| ICE Case Studies

|

The Impacts of Climate Change on the Mekong Delta by Katie Padilla |

I.

Case Background |

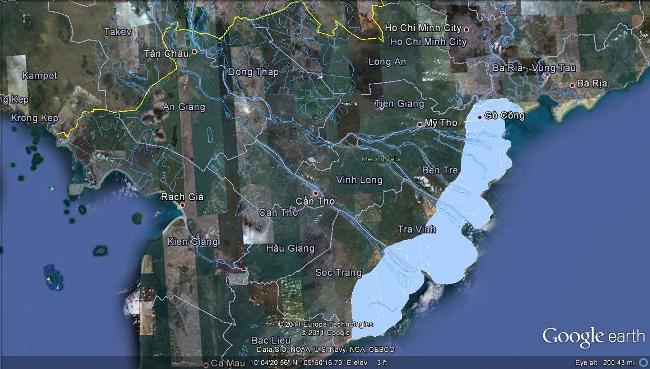

Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Source: NASA

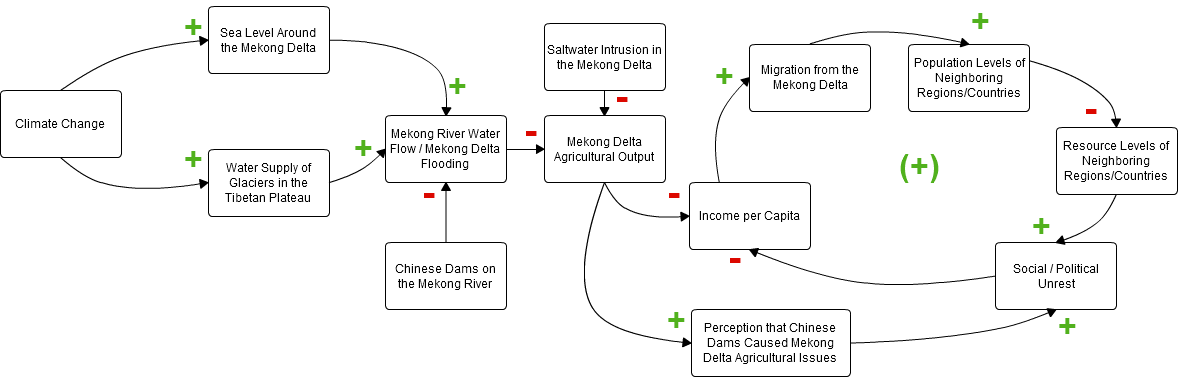

The Mekong Delta is critical to the livelihoods and food security of millions of people in Vietnam. 22% of the population of Vietnam lives in the Mekong Delta, which is a high population density area of about 17 million people (Yun). Agriculture is a primary source of livelihood in the Mekong Delta, where roughly half of the total amount of food in Vietnam is produced (ICEM, 7). A large volume of the agricultural output of the Mekong Delta is exported throughout Southeast Asia, making it a crucial agricultural source for other countries in the region as well (ICEM, 59). Climate change presents an increased flooding risk to the Mekong Delta due to rising sea levels near low lying land at the mouth of the delta, increased rainfall, and increasing water flow of the Mekong River resulting from glacial melt in the Tibetan Plateau, where its headwaters are located. The increased flooding risk along with increasing levels of saltwater intrusion in the Mekong Delta pose a real threat to its agricultural output. As a result of decreased agricultural output, income per capita in the Mekong Delta will likely fall. An eventual migration of residents of the Mekong Delta to neighboring regions of Vietnam and/or neighboring countries could occur due to their loss of livelihoods. This poses the potential for social and/or political unrest as resource shortages may affect the food security and livelihoods of the residents of the regions to which the Mekong Delta refugees may migrate.

Agricultural Importance of the Mekong Delta

The Mekong Delta is critically important to Vietnam’s national agricultural production. According to Can Tho University estimates, the Mekong Delta produces 50% of the nation’s rice, 80% of the nation’s fruit, and 60% of the nation’s fish, making it the largest agriculture and aquaculture production region in Vietnam (ICEM, 37). Overall, 46% of the total amount of food produced in Vietnam comes from the Mekong Delta (ICEM, 7). Agriculture is a crucial source of livelihood for the residents of the Mekong Delta, particularly rice cultivation, which is the primary livelihood for 60% of the inhabitants of the Mekong Delta (K k nen, 206).

The agricultural output of the Mekong Delta

supports the population of numerous other countries in the region in

addition to Vietnam’s population. According to a National Intelligence

Council (NIC) Conference Report from January 2010, Vietnam is the

world’s second largest rice exporter, and the Mekong Delta produces the

overwhelming majority of Vietnam’s rice exports (CENTRA Technology, Inc.

and Scitor Corporation, 14). “As well as being the “food basket” of

Vietnam, the Mekong Delta region also provides more than 80 per cent of

total rice exports – an important contribution to the food security

across the region” (ICEM, 59).

