|

|---|

Source: Worldpress |

1. Abstract

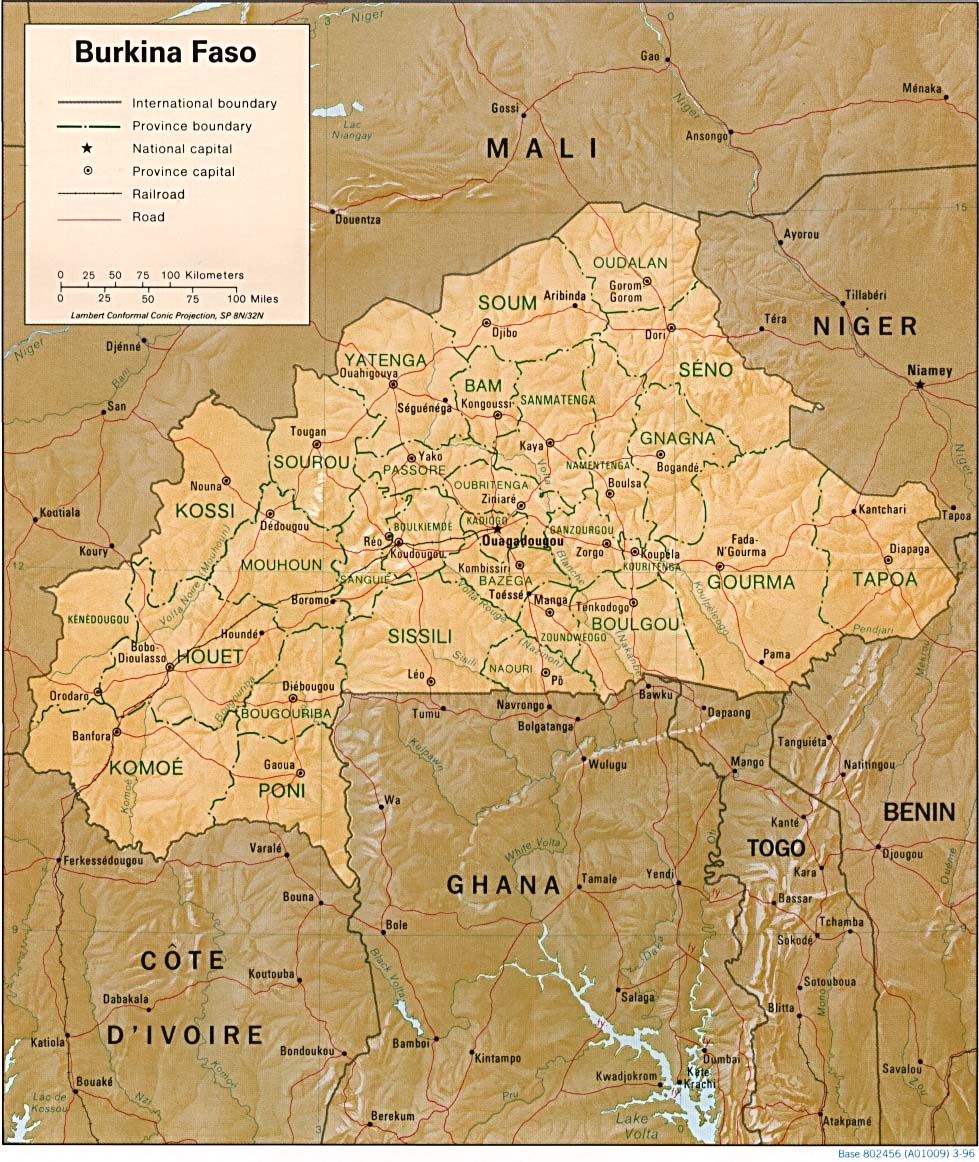

A landlocked West African country, Burkina Faso, has been ill-fated by political instability, military coups and lack of inherited resources. Situated in the semi-arid region of the Sahel, the 4th poorest country in the world today faces constant drought periods and is heavily dependent on food aid.

After numerous military coups, President Blaise Compaore, came in power in 1987 and restructured the country s economy to attract foreign investment and focus heavily on cotton industry to boost growth. During the 1990s, massive investment on cotton industry boosted cotton production to cater to the country's economic growth. The incentives for the subsistence farmers to be labors or producer of cotton become more favorable. In a country, where agriculture sector holds the biggest share in its economy, a drastic shift in land use pattern is noticeable to favor this cash crop.

As the cotton industry, parastatal Sofitex, was privatized in the 1990s to boost cotton production in limited arable land, the dependency on imported food increased further. This creates a new player in the already vulnerable nation - food security. In 2008, during doubling of world food prices, Burkina Faso witnessed a violent food riot in its capital with thousands in the street protesting for shortage of food. The dependency of food from abroad is naturally tied to world food prices and shortages of food elsewhere. The increasing land use pattern favoring cotton over home grown food can play a dangerous catch 22 that cannot be altered. While this continues, climate change will only act as a conflict multiplier to put further strain on food security, which can lead to food riots and other violent conflicts in near term future.

2. Description

|

| Source: Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection |

The political struggle

The poor condition of Burkina Faso has been evident from the colonization by the French since the near end 19th century. Like many other colonizers, the French colony only concentrated on developing and building infrastructure on coastal regions with rich minerals and metals. Back then recognized as Upper Volta, the land locked Burkina Faso was not developed as much as its neighbors like Cote d'Ivoire. In 1960, the French gave up the territory and Upper Volta got its independence. Still struggling to perform economic growth, and stumbling upon ethnic conflicts and corruption, Upper Volta witnessed its first bloodless coup of President Yameogo in 1965. Dictatorship further increased political instability as he dissolved national assembly and prohibited political activity. Since then, there were three more coups, back to back overthrowing its previous leaders: Lamizana in 1980; Zerbo in 1982; Ouedraogo in 1983. Here's a video showing a brief overview of all the leaders from Burkina Faso since 1960:

