1. Abstract

The conflict in Darfur is popularly known as an egregious humanitarian crisis and horrific ethnic conflict between Arab and Black Africans. On the surface, the conflict appears to be fueled by ethnic tensions and racism; however, there are multiple factors which escalated preexisting tensions into the complicated and violent situation which exists today. Ecological change in the form of cyclical drought and desertification is one of the few agreed upon sources of the conflict. As a result of reoccurring droughts throughout the 1980s, competition over diminishing fertile land and water contributed to tribal conflict and social unrest in Darfur, and ultimately a massive humanitarian crisis. Mounting frustration of decades of economic and social marginalization finally erupted into a full scale conflict in February of 2003 when rebel organizations successfully attacked Sudanese military posts in Darfur. The ongoing crisis in Darfur is commonly described as an ethnic conflict; however, the diminishing accessibility of natural resources, mainly water and land, and the desertification of the western most region of Sudan contributed to the escalation of a massive regional humanitarian crisis.

2. Description

A Human Face to the Tragedy

All too frequently reports appear in the media describing indiscriminate human right abuses and massacres committed against civilians in Darfur. We constantly see ghastly images portraying overcrowded refugee camps, starved children and armed militias; but, these images alone do not suffice to describe the fragility and gravity of the situation. Journalist and academic, Samantha Power, sheds some light on the human experience and suffering in the New Yorker article, "Dying in Darfur", by putting a human face and name to the hundreds of thousands of people killed and displaced in Darfur. She describes the experience of Amina Akajer Mohammed, a woman from Darfur's Zaghawa tribe. As of 2004, Amina was living in a refugee camp in Northern Chad where thousands of other Darfuris remain externally displaced. Amina's village was burned to the ground and many of her family members killed by Sudanese soldiers and Arab militiamen, called the janjaweed (Power 2004).

On January 31st, Amina's husband was away visiting his family. Not long

after dawn, when Amina and Mohammed [Amina's oldest son] arrived at the wells,

they heard the sounds of approaching planes. Fifteen minutes later, Amina recalled,

the aircraft began bombing the area around the wells, where a group of her

neighbors had also gathered. She and Mohammed were separated, as she fled with

a few of the family's donkeys, he [Mohammed] tried to assemble their panicked sheep.

According to Amina, dozens of people and hundreds of animals were killed in

the onslaught.

In the wake of the planes came Sudanese soldiers, packed into trucks and Land

Cruisers; they were followed by hundreds of menacing janjaweed on camelback

and horseback... When Amina saw the janjaweed approaching, she hurried the

donkeys to the red-rock hillock three hundred yards away. She assumed that

Mohammed had fled in another direction, but she turned and saw that he had

remained at the wells... He and the others were surrounded by several hundred

janjaweed. As the [of janjaweed militiamen] circle closed around her son, she ducked behind the hillock

and prayed. (Power 2004) |

Before continuing with the story of Amina and her son, an understanding of

the historical context will provide a better picture of this complex conflict.

Historical Context

Darfur has a rich history of civilization dating back to the 14th century rule of the Tunjur sultanate; it was the Tunjurs who first introduced Islam to the region. Following the Tunjur rule, the Keira dynasty controlled and governed the region. During this time, Darfur enjoyed relative independence from outside influence and colonial rule. There are two main historical events which laid the foundation for conflict in Dafur: the first is the legacy of British-Egyptian colonial imperialism, and the second being the residual impact of Libya's Colonel Gaddafi's pan-Arab movement of the 1980s.

It was not until the late 19th century that the Anglo-Egyptian imperialists- Egypt at this time was a British colony- ended the Keira dynasty's rule in Darfur (O'Fahey 2006). Initially, the British were not interested in the Sudan, and it was not until 1898 that they officially established Anglo-Egyptian colonial rule to preserve British regional dominance in North-Eastern Africa over the French (O'Fahey 2006). During this time, the British allowed Darfur de jure autonomy until 1917 when they invaded and incorporated Darfur into Sudan (O'Fahey 2006). Darfur remained politically marginalized and economically underdeveloped throughout the period of British colonialism. This political and economic neglect continued even after Sudan gained independence in 1956, and continues to be the main grievance of the people of Darfur and, particularly, the rebel movements like the SLM/A and JEM today.