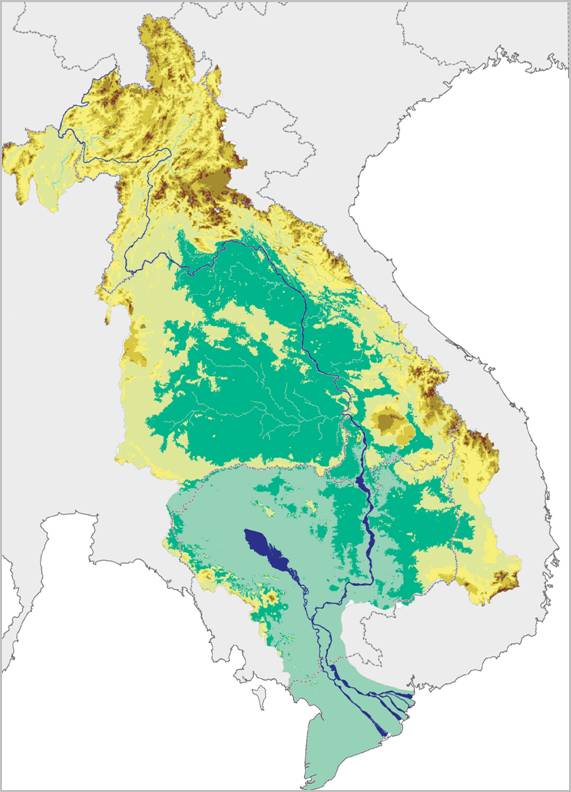

As illustrated in the land use map to the left from the Technical Support Division Mekong River Commission Secretariat, the Mekong Delta is a primary agricultural area in the region. Agricultural land constitutes 75% of the Mekong Delta, most of which is dedicated to rice paddies (K k nen, 206). Neighboring countries such as Cambodia and Laos, which are heavily forested as noted by the still intact forest lands shown in green, rely on the agricultural output of the Mekong Delta, as do numerous other countries.

The agricultural output of the Mekong Delta supports the population of numerous other countries in the region in addition to Vietnam’s population. According to a National Intelligence Council (NIC) Conference Report from January 2010, Vietnam is the world’s second largest rice exporter, and the Mekong Delta produces the overwhelming majority of Vietnam’s rice exports (CENTRA Technology, Inc. and Scitor Corporation, 14). “As well as being the “food basket” of Vietnam, the Mekong Delta region also provides more than 80 per cent of total rice exports – an important contribution to the food security across the region” (ICEM, 59).

The Mekong Delta represents the largest scale of irrigation areas in the region, and the high agricultural output of the Mekong Delta translates into a substantial source of economic output for Vietnam as well. The Mekong Delta contributes 27% of Vietnam’s GDP according to the 2009 Mekong Delta Climate Change Forum Report (ICEM, 59). As such, the agricultural output of the Mekong Delta is not only crucial to the food security of numerous countries in Southeast Asia, but also an important component of Vietnam’s GDP.

Environmental Impacts of Climate Change on the Mekong Delta

The Mekong Delta has historically faced seasonal

flooding threats as a result of annual monsoon rains. The “flooding

season” occurs in the Mekong Delta on an annual basis from July to

November (Nguyen, 6).  The major flood risk map from the Technical Support Division Mekong

River Commission Secretariat illustrates areas in the lower Mekong

region that are prone to flooding. The flood risk area highlighted in

light blue in the map represents the maximum historical flood extent

in the region based on an aggregation of the extent of the 1995, 1996,

and 2000 floods (Mekong River Commission, Technical Support Division).

As evidenced by the historical flooding illustrated in this map, it is

clear that the majority of the Mekong Delta is already at a high flood

risk. Climate change poses an even greater flooding threat to the

Mekong Delta as a result of rising sea levels near low lying land at the

mouth of the delta, increased rainfall, and an eventual increase in the

water supply at the Mekong River’s headwaters due to melting glaciers

in the Tibetan Plateau.

The major flood risk map from the Technical Support Division Mekong

River Commission Secretariat illustrates areas in the lower Mekong

region that are prone to flooding. The flood risk area highlighted in

light blue in the map represents the maximum historical flood extent

in the region based on an aggregation of the extent of the 1995, 1996,

and 2000 floods (Mekong River Commission, Technical Support Division).

As evidenced by the historical flooding illustrated in this map, it is

clear that the majority of the Mekong Delta is already at a high flood

risk. Climate change poses an even greater flooding threat to the

Mekong Delta as a result of rising sea levels near low lying land at the

mouth of the delta, increased rainfall, and an eventual increase in the

water supply at the Mekong River’s headwaters due to melting glaciers

in the Tibetan Plateau.

As described in detail in Section 6

below, climate change has already resulted in a substantial amount of

sea level rise near the delta as well as increased rainfall, average

temperatures, number of extreme weather events such as typhoons, and

saltwater intrusion in the Mekong Delta (ICEM, 4 – 5). Among the

climate change impacts experienced to-date, the Mekong Delta has

experienced a 30% annual increase in rainfall, shifting rainfall

patterns, an average temperature increase of 0.5 C in Can Tho (the

largest city in the Mekong Delta) over the last 30 years, and an average

sea level rise of 3 mm per year over the last 30 years in the waters

around the mouth of the delta (ICEM, 4 – 5). The average elevation of

the Mekong Delta is roughly five feet above sea level, which makes it

particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels (Yun).