In symbolic rejection of the nation's colonial past, Upper Volta became known as Burkina Faso in 1984. The name is a composite of local languages and is roughly translated as "The land of incorruptible men". In 1986, the military leader, Thomas Sankara, responsible for previous coup, came in power. Although Sankara was unpopular internationally for his anti-imperialist policies, he promoted nationalism and pushed the country forward toward economic development. Later assassinated in 1987, Thomas Sankara initiated a trend towards the country's self-independancy. Captain Blaise Compaore, after Sankara, continued to attract foreign investment and expanded the private sector. Here's a video on Thomas Sankara and his dream of a self-independent nation.

| "Our country produces enough to feed us all. We can even produce more than we need. Unfortunately for lack of organization we need to beg for food aid. This type of assistance is counterproductive and kept us thinking that we can only be beggers who need aid." ~Thomas Sankara, President of Upper Volta/Burkina Faso 1983-1987 |

The Economic Growth

During late 1990s, the country shifted its attention from political instability to macro-economic growth. Following a period of virtual stagnation in the early 1990s, Burkina's gross domestic product grew by an average 5.5 per cent over 1995-97. With Compaore government, the country started embarking on the road to economic liberalization. With the new constitution in and multiparty system in 1991, the country also reached a sound political democratization. The World Bank ranked Burkina as one of first African nation to have 'large improvement' on their macroeconomic policies between 1981-86 and 1987-91 (Harsch, 1998).

|

Source: The World Bank |

Several constructive developments were done to the country since 1984 to combat the effects of desertification and improve rural water access. Hundreds of mini-dams, reservoirs and wells were constructed, while millions of tree seedlings were planted to help slow soil erosion. The railway line running from Abidjan to Ouagadougou was extended 100 kilometers deeper into Burkina's northeast.

Further, the Compaore government took on massive initiatives to improve cotton production that faced significant decline in the early 1990s. From a low of 117,000 tons of seed cotton produced in the 1994 season, the harvest nearly tripled to 334,000 tons by 1999 (Maninski, 2007). This recovery was due to significant investment on infrasture like feeder roads and ginneries (Maninski, 2007). Also, a steady increase in the official producer price helped producers to earn revenues. Other reasons for such recovery was easy access to credits for fertiliser, insecticides and high-yielding seeds, all of which was provided by parastatal Sofitex, which is the monopsony of cotton in the country.

|

Burkina Faso, Large scale cotton production (Source: Getty Images) |

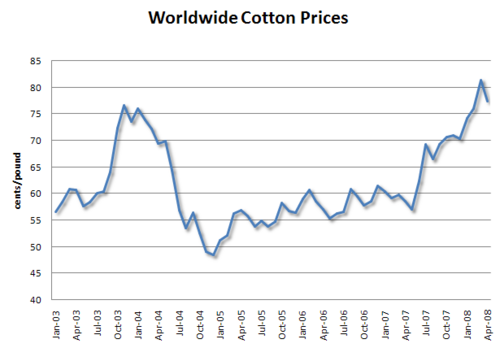

While increasing cotton harvesting is essential for boosting GDP in Burkina Faso, it is important to note that the world cotton price is a major determinant for inflow of export revenue for the country, which can either make a country benefit or suffer. As shown on the graph, the benefit was seen in 2002, when world cotton prices steadily rose and Burkina Faso earned higher GDP in return.

However, opposite was seen in 2004/2005, where world cotton prices fell. One of the biggest hits poor West African countries faced in cotton industry is when major cotton producers like USA and China subsidize their local cotton farmers. During 2004, USA government gave a total of $4.2 billion to local cotton farmers, which is more than the entire GDP of Burkina Faso. Such cotton subsidies cause over production, lowers prices and cause significant losses for a poor nation like Burkina Faso. (Oxfam International, 2005). The head of Oxfam International stated this cotton case in 2004 as an unfair trading system, where rich countries can afford to save its local farmers, while causing huge loss to poor countries' farmers due to low prices. This scenario only illustrates the vulnerability for Burkinabe cotton producers as they are highly dependent on world food prices.

| "The case of cotton demonstrates the unacceptable unfairness in the world trading system. US cotton subsidies cause overproduction and dumping, push down world prices and lead to drastic losses for Africa." ~said Celine Charveriat, Head of Oxfam International's Make Trade Fair campaign. |

The Trickle down effect in growth

While Burkinabe farmers are vulnerable to world cotton prices and ultimately end up suffering the most in the cotton industry, they also don't benefit much from country's high GDP growth. High GDP of Burkina Faso doesn't get tapped into subsidizing farmers either. The trickle down effect is almost nil when it comes to the poor farmers. Also, privatized SOFITEX often sets a fixed price before a harvesting season and buy all production from local farmers.

Contrary to the image of improved economic growth and political stability, the conditions faced by the poorest 10 million people continues to lead a very low standard of living and are unaffected by growth (Lay, 2009). The boasting of its economic growth by the President Compaore and other officials often created frustrations by the rural Burkinabe, both cotton and non-cotton farmers.

While improvements on infrastructure and methods to improve production efficiency greatly benefited cotton producers, who were backed with financial stakeholders, the poor non-cotton producers hardly benefited from the infrastructure. As cotton plays a major role in boosting economic growth, private enterprises spend more investment on cotton, which leaves all other food production to remain in low productivity rate. This results in rural inequalities to exacerbate, especially among the cotton farmers and non-cotton farmers in the rural regions. This either increase incentives to switch to cotton production or migrate to urban areas for better opportunity, which often worsens situations for households.

The Cotton industry

|

Source: Africamission-mafr |

Going back to the success story of the cotton industry, it has

been recent phenomena in the country. Due to absence of natural

resources like oil, diamonds, uranium like its neighboring countries,

Burkina Faso since 19th century used the land for subsistence farming,

livestock, growing peanuts and cotton. While the potential for Cotton

growing was recognized from 1960s, the production didn't take off due to

inadequate equipment, low productivity, lack of modified seeds and

proper investment.

