I. CASE BACKGROUND

1. Abstract

This case study seeks to discuss the links between climate change and conflict by studying the trials of Newtok, Alaska. Newtok is home to a group of Yu’pik Eskimos and is currently facing high rates of coastal erosion, rising water levels, and melting permafrost as a result of the warming climate. Despite previous efforts to stop the coastal erosion, it has now become necessary for the village to relocate to a more stable and protected location. The impending disappearance of the village has sparked internal political tensions, halting relocation efforts, and laying the groundwork for potential conflict.

2. Description

The Yup’ik Eskimos, once a nomadic people who moved in accordance to their food sources, began to settle into small, permanent villages during the twentieth century. The Yup’ik are a part of a greater native population known as the Qaluyaarmiut, who have lived and hunted along the Bering Sea Coast for over 2000 years (Alaska State Government). The isolation and scarce population of the region has allowed modern day Yup’ik Eskimos continue to practice a subsistence method of life, preserving the hunting and dietary practices established by their ancestors. Their villages remain within the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge, a biologically rich region, which has supplied them with abundant food supply of fish, mammals, and fowl. Historically, the tribes would migrate via dogsled to different seasonal camps, following bird and mammal migrations in order to feed themselves. With the landscape being frozen most of the year, agriculture has not been a viable option for the Yup’ik people. The men have been, and continue to be, responsible for catching the food while the women are in charge of cleaning and preparing the food. Presently, the Yup’ik Eskimos have created permanent villages in which they still subsist mostly from local wildlife and fish, but they also have become more reliant on the infrequent supply deliveries to the villages of fuel, preserved foods, and medicine (Alaska State Government).

The village of Newtok began to be established in 1949 when a group of Yup’ik Eskimos moved from their seasonal winter camp of Old Kealavik to the current village site and began to establish permanent structures at the encouragement of U.S. government authorities who wanted native children to be schooled (Alaska State Government). The first structure erected in Newtok was a school built by the Federal Bureau of Indian Affairs, who was building such schools in many Alaskan Native villages at the time According to some of older villagers, the Bureau of Indian affairs threatened to take custody of the Yup’ik children if the villagers did not adopt a more stationary lifestyle and build a school (York, 2012) . This was the main reason for the move from Old Kealavik, as it was deemed unsuitable for a school by the U.S. Geological Survey. The Newtok site was chosen because it was easily accessible by barge to deliver building materials. The village then developed around the school and had a stable permanent residency by the late 1960s (Alaska State Government).

However, by the 1980s, residences became increasingly concerned by the rate of erosion of the Ninglick River, and in 1983 they received state funding for an erosion assessment to be completed. The Ninglick River Erosion Assessment used historical aerial photographs and site visits do determine the rate of erosion. The report concluded that between June 1957 and May 1983, the north bank eroded at an average of 19 to 88 feet per year—acknowledging that the continued rate of erosion in the future would pose grave challenges for Newtok (Alaska State Government). They estimated that the village had 25-30 years, (approximately 2008-2013) before structural damage would begin to be observed, and recommend village relocation as the most plausible and effective solution (Alaska State Government).

In 1994, the Newtok Traditional Council began evaluating potential relocation sites and petitioning state and federal governments for financial and logistical assistance. The council chose a site nine miles southeast of Newtok, on the north end of Nelson Island and still within the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge. The community of Newtok dubbed the site ‘Mertarvik’, which means “getting water from the spring” in Yup’ik. Reports were prepared by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Newtok Traditional Council worked diligently to create legislation that would allow the Mertarvik land to be transferred into their ownership. With all of the legal hoops to jump through, the process of land transfer took from 1996 to 2003 until U.S. Public Law 108-129 was enacted, permitting the land exchange (Alaska State Government). Every year the river bank retreated closer and closer to the village, but relocation seemed to be quickly forthcoming as much progress was made.

