|

ICE Case Studies |

The Impact of the Asian Tsunami on Southern Thailand Religious Strife Erin Teeling |

I. Case Background |

![]()

Map of Thailand |

|

| Source: CIA World Factbook |

I. Case Background

I. Case Background

|

| The Tsunami at Ao Nang, Thailand |

The four southern provinces of Thailand have been plagued by Islamic separatism and insurgency since the 1900's, when Thailand formally annexed the areas of Narathiwat, Patani, Songkla, and Yala. Formerly part of the Kingdom of Patani, this Malay region has been practicing Islam since the mid 13th century. Because Thailand’s population is 95% Buddhist, the Muslim-dominated southern provinces seem to feel greater ethnic, religious, and linguistic ties with their Malaysian neighbors than with their Thai central government. The Muslims of Southern Thailand have continuously expressed their discontent with the Thai government on the bases of discrimination, neglect, and unequal economic opportunity through the form of violent insurgencies, bombings, and terrorist attacks, blaming the central Thai government for the lack of development in Thailand’s southern sector. While some of these claims, particularly complaints of underdevelopment in economic sectors throughout southern Thailand, are valid concerns, the Muslims have not reacted in a proactive or cooperative fashion. Instead, by revolting against the central government, they have, in effect, isolated their communities and worsened their plight. Violence eased in the 1990s with increased border security between Thailand and Malaysia and with promises for increased funds from the Thai government. However, insurgency reared its head again in the beginning of 2004, the most violent year of this internal Thai conflict. While the December 26, 2004 tsunami, which claimed the lives of at least 283,000 people, brought cease-fires and moments of peace in other regional ethn`ic conflicts (such as with the Muslim insurgents in Aceh, Indonesia), violence in southern Thailand persisted. The Thai government was forced on January 3, 2005 to deploy some 10,000 troops to southern Thailand in order to quell threats of violent insurgency even in the midst of tsunami relief efforts. The tsnuami devasted communities in southern Thailand whose livelihoods depended on the land and the sea for resources. The sudden destruction of fishing boats, coral reefs, and homes, destroyed livelihoods and left many Thai Muslims homeless. This worsened the Muslim-Buddhist conflict in Thailand, as many out-of-work Muslims resorted to violence in order to have their concerns heard by the government. In addition, because the Thai government responded slowly in some Muslim regions following the tsunami, feelings of resentment increased within the Muslim community, as many Muslims felt neglected by their government in a time of need. Even now, almost a year and a half after the tsunami, violence continues in southern Thailand despite Prime Minister Shinawatra's efforts to quell revolts in the former Patani Kingdom. Until the Royal Thai Government can gain the trust of Thai Muslims, separatist violence is bound to continue.

In 1902, the Patani Kingdom was officially annexed and merged with Thailand.

Thailand: Location of the majority of the action.

Malaysia: Thailand's border nation; has had historic border conflicts with Thailand. Also, Thailand's Muslim, population, the Malays, finds its religious and cultural roots in Malaysia.

Great Britain: A minor player, the Thai Muslims appealed to Great Britain for support for their community when the Patani Kingdom was being merged with the rest of Thailand. Also, the Anglo-Thai Agreement (1949) placed the Thailand-Malaysia border area under the joint control of Great Britain and Thailand, helping to temporarily quell border violence between the two countries.

Muslim Separatist Groups: responsible for much of the violence occurring in Southern Thailand today. Among these are underground organizations linked to international terrorist groups, such as Al Qaeda and Hezbollah.

International Relief Organizations: Played a major role in helping Thais recover from the destruction caused by the tsunami.

![]()

II. Environment

Aspect

II. Environment

Aspect

|

|

Satellite images of Thailand's Western coast before and after the tsunami. Source:UNOSAT |

|

| Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

On December 26, 2004, a massive earthquake with a magnitude of 9.3 rifled through the Indian Ocean floor 150 miles off the coast of Sumatra. This earthquake, the second largest ever recorded, lasted almost eight minutes, in contrast to more typical earthquakes in Japan or California, which normally last only a matter of seconds. Caused by the gradual collision of two tectonic plates along the 745 mile Andaman-Sumatran ocean trench, this earthquake resulted in a colossal tsunami, or tidal wave, which ripped through the region of South Asia. The countries of Indonesia, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Myanmar, India, Seychelles and Somalia were among the nations hit by the tsunami, with the island of Sumatra bearing the brunt of the disaster. Billions of tons of seawater caused waves of up to 65 feet in height, causing tens of thousands of deaths in the city of Banda Aceh in just fifteen minutes. (1)

