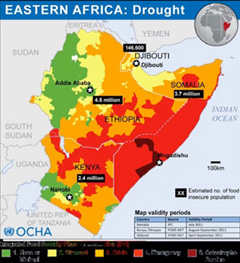

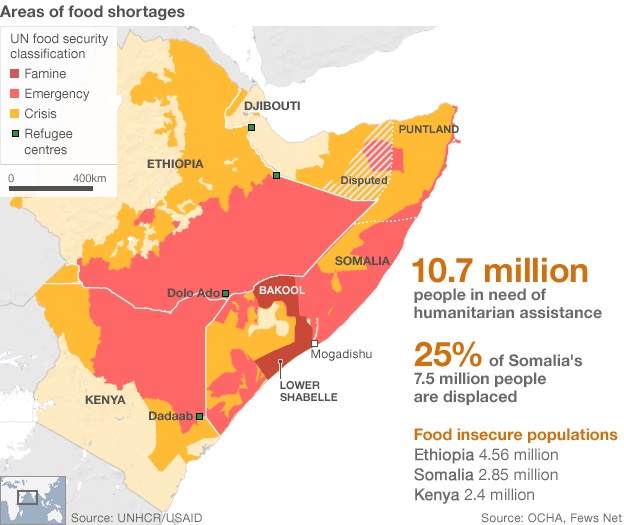

Abstract: This project will critically consider the intricate connectivity between the lack of rainfall in the Horn of Africa, particularly in Somalia and Northern Kenya and ultimately the mass displacement of people, which has exacerbated the social and political conflict that already characterizes the region. While the region is historically known for its fluctuating climate conditions, all evidence indicates that these circumstances are becoming more severe in recent decades as a result of the altering global climate. The effects of regional climate change have ultimately begot a situation of forced displacement and migration of peoples either to urban centers (climate change IDPs – internally displaced persons) or across international boarders (climate change refugees). This profound movement of people is inciting further conflict in areas already plagued by political instability and weak governmental control, and has put a severe drain on limited local resources (both economic and food). These increased nodes of viable conflict can be seen at multiple levels, with an increase in communal and clan-based violence in this region to the militarization of IDP and refugee camps (particularly in Northern Kenyan), which is one factor that impelled the Kenyan Government to invade Somalia on October 16, 2011 (Zenko, 2011). However, there is no question, that these increased incidents of conflict (which have the potential of propelling the two states and perhaps the region into a dire and destabilizing conflict), have been dramatically exacerbated by the effects of climate change, and when coupled have created the current regional crisis, which so far has displaced over a million people (UNHCR, 2011) and has put an estimated 150,000 to 300,000 (“SOMALIA”, 2011) at risk of starvation. |

