| ICE Case Studies

|

|

I.

Case Background |

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts an increase in extreme weather events such as tropical cyclones in the Southeast Asian region. Cyclone Nargis, which struck Myanmar on May 2, 2008, illustrates the potential for extreme weather events to contribute to conflict. The event also provides insights into the role that stakeholders such as the United Nations and regional actors such as the Association for Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) can play in facilitating cooperation between disaster-impacted states and the international community.

Cyclone Nargis: The Immediate Aftermath

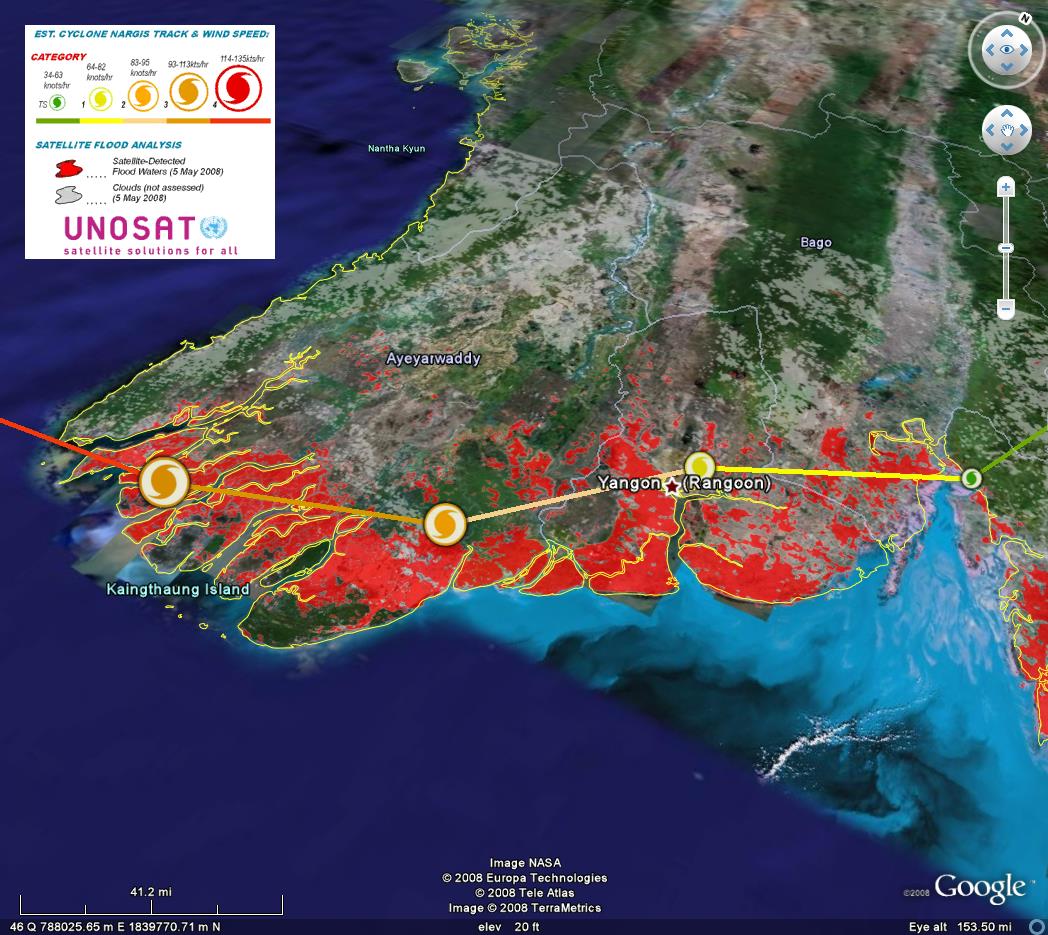

On May 2, 2008, Cyclone Nargis struck Myanmar with windspeeds of approximately 132 miles per hour and a tidal surge of 12 feet. After initially making landfall in  the heavily populated and low-lying Ayeyarwady Delta, the storm continued its destructive path east-northeast across the Bogo, Mon, Kayin and Yangon Divisions (USAID, USAID Responds to Cyclone Nargis).

the heavily populated and low-lying Ayeyarwady Delta, the storm continued its destructive path east-northeast across the Bogo, Mon, Kayin and Yangon Divisions (USAID, USAID Responds to Cyclone Nargis).