All together, the earthquake and subsequent tsunami caused at least 283,000 thousands deaths throughout the Indian Ocean region, with Thailand alone suffering some 5,395 deaths. According to the Thai Ministry of Interior Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation, 2,059 of these deaths were Thai people, 2,436 were foreigners, and another 900 deaths were unidentified. In addition, another 2,845 people were declared missing and 8,457 Thais and foreigners were injured.(2) Further, 400 Thai fishing villages were destroyed, ruining the livelihood of thousands of people living in the south and west of Thailand, many of whom are Muslims. The tourism sector, a major economic asset for Thailand, was also adversely affected, causing another 120,000 people to lose their jobs. (3) The destruction was so severe in Thailand that nearly 3,000 homes were destroyed, with another 2,000 severely damaged, forcing some 2,900 people to still be living in temporary shelters by September of 2005, nearly one year after the tsunami.(4) In all, Thailand was the second most financially affected country, suffering some $2.09 billion in damage.(5)

Human Damage in Thailand from 2004 Tsunami |

Deaths | Injured | Missing |

| Foreignors | 2,436 | ||

| Thais | 2,059 | ||

| Unidentified | 900 | ||

| Total | 5,395 | 8,457 | 2,845 |

|

| Destruction in Phuket and Phang Nga, source: UNDP |

Environmental Concerns

Aside from the human fatalities and infrastructural destruction, a major concern following the tsunami was environmental damage, as Thailand is home to “some of the world’s most diverse coral reef ecosystems”. Some 35,000 tons of debris and hazardous material were littered across the western coast onto the beaches, coral reefs, and sea grass meadows. It is estimated that 13% of all Thai coral reefs were affected by the tsunami, with some western costal reefs suffering up to 80% damage. Further, with coastal areas flooded up to 2 miles inland, surface water and groundwater were significantly contaminated with seawater, sewage, and other waste. Not only did this impact the Thai people’s access to clean water, but it also affected vegetation and fertility of soil, with about 1,500 hectacres of agricultural land being destroyed and damaged.(6)

Relief and Reconstruction

The Thai government, more than one year after the tsunami, is still dedicated to reconstruction and rebuilding in the wake of this disaster. Although the speed and intensity of relief and reconstruction responses varied by location, it is believed that overall, the Thai government’s efforts have been thorough, efficient, and effective. A top priority in reconstruction efforts is the recovery of the tourist industry, which is a key source of income for Thailand. According to Paul Bishop and a geographical research team from the University of Glasgow, Scotland: “…we were told…that rebuilding costs could be recouped in a few good years of tourist income, and so there is every motivation to rebuild quickly, cheaply, and perhaps with as few regulatory controls as possible. “(7)

Relief efforts have been intense, with assistance coming from the Thai government, private sector institutions, NGO’s, multilateral institutions such as the United Nations, and individual governments. According to the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the first relief teams arrived to affected areas merely 6 hours after the tsunami struck. “By January 9, an estimated 90,000 persons in affected communities, relief centers, and displaced-person camps had received medical and mental health care.”(8) Thanks to organizations such as UNICEF, 75% of the children affected by the tsunami were able to return to school within two weeks of the disaster, as permanent and temporary school structures were urgently rebuilt. In addition, over 150,000 children benefited from psycho-social support programs, enacted by UNICEF.(9) Public donations helped provide the people affected by the tsunami with food, bottled water, and clothing, while volunteers from Thailand and also other countries helped assemble shelters in town halls, schools, and other vacant lands. Thailand’s Ministry of Public Health was able to immediately mobilize more than 200 doctors to affected areas, offering immunizations for children, and overall “disease surveillance”, focusing on preventing the spread of communicable diseases and health issues caused by flooding and contamination, such as dysentery, diarrhea, cholera, typhoid, food poisoning, and hepatitis.(10)