Duration Begin Year: 1991 |

| Location

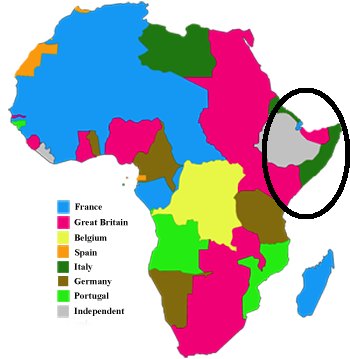

Continent: Africa |

Actors

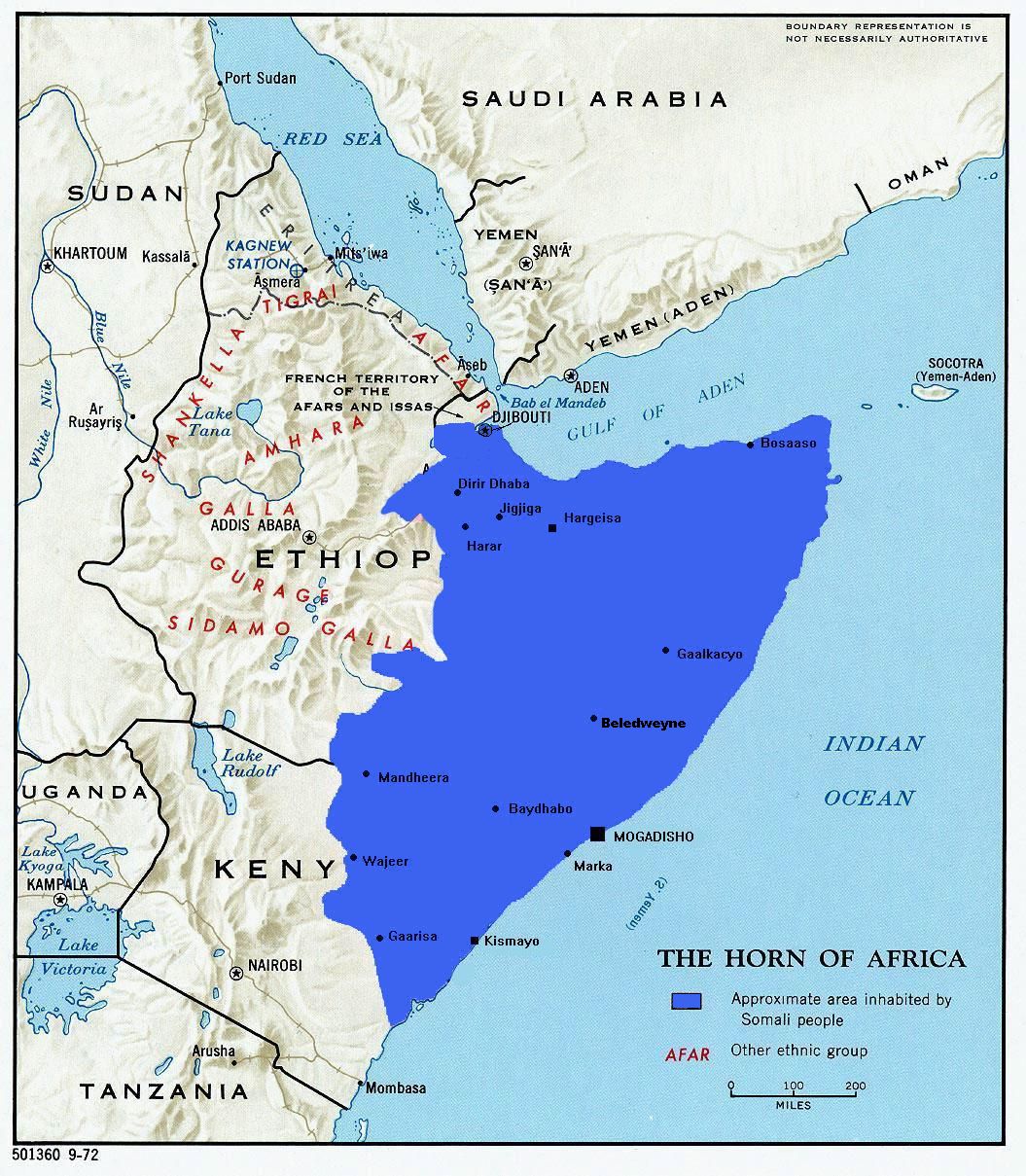

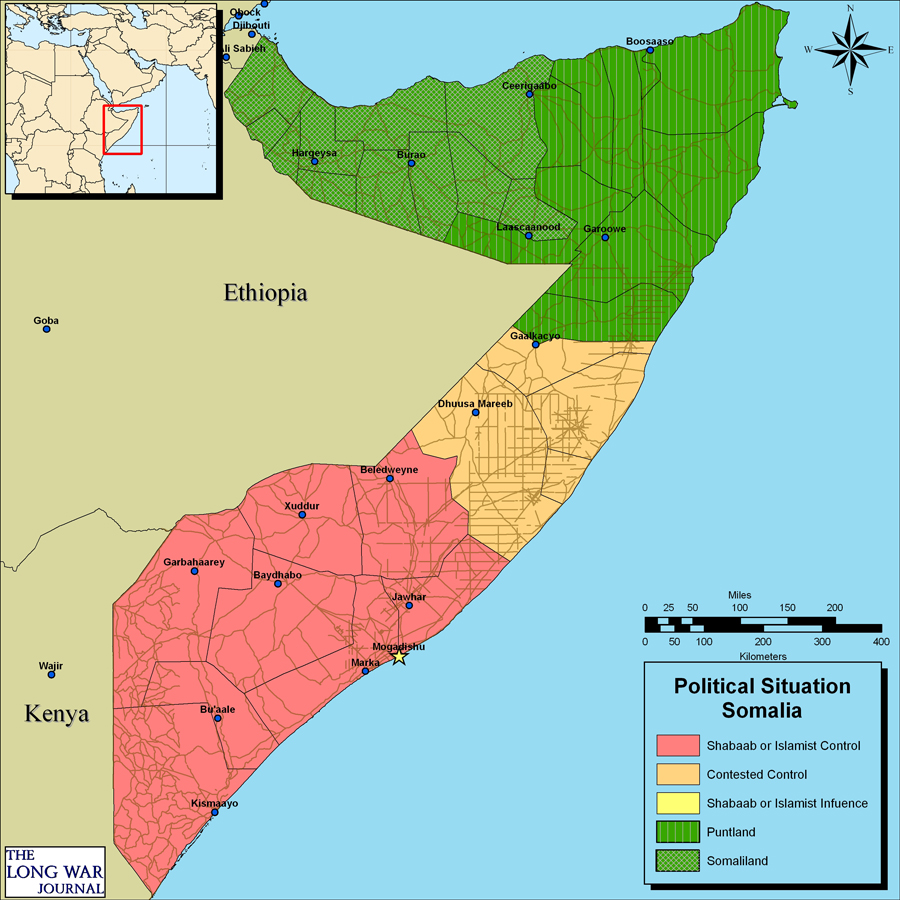

There are a multitude of actors in this conflict including both sovereign and non-sovereign actors. The Kenyan Government is a main actor sovereign actor, who has exhibited little strength in maintaining the border region, but has recently invaded Somali national territory. Additionally, this conflict engendered many non-sovereign actors working in the region to either mitigate or exacerbate tensions. These non-sovereign actors include, Al-Shabaab and clan warlords who have asphyxiated much of the economic and political capacity in the region and have exacerbated the conflict and tensions due to their illegal arms trade and the militarization of pastoralists and refugees communities in the region. Additionally, pastoralists, farmers and their respective clans are non-sovereign actors in the region, who have not only suffered from the dramatic impact of climate change, but have also been fighting territorial conflicts since before the time of colonial rule. Moreover, refugees and IDPs have also emerged out of the altering impact of climate change and the increased violence in the region, as non-sovereign actors. Finally, one can see the entrance of foreign aid workers, as well as local assistance programs, prop up in the region due to the extended conflict and particularly food insecurities. These non-sovereign actors are particularly important for the future recovery of the area as they are seeking to abate the conflict and assist those displaced by both the violent conflict and the impact of the drying conditions. |