In its wake, Cyclone Nargis left immense destruction in coastal Myanmar. Nearly 140,000 people perished and hundreds of communities washed away as a result of the storm. By destroying crops and other critical infrastructure such as shrimp farms, fishing ponds, nursery hatcheries and fishing boats, Cyclone Nargis also robbed an additional one million Burmese of their livelihoods and left an estimated 2.4 million people without adequate food (WFP, Cyclone Nargis: Two Months Later).

Photo Courtesy of Digital Earth Blog

Although Myanmar produced an annual food surplus and was, at one time, one of the largest rice exporters in Asia, when Cyclone Nargis struck, the country was struggling to maintain basic food and health conditions for its population of approximately 50 million people. The 2007/08 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human Development Index, which measures basic dimensions of health, education and income, ranked Myanmar 132nd of 177 countries. Prior to the storm,  access to health facilities, inadequate water and sanitation facilities, poor maternal and child care and limited livelihood opportunities" (WFP, Myanmar Emergency Operation (EMOP) 10749.0 Food Assistance to Cyclone Affected Populations in Myanmar). In an unfortunate blow to the country's already tenuous state of food security, Cyclone Nargis was at its most impactful in Ayeyarwady Division, a region considered to be "the food basket of Myanmar" (FAO), which produced "65 per cent of Myanmar's rice, 80 per cent of its aquaculture, 50 per cent of its poultry and 40 per cent of its pig production"(Selth). In the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis, with critical infrastructure damaged and physical access to markets further in-land disrupted, Myanmar was, by many accounts, in need of both immediate and long-term humanitarian assistance (WFP, Myanmar Emergency Operation (EMOP) 10749.0 Food Assistance to Cyclone Affected Populations in Myanmar).

access to health facilities, inadequate water and sanitation facilities, poor maternal and child care and limited livelihood opportunities" (WFP, Myanmar Emergency Operation (EMOP) 10749.0 Food Assistance to Cyclone Affected Populations in Myanmar). In an unfortunate blow to the country's already tenuous state of food security, Cyclone Nargis was at its most impactful in Ayeyarwady Division, a region considered to be "the food basket of Myanmar" (FAO), which produced "65 per cent of Myanmar's rice, 80 per cent of its aquaculture, 50 per cent of its poultry and 40 per cent of its pig production"(Selth). In the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis, with critical infrastructure damaged and physical access to markets further in-land disrupted, Myanmar was, by many accounts, in need of both immediate and long-term humanitarian assistance (WFP, Myanmar Emergency Operation (EMOP) 10749.0 Food Assistance to Cyclone Affected Populations in Myanmar).

International Humanitarian Aid and the Responsibility to Protect (R2P)