Within ten days of the disaster, the Thai Immigration Bureau had assisted almost 5,000 tourists to return home, with the Thai government providing emergency assistance of $243 for each foreign tourist, in addition to accommodation, food, and transportation.(11) The Royal Thai Government also offered compensation for local victims, giving financial assistance to some 285,000 Thais by November of 2005. Various amounts of assistance were given to families who lost their principal breadwinner, suffered a loss of life, encountered serious injuries, became disabled, encountered funeral expenses, and endured the loss of their livelihoods. In addition, more general compensation was given to people to help people purchase basic necessities for rebuilding homes. Long term recovery is now aimed at reestablishing the livelihoods of fishermen and those involved in the tourist sector, with significant financial compensation being awarded to small businesses.(12)

Early Warning System

| Click below for the UNIOC Communications Plan for the Indian Ocean Advisory Service |

|

| The UNIOC is developing an early warning system to protect against future tsunami disasters. |

|

| Early Warning System? |

In addition to reconstruction, efforts are being made to prevent future disasters

of this nature. Lack of information and slow notification of people in South

Asia largely contributed to the destruction caused by the tsunami. The absence

of a proper warning system denied people the time necessary to evacuate endangered

areas. Because it is believed that thousands of lives could have been saved

by the presence of such a system, the United States and the United Nations Intergovernmental

Oceanographic Commission (UNIOC) developed a two-year, $16.6 million project

to develop an Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System, which will cover all aspects

of early warning processes, including technical assistance for initial hazard

detection as well as local community-level responses to warning messages. According

to Timothy T. Beans, Regional Director for USAID Regional Development Mission:

Asia, this early warning system will utilize “expertise from USAID, the National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), US Geological Survey (USGS),

US Forest Service (USFS) and the US Trade and Development Authority (USTDA),

the program will strengthen disaster preparedness and response systems as part

of a multi-hazard ‘end-to-end’ framework”.(13)

The system will involve a system of contacts between countries that will be

designated to receive periodic bulletins from a series of sea-level stations

throughout East Africa, Southeast Asia, and southern India. Bulletins will include

information such as earthquake magnitude and a ranking of the sea earthquake

as local, regional, or ocean-wide, with an ocean-wide warning being the most

extreme, with possible life-threatening effects through the whole ocean region.

A local-level tsunami is one with destructive or life threatening effects usually

limited to within100 km of the epicenter, and a regional tsunami is one with

life threatening effects usually limited to within 1000 km of the epicenter.

(info from UNIOC report link above).

Launched on August 17, 2005, it is hoped that international collaboration in this program will help prevent the destruction and fatality caused by the 2004 tsunami in future natural disasters, particularly in Indonesia, Thailand, Sri Lanka, India, and Maldives.

All is not Well

Although recovery from the disaster has been surprisingly rapid, with generous responses from many levels of government, NGO, and private associations creating a “geography of generosity”, as described by researcher Nigel Clark,(14) not everything in the wake of the tsunami ended peacefully. While the 2004 disaster brought moments of peace and neutrality to other ethnic conflicts in violent areas such as Aceh, Indonesia, the violence that erupted in early 2004 among the Thai Muslim community persisted even in the wake of destruction. Due to the concentrated loss of livelihood among the Muslim community, and delayed relief reactions in certain impoverished ethnic communities, the overlap between the Muslim conflict and the tsunami caused extreme violence. This conflict continues today, and unlike the destruction caused by the tsunami, little relief is in sight.

III. Conflict

Aspects

III. Conflict

Aspects

From Ethnic Conflict: Approximately 5,000 military and civilian (from 1902-present)

Direct Result of tsunami: 5, 395

1457 |

Islam becomes state religion of Patani Kingdom |

1899 |

Rama V integrates outer provinces into the Thai administration |

1901 |

Muslim leader of Patani appeals to British for help, but is ignored. |

1902 |

Patani officially annexed into the Thai Kingdom |

1910-1911 |

Religious hostilities begin |

1921 |

RTG issues the Compulsory Primary Education Act |

1922 |

Execution of Muslim leaders and death of protestors in violence resulting from the Primary Education Act |

1923 |

Another protest breaks out when RTG was accused of closing Muslim vernacular and Quranic schools |

