| ICE Case Studies

|

Climate Change & The Expansion of Canada's Continental Shelf: Impacts on Fisheries Management on the Grand Banks by Alicia Marrs |

I.

Case Background |

|

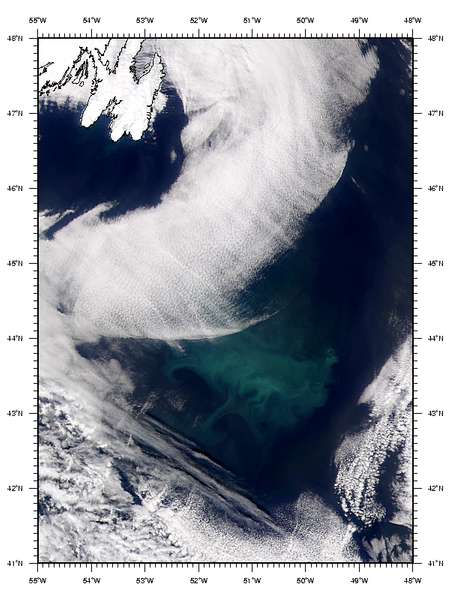

Mixing of Labrador Current and Gulf Stream |

The relatively shallow waters, coupled with the mixing of the cold Labrador current and the warm waters of the Gulf Stream have made the Grand Banks, located off of Canada’s eastern shore, one of the most productive fisheries in the world. Not surprisingly, the region’s resource rich waters have attracted intense fishing from countries from all over the globe for centuries. Unfortunately, this has culminated in seriously overexploited fisheries. As fisheries populations have become increasingly diminished, the conflict over the management of the fisheries in this region has escalated. Management of the fisheries of the Grand Banks falls under the jurisdiction of Canada (90% of the Grand Banks are located within its 200 mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ)) and the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO). Moratoriums on these fish stocks have been declared by both Canada and NAFO, but have not succeeded as fish populations continue to decline more than a decade later. As Canada and the other member countries of NAFO continue to struggle over the protection of the fish stocks of the Grand Banks, the conflict over fisheries management is only anticipated to escalate further as Canada submits a proposal to extend its continental shelf and the effects of global climate change begin to emerge.

The impressive biological productivity of the Grand Banks is attributed to the cold waters of the Labrador Current mixing with the warm Gulf Stream over a relatively shallow banks ranging in depth from 25 to 100 meters. These conditions result in an upwelling and a region of nutrient rich waters with high productivity which fuel the growth of marine organisms that range from microscopic plankton, groundfish like the Atlantic cod, seals, harbor porpoises and humpback whales. Over the past 400 years the region has supported one of the world’s most productive fisheries, but severe overfishing has resulted in the virtual decimation of many of its fish stocks. There are many factors that will contribute to whether or not the management of these fisheries erupts into further conflict, as global climate change and the extension of Canada’s continental shelf will throw new variables into an already overcomplicated equation. In order to best anticipate the potential conflicts that may ensue over the fishing rights of the Grand Banks there are 4 aspects that must be discussed: Canada’s jurisdictional authority of the Grand Banks in respect to its EEZ and continental shelf, the management of fisheries by Canada and NAFO, the threats of overexploitation faced by the fisheries and the potential effect global climate change may have on these fish stocks, especially Atlantic Cod.

|

| Fertile Grand Banks Plankton Bloom |

European explorers first discovered the abundant fisheries resources of the Grand Banks in the 15th century. It was not long before it attracted fishing vessels from all over the world, and served as the catalyst for establishing European colonies up and down the Atlantic seaboard. In fact, the first settlements in Newfoundland were created as bases for drying and salting fish for transport back to Europe. As 20th century technological advancements made for more efficient commercial fishing large vessels from Russia and Japan joined the European, Canadian and American boats that were already heavily fishing the region by the mid-1950’s.

Unfortunately, the pressure these highly efficient vessels were putting on the Grand Banks ecosystem became too much, and virtually decimated key stocks like the Atlantic Cod. The collapse in the Grand Banks cod population led to the Canadian government placing a moratorium on all cod fishing within its 200 mile EEZ in 1995. NAFO followed suit and declared a moratorium on the species as well. Unfortunately, both efforts have proven ineffective, and stocks continue to decline despite more than a decade of protection, and the future of management over the Grand Banks fisheries is not anticipated to get any easier. Excessive amounts of bycatch and illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing practices need to be halted. This is ultimately an effort that will demand cooperation between Canada and the member countries of NAFO.