Darfur's neighbors, especially Libya, have played a meddlesome role in Dafur. In the 1970s and 1980s, Libya's Colonel Gaddafi dreamed of establishing an Arab belt across the Sahelian Africa. Gaddafi planned to gain political influence over Chad, which would aid in the eventual 'Arabization' of the region. In an attempt to spread his pan-Arab agenda, Gaddafi launched a succession of military adventures in Chad. Gaddafi organized and armed discontented Sahelian Arabs; these Arabs formed the Islamic Legion which conducted Gaddafi's offenses in the region (de Waal 2004). From 1987 to 1989, Chadian factions backed by Libya used Darfur for refuge and as a base of operation; the factions resided in Darfur and relied heavily on the crops and cattle of the native Darfuri tribes (de Waal 2004). Gaddafi's influence had two destabilizing effects in Darfur: 1) many of the guns in Darfur today came from Gaddafi's factions and 2) Gaddafi’s pan-Arabism created an artificial Arab and Africa racial dichotomy. Pan-Arab sentiment led to the racial polarization of Darfur’s tribes along Arab and Black African lines. Arabism and Africanism continued to be used a political tool to mobilize people around a particular cause. Race and ethnic identity in Darfur is not so cut and dry, and the idea of an African-Arab dichotomy is historically and anthropologically bogus (de Waal 2005). Sudan expert, Alex de Waal, states in many publications that Darfur's Arabs are just as black, indigenous, Muslim and African as their non-Arab neighbors, but race has been used as a political tool to serve political agendas (de Waal 2005).

Tribal Composition of Darfur

Darfur's population is commonly referred to as a mosaic of tribes; in fact,

there are as many as eighty tribes who call Darfur home. Darfur, which is about

the size of France or the state of Texas, has a population of roughly 7.4 million

(Dagne 2006). The largest tribe is the Fur, which is a tribe of settled, subsistence

farmers. The Fur identify as Black African; other tribes which identify as

African are the Zaghawa nomads, Meidob, Massaleit, Dajo, Berti, Kanein, Mima,

Bargo, Massaleit and Tunjur (Dagne 2006). Many of these tribes are sedentary

farmers and reside mainly in the southern region of Darfur (O'Fahey 2006).

The Fur

is the main tribe associated with the currently active rebel organization,

the

Sudanese Liberation Movement (SLM) (Dagne 2006). The northern zone of Darfur

is inhabited mostly by camel and cattle nomads; the Zaghawa and Bedeyat, as

mentioned above, are camel herders, but identity as Black African. The predominately Arab and cattle herding tribes are the Rizeigat, Habbaniya,

Beni Halba, Taaisha and Maaliyya.

The Connection: Environmental Degradation and Civil War

The Cyclical Trend of Drought: Disrupting the Balance of Livelihoods

The economy of western Sudan has been and still is largely agrarian. Before drought and civil conflict plagued the region, Darfur operated by three major agricultural systems: sedentary rain-fed agriculture, sedentary irrigated agriculture and nomadic pastoralism (Robinson 2004). The ecological balance which once existed between sedentary agriculture and nomadic pastoralism suffered as repeated periods of drought led to desertification and environmental degradation. Rainfall patterns changed, leading to a decline in rainfall intensity and rainfall duration (Braun 2006).

The economy of western Sudan has been and still is largely agrarian. Before drought and civil conflict plagued the region, Darfur operated by three major agricultural systems: sedentary rain-fed agriculture, sedentary irrigated agriculture and nomadic pastoralism (Robinson 2004). The ecological balance which once existed between sedentary agriculture and nomadic pastoralism suffered as repeated periods of drought led to desertification and environmental degradation. Rainfall patterns changed, leading to a decline in rainfall intensity and rainfall duration (Braun 2006).

Reoccurring periods of drought and environmental degradation have become major obstacles in Sudan, especially in the western, rural region of Darfur. These periods of drought are cyclical, a trend which started in the mid-1980s. Since the devastating impact of drought and famine in 1984/85, Sudan has suffered from drought in 1989, 1990, 1997 and 2000 (Morrod 2003). Consecutive periods of drought brought crop failure and loss of livestock and pastureland (Morrod 2003). Changes in rainfall patterns in the last twenty years resulted in the decline of rainfall intensity and shortened the duration of rainfall; the rainy season, which normally lasted from May through September, shortened to the months of June through August (Bonde 2005).

The southward encroachment of the desert, desertification, presents a serious threat to the livelihoods of the existing farming and nomadic communities. Environmentalists and the humanitarian community attribute reoccurring drought and desertification as the main factors instigating conflict in Darfur. The phenomenon of cyclical drought has affected the entire Sahe; one in every five years is dry, resulting in agriculture collapse, migration of people and, thus, increasing the probability of conflict over limited food, land and water resources (Morrod 2003).