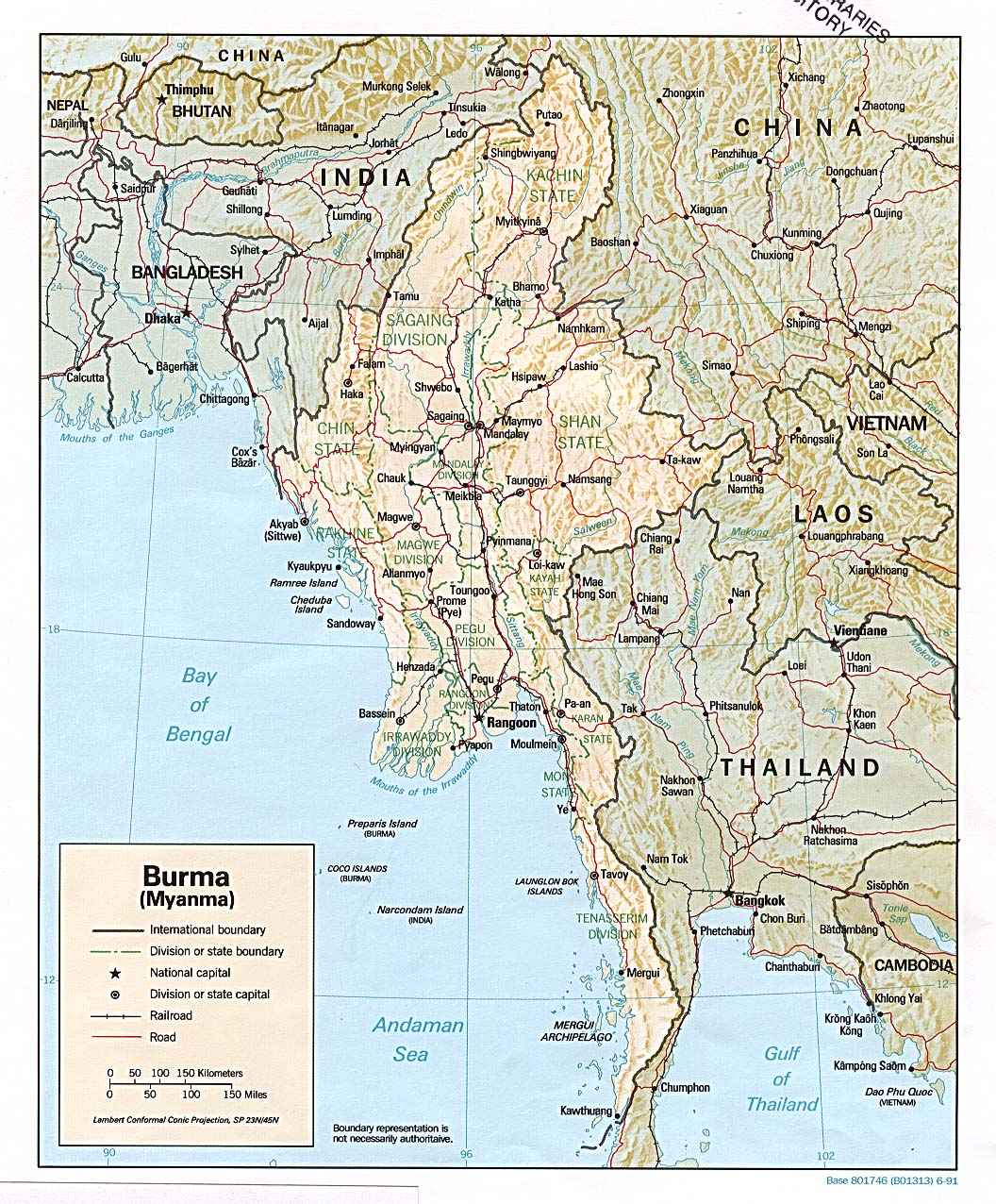

Map Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin

Within one week of the disaster, 24 countries had pledged a total of $30 million in aid to assist with humanitarian operations in Myanmar. On May 6, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), Myanmar's military government that took power in 1988, had declared that it would accept assistance, but only on the basis that it could maintain control of the flow of aid throughout the country. On May 7, five days after disaster struck, SPDC leader Senior General Than Shwe declared that the "situation is returning to normal"(Selth). Today, the Myanmar government maintains that, immediately after Cyclone Nargis struck, the military, "made a valuable contribution by calming fears, providing security, and maintaining peace and harmony in the affected areas"(ASEAN Tatmadaw). Nonetheless, General Shwe's remarks stood in direct contrast to reports from first responders such as Andrew Kirkwood of Save the Children, one of several non-governmental organizations (NGOs) working in Myanmar prior to Cyclone Nargis, who noted, "we know that some areas are still completely under salt water�some people have no drinking water or food. Unless assistance gets to those areas very soon, the death toll will keep rising" (Children).