A vast majority of the Banks (90%) falls within Canada’s 200-mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ), and Canada has long been searching for the way to bring the entire stretch of the extremely fertile submarine plateau of the Grand Banks within its jurisdiction. The remaining 10% of the Grand Banks that does not fall within Canada’s EEZ, is referred to as the “nose” and the “tail” the northern and southern most portions of the Grand Banks that is not within Canada’s EEZ. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) states have sovereign fishing rights within their EEZ. Thus, because the nose and tail do not fall within Canada’s EEZ management of these regions goes to the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO). Gaining sovereign control over the Banks is extremely important for Canada for a number of reasons, and is only further heightened by the impending onset of global climate change.

Finally, as the impacts of global climate change begin to emerge, there are predictions that some fish stocks like Atlantic cod in the northwestern Atlantic may actually rebound as a result of warming ocean temperatures. Assuming the stock was able to rebound, this development would turn the debate over the management of Atlantic cod on its head. The result would likely be a fishery which already has a history of being a highly coveted and contested would become the subject of even more international conflict. It will be a true test as to the strength and effectiveness of international resolutions like the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and regional fisheries management organizations like the Northwestern Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO) as to whether the conflicts over fisheries which may result from global climate change can be avoided, or at least mitigated.

Canada’s Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf

|

| (Courtesy of the

Department of Fisheries and Oceans - Canada) |

According to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), states can extend their continental shelf past the 200 nautical mile limit of their EEZ. This extended continental shelf (ECS) will give Canada the sovereign right to explore and exploit the living and non-living resources of the designated seabed and subsoil. While this includes rights to oil, gas and living organisms that are sedentary living on the seafloor, it does not, however, extend the state’s jurisdiction to include fish stocks. Sovereign fishing rights are limited to a state’s EEZ.

But just because sovereign fishing rights do not extend past a state’s EEZ does not mean that is the end of their ability to influence or protect these resources. Declaring an ECS also grants the coastal state exclusive control over marine scientific research as well as the sovereign right to control and prevent marine pollution in connection with any activities on the ECS. These activities also include the right to extract natural resources like oil and gas from the continental shelf. This could be both a positive and a negative development. While it allows the Canadian government to protect the nose and tail of the Grand Banks from activities like oil drilling by foreign companies and nations, it also means that Canada could decide to drill in these areas all on its own. Either way, this could mean many things for the fate of species like the Atlantic cod that may have a chance of rebounding due to the warming of ocean temperatures as an effect of global climate change.

In 1994, just before UNCLOS came into force, Canada began preparing a submission for an extension of its continental shelf. By expanding its continental shelf, it is estimated that Canada stands to gain approximately 1,750,000 square km (an area equal to the provinces of Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan combined), and would include the nose and tail of the Grand Banks. Under Article 76 of UNCLOS countries have 10 years from the date they sign on to UNCLOS to submit their petitions for an extension of their outer continental shelf. This means Canada is expected to submit its petition on or before November 7, 2013.

Management of the Grand Banks: Canada and the NAFO

|

NAFO Regions outside of Canada's EEZ |

In response to Canada’s unilateral declaration of its 200 nautical mile EEZ in 1977, the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO) was formed in 1978 to manage fisheries located outside Canada’s (and eventually any other country in the Northwest Atlantic) EEZ. The NAFO was established as a forum for international cooperation in science, conservation and management in the Northwest Atlantic. NAFO’s member countries include: Canada, Bulgaria, Cuba, Denmark (representing the Faroe Islands and Greenland), the European Union (representing Estonia, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Romania and Spain), France (on be half of Saint Pierre and Miquelon), Iceland, Japan, Republic of Korea, Norway, Russian Federation, Ukraine and the United States.

While NAFO does establish management policies for NAFO Regulated Areas (NRAs), its enforcement capabilities over fishing fleets within these waters are lacking. Instead fishing vessels are subject to the control of the country under which flag they are flying. If the country is a NAFO member state, they are obligated to abide by NAFO rules and regulations. Unfortunately, there are no established punishments for not abiding by these policies. The situation is worse for non-NAFO member states that have no obligation to abide by these policies.