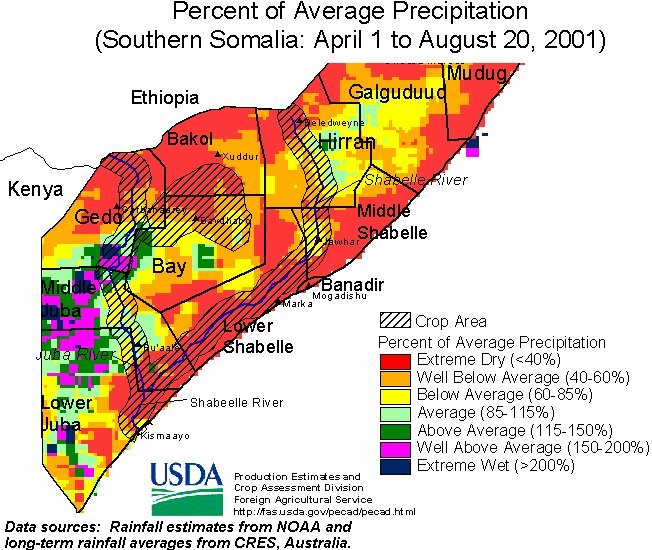

Many projections of climate change in Africa suggest that the continent will face a warming of .2C to .5C per decade (Desanker, 2002) and these warming temperatures will engender erratic rainfall patterns in the region. Eastern African nations, such as Kenya and Somalia, will face increase in overall temperature. One study suggests that the mean annual temperature has increased from 1960-2006 by at least 1°C in Kenya and 1.3°C in Ethiopia, and both countries are experience a higher frequency of hotter days (Oxfam, 2011). While this region does have a history of draught, IRIN estimates that there have been 42 droughts since 1980 (IRIN, 2011). However, currently the periods of drought are becoming longer and more frequent due to the increasing regional temperatures and the decrease in rainfall. “According to surveys of local communities, the climate in the Horn is experiencing an increase in the rates of drought. Reports from the Kenya Food Security Group and from pastoralist communities show that drought-related shocks used to occur every ten years, and now are occurring every five years or less. Borana communities in Ethiopia report that whereas droughts were recorded every 6-8 years in the past, they now occur every 1-2 years” (Oxfam, 2011). It is suggested that from Fenruary to July 2011, the region has experienced rainfall from 2 to 8 inches below normal (Walsh, 2011). These warming climates and lack of rainfall will put a massive stress on the carrying capacity of the land particularly for famers and herders, andwill also beget issues of large-scale droughts procuring dramatic issues of food insecurity for the region.

Due to the region’s extreme dependency on natural resources (such as cattle and crops), the altering of climate patterns have the capacity to put a huge strain on existing resources, particularly with regards to food sources. Studies suggest that the increase in number and severity of droughts in Somalia have cut production of their national consumption needs (IRIN, 2011). Moreover, this increase in regional temperature and decrease in overall rainfall will further cause desertification of the land, which will decrease its carrying capacity and force populations (particularly farmers and pastoralists) to continue to move southward. It is estimated that by 2080, the proportion of arid and semi-arid lands in Africa will likely increase by 5 to 8% (Boko et all, 2007). A recent study suggests that there will be a drastic decrease in the “long rains” (from March to June) from 1980 to 2009 (Oxfam, 2011), which will continue to dry out the land and in ability for framers and herders to participate in their traditional livelihoods. Additionally, this increased pressure on the land will create even more severe food scarcities in the region, due to the inability to grow traditional crops combined with the slow nature or potential inability of the populations in this region to adapt their food production to meet the altering environment (Boko et all, 2007). A report for the IPCC suggests that the length of the growing season will be reduced, for some countries by as much as 50% by 2020, which could lead in a drop of crop net revenues by up to 90% by 2100, which would predominately effect small scale farmers (Boko et all, 2007). It is predicted that Eastern Africa may lose up to 20% of the growing period of key crops by the end of this century (Oxfam, 2011). This is particularly worrisome in countries, such as Somalia, Kenya and other nations in the Horn of Africa who are extremely dependent upon rain-fed crops such as: corn, wheat, teff, sorghum and beans as their staple source of food and income. It has been suggested that in Somalia and Northern Kenya, where food and income generation are already extremely limited, this changing nature of farming and land use could spiral into a devastating humanitarian crisis. “The United Kingdom's Division for International Development projects that crop yields of rice, maize, and wheat will fall up to 10 percent in Somalia and across the Sahel region by 2030” (Stimson Center, 2011). Moreover, reports from Oxfam suggest that by the end of this century the capacity to grow beans (one of the major crops and staple foods) will decrease by 50% in the East African region (Oxfam, 2011).