Speculation abounds as to why the State Peace and Development Council chose to restrict aid in the days and weeks following Cyclone Nargis' landfall on May 2, 2008. Ongoing political operations may have contributed to the government response. Government official in Myanmar's capital of Naypyidaw were occupied with a constitutional referendum, originally scheduled for May 10, but rescheduled by two weeks in the wake of the cyclone, and continued to carry out polling operations in those parts of the country unaffected by Cyclone Nargis (Selth). Further, the government continued its on-going efforts to control pro-democracy groups including the National League for Democracy (NLD), led by captive opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi, and periodic conflict in regions such as Karen State in Eastern Myanmar (Ploughshares).

Along with intrastate politics, SPDC's hesitancy to accept international aid may have also related to the military regime's concerns about its public image (both inside and outside of Myanmar), as well its distrust of NGOs and international governments and their potential to sow seeds of unrest in the country. For the SPDC, accepting foreign aid without restrictions, "would have been tantamount to saying that they have broken a covenant with the citizenry by not being the main provider in times of need"(Ozerdem); further, allowing aid workers and international governments unrestricted access to the country, may have the potential to expose Burmese citizens to "alien influences" or foster "social instability"(Selth). Indeed, political scientists have theorized that, in an international political environment in which the United State Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice had recently declared Myanmar to be "an outpost of tyranny"Steinberg), and in which President George Bush had both renewed sanctions against Myanmar and labeled the proposed constitutional referendum as "dangerously flawed" (Selth), perhaps the military regime had reason to be wary of foreign intervention in the guise of international aid (Selth)(Ozerdem).

No matter what its reasons for restricting foreign aid, Myanmar's military regime and its response to Cyclone Nargis quickly attracted the ire of several heads of state and high-level politician including the French Minister for Foreign and European Affairs, Bernard Kouchner, who announced his intention to obtain a United Nations Security Council Responsibility to Protect (R2P) resolution on May 7, 2008. Kouchner was quickly followed by Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, who claimed that attempts to "bash the doors down in Burma" would be justified given the extent of the humanitarian crisis in the country. In response to a May 9, 2008 United Nations Flash Appeal for emergency aid, the United States, France, and the United Kingdom positioned naval craft with food and other forms of relief off of the coast of Myanmar(Selth) and the United States also positioned planes loaded with 129 metric tons of commodities, including plastic sheeting and hygiene kits, in Thailand, pending SPDC approval of aid(USAID, USAID Burma-Cyclone Fact Sheet #6 Fiscal Year (FY) 2008).

Though French minister Kouchner's call to forcibly introduce aid to Myanmar under the auspices of a United Nations Responsibility to Protect (R2P) resolution ultimately went unanswered, it did spark an international dialogue about the use of R2P to address natural disasters such as Cyclone Nargis. In the aftermath of notable humanitarian failures such as the Rwandan genocide in 1994, the R2P mechanism was developed by the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) and endorsed unanimously by 150 governments during the 2005 United Nations World Summit. R2P obligates the international community to "take coercive action for the protection of lives in the circumstances of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity" (Ozerdem) and operates under the following principles:

Though the rhetoric about R2P continued to gain traction in international circles in the weeks following Cyclone Nargis, the United Nations and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN (of which, Myanmar is a member country), gradually engaged the SPDC through diplomatic measures in an effort to facilitate humanitarian aid in Myanmar and quell fomenting international conflict.

The Tripartite Core Group and Post-Nargis Recovery

On May 9th, 2008, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Emergency Response Assessment Team became the first official team that the government of Myanmar allowed into the country post-Nargis (ASEAN, Post-Nargis Knowledge Management Portal ASEAN's Response ). Though UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon initially expressed disappointment in the military regime's handling of the disaster, expressing his "deep concern and immense frustration at the unacceptably slow response to this grave humanitarian crisis" Selth), by May 18, 2008 a UN envoy had arrived in Myanmar to begin diplomatic discussions with the SPDC.

