I. CASE BACKGROUND

1. Abstract

The San Juan River,

as it flows in Central America, demarcates a border between Nicaragua

and Costa Rica. This border has been a source of contention between the

two states for years. The situation around the border issue is already

tense for both governments as an issue of national pride. Armed forces

have been mobilized on both sides of the border in recent years yet have

avoided armed conflict, redirecting new attention to an old dispute.

Added stresses caused by climate change, such as exteme droughts which

could cause water scarcity in the San Juan River Basin, only exacerbate

the problem. With such competition for available water resources, these

two governments may decide that armed conflict is worth the risk.

|

------- San Juan River

|

2. Description

This case study

looks at the border dispute between Nicaragua and Costa Rica over the

San Juan River. The San Juan River acts as the eastern border between

southern Nicaragua and northern Costa Rica. This border is demarcated by

the path of the San Juan River east of Lake Nicaragua. Despite the fact

that these two neighboring states have typically been friendly, this

border has not always been a source of such amiable relations. Both

Nicaragua and Costa Rica claim rights to the San Juan River, and though

they do not claim equal rights, they have never been able to fully

agree. Costa Rica claims more rights to the San Juan than Nicaragua is

willing to grant based on the 1858 Canas-Jerez treaty. This treaty made

the San Juan River the permanent border between both states. The main

tenants of the treaty stated the following: Nicaragua would "have

exclusive dominion and the highest sovereignty over the water of the San

Juan", Costa Rica would be given "perpetual rights of free navigation"

on the San Juan "for the purpose of commerce", and Nicaragua could not

enter into unilateral negotiations concerning a canal project without

consulting Costa Rica beforehand. Clearly the Canas-Jerez treaty set the

stage for opposing interpretations of rights to the San Juan River.

Nicaragua believes that it is the rightful owner of the San Juan as laid

out in the treaty yet Costa Rica also believes that it has rights to

the same water. Based upon the ambiguity of the treaty and the

disagreement between both governments, the Untied States was brought in

to arbitrate in 1888. As a result, the Canas-Jerez treaty was reaffirmed

in the Cleveland award but specified that Costa Rica's right to

navigation was onlyfor ships with cargo consisting of commercial

merchandise and did not include carrying arms. The Cleveland award did

clear up some of the ambiguity of the Canas-Jerez treaty, but did not

even begin to bring Nicaragua and Costa Rica to the same table regarding

interpretations of river rights alltogether.

Over the next 100

years or so, the San Juan River would remain a point of discontent

between both governments. In the late 19th and early 20th century, Costa

Rica would refuse to concede to canal projects which brought resentment

from the Nicaraguan government which desperately wanted a canal through

the San Juan route. Then in the 1940's Costa Rica undertook the

unilateral dredging of the Colorado River, a tributary of the San Juan

River which runs through Costa Rica. This dredging completely changed

the flow of water at the fork of the San Juan and the Colorado. Before

this decision to dredge in the Colorado, the majority of the water at

the fork of these two rivers would continue to flow to the north along

the route of the San Juan River. Today, after the dredging process, the

fork between the two rivers has shifted to widen at the mouth of the

Colorado, thus diverting more water into this tributary of the San Juan

as opposed to its natural course continuing down the San Juan River

itself. This water is now directed into Costa Rican territory and has

caused the last 37 kilometers of the San Juan River in Nicaragua to

become virtually unnavigable as it dries out and clogs with silt and

other sediment. This drying of the San Juan River has caused it to shift

northward further and further into Nicaraguan territory. Since the

officially demarcated border is the flow of the San Juan River,

Nicaragua is not only losing a valuable water resource, but is also

effectively losing territory to Costa Rica as an effect of its

unilateral dredging.

|

The fork of the San Juan River and the Colorado River in the 19th century, pre-dredge.

Water is flowing on its natural course down the San Juan River. |

|

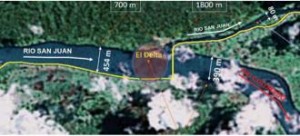

The fork of the San Juan River and the Colorado River in the 20th century, post-dredge.

Water is being diverted from the natural flow of the San Juan River into the Colorado River. |

Beginning in 2010,

Nicaragua set on its own path to dredge the San Juan River in order to

restore the flow of water back to its original course and regain its

water and its land. The Costa Rican government has openly opposed the

dredging, which is conveniently ignoring the fact that they did

essentially the same thing 60 years prior. Costa Rica claims that it has

concerns about the potential environmental impacts of the dredging,

especially since a large portion of the Colorado River runs through

Barra del Colorado national wildlife refuge. They claim that the

wildlife here, which has now become accustomed to and dependent on the

increased waterflow would be adversely affected. The Nicaraguan dredging

project, known as the Sovereignty, was temporarily halted due to

political pressures but has since been restarted and gained Nicaraguan

military backing. In October 2010, this dredging project nearly brought

the border dispute to blows in armed conflict. Nicaraguan troops were

seen, via aerial photographs, to be occupying Isla Calero as a part of

the dredging project which is considered to be Costa Rican national

territory.