Collectively, the impacts of climate change are

predicted to intensify in coming years, with projected increases in

average temperatures of 1.1 C to 3.6 C as compared to Vietnam’s average

temperature during the 1980‐1999 period (ICEM, 6). The average level of

Vietnam’s seas is predicted to rise by 28‐33 cm by 2050 and by 65‐100

cm by 2100 as compared to the 1980‐1999 period (ICEM, page 6).

The impacts of climate change on the glaciers in the Tibetan Plateau pose a threat to the Mekong Delta as well because the Mekong River’s headwaters are located there. According to a report by the Institute for Governance & Sustainable Development (IGSD) on the retreat of Tibetan Plateau glaciers, the level of warming of the Tibetan Plateau is about three times the global average and temperature increases of 0.3 C or more have occurred there each decade over the past 50 years (IGSD, 1). As the glaciers in the Tibetan Plateau continue to melt as a result of climate change, the flow of the Mekong River will increase as well, posing a greater flooding threat to the Mekong Delta in the short-term future. “Over the next century, the maximum flow of the Mekong is estimated to increase significantly, while the minimum monthly flows are estimated to decline, meaning increased flooding risks during wet season and an increased possibility of water shortage in dry season” (IGSD, 3). Eventually, once the glaciers in the Tibetan Plateau have fully melted, the flow of major Asian rivers such as the Mekong will decrease due to the loss of glacial run-off (Larmer, 4) In the short-term, the impacts of climate change in the Tibetan Plateau pose a greater flooding threat to the Mekong Delta (IGSD, 3).

Impacts of Climate Change on the Livelihoods of Mekong Delta Residents

Collectively, the projected impacts of climate change present a real threat to the agricultural productivity of the Mekong Delta, which will negatively impact the livelihoods of many of its residents due to the importance of agriculture to this region. According to one projection, 90% of the agricultural land in the Mekong Delta would be affected by flooding and 70% of the Mekong Delta will suffer from saline intrusion as a result of climate change (ICEM, page 6). The combined impacts of flooding and increased saltwater intrusion threaten the agricultural output of the Mekong Delta, particularly its rice production. According to one projection, the rice yield potential of the Mekong Delta will decline by up to 50% by the year 2100, which threatens the food security of Vietnam as well as the numerous countries that rely on its rice exports as described previously (ICEM, 69). Shifting rainfall patterns resulting from climate change will contribute to the predicted decrease in the Mekong Delta’s rice production.

With climate change, the summer‐autumn rice crop is likely to suffer from insufficient rainfall during land preparation and in the middle of the season and from too much water towards the end of the season. Comparisons between the 1980‐figures and estimations for 2030 show that the rainy season will start two weeks later, total rainfall will be 20% less and farmers have to pay more for pumping water. Adjusting and adapting the cropping calendar and pattern will be necessary (ICEM, 37).

A

large portion of the Mekong Delta could become uninhabitable as well if

the sea level rises substantially around the low-lying lands at the

mouth of the delta. According to one prediction in the 2009 Mekong

Delta Climate Change Forum Report, 25% of Can Tho province and 50% of

Ben Tre province would be completely inundated with water if the average

sea level rises by one meter during this century, while the Government

of Vietnam predicts that about 38% of the Mekong Delta’s entire current

land area would be inundated under the same scenario (ICEM, 6, 59). The

amount of people that could be impacted by coastal erosion is

staggering.

A

large portion of the Mekong Delta could become uninhabitable as well if

the sea level rises substantially around the low-lying lands at the

mouth of the delta. According to one prediction in the 2009 Mekong

Delta Climate Change Forum Report, 25% of Can Tho province and 50% of

Ben Tre province would be completely inundated with water if the average

sea level rises by one meter during this century, while the Government

of Vietnam predicts that about 38% of the Mekong Delta’s entire current

land area would be inundated under the same scenario (ICEM, 6, 59). The

amount of people that could be impacted by coastal erosion is

staggering.

By 2050, more than 1 million people in the Delta will be directly affected by increased coastal erosion and land loss, primarily caused by decreased sediment delivery by rivers due to upstream dams but also as a result of sea level rise and regular storms. Under sea level rise scenarios of 20 cm and 45 cm, permanent inundation would shift inland up to 25 km and 50 km respectively (ICEM, 7).

The area shaded in light blue in the Google Earth map illustrates the potential extent of the Mekong Delta that would be inundated if the coastline were to shift inland by 25 km as a result of rising sea levels. Threats of significant inundation of coastal lands and other impacts of climate change are exacerbated by the high population density of the Mekong Delta. The population of the Mekong Delta grew by 1.7 million people over the past decade and an estimated 5 million people could be affected by a one meter sea level rise, the majority of which are poor and work in the agriculture and fishing sectors, both of which are at risk due to climate change (ICEM, page 7). According to the 2009 Mekong Delta Climate Change Forum Report, poor people who work in these sectors and are concentrated in the coastal areas of the Mekong Delta will be among the first to be impacted by the increased flooding, saltwater intrusion, and extreme events predicted in the area (ICEM, 7). Collectively, millions of people living in the Mekong Delta will be impacted by climate change, either as a result of the projected decrease in the agricultural output of the region or due to inundation from rising sea levels.