1924-1928 |

RTG tries to lessen southern violence by focusing on economic development and "national belonging" |

1939 |

Thai Custom Decree issued, banning Muslim culture and language |

April 3, 1947 |

the PPM sends a letter to RTG trying to lay the foundation for an autonomous Patani state |

September 9, 1947 |

The homes of 40 Muslim families were burned by Thai police units |

January 16, 1948 |

Muslim leaders were arrested and accused of treason, inciting riots all over the region |

April 26, 1948 |

Dusun Niyur: 400 Malays and 30 Thai policemen killed in Narathiwat; up to 6,000 Muslims fled to Malaysia |

January 1949 |

Anglo-Thai Agreement: joint control by RTG and Great Britain of the border between Thailand and Malaysia |

1960's |

Fall in rubber prices, economic suffering in Malay community |

1970s |

RTG offers special privileges to Muslims in efforts to quell violence |

October 14, 1973 |

Massive student-led insurrection |

December 1975 |

"Patani Massacre": Five Muslim youths murdered by Thai soldiers; beginning of a 45-day demonstration by Muslims at the Patani Central Mosque, which resulted in the death of 25 Muslims |

October 6, 1976 |

Military seizes control of government; period of suppression |

1976 |

Thai-Malaysian Border Agreement |

1990s |

RTG promises increased funds to Malays, violence subsides |

July 8, 2002 |

A bomb explodes on a train in Southern Thailand |

July 10, 2002 |

2 policemen killed in an attack by Malays |

January 4, 2004 |

Militant Muslims attacked an army base near the Malaysian border, killing 4 soldiers and stealing weapons. This started an uprising where 500 people were killed. 18 schools were burned down. |

October 2004 |

85 Muslims killed in a peaceful protest of 2,000 Muslims outside a police station |

April 28, 2004 |

30 people killed in a raid on a mosque; 100 Muslims killed in related violence |

January 1, 2005 |

10,000 Thai troops deployed to the south |

| March 1, 2005 | Car bombing kills 5 and injures 44. |

July 2005 |

RTG declares emergency rule in the south |

The conflict continues today, with over 800 people dying since the 2004 outreak of violence. |

|

History of Violence

Although the Thai government has made attempts to enhance the standard of living of the southern Thai Muslims in recent years through increased political representation, educational reforms, efforts at economic development, and improved infrastructure, historical distrustful sentiments of the central government by the Thai Muslims runs deep. In 1902, the Thai Kingdom annexed the Patani region and incorporated it into the centralized Thai government. This group of provinces had officially been practicing Islam since 1457, but the unofficial practice of Islam in this region dates back to the 13 th century. During this period, Islam spread to Asia through the spice trade, with Muslim communities popping up along spice trade routes. In Southeast Asia, Indonesia was the first country to be influenced by Islam, however, the religion spread relatively quickly through Thailand and Malaysia, as well. After Bangkok deposed and imprisoned Patani leaders, subordinates of the seven annexed provinces began a collective resistance movement marked by boycotts of Thai government meetings and actions aimed at preventing newly-appointed Thai-Buddhist bureaucrats from performing their duties.(15)

Despite resistance efforts, the people of the Patani region were unsuccessful at maintaining their sovereignty, and their provinces were regrouped into four provinces that make up the southern portion of Thailand today: Narathiwat, Patani, Songkla, and Yala. After formally integrating these provinces with Thailand’s central government, Bangkok proceeded to replace local Islamic law, sharia and adat, with Thai laws. This angered the Thai Muslims, as the sharia and adat formed the core of their religion and culture, and thus was extremely valuable to the Patani Muslims.(16)

Forceful integration of the Thai Muslims continued well into the 1900’s, making significant progress with the 1921 Compulsory Primary Education Act. This law required all Thai Muslim children to attend Thai primary schools, which promoted the use of the Thai language among the Thai Muslims. To the Muslims of southern Thailand, this was seen as an effort to “stamp out their religion and culture”, as it was “crucial that their young children should not be exposed to education that would divert their attention from the teachings of Islam”.(17) A rebellion ensued, resulting in many casualties and the execution of Muslim leaders. This revolt caused the Thai government to reassess their policies toward the Thai Muslims, and efforts were made to gain loyalties in the Patani region through economic development and political participation.