In

response, Costa Rica sent in its police force, La Fuerza Publica, to the

town of Barra del Colorado in the northeastern corner of Costa Rica,

which is the closest town to Isla Calero. Costa Rica lacks an official

army and often cites this fact as a reason to use diplomatic means in

solving its disputes and often portrays itself as a non-aggressor or

victim. However, the Costa Rican government has a budget of

approximately $240 million for the armed police force that it does have,

which is almost five times more money than the Nicaraguan government

budgets for its army. In fact, if one did not know that Costa Rica had

no army, it might mistake the police force, pictured to the left, for

military personnel. These well trained and well equipped "police

officers" almost clashed with the Nicaraguan army but luckily the

Nicaraguans pulled their own men from Isla Calero before this became a

reality.

The

degree of involvement of the armed forces in this narrative may seem

excessive. But this is a direct result of the nationalism that surrounds

such border disputes. Both Nicaragua and Costa Rica have had much

political instability. In Nicaragua, one of the poorest countries in the

America's, almost half of the population lives below the povery line.

Its history since independence has been plagued with corruption, US

interference, and military dictatorships. Costa Rica has been a poor

state since its colonial days and about 30% of its population lives

below the poverty line. Additionally, its coffee economy has stratified

society and marginalized much of the population. Due to these, and

several other factors, governments in both states must constantly work

to maintain their legitimacy. Making the border dispute a nationalist

issue helps each government maintain its legitimacy by working to gain

more water or land for its people. Without the unstable political

climates, these two governments would have no reason to nationalize

their border disagreement. But instead, it becomes an issue of national

pride and compromise is simply not a viable option.

A

second issue of contention, not related to navigational rights of the

San Juan, between Costa Rica and Nicaragua regarding their border is

illegal immigration. This immigration mostly takes place from southern

Nicaragua into northern Costa

|

Nicaraguan immigrants arriving in Costa Rica |

Rica

via the San Juan River border. This immigration takes place for several

reasons but mostly is due to the political instability of Nicaragua and

the ease of illegal immigration into Costa Rica. This process is easy

for Nicaraguans because Costa Rica simply lacks the resources to control

the flow of people across the border. Since the 1970s, there has been a

nearly constant flow of illegal Nicaraguan immigrants which has become a

source of hostility from Costa Ricans towards Nicaraguans in the

region. Much of this xenophobic hostility stems from the widespread

stereotypes of Nicaraguans as violent and crime ridden. It also stems

from the increase in job competition that Nicaraguans bring to northern

Costa Rica. In the 1990's, public opinion in Costa Rica showed that 56%

of Costa Ricans opposed the presence of Nicaraguans in their country.

Again, the problem of illegal immigration is framed in nationalist terms

to grant legitimacy to the Costa Rican government and to provide

popular support for the regime. This creates an "us vs. them" mindset

between Costa Ricans and Nicaraguans which exacerbates border tension.

In addition to the

potential reasons for conflict stated above, it is predicted that some

of the most serious effects of climate change will be felt in Central

America and thus in this border region. Not only will extreme climatic

changes be felt here, but they will be felt very soon. Given the already

tense nature of the San Juan region and its role as an international

border, the coming effects of climate change such as drought, flooding,

and resource competition, will only exacerbate these tensions. It could

be the very spark needed to take this hostile political climate and set

it on fire.

3. Duration

Duration: Ongoing

The dispute between

Nicaragua and Costa Rica over the San Juan River began back in 1821

when they were both granted independence from Spain. Costa Rica annexed

two regions of Nicaragua, Nicoya and Guanacaste, shortly after

independence which changed the existing border. Finally in 1858 the

Canas-Jerez Treaty initiated a legal disagreement between the states.

The disagreement began over Costa Rica's rights to navigate the San

Juan, and has escalated to defining the actual location of the San Juan

River and potentially the resulting international border. This dispute

has extended into the 21st century where it came close to armed conflict

as recently as 2010, which classifies it as ongoing.

4. Location

The main location

of this dispute is the eastern portion of the border between Nicaragua

and Costa Rica to the east of Lake Nicaragua. This includes land regions

in Nicaragua from San Carlos in the West to San Juan Del Norte in the

East. And land regions in Costa Rica from Los Chiles to Colorado. The

chance of a conflict erupting that would involve the entirety of either

state is unlikely and thus the location is restricted to the border

region.