While the village struggled to make the relocation a legal reality, they were continually faced with additional challenges. One of the most dramatic turn of events occurred in 1996, when a particularly strong storm stripped away a land buffer that had previously separated the Newtok River from the Ninglick River. With that barrier gone, the Ninglick River overtook the smaller Newtok River, creating a slough and increasing the susceptibility of Newtok to flooding. This damage was devastating to the village as the Newtok River had been essential to barge deliveries of fuel and resources, and had been their means of disposing of their sewage. The stronger flow of the Ninglick River forcing the waste back towards the village has contributed to health and sanitary issues.

Flood September 22, 2005; photo taken by Stanley Tom http://commerce.alaska.gov/dnn/dcra/PlanningLandManagement/NewtokPlanningGroup/NewtokVillageRelocationHistory/NewtokHistoryPartThree.aspx

Despite these setbacks, the village continued to move forward with their relocation plans. However, another storm in 2005 completely destroyed Newtok’s barge landing, robbing the village of any cost-effective way to receive deliveries of construction materials for the relocation. The altered hydrology of the Newtok River by the Ninglick River continues to make barge deliveries extremely difficult, so they can only be made at certain times and under certain conditions. This restriction of resources has been detrimental to the standard of living for the community and has delayed construction progress at the new village site.

Due to the floods Newtok faced in 2004 and again in 2005, the village was included in two federal disaster declarations: DR-1571-AK (2004 Bering Sea Storm) and DR-1618-AK (2005 Fall Sea Storm) (Alaska State Government). Suzanne Goldenberg (2013), the U.S. Environment Correspondent for The Guardian, has dubbed the villagers of Newtok as ‘America’s first climate refugees’. And truly, Newtok has faced unprecedented challenges for a village in the United States. Many government policies are now being questioned and re-evaluated in light of Newtok’s challenges. For example, before this crisis, no state or federal agency had the authorization ability to relocate an entire village. Additionally, many agencies have population thresholds in order for investments to be made— Newtok as a community of approximately 350 people do not qualify for most investments. The current estimates of relocating the village amount to $130 million (Goldenberg, 2013).

Location of former barge landing destroyed by erosion; photo: Jon Menough, DEC VSW

http://commerce.alaska.gov/dnn/dcra/PlanningLandManagement/NewtokPlanningGroup/NewtokVillageRelocationHistory/NewtokHistoryPartThree.aspxThe Newtok Planning Group was formed in 2006 to be a facilitating tool between multiple local, state, and federal groups. Initially the Newtok Planning Group made great strides in organizing and initiating progress—planning and designing the village at Mertarvik, and beginning construction at the new site. In the six-year period between 2006 and 2012 construction continued; completing three homes, a barge landing, and laying the groundwork for an evacuation site (Alaska State Government). As there are currently 63 existing homes in Newtok, much work is still needed. Construction has been a slow-moving process as builders have to wait for the warmer seasons to continue work.

The most recent obstacle for the relocation of Newtok has arisen from a dispute within the Newtok Traditional Council which has halted all progress in relocating the community. In August of 2013, community members attempted to throw Stanley Tom, the tribal council administrator who has overseen the relocation process for the past seven-years, out of office (Goldenberg, 2013). In his position, Mr. Tom is the equivalent of a mayor in Newtok. Extreme dissatisfaction has been expressed over his handling of the move to Mertarvik and his neglectful treatment of the existing village at Newtok. This dissatisfaction may, however, stem from the growing fear of the community that the relocation will not be completed in time. They may simply be looking for someone to blame.

Several attempted elections have been pursued to elect new members to the council, but the existing council has refused to acknowledge the results and Mr. Tom refuses to step down stating that he knows what is best for the village. In all interviews, Mr. Tom portrays himself as a man working against all odds to save his village and way of life. According to Mr. Tom, he has been working diligently to enlist the aid of the U.S. government, but he has hinted at the racism of those he is asking for help. In an interview with Anna York of University of North Carolina, Mr. Tom is quoted saying, “They don’t know how to do it [in reference to relocating the village]. They don’t know how to listen to me probably because I’m native, and they’re probably saying I don’t know nothing,” (York, 2012).