The Balance of Inter-Tribal Livelihoods

Historically, the nomadic tribes, like the Rizeigat, resided in the drier northern reaches of Darfur and traveled with their animals south into the more temperate southern farmlands during the dry season (Bonda 2005). They would then migrate back north with the onset on the rains; but with water holes and seasonal rivers vanishing, the nomads gradually ventured farther south searching for fertile land to pasture (Bonda 2005). Before the droughts in the 1980s, the nomadic and farming tribes relied on one another, and their families intermarried, but eventually conditions deteriorated (de Waal 2004). Many of the nomads settled into a semi-pastoral existence, establishing permanent villages amid the farming communities, the Fur, Masalit and Tunjur (Malek 2005). During periods of drought, the dramatic decrease in rainfall enabled Darfur's farming community to produce local crops, resulting in a substantial decrease in the food supply (Bilsborrow 1990). The nomadic populations also suffered because their livestock died from the lack of available water. Evidently, the southern regions of Darfur were overpopulated and the available natural resources stretched. With increasing competition over the diminishing pool of natural resources- water, grassland, arable soil- conflicts increased.

Without a system to address the growing disputes over land and water, the tribes started to defend their own communities and conducted reprisal raids on their foes (Anderson 2004). Clashes became increasingly common throughout the 1980s and 1990s. The Sudanese government failed to suppress the conflict because they were already deeply involved in preventing the growing separatist's movement in southern Sudan.

The Conflict

With many different tribes calling Darfur home, inter-tribal conflict was frequent, but these conflicts were usually solved by tribal leaders. Darfur's tribes coped with inter-tribal tensions and conflicts through traditional inter-communal negations. The elders of the tribes would convene to negotiate and mediate a settlement between disputing individuals (Malek 2005). By the mid-1980s, this system of traditional mediation began to disintegrate once the Sudanese government began to exert greater control over country’s nearly autonomous tribes in Darfur (Malek 2005). The government replaced the tribal councils with government programs to govern, but these programs did not fairly manage or mitigate disputes. Because Arabs dominated the government, disputes between Arabs and Black Africans were usually ruled in favor of Arab tribes (Malek 2005). Disputes over resources continued to increase and there was not a legitimate system to resolve them. Without a system to deal with growing land and resource disputes, the tribes of Darfur took matter into their own hands to defend their own communities and access to diminishing land and water resources (Anderson 2004).

Rebel Groups

Civil war officially erupted in Sudan's western region of Darfur in February 2003 as rebel organizations, such as the Sudanese Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), launched successful attacks against the government's airbase and military stock piles in Darfur. The SLM attacked a government airport, destroying fighter planes and killing 100 soldiers (Dagne 2006).The Sudanese Liberation Army and the Justice and Equality Movement claim that the government of Sudan discriminates against Muslim African ethnic groups in Darfur and has systematically targeted these ethnic groups since the 1990s (Dagne 2006). The central government in Khartoum has used divide-and-rule tactics and has chiefly sided with the Arab tribes to gain political control of the isolated region. Khartoum responded to the rebel activity by the SLM by supplying rival tribal groups with weapons (de Waal 2006). The Sudanese government exploited the already polarized and fragile environment in Darfur between the tribes. Predominately Arab tribes formed the Janjaweed militia; they continue to be supplied with arms and given government authorization to take care of the rebel groups, though this is the unofficial stance of the Sudanese government. Thousands of people lost their lives and roughly 2.5 million people either took refuge in neighboring Chad or became internally displaced persons (IDPs) (Malek 2005).

Civil war officially erupted in Sudan's western region of Darfur in February 2003 as rebel organizations, such as the Sudanese Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), launched successful attacks against the government's airbase and military stock piles in Darfur. The SLM attacked a government airport, destroying fighter planes and killing 100 soldiers (Dagne 2006).The Sudanese Liberation Army and the Justice and Equality Movement claim that the government of Sudan discriminates against Muslim African ethnic groups in Darfur and has systematically targeted these ethnic groups since the 1990s (Dagne 2006). The central government in Khartoum has used divide-and-rule tactics and has chiefly sided with the Arab tribes to gain political control of the isolated region. Khartoum responded to the rebel activity by the SLM by supplying rival tribal groups with weapons (de Waal 2006). The Sudanese government exploited the already polarized and fragile environment in Darfur between the tribes. Predominately Arab tribes formed the Janjaweed militia; they continue to be supplied with arms and given government authorization to take care of the rebel groups, though this is the unofficial stance of the Sudanese government. Thousands of people lost their lives and roughly 2.5 million people either took refuge in neighboring Chad or became internally displaced persons (IDPs) (Malek 2005).