In 2004 Canada committed to provide an additional $15 million in funding to further enhance its enforcement and surveillance program in the NAFO Regulatory Area with the goal of stopping illegal overfishing. These measures would include expanding Canada’s patrol presence from one dedicated vessel to three on the nose and tail of the Grand Banks (and on the Flemish Cap which also falls outside Canada’s EEZ, but within NAFO waters). A key element of Canada’s plan is to increase the number of boardings (under the auspice of NAFO observers) of foreign trawlers so they can monitor their level of compliance towards NAFO regulations.

Threats to the Fisheries of the Grand Banks

Long considered one of the most fertile regions of the world in terms of resources, Canada’s Grand Banks boasts some of the world’s richest oil deposits and fisheries. Nearly 90% of the Grand Banks fall within Canada’s EEZ, leaving only the “nose” and “tail” lying outside its jurisdiction. Over the years there have been many threats to the fish and shellfish populations endemic to this region ranging from over-fishing from domestic and international fishers, to the potential development of petroleum reserves thought to be located beneath the Banks.

Over-fishing /Illegal Fishing

One of the characteristics of the Grand Banks that makes it special is its unique position along the warm waters of the Gulf Stream (the Gulf Stream passes over the southern portion in the summer and covers almost all of the Banks in the winter.) These water temperature patterns, in combination with the relative shallowness of the water helps bring the nutrients to the surface, resulting in especially favorable conditions for growth of plankton. Plankton serves as the base of the food chain and is the direct food source for marine life of the Grand Banks ranging from Atlantic cod to humpback whales. The excessive supply of plankton on the Banks has made these waters especially fertile fisheries, as well as important spawning, nursery and feeding areas to large numbers of Atlantic fish and shellfish species, including the Atlantic cod.

Because many of these fisheries (including the Atlantic cod) have been so excessively over harvested, in 1995 they were closed on the Grand Banks in hopes of recovering their populations. Unfortunately, these fish are not stationary and do not stay within Canada’s EEZ (known as straddling stocks), making them vulnerable to fishers located outside of the EEZ’s boundaries. Throughout history there have been many disputes over fishing rights in these waters as Canada attempted to protect not only the health of the fish populations on the Grand Banks, but the local economies that depend upon them for their own survival as well. The problem was that not all Grand Banks fisheries were closed, and Canada suspected foreign vessels (especially from the European Union) of fishing in international waters with illegal fishing gear that would take moratoria stocks “inadvertently”.

Tensions reached their peak in 1995 when Canada boarded a Spanish fishing trawler that was fishing outside Canada’s EEZ in international waters. The Canadians, suspecting that the Spanish vessel the Estai was using illegal fishing gear, and in hopes of making an example of the trawler engaged in an all out pursuit that only ended when the Canadian’s fired a shot across the bow of the Estai and placed the crew under arrest. It was later determined that the Estai, which was supposed to be fishing for Turbot, another groundfish not under moratoria, was indeed using illegal fishing gear. While there was great controversy between the EU and Canada over the use of “extra-territorial force” (being that Canada had arrested the crew of the Estai outside of its EEZ) the case clearly demonstrated illegal fishing practices were occurring in NRAs.

Even though Canada and NAFO have imposed a moratorium on nine of the 20 NAFO managed stocks (including Atlantic cod) there has been little indication of species recovery. While this can be blamed on many culprits (the desperately low levels the population was allowed to reach before the moratoriums were put in place and illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing) one of the biggest worries for Canada and environmental organizations working on the preservation of the Grand Banks is the impact of moratoria stocks bycatch. It is estimated that up to 70-89% of the 3NO cod (southern Grand Banks cod) were harvested by vessels flying NAFO member flags in 2003. If fisheries management officials hope to recover moratoria stocks, it is becoming increasingly apparent that moratoria stock bycatch needs to be addressed and mitigated.

|

Canadian Aerial Enforcement of Grand Banks |

But regulating bycatch is a difficult task, and a certain level of bycatch is not only unavoidable, but allowed, under NAFO regulations. Unfortunately, there is evidence that fishing vessels are targeting and removing significant amounts of moratoria species (like Atlantic cod) under the auspice of permitted bycatch limits. The WWF estimates that bycatch of 3NO cod has increased to ten times the level it was at when the moratorium was established in 1995. In 2003 there were 5,400 tons of cod were taken as bycatch, this represents almost 90% of the estimated biomass of the stock and would offer an explanation for the perpetual decline in Atlantic cod populations despite the moratoria. The vessels which took the majority of the cod bycatch in this area were flying Portuguese, Spanish, Russian and Canadian flags.