Potential for Mass Migration and Conflict

As a result of the decreased agricultural output in the Mekong Delta, income per capita in this area will likely fall given the importance of agriculture to the region. Due to the loss of livelihoods as well as the potential for widespread inundation of currently populated areas as a result of rising sea levels, an eventual migration of the Mekong Delta’s residents to neighboring regions of Vietnam and/or neighboring countries could occur. The potential for a mass migration from the Mekong Delta is considered to be likely by some. According to a NIC Conference Report from January 2010, "Vietnam is the country at greatest overall risk for mass inland migration. The decimation of the Mekong Delta will push millions of Vietnamese north into Ho Chi Minh City and beyond into the Central Highlands, as well as over the border into Cambodia. A more generalized movement of ethnic Vietnamese from lowland to upland areas throughout the country will likely cause ethnic conflict or displacement of native ethnic minorities" (CENTRA Technology, Inc. and Scitor Corporation, 29).

The potential mass migration of residents of the Mekong Delta would increase the population levels of the regions to which the Mekong Delta refugees migrate, which could stress vital infrastructure for delivering water and sanitation services and possibly lead to an increased and unsustainable demand for resources. This poses the potential for social and/or political unrest as resource shortages may affect the food security and livelihoods of the neighboring regions. The potential for conflict is more likely if Mekong Delta refugees migrate to areas that are already resource constrained. According to a recent report on the security impacts of climate change in Southeast Asian cross-border areas, “fleeing environmental destruction may not necessarily result in violence, but when migrants encroach on the territory of people who may also be resource constrained, the potential for violence rises” (Ardiansyah and Putri, 8).

Mekong Delta refugees may migrate north within Vietnam, potentially to larger cities such as Ho Chi Minh City as suggested in the NIC Conference Report, or to neighboring countries such as Cambodia or Laos, although past animosity between the Vietnamese and Kmhers may result in ethnic and international conflict if Mekong Delta refugees attempt to migrate to Cambodia (CENTRA Technology, Inc. and Scitor Corporation, 47).

An additional factor that may result in conflict is

the construction of dams upstream on the Mekong River by China. Chinese

dams have been built on the Mekong River to deliver hydropower to fuel

its growing energy needs, which reduces the water flow of the Mekong

River to the Mekong Delta.

The Mekong River flow and overall hydrology is not only influenced by climate change. Many forms of development change and shape the natural patterns, especially the construction of hydropower dams upstream in the main Mekong River and its tributaries. For example, the existing and planned dams in Yunnan Province China and in Vietnam’s Central Highlands will take up to 80% of the sediment reaching the Delta with major implications for settlements and economic sectors, especially agriculture and fisheries (ICEM, 11).

Vietnamese may perceive Chinese dams as the cause for

the predicted decline in the Mekong Delta’s agricultural output, which

creates the potential for an international conflict between China,

Vietnam and other countries impacted by the Mekong Delta refugee

migration and corresponding resource shortages.

The impacts of climate change are already affecting the Mekong Delta, with substantial recorded increases in average temperatures and sea level rise occurring since the 1970’s. As the impacts of climate change intensify, conflict may occur as a result of a potential mass migration of individuals who have lost their livelihoods due to the declining agricultural productivity of the Mekong Delta and/or individuals that are forced to relocate as a result of rising sea levels. This poses the potential for social and/or political unrest as resource shortages may affect the food security and livelihoods of the residents of the regions to which the Mekong Delta refugees may migrate.

The timing of when such a migration may occur is open

to debate. Based on several predictions in the 2009 Mekong Delta

Climate Change Forum Report, climate change will have substantial

impacts on the Mekong Delta by the year 2050. The average level of

Vietnam’s seas is predicted to rise by 28‐33 cm by 2050 as compared to

the 1980‐1999 period (ICEM, page 6). More than 1 million people in the

Mekong Delta are predicted to be directly affected by increased coastal

erosion and land loss by 2050, with potential permanent inundation

shifting inland by 25 to 50 km (ICEM, 7). For purposes of this case

study, an estimated timeframe for conflict to occur as a result of a

migration of Mekong Delta refugees is from 2050 onward, coinciding with

several estimates of when climate change impacts are expected to

substantially intensify.

| Continent: | Asia |

| Region: | Southeast Asia |

| Countries: | Vietnam and potentially the neighboring countries of Cambodia, Laos, and China |

As illustrated in the area circled in red in the map to the left from the Perry-Casta eda Library Map Collection, the Mekong Delta is located at the southernmost tip of Vietnam and is the site at which the Mekong River empties into the South China Sea. It encompasses an area of 39,200 km2 and accounts for 12% of the national area of Vietnam and 5% of the entire Mekong Basin area (K k nen, 206). The population density of the Mekong Delta is 412 persons per km2, which is 1.75 times the nation’s average population density (K k nen, 206).