A 15-year period of relative peace (1923-1938) ended with the nationalistic government of Phibun Songkrahm (1938-1944). The 1939 Thai Custom Decree banned many Muslim cultural and religious practices, as well as the use of the Malay language. Muslims were even forced in some cases to worship Buddhist idols.(18) The distrust of the Thai government felt by the Thai Muslims became apparent during this period when thousands of Muslims fled the region for Malaysia and Saudi Arabia. Violent separatist activity resumed and continued until the Anglo-Thai Agreement for joint control by the British and Thai governments of the Thai-Malaysia border neutralized the conflict. Violence reached its peak on April 16, 1948, when a revolt led by a religious teacher resulted in the death of 400 Malays and 30 policemen and the “flight of some 2,000-6,000 Muslims to Malaysia.”(19)

Tensions rose again in the 1960’s however, when the commodity price for rubber dropped significantly due to improvements of production technologies and a significant rise in the supply of rubber coming from Southeast Asian countries. Because most Thai Muslims find their livelihoods in the rubber tapping and fishing industries, the drop in the price of rubber significantly damaged the economy and standard of living of the Patani region.(20) In order to prevent another violent uprising, the Thai government offered the Patani Muslims special privileges in the early 1970s. Among these concessions were provisions for infrastructure projects, including roads, schools, and colleges in Muslim provinces; the replacement of old rubber trees with a new high-yield variety; irrigation systems and flood control projects; and quotas for admission of Muslims to universities and government bureaucracy.(21) These concessions seemed to appease most separatist violence for several years. Separatist movements were then further repressed with the installation of a military government in October of 1976 and the declaration of martial law in the southern provinces. Further promises of increased funds and economic development kept violence at bay through the 1990s, until the more recent swell of uprisings began in 2002. (See timeline for history of events). This most recent period of violence has been especially disastrous, resulting in the death of hundreds of Muslims by the hands of the Thai government and military forces.

Current Complaints

While it is apparent that the Muslims of southern Thailand suffered from unjust repression and forced assimilation in the early 1900s, what has encouraged the more recent and more intense period of violence that continues today? Muslim complaints are three-pronged.

1. Education Grievnaces

The first grievance lies in the realm of education. Since the 1920’s, the Thai government has emphasized the importance of Thai Muslims learning and using the Thai language, as well as receiving secular education similar to that in the Buddhist majority of the country. However, Thailand’s Muslims have not responded positively to the government’s efforts at secularizing education. Many Muslims feel that the government’s support for secular and centralized education is a method of wiping out Muslim culture and further assimilating the Thai Muslims into Thai society. Other Muslims oppose secular education on the basic premise that religious education is more important. Still others feel that the Thai government is trying to force the Muslims to “deny their religion, historical heritage, race, and customs.”(22)

For most Muslims in Thailand, education is provided by local Islamic schools, Pondok, which, until the Thai government repealed the Thai Custom Decree in 1961, taught no standard Thai curriculum, including language. When the Thai government offered monetary incentives to Pondok schools that participated in Thai curriculum, teachers and headmasters protested all over the region, cautioning that the government “must not close down Pondok schools that do not convert [to centralized curriculum], or convert too slowly.”(23)

While maintaining cultural and religious identity through education has been an important concept for the Thai Muslims, it has also contributed to a limitation of economic and political opportunity in the region. Without learning the Thai language or receiving secular education, Muslims from the south have been unable to compete with northern Thais in politics, higher education, and even white-collar professions. This leads to a second contemporary complaint: a lack of economic development in the Patani region.

2. Economic Inequality

As stated above, most Thai Muslims, due to the location of their communities and because of educational limits imposed on the Muslims by their religion and inequalities between the Muslims and the Buddhists, are involved in commodity trade and industry, particularly rubber tapping, and fishing while Thai Buddhists dominate the upper levels of Thailand’s economic hierarchy. The limited educational opportunities of Muslim children in the southern Thai provinces limit their economic prospects, making “economic advancement correspondingly difficult. Ethnic divisions thus tend to coincide with economic cleavages.”(24) Tensions are further increased by the presence of nikom sang kong eng, government-allocated Buddhist land settlements. Many Muslims fear that these settlements will have significant future impacts on their natural resource and land-based industries and livelihoods. Another economic complaint made by Thai Muslims is that despite the Patani region’s rich supply of natural resources, the Muslims have been unable to reap the benefits because the government and Thai Buddhists “siphon off” the wealth from the Muslims.(25) Whether or not these claims are accurate is debatable; nevertheless, they are prevalent beliefs throughout the Muslim Patani region. It is a fact that the southern provinces of Thailand remain dramatically underdeveloped when compared to the north, and this gives the economic complaints of Thai Muslims significant clout.