Together, the Myanmar military regime, ASEAN, and the UN formed what would come to be known as the Tripartite Core Group (TCG) that would "facilitate the effective distribution and utilization of assistance from the international community, including the expeditious and effective deployment of relief workers, especially health and medical personnel"(ASEAN, ASEAN Post-Nargis Knowledge Portal ASEAN-Led Mechanism). The formation of the TCG eased tensions between Myanmar and the international community and, on May 23, 2008, Senior General Than Shwe invited foreign works, "regardless of nationality" (ASEAN, ASEAN Post-Nargis Knowledge Portal ASEAN-Led Mechanism), into Myanmar's borders. In early June, days after the TCG deployment in Myanmar and nearly a month after disaster struck, United States, French, and United Kingdom naval vessels departed from international waters off the coast of Myanmar, albeit with their humanitarian supplies still on board (Selth).

Post-Nargis Recovery

Today, some aid organizations claim that, despite some initial problems with aid distribution, Cyclone Nargis created an unprecedented opportunity work in Myanmar(WFP, World Food Programme Myanmar: Carving out humanitarian space post-Nargis). Signs of progress in post-Nargis Myanmar include the implementation of the 2009-2011 Tripartite Core Group Post-Nargis Recovery and Preparedness Plan and evidence that, despite extensive damage to valuable agricultural infrastructure in the Ayeyarwady and Yangon divisions, overall food production remained "satisfactory in 2008 because of increase in crop harvests in other regions eflecting favorable weather conditions and increasing use of better rice seeds"(WFP, World Food Programme Food Production Satisfactory in Post-Nargis Myanmar, But Access to Food Difficult for Many).

Despite signs of progress, Myanmar's military regime is still the subject of international scrutiny, most recently for its handling of national elections on November 7, 2010. After the first such elections since 1990, the government-supported Union Solidarity and Development Party won a majority of seats in the national parliament, state and regional assemblies with 92.48 percent of the vote (State, US Department of State 2010 Human Rights Report: Burma). Following the elections, pro-democracy activists and the international community criticized the process as being seriously flawed and as failing to meet "any of the internationally accepted standards associated with legitimate elections"(State, US Department of State Burma (Myanmar) Country Specific Information). Further, despite some goodwill as a result of the military regime's ultimate handling of Nargis aid, "armed violence, human-rights abuses and oppression continued [and] the military government continued to repress its ivilians through lack of basic human rights and attacks on rebel-held territories" (Ploughshares).

Was Cyclone Nargis Just the Beginning? Climate Change and the Potential for Future Conflict

In the midst of the heated discussion about the international community's Responsibility to Protect in the days after Cylone Nargis struck, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown observed that, "a national disaster is being made into a manmade catastrophe by the neglect and inhuman treatment of the Burmese people by a regime that is failing to act"(Selth). Brown's interpretation of the event differs greatly from the Myanmar government and ASEAN accounts; nevertheless, his sentiment reflects both international disposition in the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis and captures the potential for future conflict as global climate change continues to alter the lives of people in Myanmar via extreme weather events such as Nargis. How will future extreme weather events test the Myanmar government's relationship to the international community and its ability to govern? Further, given current International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projections, is it important to consider the impact that climate change might have on the potential for interstate and intrastate conflict in Myanmar?

Although uncertainty exists regarding climate sensitivity and emissions trajectories, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) nonetheless predicts that, over the coming decades, the Southeast Asian region is likely to very likely to experience an increase in temperature, precipitation, and extreme weather events including droughts, heatwaves, and tropical cyclones (Change). Indeed, changes in temperature extremes such as heat waves and an increase in the number of wam days and warm nights, as well as the number of heavy precipitation events have been observed in the last century. Further, the incidence of tropical cyclones has increased during both the summer (July to August) and Autumn (September to November) in El Nino/Southern Oscillation years (Bank). The 2007 IPCC Assessment predicts that a sea surface temperature increase of 2 to 4 degrees Celcius will result in 10 to 20 percent more tropical cyclones in the Southeast Asian region.