The potential conflict would occur in

the regions to which the Mekong Delta refugees migrate. The location of

the potential conflict is speculative at this point, but could occur in

other parts of Vietnam (likely north of the Mekong Delta in higher

elevation areas), or in neighboring countries such as Cambodia or Laos.

As stated previously, past animosity between the Vietnamese and Kmhers

may result in ethnic and international conflict if Mekong Delta refugees

attempt to migrate to Cambodia (CENTRA Technology, Inc. and Scitor

Corporation, 47).

It is also possible that a conflict with China may occur if the Vietnamese perceive Chinese dams as the cause for the predicted decline in the Mekong Delta’s agricultural output. This could create the potential for an international conflict between China, Vietnam and other countries impacted by the Mekong Delta refugee migration and corresponding resource shortages.

The residents of the Mekong Delta and the other regions of Vietnam and/or other countries to which they may migrate are the primary actors involved in this case study. The sovereign actors that would be involved in this potential conflict include Vietnam and possibly the neighboring countries of Cambodia, Laos, and China.

Current Impacts of Climate Change

Climate change has already substantially impacted the Mekong Delta, including rising sea levels near low lying land at the mouth of the delta, increased rainfall, an increased number of extreme weather events, increased average temperatures, and increased saltwater intrusion (ICEM, 4 – 5). The sea level around the Mekong Delta has risen by 20 cm since 1901, and data from the Vung Tau monitoring station in Vietnam indicates an average sea level rise of 3 mm per year over the last 30 years (ICEM, 4). The potential for additioanl sea level rise is particularly concerning given the low elevation of the Mekong Delta. The map below from MRC 2003 Social Atlas LMB Additional Maps shows the elevation of the lower Mekong Basin. The entire Mekong Delta is less than 100 meters above sea level as indicated by the light green shading, putting it at significant risk of inundation of low lying lands around the mouth of the delta in the event a substantial rise in the sea level occurs.

In addition to sea level rise, “the Mekong Delta has experienced

substantial increases in rainfall, as high as 177% during winter in Soc

Trang on the coast and a 30% annual increase” (ICEM, 4). The timing of

annual rainfall in the Mekong Delta has shifted as well. According to

the Delta Research and Global Observation Network (DRAGON) Institute at

Can Tho University, rainfall has increased at the end of the rainy

season over the last 10 years, but has decreased at the beginning of the

rainy season over the same period (ICEM, 4). Shifting rainfall patterns

such as this can have an adverse effect on the agricultural

productivity of the Mekong Delta.

In addition to sea level rise, “the Mekong Delta has experienced

substantial increases in rainfall, as high as 177% during winter in Soc

Trang on the coast and a 30% annual increase” (ICEM, 4). The timing of

annual rainfall in the Mekong Delta has shifted as well. According to

the Delta Research and Global Observation Network (DRAGON) Institute at

Can Tho University, rainfall has increased at the end of the rainy

season over the last 10 years, but has decreased at the beginning of the

rainy season over the same period (ICEM, 4). Shifting rainfall patterns

such as this can have an adverse effect on the agricultural

productivity of the Mekong Delta.

The occurrence of extreme weather events has

increased as well, which can arguably be attributed to the impacts of

climate change. “Since 1901, the number of typhoons and tropical

depressions has risen to 7 or 8 a year. The impact of storms and floods

has intensified in part due to increasing populations and settlements in

vulnerable areas. Though preventive measures have been taken, losses

and damages from disasters are severe and increasing. In the last 10

years alone, natural disasters have cost Vietnam around 800 lives and

1.5% of GDP a year” (ICEM, 5).

Average temperatures in the Mekong Delta have

increased in recent years as well. According to the Institute for

Meteorology, Hydrology and Environment (IMHEN), there has been an

average temperature rise of 0.5 C between the years of 1955 – 2005

across Vietnam, while the city of Can Tho and the DRAGON Institute have

reported an average temperature increase of 0.5 C for Can Tho over the

last 30 years (ICEM, 4).

Saltwater intrusion has increased in the Mekong Delta as well, which can partially be attributed to rising sea levels resulting from climate change. Indeed, “as sea levels rise and storm surges increase, salt water intrusion is a growing risk to agricultural production, hastened by upstream damming and mangrove decline” (Parthemore). According to the 2009 Mekong Delta Climate Change Forum Report, “saline intrusion is reaching further inland and affecting wider areas” of the Mekong Delta, such as in Dai Ngai, where increases of salinity maximums of 8.6% occurred during the period of 1980 – 1989 and increases of 13.1% occurred over the period of 2000 – 2009 (ICEM, 5).