Today, cotton exports accounts for approximately 52% of exports from Burkina Faso over the period 1995-2000, or approximately 105 million US dollars per annum (Maninski, 2007). It is the main exported commodity in terms of monetary value and keeps 3.5 million people in business in Burkina Faso. While West Africa is the 5th largest cotton producer in the world today, Burkina Faso is the largest producer within the region. It is technologically and financially advanced in the field of cotton. As of 2003, it was the first nation in West Africa that was authorized for field trial for transgenic cotton. This only asserts that the country truly have utilized maximum capacity to boost this industry. Cotton production is concentrated in West of Burkina Faso. The main cotton production areas within the country are Comoe, Kossi, Mouhoun, and Kenedougou. Most cotton-farms are family-owned and small-scaled and they all sell their production to one buyer called SOFITEX.

|

Source: UNCTAD |

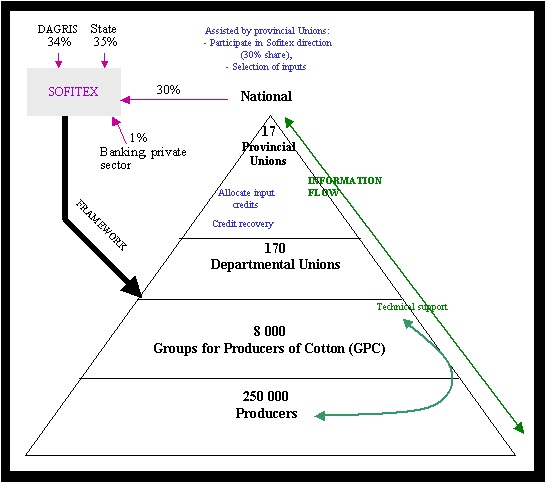

Burkina Faso's cotton sector is one of the strongest agro-industries in Africa. SOFITEX, the former State enterprise, is responsible for most of the commercial and industrial activities of the sector. SOFITEX is a monopsony, where it is the only buyer, buying from all cotton producers, either large producers or small family producers. In 1999, the national cotton producers' association ("Union nationale des producteurs de coton du Burkina Faso" - UNPCB) purchased a 30% share in SOFITEX. DAGRIS (Developpement des Agro-Industries du Sud), a French public holding company dedicated to cotton cultivation in the franc zone, holds 34% share; and the Government retains a share of 35%. Private sector banks only holds the residual 1% share. SOFITEX is responsible for all the steps of the value chain: purchasing of seed cotton, sale of inputs, ginning, processing, transportation, marketing, etc (UNCTAD, 2011).

The Figure on the left shows the breakdown of shareholders and organizational division within SOFITEX. Dividends are paid out and distributed among the members of the association. Actual exporting of different cotton products are then carried out. 66% of ginned cotton and the lint is exported to South-East Asia, 20% in Europe and the rest in rest of Africa and South America. As discussed above, there is a guaranteed fixed price to the cotton producers before harvesting season each year. Within the revenue return, 50% goes to growers, 25% to the State, and 25% to Sofitex (UNCTAD, 2011). While the share for growers is high, in reality, during a drought or low world prices for cotton, the farmers have to take the biggest hit.

Source: Dr. Molly's Presentation |

A Concern for Food Security?

As the success of cotton story is praised internationally, there is a long term effect of the story that often doesn't reach headlines - food security. Food security according to FAO's definition is when "all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life" (FAO, 1996). Food security is met in a country when all components of a food system (shown in the figure) are balanced. Food systems encompass food availability (production, distribution and exchange), food access (affordability, allocation and preference) and food utilization (nutritional and societal values and safety). In the case of Burkina Faso and the impact of cotton industry, we will concentrate mainly on food availability and food access.

Food insecurity in Burkina Faso can be caused by a range of factors and especially when they act in combination. Population boom is a crucial factor when it comes to food availability. A high population growth of 3.6 percent and total of 16.8 million people, Burkina Faso is said to double its population by 2050 (CIA, 2011; UN Population Division, 2003). As there is a shift in decline of local food production due to high demand for growing favored cash crop, availability of local food will continue to decline. Population boom will worsen this situation as there will be more mouths to feed. Shortage of food in an already food aid dependent country can lead to starvation along with frustration and tension among locals.

Food access becomes the next important factor, where rural-urban dynamics of a country becomes crucial to look at. Africa in general is predicted to have doubled its urban population by 2030 and Burkina Faso is no exception (UN News Centre, 2008). With high population growth, declining incentive for subsistence farming, and rise in urbanization, it can be predicted that rural-urban migration will only increase in the future. This will cause a rapid change in accessibility of food, where food can mainly be accessed via employment. Any determinants of accessibility, like high unemployment rate and high price of imported food will naturally lead to tension and conflict.

|

Food riot in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, February 2008. (Source: Irin, 2008) |

During February to April of 2008, as the world witnessed doubling of world food prices, Burkina Faso witnessed numerous violent food riots in the Cocody and Yopougon districts of Abidjan. Thousands of Burkinabe were in the street protesting for shortage of food and high price. Out of 1,500 protesters on average, one was killed and many were injured (IRIN, 2008). While this incident reflects mainly on high world food prices, the vulnerable agricultural state of Burkina Faso will likely to weaken the food system further and face future food riots.

The figure below shows the price of food and fuel reaching its record high in 2008. As highly populated Burkina Faso concentrates on cash crop production, its dependence on food import will naturally rise. The country has to prepare itself for its susceptibility towards world prices and shortage of production elsewhere.