NAFO has issued a number of measures to minimize bycatch like minimum mesh seizes, bycatch limits, sorting grates and small fish protocols, but it is difficult to determine whether or not fishing vessels are actually in compliance. Another problem is that there are vessels fishing in NAFO waters that are not NAFO members. Because the fishing is occurring in international waters, those vessels are not required to abide by NAFO’s management measures, thus further undermining the organization’s efforts. In fact, under international law all countries must consent to be regulated, which has been NAFO’s Achilles heel since its inception. While fishing by non-NAFO member vessels does not appear to be a major problem presently, it is expected to represent more challenges in the future. This would be especially true if the impacts of global climate change resulted in increased fish stocks in the Grand Banks while others in the Atlantic and else where in the world suffered.

Climate Change

Even though the excessive fishing of the Grand Banks has historically been its worst enemy, the desire to fish in the region could be exacerbated by global climate change. Increasing ocean temperatures and the potential shifting of the Gulf Stream have the potential to severely alter marine ecosystems, including the Grand Banks. As discussed previously, because of its unique placement along the warm waters of the Gulf Stream and its shallow depths, the Grand Banks have been an ideal home to many Atlantic marine organisms. But as waters warm and the Gulf Stream shifts, these highly adapted organisms may be forced to relocate, and potentially venture into international seas that are not protected as effectively as they are when they exist in Canadian waters. Some species like the Atlantic Cod are expected to experience a population increase, as well as an increase in their spatial distribution. While this may signify positive implications for the struggling cod population, it will undoubtedly result in an increased desire to reopen the fishery. Depending on the status of Canada’s application to extend its continental shelf and its jurisdictional management capabilities, tensions over management of this, and other northwest Atlantic species, will rise.

Canada declared its EEZ in 1977, thus creating the need for NAFO and international cooperation over the management of fisheries that fall outside of Canada’s EEZ. Management of the fisheries in and around the Grand Banks is currently under review by Canadian officials, the NAFO and environmental organizations. As the impacts of climate change emerge, this review will need to be constantly readdressed.

Grand Banks, Canada

Northwestern Atlantic Ocean, southeast of Newfoundland

Canada

Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO) and its member states: Bulgaria, Cuba, Denmark (representing the Faroe Islands and Greenland), the European Union (representing Estonia, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Romania and Spain), France (on be half of Saint Pierre and Miquelon), Iceland, Japan, Republic of Korea, Norway, Russian Federation, Ukraine and the United States (also includes Canada).

Countries that are not party to NAFO but fishing in the region are also considered actors in the conflict.

There has already been serious species loss in the Grand Banks due to overfishing, much of it illegal unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing by foreign flagged vessels. Canada and the NAFO have attempted to manage these fisheries at the international and national levels, but with limited success. These efforts will be further challenged by changes induced by global climate change, because as sea temperatures rise, the waters of the Grand Banks are expected to become even more fertile, potentially leading to the recovery of moratoria fish stocks like the Atlantic cod. If this were to happen it would likely perpetuate the conflict over fishing rights and privileges in the region.

There is relative uncertainty as to what the actual effects of global climate change will be on northwestern Atlantic ecosystems. Some species will benefit, while others will suffer making management of the region’s fisheries even more complicated than it already is. In fact, because climate change will most likely result in the warming of the waters off Canada’s eastern shores, and especially those around the already extremely fertile Grand Banks, many populations are expected to flourish, which will in turn lead to increased competition for access to these fisheries.

While there is virtually no doubt that the Atlantic cod has historically been overfished, and current efforts to manage its population are struggling at best, some scientists are predicting a potential surge in its numbers along the Grand Banks as a result of global climate change. As waters in the north Atlantic warm, Atlantic cod populations are expected to migrate to the shallow banks of the region, and flourish. Based on observations made on the cod’s response to temperature, some scientists predict that cod stocks in the Celtic and Irish Seas will most likely disappear by 2100, and those in the Georges Bank and the southern portions of the North Sea will also experience declines. And a recent report released by WWF-UK echoed these findings stating that increasing ocean temperatures coupled with fishing of an already seriously depleted fishery will most likely decimate the Atlantic cod stock in that region entirely.

|

Atlantic Cod |

But because of its migratory nature, cod populations are expected to migrate northward along the coasts of Greenland and Labrador, and are even thought to potentially occupy portions extending all the way to the continental shelf of the Artic Ocean, which is expected to open up by the melting Arctic ice sheet. In the end, the Atlantic cod population is expected to experience an overall increase in the North Atlantic, including the waters of the Grand Banks, due to the impacts of global climate change.