Whether or not Stanley Tom is the villain in this story, the standoff between council members and villagers has halted any potential state and federal funding for the relocation efforts due to confusion over who holds legal signing authority. This halting of funds and further delay of relocation may prove to be devastating to the village. With every passing day, the Ninglick River encroaches more on the village, and as the threat looms nearer, tensions are rising increasingly.

It has now been a full decade since the land exchange was signed into law, and the village of Newtok has yet to be relocated as a result of the numerous aforementioned obstacles. The security and quality of life in Newtok is in a steady decline, but due to the relocation plans and the imminent threats of coastal erosion, the village does not qualify for funding to improve existing structures such as a new barge landing, fuel tanks, or sewer facility (Alaska State Government). Recent reports predict that the highest point in Newtok will be underwater by 2017, and that estimate becomes more of a reality with every passing day (Alaska State Government; Goldenberg, 2013). The community of Newtok remains trapped, with infrastructure crumbling around them, and no place to flee to. Times are getting increasingly desperate, creating the potential for serious, and possibly deadly, conflict to arise.

Video Source: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l8F_r2Oyl8I The video above gives an overview of the challenges facing the community of Newtok, Alaska and how they relate to issues of climate change worldwide.

3. Duration

The coastal erosion and rising water levels have been occurring for decades, however, complications arose starting in the 1990’s. The conflict is ongoing, and is likely to increase in intensity within the decade if not resolved. The image below depicts the severity of erosion between 1983 to 1996.

Newtok Background for Relocation Report, ASCG; http://commerce.alaska.gov/dnn/dcra/PlanningLandManagement/NewtokPlanningGroup/NewtokVillageRelocationHistory/NewtokHistoryPartTwo.aspx

4. Location

Coordinates: 60.9444° N, 164.6442° W

Continent: North America/Polar

Region: North West/Arctic

Country: United States → Alaska → Newtok.Newtok is a village located north of Nelson Island in Alaska, near the Bering Sea. It is located on the Ninglick River and is within the boundaries of the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge.

5. Actors

The main actors participating in the conflict are the villagers of Newtok and the Newtok Traditional Council. United States’ state and federal agencies are peripheral actors in this conflict.

II. Environment Aspects

6. Type of Environmental Problem

The main environmental problem in Newtok is Climate Change which has contributed to increased coastal erosion, rising water levels, more intense storms, and thawing permafrost.