3. Royal Thai Government and Discrimination

A third major complaint made by Muslims in Thailand revolves around the administration and government in Thailand. The abundance of Buddhist government officials in the four southern provinces is a major point of contention in the Muslim separatist faction. Many of these officials do not speak the language of the Thai Muslims, and most do not voice or support the ideas of the Muslim groups. Further, complaints by Muslims against the Buddhist government officials are plentiful, and include charges of corruption, persecution, and even “imprisonment of Muslims based on tenuous allegations of banditry or subversion”.(26) Due to the low levels of education in the region, it is uncommon to find a Muslim member of the local administration. Because of this, many radical Muslims separatists refuse to cooperate at all with the government. They go even as far to call on Thai Muslims to refrain from seeking administrative positions.(27) Because of the unwillingness of people in the region to work with the Thai government toward progress, the region has been under martial law for decades.

While these three categories of complaints have their roots in fact, the legitimacy of the arguments made by the Thai Muslims has been lessened due to the violent and often irrational actions of the group. It is clear that education lies at the root of all these problems, as Thai Muslims cannot improve their lot due to their inferior education compared to Thais in northern provinces. Until the history of resentment and distrust between the Muslims in the south and the central government can be remedied, it is unlikely that the people of the southern provinces will be able to make any kind of significant strides toward development and equality.

|

| This flag is a symbol of the Patani Raya, and represents separatism. |

Underground Movements and Links to Terrorism

At least three major underground Muslim groups operate in Thailand today. These include 1) Barisan Nasional Pembebasan Patani (BNPP) or the National Liberation Front of Patani; 2) Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) or the National Revolutionary Front; and 3) Patani United Liberation Organization (PULO) or Pertubuhan Perpaduan Pembebasan Patani.(28)

The BNPP was formed in 1959, and was led by both “traditional aristocrats and religious leaders”. The objective of this group was to restore independence of the Patani region. Members of this group worked toward this goal through political activity and armed guerilla warfare. In the early 1960’s, many Muslim religious students joined the BNPP and contributed to the establishment of overseas bases and associations.

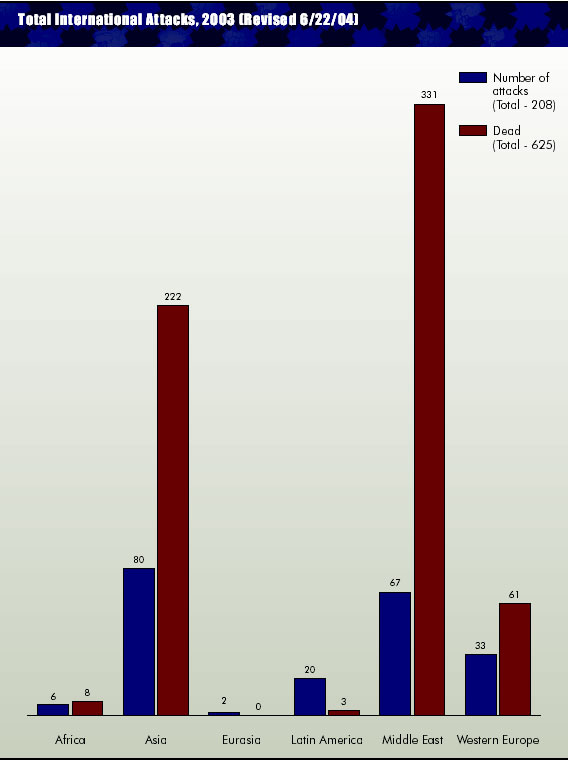

| Total Number of International Terrorist Attacks |

|

| Asia has the most incidents of terrorism, and the second highest number of deaths from terrorist attacks. Source: US Department of State |