Given the level of conflict that resulted from Cyclone Nargis and given IPCC projections regarding the impact of climate change on extreme weather in Southeast Asia, it seems likely that, in the future, Myanmar and the international community will face challenges similar to those presented by Cyclone Nargis. While the social and political repercussions of future extreme weather events on Myanmar remain to be seen, experience with Cyclone Nargis may provide useful insights into potential sources of conflict.

Begin Year: May 2, 2008

End Year: June, 2008

Duration: One month

After initially making landfall in the heavily populated and low-lying Ayeyarwady Delta, the storm continued its path east-northeast across the Bogo, Mon, Kayin and Yangon Divisions (USAID, USAID Responds to Cyclone Nargis).

Continent: Asia

Region: Southeast Asia

Country: Myanmar

Sovereign Actors

Non-Sovereign Actors

Climate Change

Although uncertainty exists regarding climate sensitivity and emissions trajectories, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) nonetheless predicts that,

over the coming decades, the Southeast Asian region is likely to very likely to experience an increase in temperature, precipitation, and extreme weather events  including droughts, heatwaves, and tropical cyclones (Change). Indeed, changes in temperature extremes such as heat waves and an increase in the number of warm days and warm nights, as well as the number of heavy precipitation events have been observed in the last century. Further, the incidence of tropical cyclones has increased during both the summer (July to August) and Autumn (September to November) in El Nino/Southern Oscillation years (Bank). The 2007 IPCC Assessment predicts that a sea surface temperature increase of 2 to 4 degrees Celcius will result in 10 to 20 percent more tropical cyclones in the Southeast Asian region.

including droughts, heatwaves, and tropical cyclones (Change). Indeed, changes in temperature extremes such as heat waves and an increase in the number of warm days and warm nights, as well as the number of heavy precipitation events have been observed in the last century. Further, the incidence of tropical cyclones has increased during both the summer (July to August) and Autumn (September to November) in El Nino/Southern Oscillation years (Bank). The 2007 IPCC Assessment predicts that a sea surface temperature increase of 2 to 4 degrees Celcius will result in 10 to 20 percent more tropical cyclones in the Southeast Asian region.

Deforestation

The deforestation of mangrove forests in the southern coast of Myanmar may have increased the destructive impact of Cyclone Nargis on regional infrastructure such as homes, rice paddies, and fishing boats(Anonymous). Approximately 80 percent of the mangrove forests in the Ayeyarwady delta have been cleared since the 1920s to make way for rice farms and to contribute to fuel supplies. After Cyclone Nargis, an ASEAN representative identified, "encroachment into mangrove forests, which used to serve as a buffer between the rising tide, between big waves and residential areas" (Lean), as a contributing factor in the high death toll and infrastructure losses resulting from Nargis.

Photo Courtesy of Care2.com

Tropical

Myanmar, specifically the southern coastal region and the Ayeyarwady, Bogo, Mon, Kayin and Yangon Divisions.

International

Natural Environmental Changes

Political

Infrastructure

No direct deaths resulted from the conflict surrounding Cyclone Nargis. Approximately 140,000 Burmese civilians died as a result of the immediate impact of the storm and food shortages and health problems that resulted from the storm.