These projections are further strengthened by historical documentation of the effects of warming sea temperatures on Atlantic cod. During a cooling of the waters off the coast of Labrador and the Grand Banks in the late 1980s and early 1990s a southward shift in cod stocks was documented. While the opposite proved true in the Barents Sea during a warming period in the early 1990s. Warmer sea water temperatures don’t only effect the distribution and migratory tendencies of cod. Warmer seas are also thought to lead to faster growth rates, and earlier maturation. In the Grand Banks specifically, Atlantic cod have also been documented as spawning earlier when sea temperatures are higher. Ultimately, it appears that global climate change will result in a potential rebound of the Atlantic cod population in the waters of the Grand Banks, which could also signify an increase in the tension over fishing rights in the region’s seas.

There have also been recent discoveries of shifting ecosystems along the continental shelf of the northwestern Atlantic. While there will continue to be intense competition over cod fishing (especially if the stocks begin to recover either because of successful fisheries management, or as a product of global climate change), there will also be conflict over the right to fish for other groundfish and shellfish species in the region. As previously stated, many scientists now believe that one of the impacts of global climate change will be an increase in the productivity of these already fertile ecosystems. It is thought that because of increasing amounts of fresh water entering the northern oceans as a result of the melting of Arctic ice, surface seawater that would traditionally be very mixed will instead have a lower salinity and thus remain at shallower levels longer. Having sea water with a low salinity close to the surface longer will allow for increased production of phytoplankton, zooplankton and populations of fish that live near the surface. As these species remain closer to the surface longer, they also have more time to grow, and their production cycles will last longer. This has also led to larger populations of the fish that feed off of these species, such as herring.

The Grand Banks and the surrounding waters of the Northwest Atlantic.

If there is conflict it will be between Canada and other nations (primarily Western European countries) that want to fish in the waters of the Grand Banks. There may also be some sort of diplomatic conflict between Canada and international organizations/institutions (like the Secretariat of UNCLOS) if Canada decides to claim more territory than allowed under UNCLOS.

The potential conflict would be interstate (mostly likely between Canada and the European Union on behalf of Spain and Portugal) and the level of the potential conflict is low. Disputes over fishing rights and territories in the area (especially between the previously mentioned states) escalated to the heights of Canada arresting a Spanish fishing vessel in 1995 for using illegal nets. This confrontation occurred in international waters (high seas) during the Turbot War, which led to the protests of the EU. (See TURBOT case study for more information).

Despite the long history of disputes over the fisheries of the Grand Banks, there have been no documented casualties or deaths.