Source: Dr. Molly's presentation |

Climate change will add a further dimension to the challenge of ensuring food security, affecting mostly the poor. Climate change will most likely affect food systems in several ways. It may directly impact on food production, hence on food availability (IPCC, 2007). Other impacts will be water shortage for irrigation for both cotton production and food, temperature suitability for agriculture and lastly desertification (IPCC, 2007). In this case, increase in cotton production in the land use pattern means less availability of land and irrigation channels to yield further crop production.

|

| Source: Eso Hank, 2008 |

3. Duration

Begin Year: 1990s

End Year:

Currently ongoing

Duration: 20 years and continue

During 1990s, ever since reforms of liberalizing commodity markets started in West Africa to privatize the parastatal SOFITEX, we can imply the start of a potential threat to food security. From an economic prospective, while it can be seen as an essential tool for poor country to boost its GDP by specializing in mono product, it meant more and more poor farmers switched from subsistence farming to cotton farming for a better monetary return. Producing cotton was a strategy-led policy to boost cotton production and increase export. Rapid land extension of cotton field in overall land cultivation of Burkina Faso followed right after. In February-April of 2008, during one of the highest world food prices in history, the country witness violent protests, about 1,500 protesters marched in Cocody and Yopougon districts of Abidjan. Although cotton industry is not the reason for food riots, it has potential to put strain on the food system of Burkina Faso, and hence food security is an ongoing issue and it is likely to get worsen in long term future due to climate change.

4. Location

The impact of food security can be visible in cities, where most of the food riots have taken place in the past. As discussed earlier, some cities include in the district Abidjan, namely Cocody and Yopougon. Food riots were also witnessed in the capital, Ouagadougou.

|

Bobo-Diolasso, Burkina Faso, April 28, 2011. (Source: Reuters Africa, 2011) |

As food riots are seen mainly in urban areas, there are also protests in cotton production sites, where farmers are demanding for a better cotton price. This is because the income level of cotton producers has a direct impact on the accessibility of food. One recent example was witnessed on April 28, 2011, where hundreds of cotton farmers in Bobo-Diolasso protested to raise cotton prices and increase subsidies to ensure revenue for 2011-2012 season. (Reuters Africa, 2011)

5. Actors

Parastatal SOFITEX, the monopsony of cotton industry

Burkina Faso Government

Burkinabe Cotton farmer

Major cotton producing countries: USA & China

One of main actors that play a major role in food security of Burkina Faso is SOFITEX, as they strengthen country's GDP by growing more cotton. The government of Burkina Faso also plays even a bigger role in encouraging more cotton production and not investing enough to cultivate land for local food production. The government is also responsible for providing subsidies for the cotton farmers. Its failure to do so will result in more protests on cotton price as rich nations start subsidizing their cotton farmers and drop cotton price. Burkinabe cotton farmers are the victimized actors, where they have no choice but produce just enough cash crop to make a living. The unemployed Burkinabe are the victims of high food price, who are often responsible for starting protests. Hence, they also play a role in food security of the country.

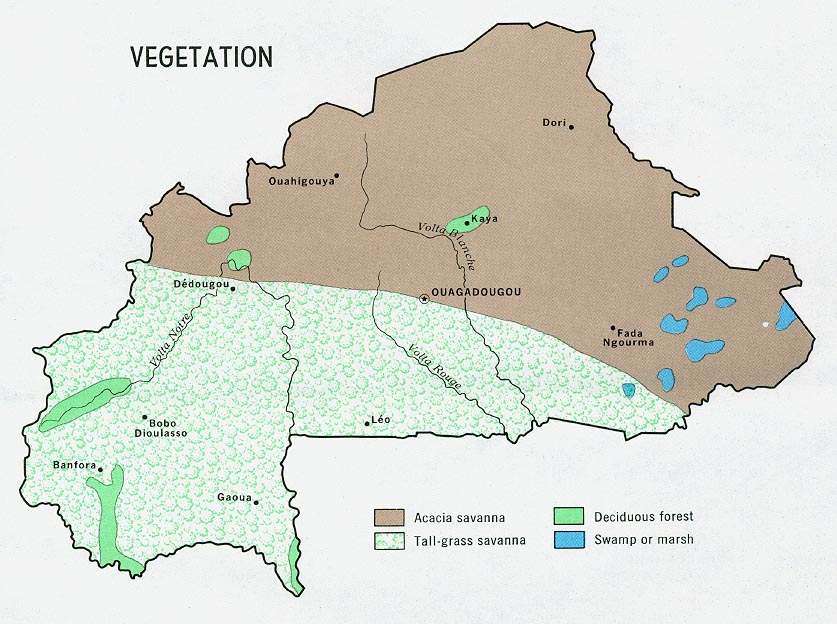

The growth of cotton production will ultimately change the land pattern of rural areas of Burkina Faso, which will in turn affect the environment. Since the 1960s, the country has gone through major transformation in economic activity, population growth and land use pattern. Below are the maps showing the environmental aspect of Burkina Faso.

1. Type of Environmetal Problem

Land use pattern in 1960s-1980s based on economic activity, population and vegetation

|

Burkina Faso is primary

divided into two regions in terms of climate and vegetation. The north

part of the region is dryer and likely to face semi-arid condition in

the future. As seen from the map on the left, the south part of the

country is mainly comprised of tall-grass savanna and decidious forest.

