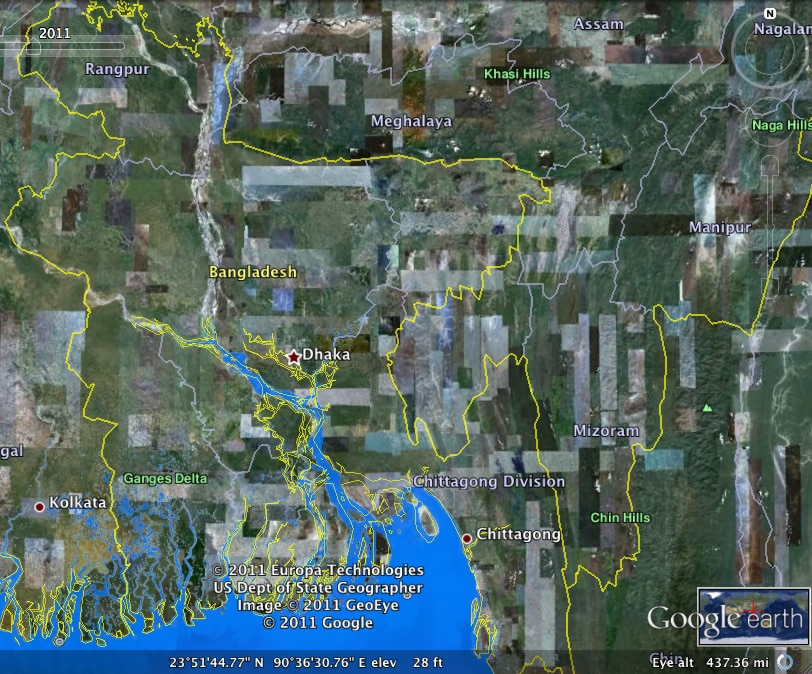

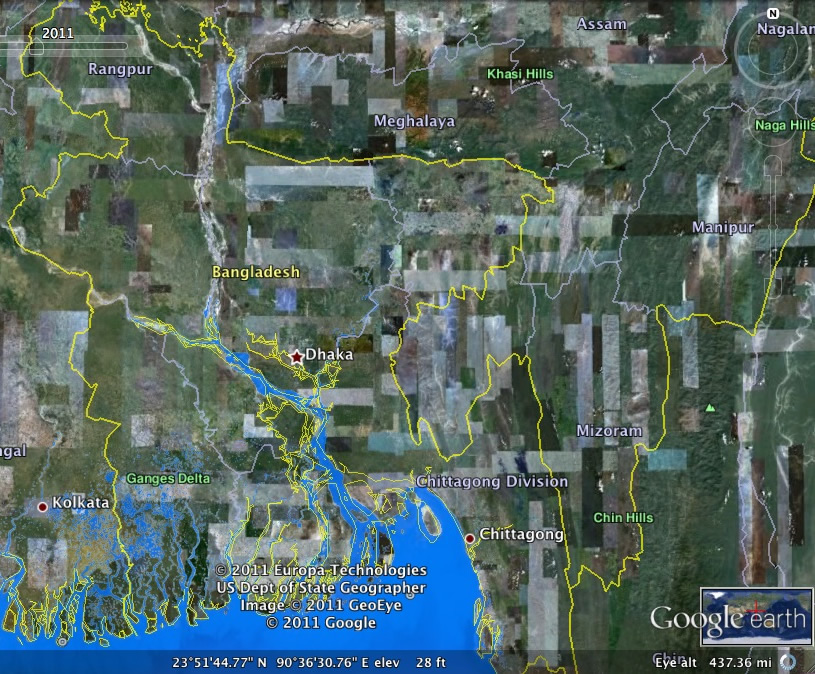

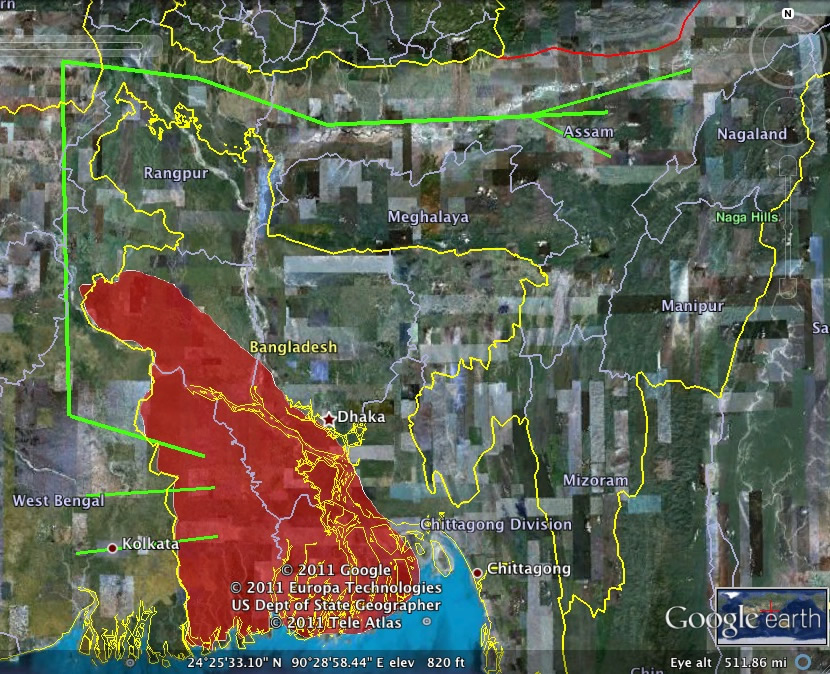

More than half of Bangladesh lies less than 5 m above sea level, drastically multiplying the dangerous affects of flooding and sea level rise as seen in Figures 3-6. Some forecasts predict that sea level will rise one meter by 2050 and three meters by 2100, the affects of which can be seen in the figures below. Keep in mind that these same predictions include a 100% increase in population by 2050 as well, adding to the perilous situation. (Myers 1993)

Fig. 3: 1 Meter Rise in Sea Level

Fig. 4: 2 Meter Rise in Sea Level

Fig. 5: 3 Meter Rise in Sea Level

Fig. 6: 4 Meter Rise in Sea Level

The actions causing climate change occur north of the populations affected in Bangladesh. India erected the Farakka Dam just outside of Bangladesh and increases in precipitation can also be traced from India. The disastrous affects are felt most in Southwest Bangladesh. Citizens are forced to migrate almost 700 miles out of southwest Bangladesh to Assam as shown in green in Fig. 7 below. India offers a higher standard of living for the disenfranchised refugees. Because Bangladesh and West Bengal share a common ethnicity, border security tends to be less strict in the Southwest and the citizens do not understand the concept of the nation-state exactly. Most consider the entire Ganges-Brahmaputra region “greater Bengal,” instilling in them a sense of rightful claim to