5. Actors

The actors involved in this dispute are:

- The inhabitants of the border region, both Costa Ricans and Nicaraguans

- The Costa Rican Government

- The Nicaraguan Government

Back To Top

II. ENVIRONMENTAL ASPECTS

6. Type of Environmental Problem

The basic

environmental problem is rapid climate change. Central America is

expected to have dramatic effects from the current rate of climate

change. Such effects include sea level rise, salinisation, extreme

drought, and extreme flooding. Unfortunately the predictions and

forecasting of such events is not much more specific. Different regions

may experience severe droughts while others suffer from intense flooding

but which effects will be felt in which region is not known. Despite

this uncertainty, the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has

forecasted changes in both precipitation and temperature in this region

to the best of its ability. According to the IPCC's Fourth Assessment

Report relesed in 2007, Central America is supposed to experience

increases in temperature between 1 degree Celsius and 6.6 degrees

Celsius by the year 2080, depending on the season. Precipitation changes

by the year 2080 are predicted to be anywhere between a 30% decrease

and an 8% increase.

Change in Temperature (Cels.) |

|

2020 |

2050 |

2080 |

| Central America |

Dry Season |

+0.4 to +1.1 |

+1.0 to +3.0 |

+1.0 to +5.0 |

| |

Wet Season |

+0.5 to +1.7 |

+1.0 to +4.0 |

+1.3 to +6.6 |

Change in Precipitation (%) |

|

2020 |

2050 |

2080 |

| Central America |

Dry Season |

- 7 to + 7 |

- 12 to + 5 |

- 20 to + 8 |

| |

Wet Season |

- 10 to + 4 |

- 15 to + 3 |

- 30 to + 5 |

These forecasts by

the IPCC, which is considered the premiere climate change organization

today, illustrate the uncertainty surrounding climate change and its

effects in Central America. The temperature in Costa Rica and Nicaragua

will increase, it is only the scale of this increase that is not

certain. On the other hand, the San Juan River and its basin could be

receiving 30% less precipitation than it did in 2007 or as much as 8%

more. Yet since the temperature will obviously be increasing and the

forecast seems to favor decreased precipitation, the remainder of this

analysis will assume drought to be the most important obstacle in the

San Juan border region.

7. Type of Habitat

The habitat of both

Nicaragua and Costa Rica, as well as their shared border region, is

tropical. It has a wet season and a dry season like most tropical

habitats. Most of the land area around the border however, is

specifically forest. These forests feed off of the San Juan River and

drought could be potentially devastating.

8. Act and Harm Sites:

The act and harm

sites will be the San Juan River basin and civilian populations affected

by the severe droughts. These climate change induced environmental

changes will reduce the water supply to both Costa Rican and Nicaraguan

populations who rely on the San Juan River Basin. Populations in this

area will experience water scarcity and increased competition for

remaining water resources.

Back To Top

III. CONFLICT ASPECTS

9. Type of Conflict

Despite that fact

that this region is located in a potential "Hot War" zone regarding the

predicted effects of climate change, the conflict between Nicaragua and

Costa Rica over the San Juan River and resulting border has been kept

mostly in the political realm. The governments of each state have made

conflicting claims, condemned one anothers actions, and even sought

third party arbitration. This began with the United States and the

Cleveland award in 1881, as previously noted. However this political

conflict has manifested in third party arbitration much more recently as

well. In 2005, Costa Rica decided to give into the Nicaraguan

government by seeking a ruling at the International Court in The Hague.

The International Court's decision ,

10. Level of Conflict

Currently, the conflict remains dormant. No physical violence or clash of armed forces is occuring. But Central America,

and hence both Nicaragua and Costa Rica, is located in a potential "Hot

War" zone due to the predicted effects of climate change. This makes

the region more prone to potential conflict and very important to watch

in the future.

11. Fatality Level of Dispute (Military and Civilian fatalities)

No fatalities have

been reported due to the border dispute. While military personnel have

had been deployed, armed conflict has been avoided for at least the past

100 years. The majority of this dispute is non-violent.