Indirect Fatality Level - High

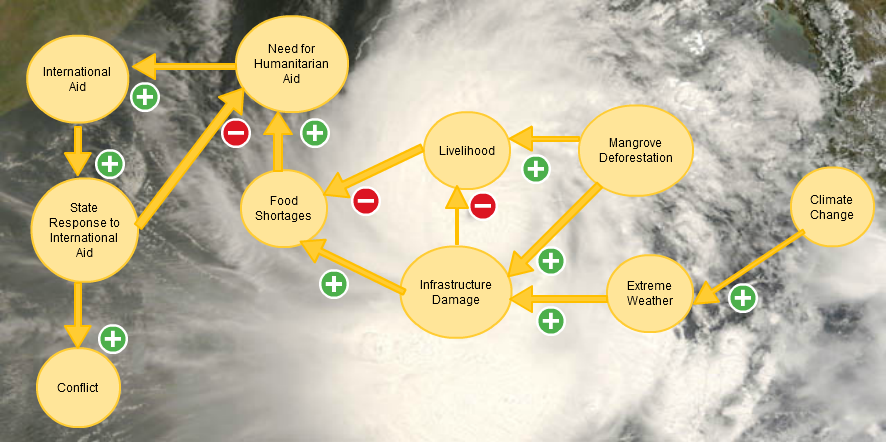

This causal loop diagram illustrates the relationship between climate change, international and national governance, and conflict in Myanmar in the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis in 2008.

Climate change contributes to an increase in extreme weather events such as cyclones (see Environment Aspects), which in turn increase the likelihood of infrastructure damage and food shortages and decrease the potential for livelihood in Myanmar. The relationship between climate, infrastructure, livelihood and food shortages is also closely related to coastal mangrove deforestation. While there is a positive relationship between deforestation and livelihood, with the addition of extreme weather events resulting from climate change into the system, deforestation increases infrastructure damage, thus increasing food shortages as well.

Following Cyclone Nargis, food shortages in Myanmar triggered an increase in international offers of an insistence upon humanitarian aid which, in turn, caused the Myanmar government to initially resist international aid. Together, the international community’s insistence on aid and the Myanmar government's rejection of such aid led to an increase in interstate tension and the potential for conflict in the region.

Climate change contributes to an increase in extreme weather events such as cyclones (see Environment Aspects), which in turn increase the likelihood of infrastructure damage and food shortages and decrease the potential for livelihood in Myanmar. The relationship between climate, infrastructure, livelihood and food shortages is also closely related to coastal mangrove deforestation. While there is a positive relationship between deforestation and livelihood, with the addition of extreme weather events resulting from climate change into the system, deforestation increases infrastructure damage, thus increasing food shortages as well.

Following Cyclone Nargis, food shortages in Myanmar triggered an increase in international offers of an insistence upon humanitarian aid which, in turn, caused the Myanmar government to initially resist international aid. Together, the international community’s insistence on aid and the Myanmar government's rejection of such aid led to an increase in interstate tension and the potential for conflict in the region.

State

Region

Multilateral

The Myanmar military regime, as well as states such as the United States of America, France, and Britain maintained strategic interest in the state of Myanmar following Cyclone Nargis. The multilateral governing body, the United Nations and the regional Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) collaborated with the state of Myanmar to devise and implement a plan for the distribution of humanitarian aid.

Compromise

The Myanmar military regime agreed to collaborate with the United Nations and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. As a result of this agreement, the international community agreed not to pursue the potential to invoke the Responsibility to Protect through the United Nations Security Council (see Description).

58. KORFAMIN North Korea Famine by Jennifer S. Wolfe (January, 1998)

209. HAITI-HURRICANE Climate Change, Extreme Events, and Haiti by Sterling Johnson

229. BANGLADESH Climate Change Induced Extreme Weather Events & Sea Level Rise in Bangladesh Leading to Migration and Conflict by William Alex Litchfield

Anonymous. "Mangrove Destruction Exacerbated Effects of Burmese Cyclone." Geographical Vol:80 Issue 7 (2008): 10.

ASEAN. ASEAN Post-Nargis Knowledge Portal ASEAN-Led Mechanism. 2011. 26 June 2011 <http://www.aseanpostnargiskm.orgresponse-to-nargis/tripartite-core-group/what-is-tcg>.