However, the construction of dams further upstream on the Mekong River may also be to blame for the increases in saltwater intrusion. According to a NIC Conference Report from January 2010, “dams on the lower Mekong River prevent renewal of the delta silt deposits and the reduction in flow will allow permanent saltwater intrusion that will kill the mangroves and prevent rice cultivation” (CENTRA Technology, Inc., and Scitor Corporation, 20). Collectively, climate change has already affected the Mekong Delta, and impacts such as increased flooding and saltwater intrusion threaten the agricultural productivity of this critical region.

Projected Future Impacts of Climate Change

According to the 2009 Mekong Delta Climate Change Forum Report, the current climate change trends occurring in the Mekong Delta as described above are projected to not only continue, but to intensify based on various climate and hydrological modeling studies that have been conducted (ICEM, page 6). Vietnam’s average temperature is predicted to increase by between 1.1 C under a low emission scenario to 3.6 C under a high emission scenario above its average temperature during the 1980‐1999 period, while annual rainfall is predicted to increase by 1.0% to 5.2% under the low emission scenario or by 1.8% to 10.1% under the high emission scenario (ICEM, page 6). In addition to increasing amounts of annual rainfall, the timing of the rainfall is predicted to continue to change as well. Rainfall is predicted to “intensify over fewer months in the rainy season . . . while the dry season will become more prolonged” (ICEM, page 6). Shifting rainfall patterns such as this will place an even greater strain on the agricultural production of the Mekong Delta.

Extreme events are predicted to continue to increase in the future, including an increasing number of typhoons with higher wind velocity that extend over longer periods, particularly during El Nin years (ICEM, page 6). The average level of Vietnam’s seas is predicted to rise by 28‐33 cm by 2050 and by 65‐100 cm by 2100 as compared to the 1980‐1999 period (ICEM, page 6). In addition, the annual runoff from the Mekong Basin is predicted to increase as well, with the total annual runoff under one scenario predicted to “increase by 21%, mainly during the wet season and in the upper areas of the Mekong floodplains” (ICEM, page 6).

A key impact of climate change that will impact the

Mekong Delta in the short-term future will result from increased water

flow of the Mekong River due to glacial melt in the Tibetan Plateau,

where its headwaters reside. The maximum and minimum flows of the

Mekong River are expected to shift, such that “over the next century,

the maximum flow of the Mekong is estimated to increase significantly,

while the minimum monthly flows are estimated to decline, meaning

increased flooding risks during wet season and an increased possibility

of water shortage in dry season” (IGSD, 3). The increased flow of the

Mekong River will pose an even greater flooding risk to the Mekong Delta

in the short-term, threatening the agricultural output of this region

and the livelihoods of its residents as a result.

The primary harm site is the Mekong Delta, where the

impacts of climate change threaten the livelihoods of the residents of

this area. However, the predicted decline in the agricultural output of

the Mekong Delta that will result from the impacts climate change would

harm other areas that depend on its agricultural output, including

other parts of Vietnam and other countries in the region. Also, the

areas to which the Mekong Delta refugees migrate may be harmed as well

as a result of increased strain on their levels of resources and the

corresponding conflicts that may potentially ensue.

Due to the global nature of both the causes and impacts of climate change, it is impossible to pinpoint the exact site that is the responsible for the climate change impacts involved with this event, including the glacial melt occurring in the Tibetan Plateau as well as the rising sea levels and increases in rainfall, extreme weather events, average temperatures, and saltwater intrusion experienced by the Mekong Delta. As such, the act site is located internationally.

The potential conflicts associated with the impacts

of climate change on the Mekong Delta could include both civil and

international conflicts. If the migration of Mekong Delta refugees

occurs within the borders of Vietnam, civil conflicts could erupt as

vital infrastructure for delivering water and sanitation services could

be strained and an increased and unsustainable demand for resources may

occur in the areas of Vietnam where the Mekong Delta refugees migrate.

If a cross-border migration of Mekong Delta

refugees to other countries in the region occurs, such as to Cambodia or

Laos, an international conflict could result. An international

conflict may be more likely to occur if refugees cross into Cambodia,

which has historical animosity with Vietnam. As mentioned previously,

an international conflict could also unfold between Vietnam and China if

the perception emerges among the Vietnamese people that Chinese dams on

the Mekong River are to blame for the agricultural issues encountered

by the Mekong Delta. China has also claimed sovereignty in the South

China Sea and is increasingly targeting trawlers fishing in the South

China Sea, which could introduce another avenue to conflict between

Vietnam and China if farmers in the Mekong Delta turn to fishing as

their agricultural output decreases (Parthemore). As such, a shift in

livelihoods from farming to fishing could increase the number of

Vietnamese fishing boats in the South China Sea, which could potentially

result in an international conflict with China.

Currently, a conflict has not yet occurred. However, resource access to critical resources such as food, water, energy, and sanitation services will ultimately be the trigger for the potential conflict between the Mekong Delta refugees and the residents of the areas to which they migrate. Many of the regions to which the Mekong Delta refugees may migrate may already be under environmental stress, such as Cambodia if the lower Mekong and Tonle Sap are negatively impacted by climate change as well (CENTRA Technology, Inc. and Scitor Corporation, 47). As a result, resource access may already be strained, and the influx of Mekong Delta refugees could prove to be the tipping point for conflict.