those lands (Homer-Dixon 1994). Some Bangladeshi refugees decided to settle in nearby West Bengal, but the area is also experiencing some of the same degradation as their homelands, so most preferred to make the long trek to Assam.

Fig.7: Path of an Environmental Refugee. Source: Swain 1996

There are multiple facets to this conflict. This

study focuses on the main intrastate violent conflict between

Bangladeshi migrants and indigenous Assamese, but the groups also have a

history of contention that adds to the negative perception of the

other. While under British colonialism, outsider Hindus from Calcutta

ruled Assam, much to the chagrin of locals. Britain also deemed Bengali

the official language of Assam at this time. These scars make the

Assamese especially cautious of losing the political and cultural

control of their state. (Homer-Dixon 1994)

Indo-Bangladesh relations worsened in March 1972 after adoption of the

politically controversial Indo-Bangladesh Trade Pact. They continued to

stratify over the maritime belt dispute, Indian support for the

pro-Mujib guerrillas, the sharing of Ganges waters, and control of

disputed borderlands. Bangladeshis feel that India exploits it in an

effort to dominate, which was heightened when India constructed the

Farakka Dam in West Bengal merely 11 miles east of the Bangladesh

border. As discussed above, this dam magnifies the damaging effects of

climate change and is perceived as stealing resources from Bangladesh.