The causes of this civil war can be summarized by what the two main rebel movements demand. Both the SLM and JEM platforms reflect the grievances of a people systematically marginalized from the political processes and living in a region of total social and economic insecurity (Bonda 2005).

The Actors |

Leadership |

Tribal Afficilation |

| SLM (Sudanese Liberation Movement) |

Minni Arcua Minnawi |

Fur |

| JEM (Justice and Equality Movement) |

Khalil Ibrahim |

Zaghawa |

| Janjaweed |

Musa Hilal |

Perdominately Baggara |

| Khartoum (Sudanese Government) |

President Omar al Bashir |

Arab |

The Conflict Today: More than the Environment

Environmental degradation and drought provided a ripe environment for conflict in Darfur, but this complex conflict cannot be accurately understood solely through an environmental perspective. Environmental degradation significantly contributed to and initiated the conflict in Darfur; but today many describe the conflict as a crisis of identity. It is false to suggest that Darfur’s tribes can be clearly distinguished or divided in terms of Arab and Black racial decent. The tribal ethnicity is not clear-cut given the long history of inter-marriage between indigenous non-Arab and Arab tribes (de Waal 2006). Rather, the identity of these tribes can be more accurately distinguished in terms of their livelihoods as either sedentary farmers or nomadic camel herders. Even though this case study analyzes the environmental factors resulting in the current civil war, disregarding the component of ethnic identity and the political manipulation of identity by the Islamic/Arab Sudanese government to serve their political agenda would undermine an accurate understanding of the conflict. More importantly, neglecting this piece undermines the ability to form effective and sound policies to negotiate peace in Darfur.

A Failing Peace Agreement

Since 2003, the Sudanese government and Darfur’s rebel groups have been in and out of negating on peace agreements, but each agreement and cease-fires has so far failed to establish lasting stability and peace. In September 2003, the government of Sudan and the SLA signed a cease-fire agreement mediated by President Idriss Deby of Chad, but this agreement collapsed in December 2003 (Dagne 2006). Following this first agreement, a series of attempted peace arrangements attempted to settle the conflict. The international community has pressured the Sudanese government to hold up on their end of the agreements, but attacks by the pro-government militia, Janjaweed, have been confirmed by the cease-fire commission established under the April Accord (Dagne 2006). Finally, in 2005, the SLA, JEM and the Sudanese government returned to the negotiating table in Abuja, Nigeria (Dagne 2006). This process, like the previous agreements, was stalled for days and failed to reach a comprehensive and effective peace agreement. The rebel factions and Darfur’s population at large are so deeply divided, ethnically and politically, that they are almost incapable of presenting a united front, while the Sudanese government has no reason to reach a settlement anytime soon (O’Fahey 2006).

The Darfur Peace Agreement was signed on May 5, 2006, but most argue that this agreement was inherently incomplete and asymmetric, meaning the negotiating terms and situation between the Sudanese government and the rebel groups were unfair from the moment both parties came to the negotiating table. The peace negotiation was constrained by two factors, according to Alex de Waal: 1) a mutual distrust, hatred and little confidence between the parties and 2) constraint from the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) which was signed by the Sudanese government and the Sudanese People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) which ended the twenty year civil war between northern and southern Sudan.

"President George W. Bush welcomes Sudanese Liberation Movement leader Minni Minnawi to the Oval Office Tuesday, July 25, 2006, in Washington, D.C., meeting to discuss the Darfur region of western Sudan."

3. Duration

Civil War: February, 2003 - Present

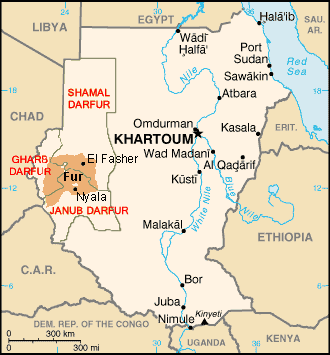

4. Location: Middle East/Africa

Sudan: Northern Africa, bordering the Red Sea, between Egypt and Eritrea

Darfur: Western Sudan, bordering Central Sudan to the east, Chad to the West, Central African Republic to the South, and Libya and Egypt bordering the northern region of Dafur

5. Actors

Sudanese Government (National Islamic Front), Janjaweed, Sudanese Liberation Army/Movement (SLA/M), Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), African Union, Regional State Actors (Chad, Eritrea, Ethiopia), United States, United Nations, European Union

6. Type of Environmental Problem

Drought Cycles and Desertification

One of the few agreed upon explanations of Darfur’s conflict is environmental degradation: consecutive periods of severe drought in northern and eastern Africa during the 1980s and 1990s. Drought is a crippling, life-threatening force, which creates a devastating cycle of environmental collapse, conflict and displacement. It is this cycle, coupled with the systematic political marginalization and neglect of Darfur by the Sudanese government, which escalated Darfur into civil war in 2002 (Morrod 2003). The section entitled Description describes in further detail the correlation between desertification and drought cycles and civil war.