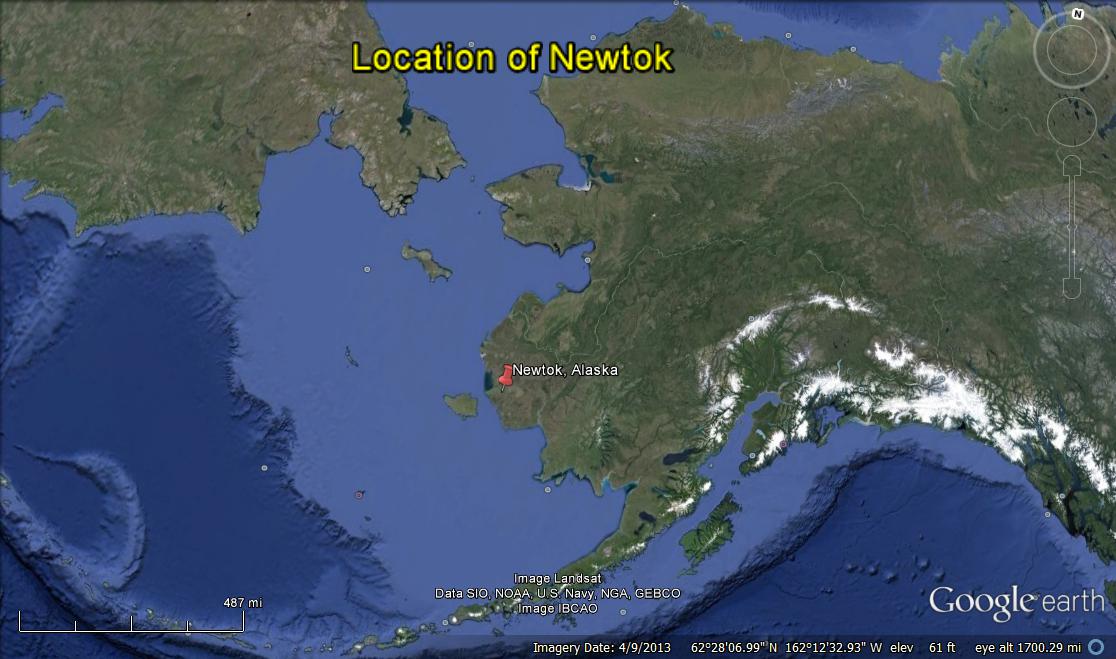

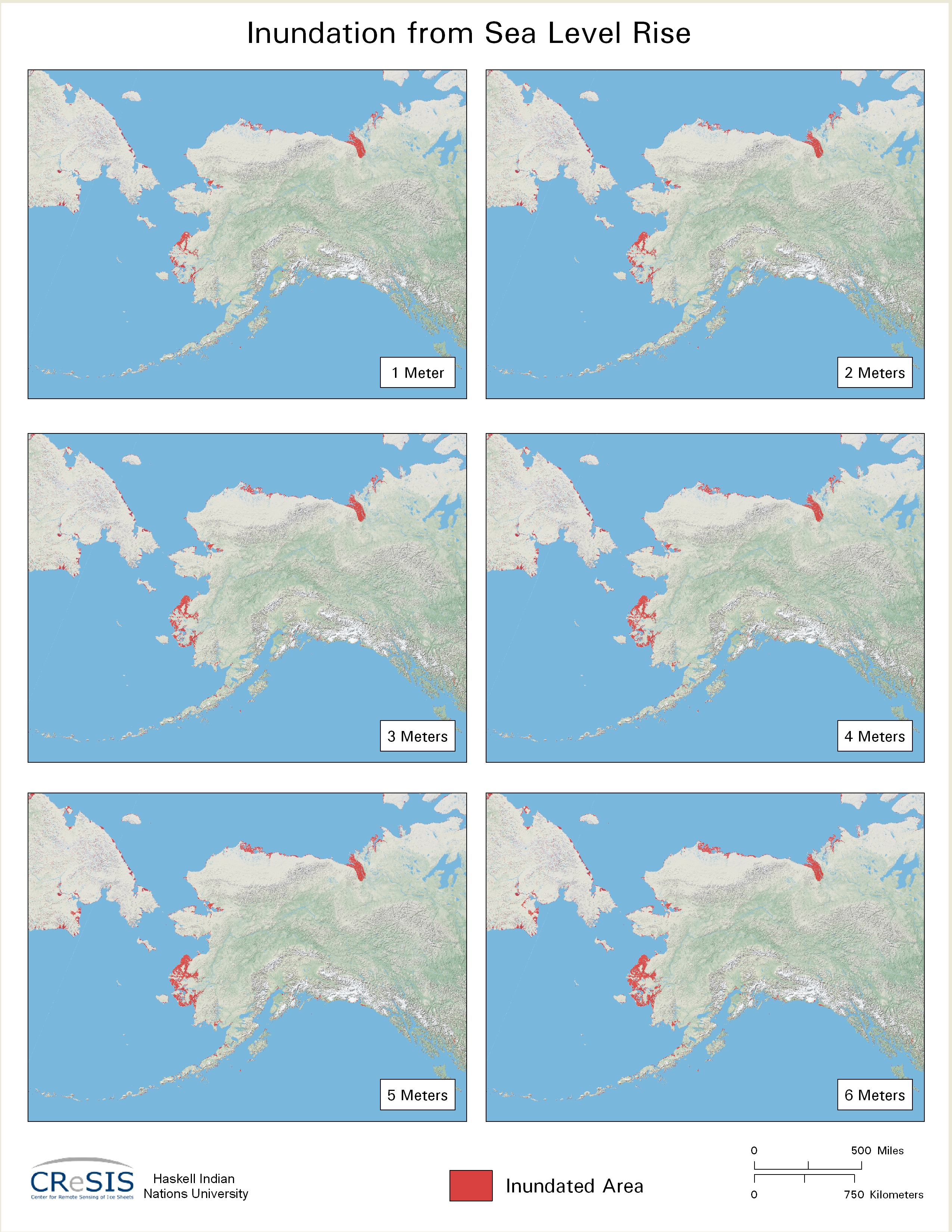

Below are two maps. The first (Figure 1), depicts the location of Newtok in Alaska, while the second (Figure 2) is a series of images which illustrate the areas in Alaska most threatened by inundation of sea-level rise at different increments of rising. When comparing the two images, it is quite clear that Newtok falls within the region most at risk.

Figure 1: Location Map courtesy of Google Earth & Erin Emory

Figure 2: Alaska Sea-Level via Haskell Indian Nations University: https://www.cresis.ku.edu/data/sea-level-rise-maps

The video below presents the faces of Newtok’s climate refugees through a series of images and interviews. Included in this video are clips of Stanley Tom, the controversial tribal council administrator.

Video Source: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u7i9LBeZ1UU

7. Type of Habitat

Cool/Polar

8. Act and Harm Sites:

(a) Newtok, Alaska

(b) Climate Change is an issue which is exacerbated globally by destructive human behaviors. Therefore it is difficult to determine any specific site that is contributing more to the issue in Newtok than others.III. Conflict Aspects

9. Type of Conflict

The immediate conflict in Newtok is civil and very regionally based, however, it has the potential to become international in future decades with migrants/climate refugees making their way northward as well as further inland.

10. Level of Conflict

Several categories factor into the conflict including natural environmental changes, political disputes, and crumbling infrastructure.

11. Fatality Level of Dispute (military and civilian fatalities)