(Hossain 1981)

There is also a clash between the cultures and

religions of these groups as Bangladeshis are mainly Muslim and Assamese

mainly Hindu. The indigenous groups fear the loss of their identity

through dilution of their culture by the influx of outsiders. Extremist

groups, such as the NDFB, base persecution of refugees on what is termed

‘nativism,’ which occurs when a group claims "rights upon land,

employment, political power and cultural hegemony that are greater than

those people who are not indigenous” due to historical claims (Swain

1996). On the other hand, Bangladeshis can also claim this right because

they also have ancestors that once settled in the area.

Conflict in Assam began in the late 1970s when a

routine pre-election census in Mangaldoi revealed the presence of 70,000

Bangladeshi nationals. The incumbent Congress Party needed the

migrants’ votes to win power, so they did not actively attempt to deport

them. Angry Assamese watching their resources dwindle and their

identity disappear saw this inaction as complete government failure.

Battles quickly erupted between native Assamese, led by the All Assam

Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP) and All Assam Student's Union (AASU), and

Bangladeshi settlers, who also organized in the face of certain

aggression. The violence cost more than 3,000 lives, culminating in a

systematic attack on the Bangladeshi Muslim migrant village of Nellie by

more than 8,000 native Hindu Assamese. That five-hour rampage cost over

1,700 lives. Attacks between the groups continue to this day and are

intensifying with calls for ethnic cleansing by extremists. (Swain 1996)

The Indian government, in at attempt to keep these

shameful acts out of the public eye, has not accurately recorded the

actual number of fatalities, but the World Bank reports that at least

30,797 casualties from this conflict (World Bank 1991-2008).This number

increases greatly when deaths occurring in the course of border crossing

are included.

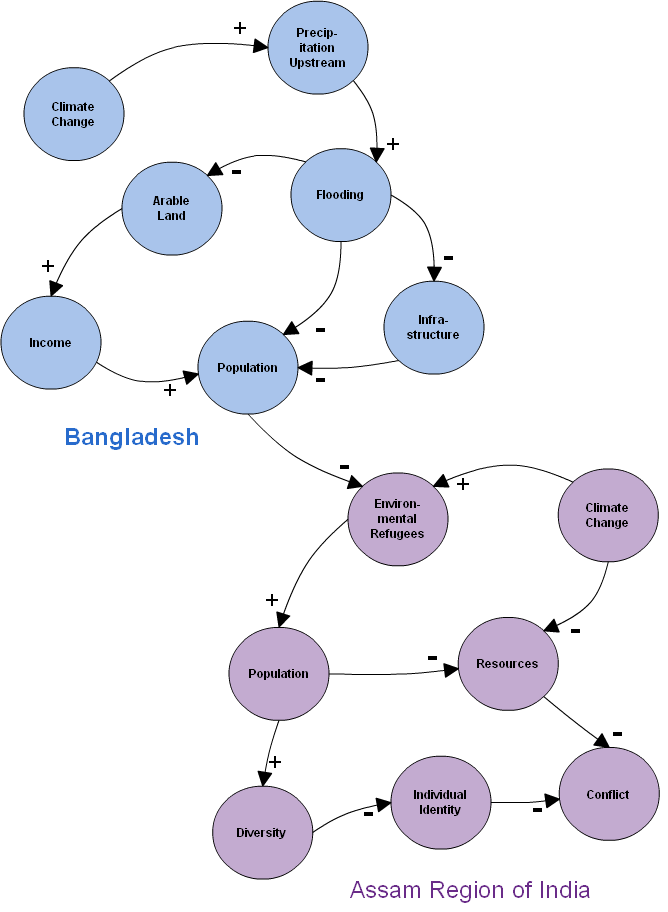

Fig.8: Causal Loop Diagram between Environment and Conflict

In Bangladesh (blue), as Climate Change intensifies, there is an increase in precipitation upstream from Bangladesh. This increase causes an increase in flooding along the rivers in Bangladesh. Flooding forces people that previously lived along rivers to find a new place to live, hence population decreases. Flooding also causes salinization of the land, making it more difficult to maintain agriculture and irrigation. Being a riverine country, citizens’ livelihoods rely on agriculture around rivers; therefore less arable land means less income. If people cannot make a living in the area, they must move, hence the decrease in population. Flooding also destroys planned and standing infrastructure, forcing people to move to areas that can provide the services they need.