Deforestation

In addition to the phenomenon of desertification and drought, the increase in population and live stock and the expansion of agriculture placed additional stresses on the environment. Deforestation became a serious problem as demand for wood and charcoal increased in the rain rich region of Darfur. Land has been cleared for agriculture and settlement which has put additional stress on the environment (Bilsborrow 136). The decline in tree and bush cover reduced the soil productivity and promoted erosion, soil depletion and salinization (Bilsborrow 136).

7. Type of Habitat

Dry

The western region of Sudan is generally characterized as arid, but the climate in Darfur ranges from tropical semi-arid in the north to tropical semi-humid in the south (Robinson 2004). Darfur’s environment ranges from semi-arid to tropical and semi humid, but most the population is concentrated around available water sources (Bilsborrow 136). The environment of the eastern region of Darfur is covered with plains and low hills of sandy soils and sandstone hills; this region is mainly waterless. The northern region of Darfur is desert, the Sahara, and years may pass without any rainfall. As opposed to the eastern and northern regions of Darfur, the west Darfur is covered with basement rock, a thin layer of sandy soil (Bilsborrow 136). This soil is too infertile to be farmed, but provides sporadic forest and vegetation that can be grazed by animals. The temperate climate called the Marrah Mountains is a region of relatively high rainfall and permanent springs of water (Bilsborrow 136). In this region, annual average rainfall is 700 mm and many trees remain green year-round.

8. Act and Harm Sites

(1) Sudan and It's Neighbor: Chad

This conflict in Darfur is predominately a Sudanese conflict. Though neighboring countries, such as Chad, have experienced the spilling effects of displaced persons, the conflict mainly resides within Sudan's sovereign borders. This is a conflict in which the Sudanese government, ideally with the support of Sudan’s neighbors and international community, will formulate a sound and comprehensive policy to grapple with the environmental implications of the conflict and to finally create political stability and security in the region.

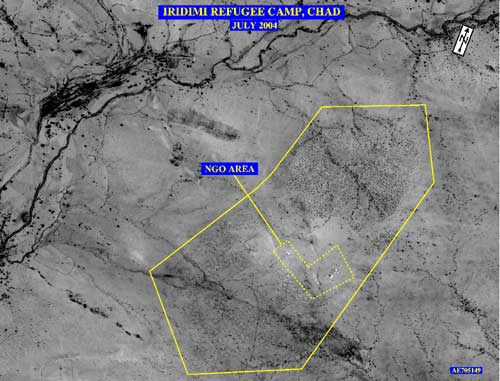

Satellite Image of Refugee Camps in Chad, 2004

9. Type of Conflict: Civil

The conflict in Darfur is most commonly characterized as a civil war; but like many civil wars, this conflict has local, regional and international implications. The beginning of the conflict began in the mid 1980s due, in part, to reoccurring droughts and environmental degradation; but, civil war, instigated by rebel activity, did not officially erupt until 2003. The Sudanese Liberation Movement (SLM) and the Justice Equality Movement (JEM) are the two most active rebel groups in the region; but it was the SLM who initiated the first attack against the Sudanese government (Brea 2005). The insurgency of rebel organizations met mass retaliation from the Sudanese government, as the Sudanese government characterized the SLM and JEM as terrorist organizations. The government in Khartoum used the same tactic they used to suppress the separatist's movements in the south by funding and supporting local rebel organizations to combat the growing threat of the JEM and SLM/A. Khartoum sponsored, and continues to sponsor, the Janjaweed militia to combat dissident groups. The Janjaweed have since committed indiscriminate violence and atrocities against the civilian population in Dafur.

Darfur's civil war continues to destabilize the region, and further destabilize the entire country which struggles to remain united. Stability in the southern region of Sudan remains in a fragile state as the separatist's movement and the southern region of Sudan wait to vote on a referendum to succeed from the country. There is additional regional instability developing in the eastern region of Sudan. The current and unresolved conflict in Darfur is perceived as a threat to the stability and unification process in Sudan as a whole.

Civil war in Darfur also threatens the stability of neighboring countries. The mass exodus of 2.2 million refugees poses complex security and humanitarian challenges for Sudan's neighbors, particularly Chad (New Scientist 2006). Chadian villagers living across the border struggle to survive, and the influx of starving Sudanese refugees have placed many Chadians in severe risk of food shortages and insecurity (Brea 2005). The Janjaweed from Sudan are known to enter Chad in order to attack refugee camps along the border and Chadian villages, further destabilizing the region (Brea 2005).