In 1963, a more progressive Muslim, Ustaz Abdul Karim Hassan, formed the BRN, aiming to establish a Republic of Patani. This group emerged out of the BNPP because progressive Muslims were hesitant to join the BNPP. BRN leaders “placed greater emphasis on political organization than on guerilla activities.” Because Hassan was the headmaster of an Islamic school, the BRN focused on penetrating the pondok. The BRN succeeded in this, and by 1968 the BRN had significant influence on Islamic schools in Narawthiwat and Yala. This group went underground in 1968, as instances of violence became sporadic and Thai authorities viewed these guerilla groups not as disciplined insurgent groups, but as chaotic gangs.

PULO also emerged in 1968, differentiating itself from BNPP and BRN more orthodox and socialist Islam by focusing on “young, non-committed Patani Muslims by stressing secular nationalism.” This group gained support in Malaysia and India, and among Patani students in other Arab countries.(29)

According to globalsecurity.org,

"The banned Pattani United Liberation Organization (PULO) had boasted

in May 2003 that Thai security forces were 'falling like leaves' as Muslims

fought to free the south from Bangkok's rule. PULO Deputy President Lukman B.

Lima charged that Bangkok 'illegally incorporated' the far south into Thailand

100 years ago and now ruled it with 'colonial' repression while 'committing

crimes against humanity in the area.'"

The apex of guerilla activity occurred from 1970-1975, when the BNPP, BRM, and PULO:

"…set up ambushes and attacked police check-points and government installations. Extortion, especially from rubber and coconut plantation owners, and kidnapping for ransom were also part of their activities. Local Thai businessmen had to pay ‘protection money’ in order to live in peace. Terrorism was often used to remind the villagers and the government of the fronts’ existence."(30)

In a seven year campaign against terrorism (1968-1975), Bangkok battled these underground groups with military operations. These operations incorporated military police and resulted in “385 clashes with Muslim ‘terrorists’; 329 terrorists dead; 165 surrendered to Thai authorities; 1,208 arrested; 1,451 weapons of various types, 27,538 rounds of ammunition, and 95 grenades captured by authorities; and 250 camps destroyed.”(31)

As evidenced by these figures, these Muslim organizations were very dangerous and effectively caught the attention of the authorities. That seven year battle eventually ended with the installation of a military regime in Thailand, and the declaration of martial law in the south. Since then, it is believed that these groups may have developed significant ties with other terrorist organizations, such as Al Qaeda and Hezbollah, although it is unclear how deep these ties run. Ties have been verified with Indonesian group the Free Aceh Movement (GAM), responsible for violent Islamic terrorist activity on the Indonesian island of Aceh. It is clear, however, that many Muslim terrorist leave Thailand to study overseas, where they fall under the influence of radicals and return to Thailand as extremists. In addition, these groups cause additional problems within Thailand as they often resort to drug smuggling and human trafficking with border nations Burma (Myanmar) and Malaysia. To guard against these terrorist activities, Prime Minister Shinawatra reinstated Thailand's intelligence apparatus, which has been working underground to locate and dismantle terrorist groups. This program has had some degree of sucess, evidenced by the successful discovery and prevention of a planned embassy bombing in 2003. In June of that same year, Thai police broke up a cell of the Islamic militant group Jemaah Islamiyah, responsible for bombings of Indonesian resorts. The Royal Thai Government hopes to continue to thwart possible attacks by increased border security and intensified intelligence programs. (For this and more information, please see globalsecurity.org)