Climate change has caused an increase in the amount

of environmental refugees that are settling in the Assam region of India

(purple). The increase in population also decreases the amount of

resources available per capita. Inevitably, as more people are vying for

the same resources, there will be conflict. Also, the increase in

population is due to a group of environmental refugees that are of a

completely different culture, heritage, and religion than the indigenous

population. From perspectives of the people, an increase in diversity

threatens the strength of the identity of both groups, which increases

conflict as they fight to maintain their culture.

Government officials searching for the extra votes of migrants overlook the massive migration and do not pursue deportation. Now, the strain of population growth is being felt throughout India, forcing officials to secure borders. (Swain 1996)

The conflict also benefits extremist groups that have historically pursued secession from India into their own state. The strain of the amount of illegal migrants in Assam has created enmity in a greater portion of the population. This increased polarization provides higher membership for groups with a radical and violent vision of “cleansing” their country of foreigners. With increased membership, comes increasing resources and subsequently power to enact deadly campaigns.

Growing power and threats from Hindu organizations led to massive deportation of the Bangladeshi Muslim migrants in 1992. Unfortunately, Bangladesh did not want them either, as the Foreign Minister of Bangladesh made clear when he refused to accept them without documented proof of Bangladeshi citizenship, halting the deportation process. (Swain 1996)

Some of the extremist groups have agreed to

negotiations, resulting in temporary ceasefires, but the conflict

continues to threaten the lives of migrants in Assam (World Bank 2008).

The levels of violence have caused the government of India to call for

increased border protection to stem the flow of illegal immigrants. This

only increases casualties as Indian border security forces (BSF) are

being issued orders to shoot individuals on site that attempt to enter

India illegally. The government claims to be protecting citizens from

terrorist movements and thieves that crossover between borders to steal

livestock, but has no way to distinguish between criminals and refugees.

(Hossain 1981)

Korfamin This case deals with famine in Korea from the damaging effects of severe weather caused by climate change.

vineland.htm This case handles the migration of Vikings to North America c.1,000 AD made possible by a warming climate, which led to beneficial trade, but also war.

Indobang This case talks about the water dispute between India and Bangladesh.

Sudan.htm This cases focuses on intrastate conflict in Sudan and asks if it is caused by religious clashes or resource availability.

Kikuyu.htm This case deals with the forced migration of the Kikuyus and the environmental degradation it caused.

Jordan This study blames a lack of water resources for the 1967 Arab-Israeli War and other regional disputes.

Bates, Diane C., Environmental Refugees? Classifying

Human Migrations Caused by Environmental Change, Population and

Environment, Human Sciences Press, Inc., Vol. 23, No. 5, May 2002. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27503806

Buhaug, Halvard, Nils Petter Gleditsch, and Ole Magnus Theisen,

Implications of Climate Change for Armed Conflict, To be presented to

the World Bank workshop on

Social Dimensions of Climate Change, 25 February 2008.

DARA, Climate Vulnerability Monitor 2010: State of the climate. < http://daraint.org/climate-vulnerability-monitor/climate-vulnerability-monitor-2010/>

Fagan, Brian. The Great Warming: Climate Change and the Rise and Fall of Civilizations. Bloomsbury Press, New York, NY. 2008.

Gleditsch, Nils Petter, Ragnhild Nord s, and Idean Salehyan. Climate Change and Conflict: The Migration Link. International Peace Academy, May 2007.

Homer-Dixon, Thomas. Environmental Scarcities and Violent Conflict. International Security. The MIT Press, Vol. 19, No. 1, Summer 1994, pp. 5-40 http://www.jstor.org/stable/2539147

Hossain, Ishtiaq. Bangladesh-India Relations: Issues and Problems. University of California Press. Asian Survey, Vol. XXI, No. 11, November 1981. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2643997

Islam, Muinul. Natural Calamities and Environmental Refugees in Bangladesh. Refuge, Vol. 12, No. 1 (June 1992).

Myers, Norman. Environmental Refugees in a Globally Warmed World: Estimating the scope of what could well become a prominent international phenomenon. BioScience Vol. 43 No. 11, December 1993).

Swain, Ashok. Displacing the Conflict: Environmental Destruction in Bangladesh and Ethnic Conflict in India. Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 189-204, 1996. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42543

World Bank. Violent Conflict Dataset. 1991-2008. http://go.worldbank.org/IY3XIPSSZ0

December 2011