Despite the a recent peace agreement, the Darfur Peace Agreement (DPA), the conflict proceeds and the Sudanese central government refuses to allow UN peacekeeping troops into the country to establish security in the region (Braun 2006). President Omar Hassan El-Bashir has refused to accept United Nations troops to intervene in the Darfur region, and the African Union has been ineffective in the region because of the limited mandate and resources.

10. Level of Conflict: High

In only three years, hundreds of villages have been destroyed and 2.2 to 2.5 million Darfurians are internally and externally displaced (New Scientist 2006). It is difficult to gather and find accurate data regarding mortality rates due to the ongoing nature of the civil war, along with the Sudanese government’s refusal to cooperate and admit the humanitarian organizations and the international community to aid in the conflict. Current estimations of the fatality rate suggest the death toll ranges from 200,000 to 500,000 (New Scientist 2006). Initially, the World Health Organization issued a report in 2004 estimating that 70,000 people had perished over a seven-month period because of the Darfur conflict (WHO 2004). By April 2005, the United Nations humanitarian coordinator estimated 180,000 people died over 18 months, and UN Secretary General Kofi Annan had put the number at 300,000 (New Scientist 2006). New analysis conducted by Hagan and Palloni found that hundreds of thousands of people have died in the conflict, rather than the earlier reports of tens of thousands. They extended their estimate to over a 31 month period, up to May 2006, and they found the death toll ranging from 170,000 to 255,000 (New Scientist 2006).

In only three years, hundreds of villages have been destroyed and 2.2 to 2.5 million Darfurians are internally and externally displaced (New Scientist 2006). It is difficult to gather and find accurate data regarding mortality rates due to the ongoing nature of the civil war, along with the Sudanese government’s refusal to cooperate and admit the humanitarian organizations and the international community to aid in the conflict. Current estimations of the fatality rate suggest the death toll ranges from 200,000 to 500,000 (New Scientist 2006). Initially, the World Health Organization issued a report in 2004 estimating that 70,000 people had perished over a seven-month period because of the Darfur conflict (WHO 2004). By April 2005, the United Nations humanitarian coordinator estimated 180,000 people died over 18 months, and UN Secretary General Kofi Annan had put the number at 300,000 (New Scientist 2006). New analysis conducted by Hagan and Palloni found that hundreds of thousands of people have died in the conflict, rather than the earlier reports of tens of thousands. They extended their estimate to over a 31 month period, up to May 2006, and they found the death toll ranging from 170,000 to 255,000 (New Scientist 2006).

11. Fatality Level of Dispute: (military and civilian fatalities): 450,000 (estimated)

Since the conflict began is 2003, the estimated death toll (as of April 30, 2006) now exceeds 450,000 Darfurians, mostly due to starvation (Sudan Watch 2006). Due to the on going nature of the conflict and the instability in region, accurate information and data collection regarding the level of fatality among civilians and the military does not exist. The Sudanese government continues to refuse compliance with international governmental and nongovernmental humanitarian organizations; this has greatly undermined the efforts to conduct a reliable survey of the civilian and military fatality near impossible.

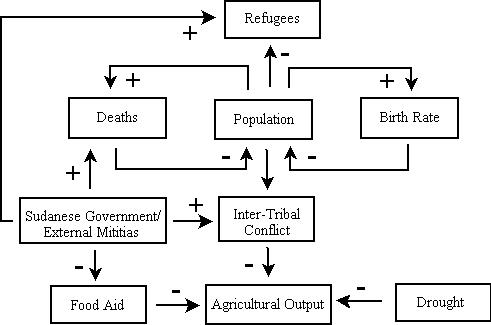

12. Environment-Conflict Link and Dynamics

13. Level of Strategic Interest: Regional

Regional: Darfur's conflict has mainly impacted the region and Sudan’s neighbors, primarily Chad, but the conflict has claimed much international attention in the last couple of years. The United States, United Nations and African Union are deeply involved in the comprehensive peace process to end the humanitarian crisis in Darfur. This has transformed a regional conflict into a pertinent and prominent international issue.

14. Outcome of Dispute

Since the Darfur Peace Agreement did not successfully bring the disputing parties to settle, civil war and the humanitarian crisis in Darfur and Chad continues as of the beginning of December 2006. Even though the Sudanese government and the rebel groups have been in and out of peace talks since the inception of the violence, many people are skeptical that an end to this conflict is in the near future. This skepticism derives from the fact that the Sudanese government continues to be reluctant to cooperate with the United Nations, African Union and international community and the SLM and JEM remain fragmented with unclear demands.