However, compared to 40 years ago, the country has on average received

less precipitation rate according to IPCC, which changed the vegetagtion

structure of the country. With increasing human activity in cash crop

production, there is a tendency for decline in natural vegetation of the

country. |

|

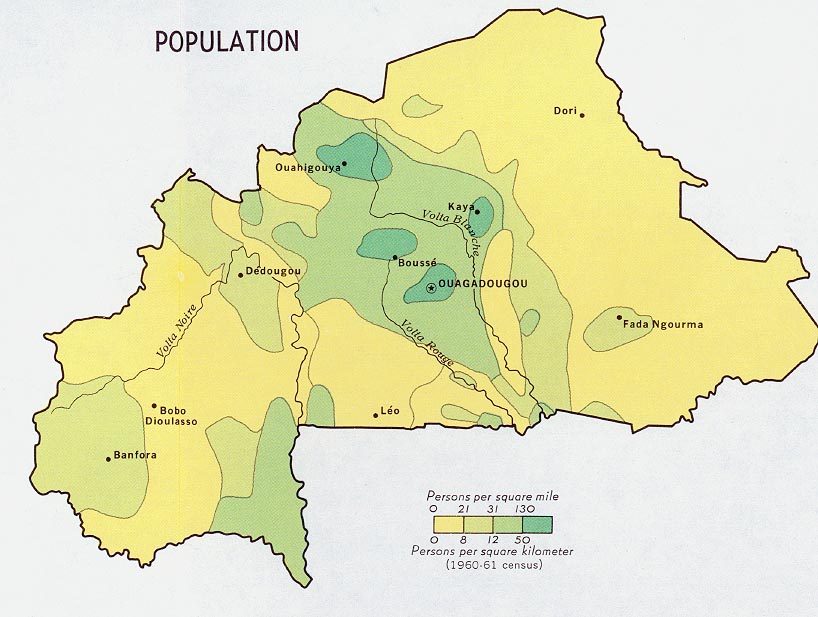

World census 2010 data for population

for Burkina Faso is 16.8 million. The map on the left shows the higher

density in the cities, mainly its capital, Ouagadougou. While this is

still the case today, with population growing more than 3.1% a year,

population density will rise even higher in cities and outskirts of

cities. This will create a negative impact on the environment, where

forests and trees need to be cut down to accommodate the high level of

population. |

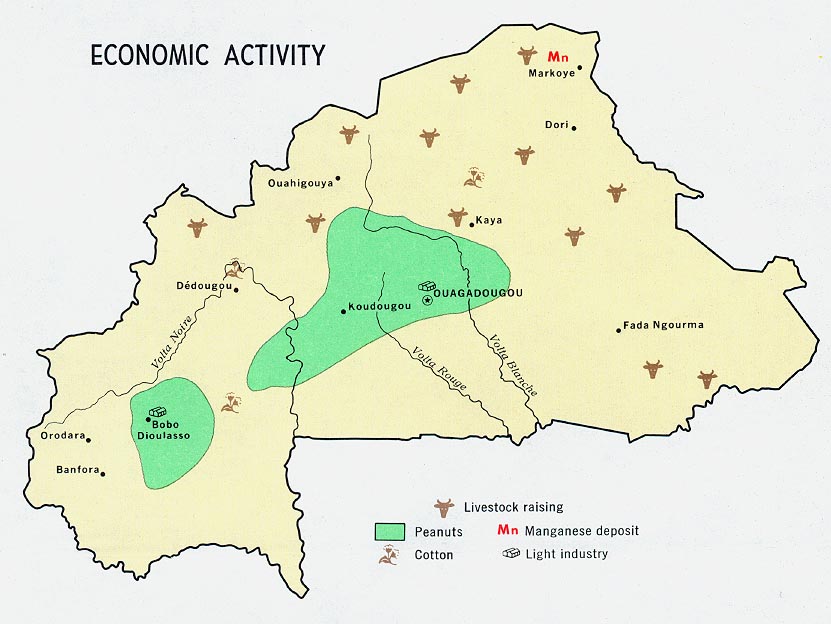

|

As seen on the map on the left, cotton

production was relatively on a small scale in the 1960s. (see map

below). As the country shifts towards cash crop production, where there

is high incentive and infrastructure, there will be a big shift in land

use pattern due to change in agricultural activity. This will also have a

huge impact on the environment. |

2. Type of Habitat

Burkina Faso is a landlocked country and is hardly affected by the tropical coastline like that of its neighbors - Cote d'Ivoire, Ghana and Benin. The country, in general, ranges from Savanna grassland in the north to deciduous forest in the South. Below is a detailed map of the four agro-ecological zones and its description on the table.

Source: Kagone, Hamade (FAO), 2006 |

Another aspect of habitat depends on the precipitation level. The level of precipitation in Burkina Faso is higher in the south than north as shown below. This is one of the reasons why the agricultural production is higher in the western and southern region of the country than the north.

Source: Atozmapsdata, 2010

For more interactive map, click here.

3. Act and Harm Site

The harm site is within the Country, Burkina Faso. Harm sites are mainly targeted towards the cities.