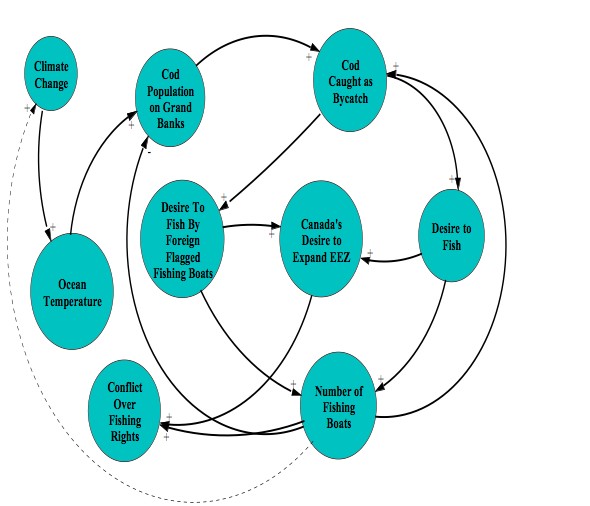

Climate change is expected to have a direct impact on the environment and the already present conflict over fisheries management in the Grand Banks. As ocean temperatures rise as an expected result of climate change, Atlantic cod stocks are expected to recover in and around the region as the population moves north. As cod stocks recover, the desire to resume fishing is expected to increase, both by Canadian and foreign flagged fishing fleets. This will have a direct impact on the number of fishing boats in the region, and have a direct impact on the level of conflict over fishing rights and management. Canada, which is already pursuing an extension of its continental shelf and ability to manage fisheries and other marine resources, will be further encouraged to establish this jurisdiction, which could intern also impact the potential conflicts over fishing rights, and Canada’s right to regulate foreign fishing vessels. However, if the moratorium is lifted because stock level had recovered, and fishing is resumed, the desire to fish the Grand Banks will undoubtedly increase as well. This will lead to an increase in the number of fishing boats and further necessitate the need for a strong and clear regulatory process for managing the fisheries so that they do not fall into the same cycle once more. The strength and effectiveness of this process will impact the number of fish, and the rate of recovery of the species, thus completing the loop.

(Though not addressed in depth, emissions from fishing vessels are also large

contributors to climate change. Thus, the more fishing boats there are operating

on the oceans, the more GHG emissions and thus increased levels of climate change,

which further perpetuates the cycle.)

Interest in the fisheries of the northwest Atlantic extends beyond the region’s coastal states as fishing vessels from all over the world utilize these waters.

The outcome of the dispute over fisheries management in the northwest Atlantic is still pending. As it stands currently, most parties agree that the NAFO is not as effective as it needs to be in order to adequately protect and manage species, nor resolve potential conflicts. If and when Canada does extend its continental shelf, the role of NAFO will need to be reevaluated. And if global climate change does in fact result in a recovery of Atlantic cod stocks on the Grand Banks, strong, clear and effective fisheries management will need to put in place.

The cases that surfaced with the greatest frequency were directly related to Canada and its fisheries, which historically have often been the source of conflict due to over-fishing and disputed territories. The cases of Turbot, Cancod , Canfish and Satellite-driftnets occurred the most often. The Turbot (No. 102) case study is essentially a precursor to the situation that has been analyzed in this case study (and was previously discussed in previous sections of this case study). Turbot analyzes the dispute over rights to fish in the NAFO waters especially by European vessels, and the conflict over coastal states' jurisdictional authority to enforce international/regional fishing regulations on the high seas. The primary difference between Turbot and this case study is inclusion of the unexpected impacts of climate change on the migratory patterns of the fish species in the region of the Grand Banks and the possible impacts of Canada extending it continental shelf. Another similar case is the Canfish (No. 62) case. This case study explores the limitations of coastal states trying to use UNCLOS to regulate environmental issues such as overfishing and pollution. One of the examples highlighted in the study was the previously mentioned conflict between Canada and Spain over the turbot fishing vessel. Unfortunately, two of the frist four case studies that are most related to the Canada-EEZ case study, Cancod and Satellite-driftnets do not have functioning websites at the present time. The Cancod case appears to have analyzed the management of Canadian cod stocks while the Satellite-driftnet case, which was the number 4 match, seems as though it is very similar in that it examines fishing disputes on the high seas.

The other related case studies do not relate quite as directly, but almost

all are disputes over management of resources or territory.

Related Cases:

| No. 102 - Turbot | Turbot Loss and Canada |

| No. 67 - Cancod | (Website unavailable) |

| No. 62 - Canfish | Canada and Spain Fishing Dispute |

| No. 107 - Satellite-driftnets | (Website unavailable) |

| No. 40 - Agean | Disputing the Continental Shelf Region in the Aegean Sea |

| No. 91 - Nicaragua -honduras | Nicaragua-Honduras Territorial Dispute |

| No. 54 - Haitidef | Deforestation in Haiti |

| No. 51 - Chiledam | The Bio-Bio River Case, Chile |

| No. 49 - Morspain | (Website unavailable) |

| No. 94 - Vineland | The Vikings in North America: Long-Term Climate Change, Environment, Trade, and Conflict |

Canadian Broadcast Corporation. “Northern Mapping Project Could Expand Canada.” July 21, 2005: <http://www.cbc.ca/health/story/2005/07/21/Ellesmere-map050721.html >

Cornell University. Warming Climate, Cod Collapse, Have Combined to Cause Rapid North Atlantic Ecosystem Changes. Science Daily. February 23, 2007 < http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/02/070222155140.htm >