The stifling of crop production in this region has fostered and will continue to generate situations of dire famine. “Nancy Linborg, an official with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), told a Congressional committee that more than 29,000 children under the age of 5 had died over the past three months in Somalia, thanks to the famine. If conditions worsen—and there's little reason to expected that they won't— upwards of 800,000 may die of hunger and other causes” (Walsh, 2011). Moreover, as previously mentioned famine-like conditions in Southern Somalia has forced populations across national borders, creating dire conditions of hunger and extreme poverty, particularly in the Garissa District of North East Kenya, home to Dadaab refugee camp. The current drought clearly connects to the severe drying conditions created by the La Niña phenomenon**, which lasted from June of last year to this May in the Pacific Ocean (Walsh, 2011). However, in 2007 the IPCC suggested the Eastern African region may in the future experience more intense rainfall as a product of the El Niño phenomenon, which will have the capacity to erode much of the land.El Niño has been accused of carrying more sporadic and dramatic rainfall patterns to the region. This has made the monsoon season irregular and often far more intense procuring large-scale floods, massive destruction of infrastructure as well as modifying the planting season (Walsh, 2011). |

Type of Environmental Problem Climate Change |

Type of Habitat Semi-arid pastoral region |

Act and Harm Site N/A |

Type of Conflict Internal conflict (Somali Civil Conflict) While it can be argued that the root of this conflict falls under the auspicious of an internal conflict in the form of the Somali civil conflict, it can also be considered an interstate conflict, which was illuminated by the October 2011 Kenyan invasion of Southern Somalia. Moreover, while the source of this interstate confrontation can most notably be attributed to conflict spillover from the Somali civil war this confrontation has further exacerbated the aforementioned underlying territorial tensions between semi-nomadic pastoralists in Northern Kenya and Southern Somalia as well as by the changing climate. The multiple nodes of conflict highlight the crisis in the Horn and have drastically impacted regional tensions that date back to before colonization. |

Level of Conflict When considering the interstate conflict between Somalia and Kenya, there has been chronic instability in this region (Northern Kenya and Southern Somalia), which steams from larger state issues such as resource scarcities, lack of viable infrastructure or political control and endemic poverty in the region. However, when considering the trigger of the Kenyan-Somali conflict, the regional conflict spillover seems most aptly at the root of the Kenyan authorities decision to invade the Southern Somali region. The key triggers therefore would be directly correlated with the Somali civil conflict and the lack of tangible stability in the country. The specific trigger points can most likely be identified as:

These trigger effects lie at the origins of the bilateral conflict, and therefore assist in the assessment that this conflict would be considered a high level. |

Fatality Level of Dispute (Military & Civilian Fatalities) High

Death tolls in the region based on the famine alone have reached 300,000 and when combined with estimates on conflict-related deaths, could total upwards of a half million people. Estimates range dramatically in number of casualities of this conflict. This is primarily due to the intricate nature of the conflict as well as its dire implications. Additionally, the lack of a viable central authority in Somalia (since the dimise of the Siad Government and the inability of aid workers and foreign authorities to enter the region) has made hard numbers virtually non-existant. However, some have projected that the the Somali civil conflict has procured a death toll of roughly 550,000 people from the year 1991 to 2004 (Scaruffi, 2009). This figure however, does not include the vast numbers of innocent people who have lost their lives to worsening famines. Some sources suggest that in past years famines have claimed numbers reaching 300,000 people (Berry, 1991). Most interestingly, prior to the current drought and subsequent famine the worse recorded cause of famine for the Somali nation was in the early 1990s, correlating with the collapse of the Siad Government and complete chaos that enveloped the country afterward. Current estimates place death tolls in the stratosphere when compared to past spouts of regional famine. Classified as the worst drought in 60 years, some reports indicate that over 29,000 Somali children under the age of 5 have perished and roughly 640,000 children are acutely malnurished (Nor and Straziuso, 2011). Moreover some statistics estimate that 3.7 million Somalis are living in crisis and 2.8 million of those are living near the southern border with Kenya and Ethiopia. Moreover, as many as 750,000 Somalis could die in the upcoming months due to extreme drought and famine conditions, none the likes of which this region has experienced. (World Vision 2011). Finally, while the combat death toll has remained steady particularly between clan conflict and Al-Shabaab militants, and the number of civilians losing their lives daily to starvation has jumped dramatically forcing a mass exudous of people. Most specifically those fleeing Somalia and entering Kenya's refugee camps. Dadaab, which has witnessed up to 3,500 peoples per day seeking refuge (Care, 2011). |