And What Ever Happened to Amina and Mohammed?

"By nightfall, the sounds of gunfire and screaming had faded, and Amina furtively returned to the wells. She discovered that they were stuffed with corpses, many of which had been dismembered. She was determined to find her son, but also hoped that she wouldn't. Rummaging frantically around the wells by moonlight, she say the bodies of dozens of people she knew, but for a long time she was unable to find her son.

Suddenly, she spotted his face- but only his face. Mohammed had been beheaded. " (Power 2004). |

15. Related ICE and TED Cases

Rwanda and Conflict

Eritrea and Ethiopia

Nile River Dispute

Civil War in Sudan, Human Price for Oil

Sahara Dispute and Environment

Sudan and Civil War and Religion

16. Relevant Websites and Literature

Bilsborrow, Richard E. and Pamela F. DeLargy. “Land Use, Migration and Natural

Resource Deterioration: The Experience of Guatemala and the Sudan,” Population and Development Review, Vol. 16 (1990), pp. 125-147.

Bond, Sandslous Tombe. “Darfur and Water Management Issues,” (Sept. 2005),

http://www.netwas.org/newsletter/articles.2005/09/2

Braun, Josh. “A Hostile Climate: Did Global Warming Cause a Resource War in

Darfur?” SeedMagazine.com (Aug. 2006).

Brea, Jennifer. The Making of a Genocide. World News. www.worldnews.about.com/od.sudan/ig/Darfur (2005).

Cohen, Roberta. "No Quick Fix for Darfur," Northwestern Journal of International

Affairs (Spring 2006)

http://www.brook.edu/fp/projects/idp/articles/200606_RC_NJIA_Darfur.pdf

De Waal, Alex. "Counter-Insurgency on the Cheap," London Review of Books. Vol. 26, No. 15, (August 2005).

De Waal, Alex. "Darfur Peace Agreement: So Near, So Far," OpenDemocracy, (September 29, 2006).

De Waal, Alex. "Darfur's Deep Grievances Defy All Hope for an Easy Solution," Guardian, (July 25, 2004).

De Waal, Alex. "Tragedy in Darfur: On Understanding and Ending the Horror," Boston

Review. (October/November 2004). http://www.bostonreview.net/BR29.5/dewaal.html

De Waal, Alex. "Victims of Genocide," ZNet Activism. (February 2005).

Malek, Cate. “Annotated Conflict Cases: The Darfur Region of the Sudan,” (July 2005),

http://www.beyondintractability.org/case_studies/Darfur.jsp?=5101

O'Fahey, Rex Sean. "Does Darfur Have a Future in Sudan?" Fletcher Forum of World

Affairs (Winter 2006). http://fletcher.tufts.edu/forum/30-1pdfs/ofahey.pdf#search=%22does%20darfur%20have%20a%20future%20in%20sudan%22

Power, Samantha. "Dying for Darfur," The New Yorker (August 30, 2004). http://www.newyorker.com/printables/fact/040830fa_fact1

Robinson, Jonathan. “Desertification and Disarry: the Threats to Plant Genetic Resources

of Southern Darfur, Western Sudan,” Plant Genetic Resources, Vol. 3(1) (2004), pp. 3-11.

The Root Cause of the Darfur Conflict: A Struggle Over Controlling an Environment that Can No Longer Support all the People Who Must Live on It: The Sudan Watch. July 2006. http://sudanwatch.blogspot.com/

http://www.refugeesinternational.org/content/article/detail/3078?PHPSESSID=769850d3ec4ba3334e5e18d5a334a57b

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2006/09/060914-darfur-deaths.html

http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn10082-darfur-death-toll-appears-vastly-underestimated.html

The economy of western Sudan has been and still is largely agrarian. Before drought and civil conflict plagued the region, Darfur operated by three major agricultural systems: sedentary rain-fed agriculture, sedentary irrigated agriculture and nomadic pastoralism (Robinson 2004). The ecological balance which once existed between sedentary agriculture and nomadic pastoralism suffered as repeated periods of drought led to desertification and environmental degradation. Rainfall patterns changed, leading to a decline in rainfall intensity and rainfall duration (Braun 2006).