Strain on Arable land

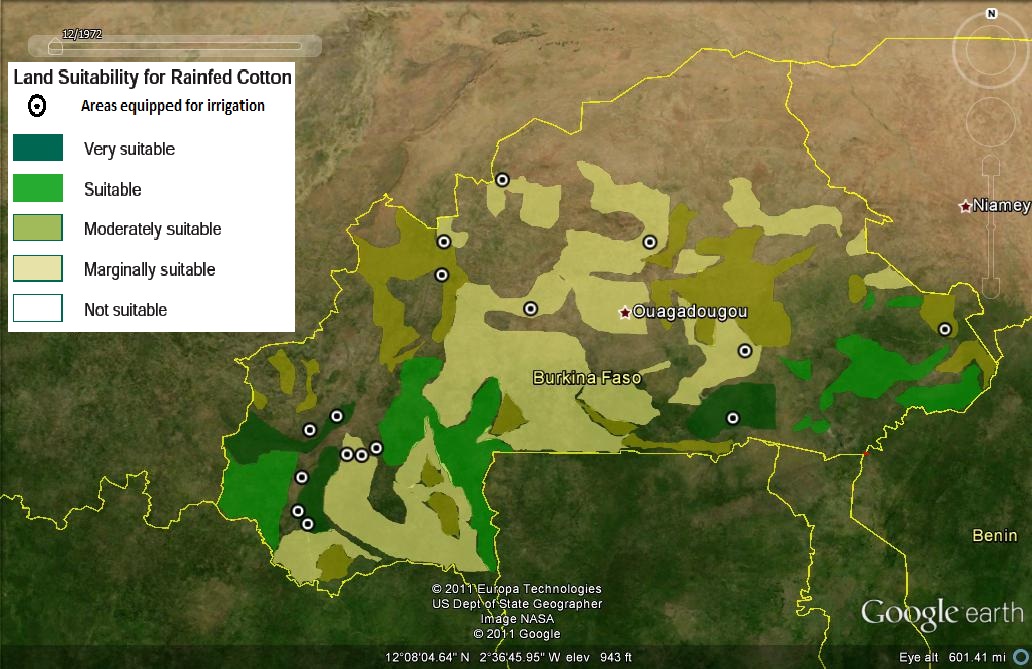

One of the objectives of this case study is to show that Burkina

Faso's arable land is on constant strain between agricultural exported

products (i.e. cotton) and food products for locals. The map

illustrates two key data, mainly land suitability for rainfed Cotton in

Burkina Faso and areas equipped for irrigation in the country. As you

can see from the map, areas that are equipped for irrigation are mostly

near 'very suitable' or 'suitable' land for growing cotton. There are

also other dry areas where irrigation can be practiced, but generally,

the areas where irrigation can't be practiced, cotton growing is not

suitable. Since irrigation is a core source of success in farming in

both cotton and local food products, an opportunity cost will have to be

made between the types of farming in these irrigation equipped areas.

FAO publication from 2000 shows that the

country's cultivated land compose of 13.3% national land (36,380

kilometer square), which is 40.4% of all arable land. While arable land

holds a small percentage of national land, agricultural land is

increasing at 3.6 percent annually from that of grazing lands, which

consists of 61% of national land including fallows, marginal land and

reserved land (FAO, Country Pasture). The growth of the artificial

agricultural land, at the expense of grazing land, may shift towards

more cotton farming due to government incentive than local food

products.

There is an incentive for the government to

increase its Gross Domestic Product, which comes from its major

exporting product, cotton, comprising of 52% of national export. If

the government pushes for more cotton production around the irrigation

equipped areas, then local farmers won't be able to grow food products

for local markets as much. As climate change decreases arable land in

the country, the country is forced to be more dependent on foreign food

either in terms of import or food aid. According to 2000 statistics,

Burkina Faso already receives almost 8% food aid among its total

consumption, which is 20% of its whole total imports (Earth Trends).

High dependency on foreign food will make countries to be vulnerable

during high world food prices. Local farmers will be forced to migrate

from arable land to urban areas. This has been the case for many West

African countries and will continue to create an inflow of population

from rural villages to cities, where food riots are common when world

food price skyrockets.

Cities are more prone to experience food riots because the people have to rely on food in the market unlike the local subsistence farming in rural villages. As it is most of the food product in the country is exported from abroad. Rice for example, which has increasingly become the staple food of the country is imported from South East Asia. And as government can't subsidize enough to reduce world food price due to global climate change, there may be a tendency for the rise of frustration among the poor population living in slums and elsewhere who can't afford high prices of food.

1. Type of Conflict

The type of conflict that can be involved in food security are food riots and also protests on low cotton prices. In the future, if food security is threatened enormously, it can lead to a potential civil conflict.

In 2008, as we have witnessed global food crisis which caused doubling of world food prices, it caused food riots in many parts of Africa, including Burkina Faso. Here's a news clip in 2008 that talks about the causes of food riots.

Here's a clip by FAO that talks about the shortages of food in Burkina Faso and how FAO is trying to help mitigate the issue with better seeds etc. Still, Burkinabe farmers still have to depend on rainfed agriculture due to poor irrigation system.

2. Level of Conflict

Level of conflict in food security at this point in time in Burkina Faso can be said to be low.

3. Fatality Level of Dispute (military and civilian fatalities)

Fatality level of dispute can be said to be low.

IV. ENVIRONMENTAL AND CONFLICT ASPECT

1. Environment-Conflict Link and Dynamics

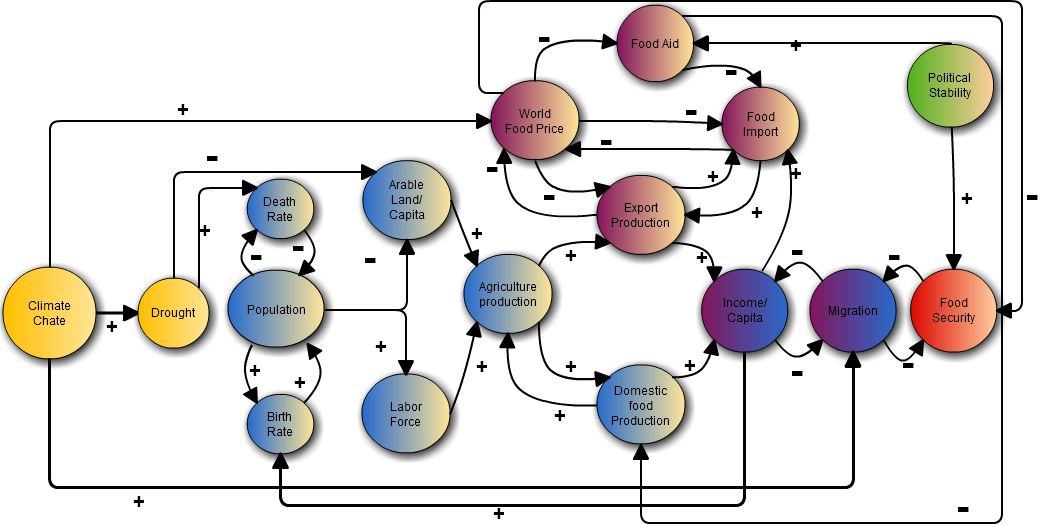

The environmental-conflict link of climate change and Burkina Faso's food security can be seen in the causal diagram as shown below.

Brief summary of the model

The causal diagram primarily focuses on the direct and indirect effects

of climate change on Burkina Faso's agriculture productions, namely

domestic food and export agriculture production, which can ultimately

lead to an effect on food security. The two dependent factors of the

productions are population and arable land. As we have seen earlier,

Burkina Faso has one of the highest population growths in Africa with a

3.6%. It has also a limited amount of arable land. Taking climate change

out of the picture, we would have a feedback relationship between

population, agriculture production and Income/capita. Unfortunately,

that is not the case. Over the 80s and late 90s, the country has

suffered from severe drought, which has caused massive starvation. As

climate change affects arable land, people and migration between

villages and cities, global climate change also affects the country via

rise in world food prices. Hence, this model tries to show how feeding

climate change into the agriculture production of the country can have

potential to give rise to food riots, indicated by food security.