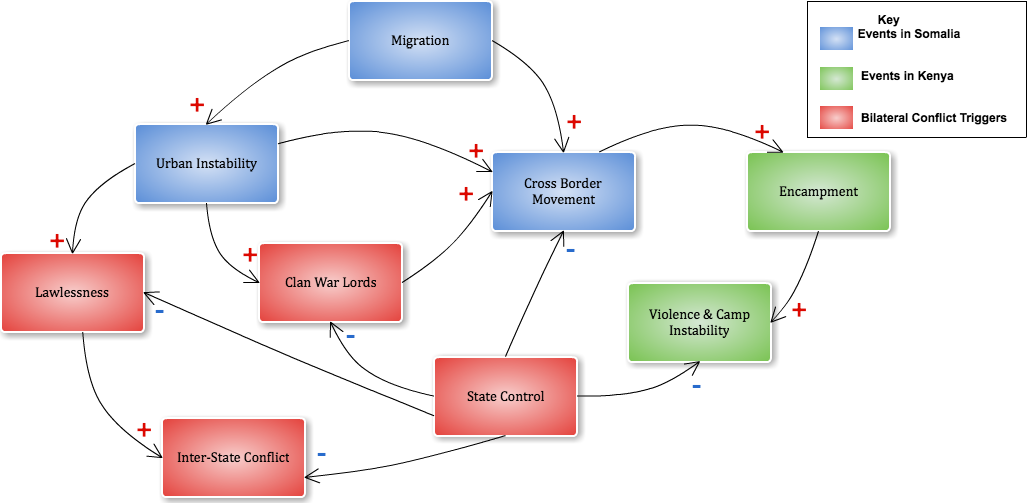

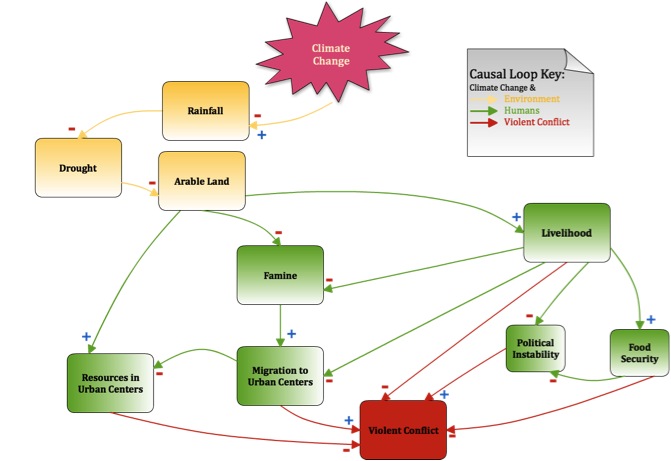

Since this conflict has roots in civil conflict, but is truly examining the interstate confrontation, it seemed essential to consider the overlap both locally in the context of the Somali civil conflict and then bilaterally, which will look at the overlap in environment and conflict in the Kenyan Somali conflict context. Environment-Conflict Link & Dynamics Somali Civil ConflictThe causal loop below demonstrates the intricate correlation between the current conflict in Somalia and changing climate that is dramatically affecting the region. The diagram is siphoned into three different, but highly interconnected sections: the effects of climate change on the earth, the effects of climate change on humans in relation to migration, political stability and livelihood and finally the effect of climate change on human conflict. Below describes the relationship between these moving components that are clearly not mutually exclusive.

While this causal loop examines the interaction between the

different moving parts linked to draught, famine, migration and

conflict in Somalia, there is also a profound systems behavior that is

occurring. In the case of Somalia, there is already an underlying

condition of endemic poverty that is an integral component of the system

and underpins many of the already existing facets, such as government

instability, lack of resources and livelihood. This is essential when

examining the causal loop because with this ever-increasing statistic

regarding overall poverty generates conditions for more violent

conflict, which compounds the situation of draught and

migration.Bilateral Interstate (Somali-Kenyan) Conflict This causal loop demonstrates the dynamics between to the events that are occuring in Somalia (particularly as seen with the Somali civil conflict) and how these interactions are impacting their neighbor (Kenya), and to this end are inciting the Kenyan Somali conflict. |