While fatalities have occurred in the Mekong Delta

due to natural disasters, which can arguably be attributed to the

impacts of climate change, no deaths have yet occurred as a result of a

migration of Mekong Delta residents to other regions.

It is difficult to predict the number of fatalities that may result from such a migration as the number of refugees and the areas to which they may migrate is speculative. It is likely that the higher the number of Mekong Delta refugees, the more potential fatalities may result due to the increased strain the refugees would place on the areas to which they migrate and the corresponding increased potential for conflict that would ensue. Given the high level of uncertainty regarding the number of Mekong Delta refugees and the location(s) they may migrate to, a medium fatality level is assumed due to the large quantity of individuals that may eventually migrate from the Mekong Delta given its high population density.

The causal diagram shown above illustrates the impact that climate change may potentially have on the Mekong Delta in Vietnam in the short-term future. Climate change poses a flooding threat to the Mekong Delta as a result of rising sea levels near low lying land at the mouth of the delta as well as an increased water supply at the Mekong River’s headwaters due to melting glaciers in the Tibetan Plateau. While the Mekong Delta has historically flooded regularly due to annual monsoon rains, increased flooding due to the impacts of climate change would be detrimental to the agricultural productivity and output of the delta, which, as previously stated, is relied upon to feed a large portion of Vietnam as well as numerous other countries in the region. Rising sea levels will increase the salinity of the Mekong River and negatively impact arable land as well.

As a result of the decreased agricultural output

in the Mekong Delta, income per capita in this area will likely fall

given the importance of agriculture to the region. Due to the loss of

livelihoods, an eventual migration of the Mekong Delta’s residents to

neighboring regions of Vietnam and/or neighboring countries could occur.

This would increase the population levels of the regions to which the

Mekong Delta refugees migrate, which could stress vital infrastructure

for delivering water and sanitation services and possibly lead to an

increased and unsustainable demand for ecological resources. If a mass

migration occurred from Can Tho, the biggest city in the Mekong Delta,

this could present a particularly sizeable strain on the resources of

neighboring regions. Ultimately, this poses the potential for social

and/or political unrest as resource shortages may affect the food

security and livelihoods of the neighboring regions.

At the same time, Chinese dams have been built

upstream on the Mekong River to deliver hydropower to fuel China’s

growing energy needs, which reduces the water flow of the Mekong River

to the Mekong Delta. Vietnamese people may perceive that the Chinese

dams are to blame for the decline in the Mekong Delta’s agricultural

output, which increases the potential for an international conflict

between China, Vietnam and other countries impacted by migration and

resource shortages.

As social/political unrest increases, income per capita in the Mekong Delta will likely continue to decline, which will positively reinforce the cycle of migration to other areas and the resulting resource shortages and increased potential for conflict. A positive feedback loop may therefore emerge, threatening the region with escalating levels of conflict.

This conflict is of regional interest as the location

to which the Mekong Delta refugees may migrate is indeterminate and may

involve numerous countries in the region. The strains on resources

resulting from the influx of refugees may therefore impact a number of

states in Southeast Asia.

Also, as stated previously, the agricultural

output of the Mekong Delta is of critical importance to the region and

as such, its decline would negatively impact the food security of

numerous countries. Declining agricultural output in the Mekong Delta

may also result in a greater need for Vietnam to extract resources from

the South China Sea, which could lead to further confrontations with

China over sovereignty of the South China Sea.

This potential conflict may be mitigated through the

implementation of successful adaptation strategies. Already, there are

provinces in the Mekong Delta that are pursuing adaptive agricultural

practices, such as testing and studying cropping patterns and species

suitable to climate change, and modifying infrastructure to prepare for

rising sea levels, such as upgrading and expanding national and

provincial sea-dyke systems and rehabilitating coastal and wetland

forests and mangroves (ICEM, 8). In addition to local efforts,

“international and domestic institutions are focusing on developing new

strains of rice and other plants that can better withstand flooding,

drought and salt water intrusion” (Parthemore).

Existing natural disaster response arrangements between the provinces in the Mekong Delta may prove effective at responding to the impacts of climate change as well, and some provinces have established climate change coordinating structures such as Can Tho, which has a Climate Change Steering Committee in place (ICEM, 8). According to Ky Quang Vinh, a member of the Can Tho Steering Committee for Climate Change,

Research should be carried out on the construction of sea and river dykes, the construction of fresh water reservoirs for the dry season and how to recharge groundwater reservoirs. Planned infrastructural measures for adapting to climate change must address the whole of the Mekong Delta, not Can Tho alone. Awareness and understanding of climate change for local people and government officials is essential. Support from the international community is needed to help Can Tho and the Mekong Delta to find optimal and appropriate measures for adaptation (ICEM, 5).