Agriculture production cycle

The agriculture production is represented in the diagram with blue

shaded circles. Population affects the contributing factors of labor

force and arable land/capital to produce agriculture goods. As more

domestic food is produced, income/capita increases, which in turn

increases standard of living and higher birth rates, or rather infant

mortality rate. Higher population growth completes the feedback

relationship of the production cycle.

Burkina Faso produces most of its agriculture

food for its population. Its main export products include cotton, which

52% of their national export. With only 12% arable land available in the

whole country, an opportunity cost is involved to produce either

domestic food to feed its people or earn higher GDP by harvesting export

products (Earth Trends). Either way, both should lead to an

income/capita, represented by a positive sign.

World Food price & Foreign food aid

Burkina Faso's Export and Imports are dependent on world food

price and food aid it receives from France, EU, USA and USAID, UNICEF,

WFP etc. For years, global climate change has created food shortages

worldwide. With high dependency on food imports and globalization,

African countries get even more affected by the food shortages. Due to

West Africa's severe drought climate and its high dependency on food

imports, Burkina Faso is heavily affected by the rise of world food

prices. As world food prices rise due to El Nino or La Nino in another

region, the price of food imports rises, which leads to shortage of food

in the country. High world food price also means that it is more

expensive for donors to provide food aid, which makes the country even

more dependent on buying food imports. This cycle is not in equilibrium

and not self-sustainable as any fluctuation in one factor will cause all

other variables to collapse.

Linkage between domestic food production and world food price

There is a link between world food price and domestic food

production and that is food aid. As you can see from the diagram, the

more food aid the country will receive, the less demand there will be

for domestic food production. This will cause all the local farmers to

suffer, which will feed into the cycle to generate less income/capita.

Final Linkage to Food Security

High Food security is an indication of low frequency of food

riots. Over the last decades, almost all of food riots witnessed in

Burkina Faso was seen the urban areas, usually by the poor people, often

unemployed, who have moved to cities for better opportunity. Bad

harvesting seasons (due to climate change) and low income/capita are two

main reasons for the urban migration. As we discussed earlier, shortage

in domestic food production can ultimately create influx of migration

to urban areas. Poorer people living in the urban areas mean higher

unemployment, social disorder and poverty. World food price also have a

direct causal effect on the food security of the country. Accumulated

with high food prices, frustration and anger from poverty destroy food

security of cities, which in turn can lead to food riots.

2. Level of Strategic Interest

The level of strategic interest can be said to be low for now as there is no armed conflict involved yet. However, as food security is threatened in the future, the government will have to get involved and put the issue on its priority list.

3. Outcome of Dispute

The outcome of dispute is still to be determined as it is an ongoing issue.

1. Related ICE Cases

151. Tuaregs and Civil Conflict in West Africa by Ann Hershkowitz. ICE Case Study. August 2005.

Relation: This case study highlights the conflicts relating to desertification of West Africa.

225. UGANDA, Climate Change, GMO's and Conflict Process in Uganda, by Dillon Klepetar. ICE Case Study. December 2010.

Relation: Although this case study is on Genetically Modified food, it is very much related to shortage of food and inefficient food production due to climate change.

202. Madagascar Deforestion versus Agriculture Conflict, by Christopher Britton ICE Cases Study. May 2007.

Relation: This case study tackles the agricultural conflict with deforestation, which is putting strain on food product.

2. Relevant Websites and Literature

References:

Brown, Molly. "Droughts and Decision Making in Famine Early Warning Systems: The Role of Earth Science Data." Presentation at AU by Molly E Brown, PhD. 20 October, 2011

Lay, Jann. Narloch, Ulf. Mahmoud, Toman. "Shocks, Structural Change, and the Patterns of Income Diversification in Burkina Faso". African Development Bank 2009. (2009)

Maninski, Jonathan. Thomas, Alban. "Land Use, Production Growth,

and the Institutional Environment of Smallholders: Evidence from

Burkinabe Cotton Farmers". Land Economics (Feb 2007)

IFPRI. "World Food Situation." Population and Development

Review. Vol. 34, No. 2 (June 2008), pp. 373-380

<http://www.jstor.org/stable/25434697> 11 September, 2011.

Henry, Sabine. Schoumaker, Bruno. Beauchemin, Cris. "The

Impact of Rainfall on the First Out-Migration: A Multi-level

Event-History Analysis in Burkina Faso". Population and Environment,

Vol. 25, No. 5 (May 2004), pp.

423-460. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/27503895> September

11, 2011 .

"Domestic Transitions, Desiccation, Agricultural Intensification,

and Livelihood Diversification among Rural Households on the Central

Plateau, Burkina Faso". Colin Thor West. American

Anthropologist Vol. 111, No. 3 (September 2009)

Mertz, Ole. Lykke, Anne. Reenberg ,

Anette. "Importance and Seasonality of Vegetable Consumption and

Marketing in Burkina Faso." Economic Botany. Vol. 55, No. 2 (

2001), pp. 276-289. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/4256428 .Accessed:

09/11/2011> September 13, 2011.

Mazzucato, Valentina. Niemeijer, David. "Population Growth

and the Environment in Africa: Local Informal Institutions, the Missing

Link". Economic Geography, Vol. 78, No. 2 (Apr., 2002), pp. 171-193.

<http://www.jstor.org/stable/4140786> September 12, 2011.

Sakurai, Takeshi. Reardon, Thomas. "Potential Demand

for Drought Insurance in Burkina Faso and Its

Determinants". American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol.

79, No. 4 (Nov., 1997), Oxford University Press <

http://www.jstor.org/stable/1244277> September 13, 2011.