The fatality level of dispute is currently low with 0 reported conflict-related fatalities. However, there have been health concerns due to infrastructure deterioration which contributed to 29% of infants from 1994-2004 being hospitalized for lower respiratory tract infections. In upcoming years, the conflict intensity will remain low, but conflict related fatalities may be more likely if the dispute is not resolved (Alaska State Government).

IV. Environment and Conflict Overlap

12. Environment-Conflict Link and Dynamics:

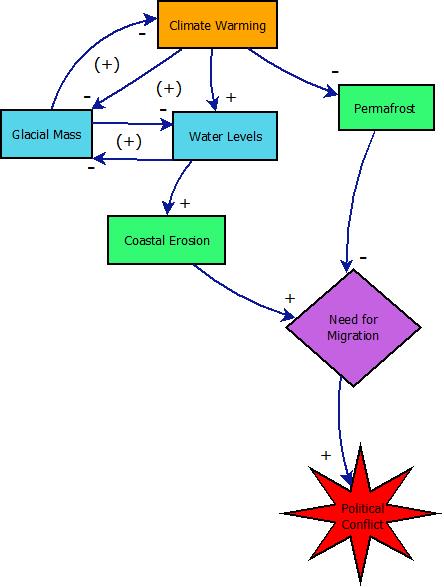

Figure 3 illustrates the main drivers of the conflict in Newtok. As the climate gets warmer, bodies of water such as oceans and rivers absorb the heat and expand causing overall water levels to rise (Jenkins, 2013). This shows a positive relationship between the variables of climate warming and water levels, because as one increases, the other increases as well. An increase in water levels is also seen as a result in a loss of glacial mass. As glaciers melt, water is added into bodies of water, causing them to rise. In the past, energy from the sun has been reflected off of glaciers. With the decrease in glacial mass, less sun energy is being reflected and more sun energy is being absorbed into the oceans, creating a reinforcing feedback loop in which less glacial mass increases water levels which in turn contributes to decreasing glacial mass even more (Jenkins, 2013). Additionally, glaciers reflecting less sun energy and bodies of water absorbing more energy contribute to greater climate warming as heat that would have been reflected back out of the atmosphere is instead absorbed. The closed loop of these three variables creates a reinforcing relationship in which greater climate warming contributes to higher water levels which leads decreasing glacial mass which contributes to greater climate warming. Climate warming also contributes to melting permafrost, which in the case of Newtok has turned the once stable ground into a boggy marsh, causing structures to deteriorate and sink.