Back To Top

IV. ENVIRONMENT AND CONFLICT OVERLAP

12. Environment-Conflict Link and Dynamics:

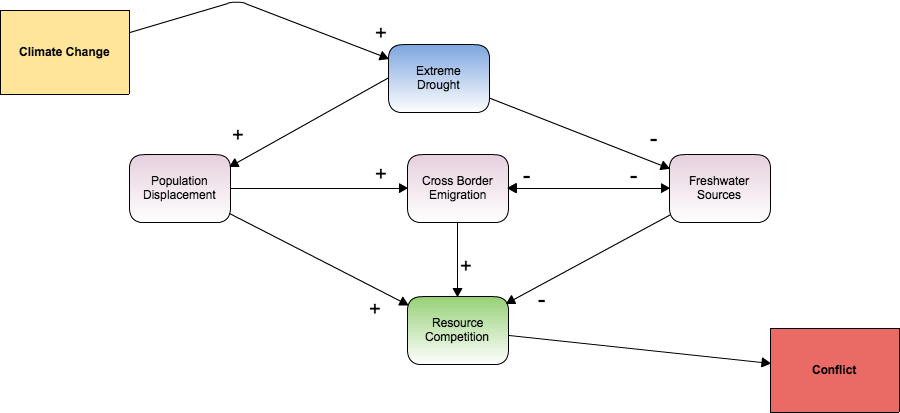

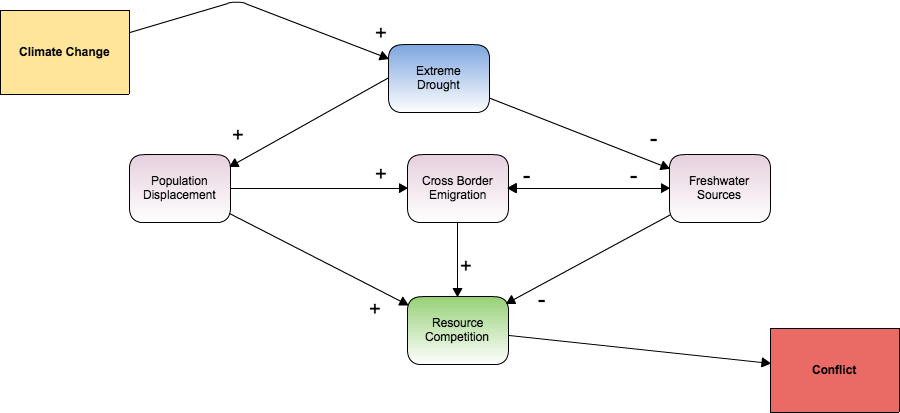

This causal loop

diagram shows the links between climate change and potential conflict

around the Nicaragua/Costa Rica border. Climate change in this region is

predicted to reduce precipitation, while also increasing temperatures.

Increased climate change, will cause increased cases of extreme drought.

This drought will in turn have two effects: to cause more population

displacement for people who can no longer live off of the land, and to

cause a reduction in freshwater resources. Both a loss of water source

and the population movement already in place will cause more Nicaraguans

to emigrate to Costa Rica since most of the San Juan is diverted into

Costa Rican territory. This movement of peoples could be legal but will

most likely be illegal given established patterns of immigration across

the border. Adding more people to the northern region of Costa Rica will

increase resource competition between already hostil groups. The Costa

Rican government could plausibly to crack down on Nicaraguan illegals to

the likely dismay of the Nicaraguan government. With national pride in

the way, and a valuable water resource at stake, conflict is likely to

erupt.

13. Level of Strategic Influence

In order to avoid

this outcome, the actions should come from the inter-governmental level.

The governments of both Nicaragua and Costa Rica need to stop defining

this border dispute in nationalist terms and instead work on

collaborative projects to protect the San Juan River and its basin from

climate change. The populations of each state would need to accept this

cooperation and also understand that their xenophobic tendencies only

make the problem worse. A

bilateral agreement and/or project, with the support of Nicaraguan and

Costa Rican citizens, to put aside differences and protect a valuable

resource could mitigate the chance of nationalist conflict.

Back To Top

V. RELATED INFORMATION AND SOURCES

15. Related ICE Cases

ICE Case 5 Peruecwar

ICE Case 32 Soccer

ICE Case 236 Aymara

16. Relevant Websites and Literature

- "San Juan River -- Border dispute between Costa Rica and Nicaragua"

http://www.geog.umd.edu/academic/undergrad/harper/Berrios.pdf

- "The Nicaragua-Costa Rica Border Dispute - A Symptom of 'Tico' Decline?

http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/ideas/2011/03/the-nicaragua-costa-rica-border-dispute-‚€“-a-symptom-of-‚€˜tico‚€™-decline/

- "The Rio San Juan: Source of Conflicts and Nationalism"

http://www.envio.org.ni/articulo/3112

- "Nicaragua's President Accuses Costa Rica of Trying to Steal Rio San Juan"

http://www.ticotimes.net/Current-Edition/News-Briefs/Nicaragua-s-President-Accuses-Costa-Rica-of-Trying-to-Steal-Rio-San-Juan_Tuesday-November-02-2010/(offset)/10

- "The Truths that Costa Rica Hides"

http://www.el19digital.com/documentos/TruthsCostaRicaHides_webVersion.pdf

- "Experience Nicaragua - History"

http://library.thinkquest.org/17749/history.html

- "The Political Formula of Costa Rica"

http://lanic.utexas.edu/project/etext/llilas/tpla/8801.pdf

- "Climate Change 2007: Working Group II: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability"

http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg2/en/ch13.html

- "Climate Change and the World's River Basins: Anticipating Management Options"

http://www.jstor.org.proxyau.wrlc.org/stable/20440816?

Back To Top