Level of Strategic Interest State |

Dispute Outcome In Progress |

Related ICE and TED Cases Case #46 -Ethnic Cleansing and the Environment in Kenya Case #225 -Climate Change, GMO's and Conflict Process in Uganda by Dillon T. Klepetar Case #227 -Zambia Peace Park by Oana Leahu-Aluas Case#240 -Botswana: Desertification & Drought by Nicholas Sabato |

Relevant Websites and Literature "Al Shabab." Times Topics - The New York Times. 17 Oct. 2011. Web. 12 Nov. 2011. <http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/organizations/s/al-shabab/index.html>. Daily Nation (Nairobi), "Aid crisis as Somali (accessed June 29, 2011). Bariagaber, Assefaw. Conflict and the Refugee Experience. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006. Print. Berry, LaVerle. "Ethiopia - Ethiopia in Crisis: Famine and Its Aftermath,1984-88." Country Studies. Ed. Thomas P. Ofcansky. Library of Congress, 1991. Web. 04 Dec. 2011. <http://countrystudies.us/ethiopia/35.htm>. Brown, Ben. "Horn of Africa Tested by Severe Drought." BBC - Homepage. 4 July 2011. Web. 8 Nov. 2011. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-14023160>. Care. ""The Worst Crisis in the World Today" Lives Hang in the Balance." Care. 5 Sept. 2011. Web. 12 Nov. 2011. <http://www.care.org/emergency/Horn-of-Africa-food-poverty-crisis-Dadaab-2011/index.asp>. Desanker, Paul V. Center for African Development Solutions. World Wildlife Fund. “Impact of Climate Change.”Johannesburg, South Africa. <www.worldwildlife.org/climate/Publications/WWFBinaryitem4926.pdf>. "Fleeing Somalis Struggle To Find Shelter At The World's Largest Refugee Camp." Doctors Without Borders. <http://www.doctorswithoutborders.com/news/article.cfm?id=5371&cat=field--news> Web 1 July 2011. Gettleman, Jeffrey. "Somali Militants Threaten Kenya Over Cross-Border Troops." The New York Times. 17 Oct. 2011. Web. 7 Nov. 2011. <http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/18/world/africa/somali-militants-vow-to-attack-kenya.html?_r=1>. Horst, Cindy. Transnational Nomads: How Somalis Cope with Refugee Life in the Dadaab Camps of Kenya. New York: Berghahn, 2006. Print. IRIN. "HORN OF AFRICA: Fast Facts about the Drought." IRIN • Humanitarian News and Analysis from Africa, Asia and the Middle East - Updated DailIRIN, 5 Aug. 2011. Web. 04 Dec. 2011. <http://www.irinnews.org/report.aspx?reportid=93426>. "IRIN Africa | SOMALIA: Number of drought-displaced arriving in Mogadishu "dropping" | Somalia | Early Warning | East African Food Crisis | Environment | Food Security | Natural Disasters | Refugees/IDPs." IRIN • humanitarian news and analysis from Africa, Asia and the Middle East - updated daily. N.p., 11 Aug. 2011. Web. 14 Sept. 2011. <http://www.irinnews.org/report.aspx?reportid=93446>. Kron, Josh. "Somalia." Times Topics - The New York Times. 3 Nov. 2011. Web. 12 Nov. 2011.<http://topics.nytimes.com/top/news/international/countriesandterritories/somalia/index.html>. Menkhaus, Ken. Kenya-Somalia Border Conflict Analysis. Publication. Washington, DC: USAID, 31 Aug. 2005. Print. Menkhaus, Ken. "The Raise of the Mediated State in Northern Kenya: the Wajir Story and Its Implications for State-building." Afrika Focus 21.2 (2008): 23-38. JSTOR. Web. 10 Nov. 2011. Nor, Mohamed, and Jason Straziuso. "29,000 Somali Children Under 5 Dead In Famine: U.S. Official." The Huffington Post. The Huffington Post, 4 Aug. 2011. Web. 04 Dec. 2011. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/08/04/somalia-famine-children-dead_n_917912.html>. Odhiambo-Abuya, E. "United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and Status Determination Imtaxaan in Kenya: An Empirical Survey." Journal of African Law 48, no. 2 (2004): 187-206. Provost, Claire and Hamaz Mohamed. "Dadaab refugee camps: 20 years of living in crisis." The Guardian, March 24, 2011. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/global--development/2011/mar/24/dadaab--refugee--camps--living--in--crisis> Web 28 June 2011. Scaruffi, Piero. "Wars and Casualties of the 20th Century." Piero Scaruffi's Knowledge Base. 2009. Web. 04 Dec. 2011. <http://www.scaruffi.com/politics/massacre.html>. Sheikh, Abdi . "Somalia clashes kill 138 in two weeks -rights group." Reuters, January 15, 2010. http://madaale.com/?p=145 (accessed June 28, 2011). Stimson Center. "Climate Change and Famine in Somalia | Spotlight | The Stimson Center | Pragmatic Steps for Global Security." The Stimson Center | Pragmatic Steps for Global Security. Stimson Center, 9 Aug. 2011. Web. 14 Sept. 2011. <http://www.stimson.org/spotlight/climate-change-and-famine-in-somalia/>. "The Regional Impacts of Climate Change." IPCC - Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Web. 12 Nov. 2011. <http://www.ipcc.ch/ipccreports/sres/regional/index.php?idp=11>. UNHCR. "UNHCR - Somalia." UNHCR Welcome. http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e483ad6.html (accessed September 14, 2011). UNHCR Dadaab Camp Population Statistics, 26 June 2011. Walsh, Bryan. "El Nino, La Nina, Climate Change and the Horrific Drought in Wasara, Samson S. "Conflict and State Security in the Horn of Africa: Militarization of Civilian Groups." Africa Journal of Political Science 7.2 (2002): 39-60. Web. 9 Nov. 2011. World Vision. "Somali Famine Reaches Historic Level." Sponsor a Child. World VIsion, 22 Sept. 2011. Web. 04 Dec. 2011. <http://www.worldvision.org/home.nsf/home/world-vision-news/famine-in-somalia-2-1426?Open>. Zenko, Micah. "What's Wrong With Kenya's Invasion of Somalia - Micah Zenko - International - The Atlantic." The Atlantic — News and Analysis on Politics, Business, Culture, Technology, National, International, and Life – TheAtlantic.com. 28 Oct. 2011. Web. 10 Nov. 2011. <http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/10/whats-wrong-with-kenyas-invasion-of-somalia/247517/>. |