The reinforcing feedback loops observed on the left-hand side of Figure 3 and the melting permafrost feed the rest of the relationships in the diagram. Rising water levels contribute to greater coastal erosion, which presents a dilemma for the people of Newtok. Water levels and coastal erosion are increasing at such a rate that their village is projected to be under water by 2017(Goldenberg, 2013; Alaska State Government). As mentioned in earlier sections, increased coastal erosion and deteriorating infrastructure make the need for the people of Newtok to migrate more pressing. The increasing need to migrate and the lack of resolution then put pressure on the local political system, which is in charge of relocating the village and preserving tribal culture.

As the issue currently stands, relocation efforts are at a standstill due to aforementioned disputes in village leadership. The longer that it takes to resolve the issue and relocate the village, the more likely it becomes for conflict to break out. Although conflict has not yet turned violent, if it were to develop to that level, a new feedback loop might be observed. Greater conflict may increase the need to migrate in order to avoid the altercation, while the pressing need for village relocation continues to fuel the political conflict.

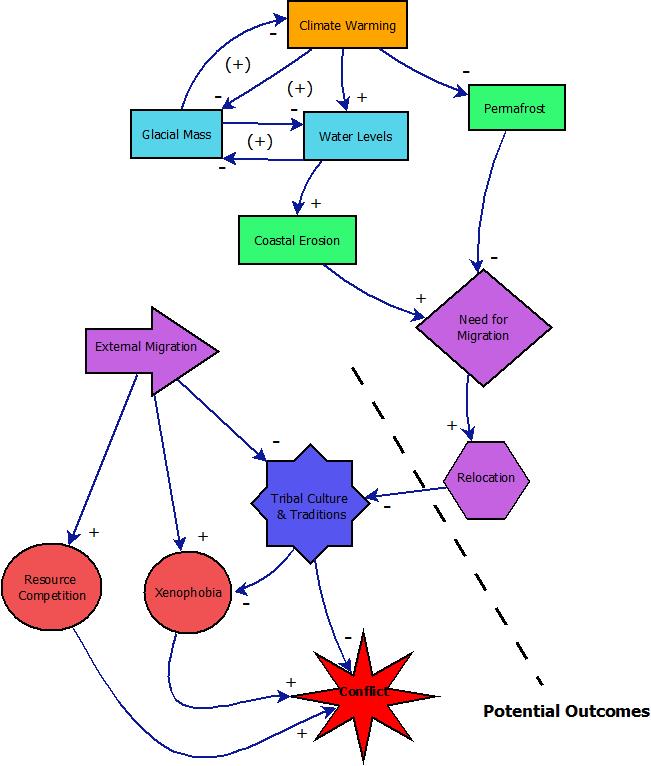

Figure 4 expands on Figure 3 illustrating how conflict continues to be a possibility in the future even if village relocation occurs. The relocation of the Newtok community poses potential threats to tribal culture and traditions as a large-scale move might fragment, transform, or make them obsolete. Additionally, it is projected that upcoming decades will bring large-scale migrations northward which may bring a large influx of foreigners into the previously isolated region traditionally inhabited by Yup’ik Eskimos. The interactions with other cultures also pose a threat to tribal culture and traditions. The villagers of Newtok may see the influx of migrants as a threat to local resources given their subsistence nature, and they may experience xenophobia. All of these factors have the potential to feed into a new, potentially violent, conflict.

Video Source: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ayUweevtzc

Video Above: Nathan Tom and his wife speak with Suzanne Goldberg of the Guardian about the fears they face living at the outermost edge of Newtok. They provide their perspective on the implications climate change may have on tribal life and traditions.