At a national level, the Vietnamese Government has

adopted the National Target Program in Response to Climate Change (NTP),

which establishes a framework for development planning that accounts

for climate change based on a medium scenario (IPCC B2) for greenhouse

gas emissions (ICEM, 8). At an international level, the Mekong River

Commission (MRC) was established in 1995 to drive cooperation for

sustainable development of the Mekong River, although China and Myanmar

are not members, which hinders its effectiveness at sharing data and

management strategies to sustainably manage the Mekong River (Ardiansyah

and Putri, 18). In April 2010, prime ministers from Vietnam, Cambodia,

Laos People’s Democratic Republic, and Thailand agreed on the substance

of a proposal to help each other in taking action to counter

environmental threats such as climate change, including ecosystem

protection efforts and economic stimulus to the rural poor (Ardiansyah

and Putri, 19).

Collectively, numerous efforts such as these have already been undertaken by both national and local government officials in Vietnam as well as across the international community to support the Mekong Delta in adapting to the growing impacts of climate change. At this point in time, however, whether these efforts can prevent either mass migrations of refugees from the Mekong Delta or corresponding conflicts from occurring is indeterminate.

ICE Cases:

205. BRAHMAPUTRA, India and China Dispute on Brahmaputra River Waters, by Ryan Hodum

218. MEKONG-CHINA, The Drying of the Mekong River, by Nargiza Salidjanova

221. RAJASTAN, The Pattern of Migration in India Due to Climate Change, by Lauren Carroll

229. BANGLADESH, Climate Change Induced Extreme Weather Events & Sea Level Rise in Bangladesh Leading to Migration and Conflict, by William Alex Litchfield

Sources:

Ardiansyah, Fitrian, and Putri, Desak (2011 February). "Risk and Resilience in Three Southeast Asian Cross-Border Areas: The Greater Mekong Subregion, the Heart of Borneo and the Coral Triangle." Retrieved September 11, 2011, from: http://fitrianardiansyah.wordpress.com/2011/02/23/risk-and-resilience-in-three-southeast-asian-cross-border-areas-the-greater-mekong-sub-region-the-heart-of-borneo-and-the-coral-triangle/

CENTRA Technology, Inc., and Scitor Corporation (2010 January). "Southeast Asia: The Impact of Climate Change to 2030 - Geopolitical Implications." Retrieved November 22, 2011, from the National Intelligence Council: http://www.dni.gov/nic/special_climate2030.html

Institute for Governance & Sustainable Development (IGSD) (2010 August). "Retreat of Tibetan Plateau Glaciers Caused by Global Warming Threatens Water Supply and Food Security." Retrieved October 11, 2011 from the Institute for Governance & Sustainable Development: http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CBwQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.igsd.org%2Fdocuments%2FTibetanPlateauGlaciersNote_10August2010.pdf&ei=Y03RTt2kE4fc0QGzsKUW&usg=AFQjCNG9QKdJtT4NQ6B1vX8IHGmnyP1n7g

International Centre for Environmental Management (ICEM) (2009, November 12 – 13). Mekong Delta Climate Change Forum Report Volume I. Retrieved September 11, 2011, from the International Centre for Environmental Management: http://www.icem.com.au/02_contents/06_materials/06-mdcc-page.htm

K k nen, Mira (2008 May). "Mekong Delta at the Crossroads: More Control or Adaptation?" Ambio Volume 37, No. 3: 205-12. Retrieved October 5, 2011 from ProQuest.

Larmer, Brook (2010 April). "The Big Melt." Retrieved September 13, 2011 from National Geographic Magazine: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2010/04/tibetan-plateau/larmer-text

Nguyen, Huu (2007). "Flooding in Mekong River Delta, Vietnam". Retrieved September 27, 2011, from the Human Development Report Office: http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CB0QFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fhdr.undp.org%2Fen%2Freports%2Fglobal%2Fhdr2007-8%2Fpapers%2FNguyen_Huu%2520Ninh.pdf&ei=mUnRTunxE-jj0QGA0MyZBQ&usg=AFQjCNHSW-fz_3yVv36Sr6HgOfkhMrdNrw

Parthemore, Christine (2011, June 6). "Climate Change Adaptation in the Mekong Delta." Retrieved November 22, 2011, from Current Intelligence Magazine: http://www.currentintelligence.net/features/2011/6/6/climate-change-adaptation-in-the-mekong-delta.html

Yun, Joe (2010, September 23). "Challenges to Water and Security in Southeast Asia." Retrieved October 5, 2011, from the U.S. Department of State: http://www.state.gov/p/eap/rls/rm/2010/09/147674.htm

Image Sources:

Mekong River Commission, Technical Support Division, Mekong River Commission Secretariat: http://ffw.mrcmekong.org/floodrisk.htm

Mekong River Commission, Technical Support Division, Mekong River Commission Secretariat:http://ffw.mrcmekong.org/landuse.htm

Mekong River Commission, MRC 2003: Social Atlas LMB. Additional Maps: http://wiki.mekonginfo.org/index.php/121TA_Map_Elevation_LMB

Perry-Casta eda Library Map Collection: Southeast Asia: http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/middle_east_and_asia/southeast_asia_ref_2009.pdf

Wikimedia Commons, image created by NASA: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mekong_delta.jpg

(c)2011 Katie Padilla