. Post-Nargis Knowledge Management Portal ASEAN's Response . 2011. 26 June 2011 <www.aseanpostnargiskm.org/response-to-nargis/aseans-response>.

Bank, Asian Development. The Economics of Climate Change in Southeast Asia: A Regional Review. April 2009. 24 June 2011 <http://www.adb.org/Documents/Books/Economics-Climate-Change-SEA/PDF/Economics-Climate-Change.pdf>.

-. Reponse from the Tatmadaw (Myanmar Armed Forces). 2011. 1 July 2011 <www.aseanpostnargiskm.org/response-to-nargis/national-response/tatmadaw-myanmar-armed-forces>.

Change, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate. IPCC Climate Change 2007:Working Group II:Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. 25 June 2011 <www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data_ar4/wg2/en/ch10.html>.

Children, Save the. News Update: About 40 percent of dead or missing in Burma Cyclone are children. 8 May 2008. 26 June 2011 <www.savethechildren.net/alliance/media/newsdesk/2008_05_08.html>.

FAO. FAO's Role in the 2008 Cyclone Nargis Flash Appeal for Myanmar. May 2008. 25 June 2011 <www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/tc/tce/pdf/myanmar_fao_proposals_pdf>.

Lean, Geoffrey. "Mangroves would have protected villagers." The Independent 11 May 2008.

Ozerdem, Alpaslan. "The Responsibility to Protect in Natural Disasters: Another Excuse for Interventionism? Nargis Cyclone, Myanmar." Conflict, Security and Development 10:5 (27 October 2010): 693-713.

Ploughshares. Burma-Myanmar (1988) . March 2011. 24 June 2011 <www.ploughshares.ca/content/burma-myanmar-1988-first-combat-deaths#Parties>.

Protect, International Coalition for the Responsibility to. Paragraphs 138-139 of te World Summit Outcome Document. 1 July 2011 <www.responsibilitytoprotect.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=398>.

Selth, Andrew. "Even Paranoids Have Enemies Cyclone Nargis and Myanmar's Fear of Invasion." Contemporary Southeast Asia Vol 30 issue 3 (2008): 379.

State, US Department of. US Department of State 2010 Human Rights Report: Burma. 2010. 29 June 2011 <www.state.gov/g/dr/r/s/hrrpt/2010/eap/154380.htm>. US Department of State Burma (Myanmar) Country Specific Information. 30 June 2011 <travel.state.gov/travel/cis_pa_tw/cis/cis_107.htm/#country>.

Steinberg, Professor David I. "Transcript: Outposts of Tyranny." The Washington Post 22 April 2005.

USAID. USAID Burma-Cyclone Fact Sheet #6 Fiscal Year (FY) 2008. 13 May 2008. 25 June 2011 <http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/humanitarian_assistance/disaster_assistance/countries/burma/template/fs_sr/fy2008/burma_cy_fs06_05-13-2008.pdf>.

USAID Responds to Cyclone Nargis. 4 June 2009. 29 June 2011 <www.usaid.gov/locations/asia/countries/burma/cyclone_nargis/>.

World Food Programme. Cyclone Nargis: Two Months Later. 3 July 2008. 27 June 2011 <www.wfp.org/stories/cyclone-nargis-two-months-later>.

Myanmar Emergency Operation (EMOP) 10749.0 Food Assistance to Cyclone Affected Populations in Myanmar. 2008. 25 June 2011 <www.wfp.org/operations/current_operations/project_docs/107490.pdf>.

World Food Programme Food Production Satisfactory in Post-Nargis Myanmar, But Access to Food Difficult for Many. 28 January 2008. 30 June 2011 <www.wfp.org/news/news-release/food-production-satisfactory-post-nargis-myanmar-access-food-difficult-many>.

World Food Programme Myanmar: Carving out humanitarian space post-Nargis. 24 May 2010. 25 June 2011 <www.wfp.org/content/myanmar-carving-out-humanitarian-space-post-nargis>.