Reenberg , Anette. Lund, Christian. "Land Use and Land

Right Dynamics: Determinants for Resource Management Options in Eastern

Burkina Faso" Human Ecology, Vol. 26, No. 4 (Dec., 1998),

<http://www.jstor.org/stable/4603300> September 14, 2011.

Harsch , Ernest. "Burkina Faso in the Winds of Liberalisation"

Review of African Political Economy. Vol. 25, No. 78, Media in

Africa (Dec., 1998) pp. 625-641.

<http://www.jstor.org/stable/4006584> September 19, 2011

Taylor, Lynne. "Food riots revisited" Journal of Social History.

Vol. 30, No. 2, Winter 1996. University of

Waterloo. http://www.jstor.org/pss/3789390

Gray, Leslie. "What Kind of Intensification? Agricultural

Practice, Soil Fertility and Socioeconomic Differentiation in Rural

Burkina Faso". The Geographical Journal. Vol. 171, No. 1. Poverty and

the Environment (Mar., 2005) pp. 70-82. Blackwell Publishing. <

http://www.jstor.org/stable/3451388 .Accessed: 09/11/2011> September

14, 2011.

Fischer, GŁnther. Shah Mahendra. Tubiello, Francesco. Velhuizen, Harrij. "Socio-Economic and Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture: An Integrated Assessment, 1990-2080". Philosophical

Transactions: Biological Sciences, Vol. 360, No. 1463, Food Crops

in a Changing Climate (Nov. 29, 2005), pp. 2067-2083

<http://www.jstor.org/stable/30041395> 1 October, 2011.

Gregory, P. J. Ingram, S. I., "Climate Change and Food Security".

Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences. Vol. 360, No. 1463.

Food Crops in a Changing Climate (Nov., 2005), pp. 2139-2148

<http://www.jstor.org/stable/30041400> September 25, 2011.

Parry, Martin. Rosenzweig, Cynthia. Livermor, Mathew. "Climate Change, Global Food Supply and Risk of Hunger". Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences, Vol. 360, No. 1463. Food Crops in a Changing Climate (Nov. 29, 2005) pp. 2125-2138 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/30041399> 3 October, 2011.

Dyson, Tim. "On Development, Demography and Climate Change:

The End of the World as We Know It?" Population and Environment. Vol.

27, No. 2 (Nov., 2005) pp. 117-149

<http://www.jstor.org/stable/27503954> 11 November, 2011.

Schmidhuber, Josef. Tubiello, Francesco. Global

Food Security under Climate Change. Vol. 104, No. 50 (Dec. 11, 2007),

pp. 19703-19708 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/25450779> 7 October,

2011.

Sandor, Richard. Bettelheim, Eric. "An Overview of a Free-Market Approach to Climate Change and Conservation". Philosophical Transactions: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, Vol. 360, No. 1797, (Aug. 2002), pp. 1607-1620. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/3066580> October 13, 2011.

Worldpress. "The Plight of West African Cotton Farmers". Sustaining Change. (Apr. 2010) http://vanjalalic.wordpress.com/2010/04/04/the-plight-of-west-african-cotton-farmers/

The Plight of West African Cotton Farmers. Sustaining Change. A global perspective on a local world. http://vanjalalic.wordpress.com/2010/04/04/the-plight-of-west-african-cotton-farmers/ Oct 30, 2011

Oxam International. "Bumper subsidy crop for US cotton producers: African farmers suffer"

(Nov, 2005) <http://www.oxfam.org/fr/node/412> 23 November, 2011.

Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection. "Map of vegetation zones."

<http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/africa/africa_veg_86.jpg>

November 11, 2011

SOFITEX. 2005 <http://www.itfc-idb.org/content/sofitex-burkina-faso> November 12, 2011

UNCTAD-Info Comm. "Cotton Sectors in Africa." 2011 <http://www.unctad.org/infocomm/anglais/cotton/chain.htm> October 15, 2011.

CIA, The World Fact Food: Burkina Faso. 2011. <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/uv.html> November 1, 2011

United Nations Population Division. World Population Prospects:

The 2002 Revision. <http://www.unpopulation.org> December 1, 2011

UN News Centre. Urban African population set to rise sharply in next two decades €“ UN report. 2008. <http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=28924&Cr=population&Cr1=> December 1, 2011.

IRIN (Humanitarian News and Analysis). "BURKINA FASO: Food riots shut down main towns" 2008. http://www.irinnews.org/report.aspx?reportid=76905 October 3, 2011

Getty Images. Article in FT: Pick of the crop. < http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/80c5b0cc-4c56-11de-a6c5-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1gpriM0CE>

Eso, Hank. The impartial Observer. "Food Riots - The Coming Global Nightmare". http://www.kwenu.com/publications/hankeso/2008/food_riots.htm December 2, 2011.

Reuters Africa. "Burkina Faso cotton growers protest low prices."

April 28, 2011.

<http://af.reuters.com/article/topNews/idAFJOE73R06L20110428>

Mcclure, Matt. Cotton image. <http://www.burkinabymatt.com/index.php?subject=culture&photo=cotton_workers> December 2, 2011

Atommapsdata. Precipitation rate of Burkina Faso. 2010. <http://www.atozmapsdata.com/zoomify.asp?name=Country/Modern/Z_Burkin_Precip> November 11, 2011

OECD. Atlas on Regional Integration in West Africa. Land

suitability for rainfed cotton in Africa. Page 7.

<http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/42/25/38409410.pdf> August 23, 2011

Kagone, Hamade. " Country Pasture." FAO 2006. <http://www.fao.org/ag/AGP/AGPC/doc/Counprof/BurkinaFaso/burkinaFeng.htm> September 23, 2011

Earth Trends, Agriculture and food: Burkina Faso.

<http://earthtrends.wri.org/pdf_library/country_profiles/agr_cou_854.pdf>

Africa Mission- mafr. Image copyright. <http://www.africamission-mafr.org/situationsocioecogb.htm> September 3, 2011

IPCC. "Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report." 2007. <http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/syr/en/main.htm> December 2, 2011.