Drinkwater, Kenneth F. The response of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) to future climate change. ICES Journal of Marine Scince. Vol. 62 (2005)

Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Canada’s Oceans Action Plan: For Present and Future Generations. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. 2005 < http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/canwaters-eauxcan/oap-pao/pdf/oap_e.pdf>

Fisheries and Oceans Canada - News Releases. Government of Canada Announces New Measures to Combat Foreign Overfishing. 6 May 2004 < http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/media/newsrel/2004/hq-ac45_3.htm>

Government of Canada. Backgrounder: The Grand Banks and the Flemish Cap.< http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/overfishing-surpeche/media/bk_grandbanks_e.htm>

Government of Canada. Backgrounder: The Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization.<http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/media/backgrou/1997/hq-ac38-1_e.htm>

Governmennt of Canada. Backgrounder: United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. <http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/overfishing-surpeche/media/bk_unclos_e.htm>

Government of Canada. Backgrounder: United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement.<http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/overfishing-surpeche/unfa_backgrounder_e.htm>

Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. The Grand Banks. < http://www.exec.gov.nl.ca/exec/premier/gbanks.htm>

Macnab, Ron. Canada and Article 76 of the Law of the Sea: Defining the Limits of Canadian Resource Jurisdiction Beyond 200 Nautical Miles in the Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. Geological Survey of Canada. Open File 3209. May 15, 1994

Nichols, S., D. Monahan and M.D. Sutherland. “Good Governance of Canada’s Offshore and Coastal Zone: Towards and Understanding of Maritime Boundary Issues.” Geomatica, Vol. 54, No. 4. pp. 415-424.

Planet Ark. “Depleted Canada Cod Stocks Face Devastation-WWF.” Ottawa, Canada: September 20, 2005: <http://www.planetark.com/dailynewsstory.cfm/newsid/32568/story.htm>

Rosenberg, Andrew, Marjorie Mooney-Seus, Chris Ninnes. Bycatch on the High Seas: A Review of the Effectiveness of the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization. WWF – Canada: September 2005 < http://www.wwf.ca/AboutWWF/WhatWeDo/ConservationPrograms/Marine/WWF-MRAGbycatchreport.pdf>

Rosenberg, Andrew A., Robert J. Trimble, Jennie M. Harrington, Oleg martens, and Marjorie Mooney-Seus. High Seas Reform: Actions to Reduce Bycatch and Implement Ecosystem-Based Management for the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization. WWF-Canada: July 2006 <http://www.wwf.ca/AboutWWF/WhatWeDo/ConservationPrograms/Marine/WWF-MRAGbycatchreport.pdf>

Stokke, Olav Schram. The Law of the Sea Convention and the Idea of a Binding Regime for the Arctic Marine Environment. The Fridtjof Nansen Institute

(Prepared for the 7th Conference of Parliamentarians of the Arctic region, Kiruna Sweden, 2-4 August 2006) < http://www.fni.no/doc&pdf/oss-2006-arctic-parlamentarians.pdf>

UNEP Shelf Programme < http://www.continentalshelf.org/>

U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy. An Ocean Blueprint for the 21st Century. Final Report. Washington, DC, 2004. ISBN#0-9759462-0-X

WWF-Canada. Bycatch Program - The Grand Banks. <http://www.wwf.ca/AboutWWF/WhatWeDo/ConservationPrograms/Marine/BycatchGrandBanks.asp>

WWF. Grand Banks - A Global Ecoregion. <http://www.panda.org/about_wwf/where_we_work/ecoregions/grand_banks.cfm>

WWF-UK. Cod is in Hot Water as Climate Change Compounds the Effects of Over-fishing. 6 May 2007 <http://www.wwf.org.uk/news/n_0000003884.asp >

Images:

"Canadian Aireal Enforcement of Grand Banks" Government of Canada - Overfishing and International Fishing and Ocean Governance<http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/overfishing-surpeche/en_inspections_e.htm>

"Atlantic Cod" <www.magazine.noaa.gov/stories/mag161.htm>

"Map of Grand Banks with Labrador Current and Gulf Stream" <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Banks>

"Map of NAFO Regions" < http://www.heritage.nf.ca/environment/banks.html >

"Map of Canada's Eastern EEZ & Continental Shelf"<http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/rma/dpr1/04-05/FO-PO/FO-POd45-PR_e.asp?printable=True>