*The Harakat Shabaab al-Mujahidin (al-Shabaab)—also known as al-Shabaab, Shabaab, the Youth, Mujahidin al-Shabaab Movement, Mujahideen Youth Movement, Mujahidin Youth Movement, and other names and variations—was the militant wing of the Somali Council of Islamic Courts that took over most of southern Somalia in the second half of 2006. Although the Somali government and Ethiopian forces routed the group in a two-week war between December 2006 and January 2007, al-Shabaab––a clan-based insurgent and terrorist group––has continued its violent insurgency in southern and central Somalia. The group has exerted temporary and, at times, sustained control over strategic locations in southern and central Somalia by recruiting, at times forcibly, regional sub-clans and their militias, using guerrilla asymmetrical warfare and terrorist tactics against the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) of Somalia and its allies, African Union peacekeepers, and nongovernmental aid organizations. For more info: http://www.nctc.gov/site/groups/al_shabaab.html **La Niña is characterized by unusually cold ocean temperatures in the Equatorial Pacific, compared to El Niño, which is characterized by unusually warm ocean temperatures in the Equatorial Pacific. To read more about La Niña and El Niño please look at: http://www.pmel.noaa.gov/tao/elnino/la-nina-story.html |

ronment (i.e. generating a more dramatic raining season as well as a much more dire dry season).

ronment (i.e. generating a more dramatic raining season as well as a much more dire dry season).