The economy of western Sudan has been and still is largely agrarian. Before drought and civil conflict plagued the region, Darfur operated by three major agricultural systems: sedentary rain-fed agriculture, sedentary irrigated agriculture and nomadic pastoralism (Robinson 2004). The ecological balance which once existed between sedentary agriculture and nomadic pastoralism suffered as repeated periods of drought led to desertification and environmental degradation. Rainfall patterns changed, leading to a decline in rainfall intensity and rainfall duration (Braun 2006).  Civil war officially erupted in Sudan's western region of Darfur in February 2003 as rebel organizations, such as the Sudanese Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), launched successful attacks against the government's airbase and military stock piles in Darfur. The SLM attacked a government airport, destroying fighter planes and killing 100 soldiers (Dagne 2006).The Sudanese Liberation Army and the Justice and Equality Movement claim that the government of Sudan discriminates against Muslim African ethnic groups in Darfur and has systematically targeted these ethnic groups since the 1990s (Dagne 2006). The central government in Khartoum has used divide-and-rule tactics and has chiefly sided with the Arab tribes to gain political control of the isolated region. Khartoum responded to the rebel activity by the SLM by supplying rival tribal groups with weapons (de Waal 2006). The Sudanese government exploited the already polarized and fragile environment in Darfur between the tribes. Predominately Arab tribes formed the Janjaweed militia; they continue to be supplied with arms and given government authorization to take care of the rebel groups, though this is the unofficial stance of the Sudanese government. Thousands of people lost their lives and roughly 2.5 million people either took refuge in neighboring Chad or became internally displaced persons (IDPs) (Malek 2005).

Civil war officially erupted in Sudan's western region of Darfur in February 2003 as rebel organizations, such as the Sudanese Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), launched successful attacks against the government's airbase and military stock piles in Darfur. The SLM attacked a government airport, destroying fighter planes and killing 100 soldiers (Dagne 2006).The Sudanese Liberation Army and the Justice and Equality Movement claim that the government of Sudan discriminates against Muslim African ethnic groups in Darfur and has systematically targeted these ethnic groups since the 1990s (Dagne 2006). The central government in Khartoum has used divide-and-rule tactics and has chiefly sided with the Arab tribes to gain political control of the isolated region. Khartoum responded to the rebel activity by the SLM by supplying rival tribal groups with weapons (de Waal 2006). The Sudanese government exploited the already polarized and fragile environment in Darfur between the tribes. Predominately Arab tribes formed the Janjaweed militia; they continue to be supplied with arms and given government authorization to take care of the rebel groups, though this is the unofficial stance of the Sudanese government. Thousands of people lost their lives and roughly 2.5 million people either took refuge in neighboring Chad or became internally displaced persons (IDPs) (Malek 2005).

In only three years, hundreds of villages have been destroyed and 2.2 to 2.5 million Darfurians are internally and externally displaced (New Scientist 2006). It is difficult to gather and find accurate data regarding mortality rates due to the ongoing nature of the civil war, along with the Sudanese government’s refusal to cooperate and admit the humanitarian organizations and the international community to aid in the conflict. Current estimations of the fatality rate suggest the death toll ranges from 200,000 to 500,000 (New Scientist 2006). Initially, the World Health Organization issued a report in 2004 estimating that 70,000 people had perished over a seven-month period because of the Darfur conflict (WHO 2004). By April 2005, the United Nations humanitarian coordinator estimated 180,000 people died over 18 months, and UN Secretary General Kofi Annan had put the number at 300,000 (New Scientist 2006). New analysis conducted by Hagan and Palloni found that hundreds of thousands of people have died in the conflict, rather than the earlier reports of tens of thousands. They extended their estimate to over a 31 month period, up to May 2006, and they found the death toll ranging from 170,000 to 255,000 (New Scientist 2006).

In only three years, hundreds of villages have been destroyed and 2.2 to 2.5 million Darfurians are internally and externally displaced (New Scientist 2006). It is difficult to gather and find accurate data regarding mortality rates due to the ongoing nature of the civil war, along with the Sudanese government’s refusal to cooperate and admit the humanitarian organizations and the international community to aid in the conflict. Current estimations of the fatality rate suggest the death toll ranges from 200,000 to 500,000 (New Scientist 2006). Initially, the World Health Organization issued a report in 2004 estimating that 70,000 people had perished over a seven-month period because of the Darfur conflict (WHO 2004). By April 2005, the United Nations humanitarian coordinator estimated 180,000 people died over 18 months, and UN Secretary General Kofi Annan had put the number at 300,000 (New Scientist 2006). New analysis conducted by Hagan and Palloni found that hundreds of thousands of people have died in the conflict, rather than the earlier reports of tens of thousands. They extended their estimate to over a 31 month period, up to May 2006, and they found the death toll ranging from 170,000 to 255,000 (New Scientist 2006).