13. Level of Strategic Interest

The Newtok conflict falls into State & Substate (native council) levels of interest; however the same concerns stretch regionally as nearly two hundred other native villages face the same issues.

Figure 5, depicts the other Alaskan villages that currently affected by flooding and erosion. The US GAO reports that 184 of 213 native villages in Alaska are facing these issues presently—that’s over 86% of the villages (GAO qtd in Huntington, Goodstein et al. 2012)! Clearly, Newtok is just the beginning of a much larger and more serious issue. In the coming decades, the United States may experience many more climate refugees within its own borders.

14. Outcome of Dispute:

Dispute still in progress.

15. Implications for the Future

184 out of 213 native villages in Alaska currently face flooding and erosion and are predicted to need relocation similarly to Newtok (GAO qtd in Huntington, Goodstein et al. 2012). Since Newtok is at the forefront of this potentially massive climate-driven crisis, the details and outcome of their case may ultimately set the precedent for how the U.S. handles all climate refugee cases in the future.

V. Related Information and Sources

16. Related ICE and TED Case

The cases listed below may be used for further reference as they also highlight the relationships coastal erosion, water-level rise, and climate migration have with conflict in other parts of the world. The cases The Maldives, Tuvalu, Bangladesh, Palau, Kiribati, and the Solomon Islands provide additional instances of rising-water levels and coastal erosion leading to the displacement of communities. The Sami case illustrates how climate change can be detrimental to the traditional lifestyles and customs of indigenous peoples.

- 206. The Maldives

- 210. Tuvalu

- 229. Bangladesh

- 242. Palau

- 243. Sami & Arctic Warming

- 244. Kiribati

- 250. The Solomon Islands

- 283. The Maldives (part II)

17. Relevant Websites and Literature

- Alaska State Government. Division of Community & Regional Affairs. Newtok Planning Group.

Web. <http://www.commerce.state.ak.us/dcra/planning/npg/Newtok_Planning_ Group.htm>.

- Goldenberg, Suzanne. “America’s First Climate Refugees.” The Guardian. 2013. Web.

<http://www.theguardian.com/environment/interactive/2013/may/13/newtok-alaska

climate-change-refugees>

- Goldenberg, Suzanne. "Relocation of Alaska's sinking Newtok village halted." Guardian. 5 Aug

2013: n. page. Web. 12 Sep. 2013. <http://www.theguardian.com/ environment/2013/aug/05/alaska-newtok-climate-change>.

- Heffernan, Olive. "Adapting to a Warmer World: No going back." Nature. 491.7426 (2012):

659-661. Web. 12 Sep. 2013.

- Huntington, Henry P., Eban Goodstein, et al. "Towards a Tipping Point in Responding to

Change: Rising Costs, Fewer Options for Arctic and Global Societies." Ambio. 41.1 (2012): 66-74. Web. 12 Sep. 2013.

- Jenkins, Amber, ed. "Global Climate Change." National Aeronautics & Space Administration. Web. 1 Oct 2013 <http://climate.nasa.gov/causes>.

- Larsen, Peter H., et al. "Estimating Future Costs for Alaska Public Infrastructure at Risk from

Climate Change." Global Environmental Change. 18.3 (2008): 442–457. Web. 12 Sep. 2013.

- Lee, James R. Climate Change and Armed Conflict. New York, NY: Routledge, 2009. Print.

- NPR Staff, “Impossible Choice Faces America’s First Climate Refugees.” All Things Considered. NPR. May 2013. Web. <http://www.npr.org/2013/05/18/185068648/

impossible-choice-faces-americas-first-climate-refugees>

- Richardson, Joan. "On the Edge, In the Center." Phi Delta Kappa International. 92.6 (2011): 4.

Web. 12 Sep. 2013.

- United States. Environmental Protection Agency. Future Climate Change. 2013. Web.

<http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/science/future.html>

- York, Anna. “Alaskan Village Stands on Leading Edge of Climate Change.” Powering A Nation.

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2012. Web.<http://unc.news21.com/ index.php/stories/alaska.html>.

[Erin Emory© December 2013]