Other Problems

Contributing to the conflict in southern Thailand is lack of unity among the Thai Muslims. Underground Muslim groups and factions within the Patani community do not all advocate identical ideals. It seems that there have emerged two distinct parties within the Muslim population in Thailand’s southern provinces, what Astri Suhrke dubs the “loyalists” and the “separatists”. While both parties feel neglected and repressed by their government and desire equality, loyalists maintain that Muslims must “accept Thai rule as legitimate, and that they must work with Thai officials to solve problems of economic development, and administration in the South.” In contrast, separatists maintain that “Muslims will never be able to protect and maintain themselves as a distinct community under Thai rule, and that opportunities for economic self-advancement are stifled…Only by obtaining autonomy or independence can those Muslims who wish to become ‘modern’ do so while still remaining a Thai Muslim.”(32) Raymond Scupin describes a similar dichotomy, that between the “new Muslims”, khana mai, or reformists, and the “Old Muslims”, khana kau, or traditionalists.(33) While Scupin claims that while both groups are fundamentalist or orthodox, the khana mai are more progressive Muslims, who want socioeconomic and political change through reform, similar to Astri Suhrke’s “loyalists”. In contrast, the khana kau remain more steadfast in old-fashioned Muslim ways, and shun modern reforms, similar to Suhrke’s “separatists”. This split among the Muslims of southern Thailand makes it difficult for any progress to be made: without unity, the Thai Muslims cannot fight for a common cause. Instead, their battle appears disorganized, violent, and chaotic. It remains unclear what exactly the Thai Muslims want as a whole, whether it is to secede and become an autonomous nation, to join their brethren as part of Malaysia, or simply to acquire recognition from their government as a unique group with specific rights. Until the Thai Muslims can unite and collectively express their goals, the almost daily occurrences of violence will continue in Thailand’s south with no solution in sight.

![]()

IV. Environment

and Conflict Overlap

IV. Environment

and Conflict Overlap

Causal Diagram:

| Woodworkers Rebuild |

|

| People affected by the tsunami must rebuild their livelihoods |

The Royal Thai Government (RTG) offered financial compensation in the amount of $1,500 to fishermen with registered small boats and $5,000 to fishermen with registered large boats in order to give fishermen the resources needed to rebuild their livelihood. However, as was the case with many poorer Thai fishermen, thousands of boats lost in the tsunami were unregistered. Receiving little or no compensation, these poorer fishermen simply did not have the abilities nor the resources to go out to sea and rebuild their lives.(36) This left thousands of Thai Muslims, many of them migrant workers from the four Muslim southern provinces, with nothing. Magnifying this problem has been a 40% rise in fuel costs since January 2005, “further undermining the viability of small-scale fishing”.(37)

In “Livelihood Conflicts: Linking Poverty and Environment as Causes of Conflict”, Leif Ohlsson explains how a loss of livelihood within a population can lead to violence. Ohlsson maintains that the loss of livelihood can serve as a “missing link” between determining the cause of conflict in the situation of environmental degradation. Ohlsson believes that environmental scarcities, combined with a large degree of societal inequality, and the threat to a group’s livelihood or source of income can be a substantial cause for conflict. In the event of a loss of livelihood, young men, in particular, feel compelled to find another source of income; this often leads to the exploitation of “identifiable ethnic, linguistic, national, or regional cleavages” within a particular society. Unemployed locals may find themselves desperate for subsistence, thus resorting to following a violent warlord in looting and destruction in the hopes of earning money.(38)

Although Ohlsson uses the cases of Rwanda and Kosovo as examples for his theory, the Muslim movement of Southeast Asia in general, and of southern Thailand, in particular, also illustrates his theory. While the Muslims of southern Thailand had been suffering from poverty for years, the sudden destruction caused by the tsunami erased what little legitimacy and stability their livelihoods provided. With thousands of Thai Muslims out of work, violence in the pre-existing structure of conflict between the Muslims and government officials escalated to uncontrollable heights. The violence was such that in January of 2005, the RTG had to deploy 10,000 troops to southern Thailand in order to keep random bombings and attacks on police stations, public transportation, and Buddhist areas under control.

Displacement of People

|

| Muslims were displaced from waterfront homes like these because of the tsunami. Source: International Collective in Support of Fishworkers |

Another overlap between the pre-existing ethnic conflict and the environmental destruction caused by the tsunami is in the area of land claims. According to Astri Surhke, the existence of nikom sang kong eng, or government-allocated Buddhist land settlements has been a major complaint of southern Thai Muslims.(39) In these land settlements, the RTG takes traditionally Muslim lands and hands them over to Thai Buddhists. This further limits the economic development in Muslim areas of Thailand. The threat of this type of land allocation increased after the tsunami, as the destruction of homes and businesses has led to disputes over land rights. Muslim fishermen, relying on ocean resources for many decades, settled on coastal lands long before the booming tourist industry gave them value. Citing that their burial grounds house ancestors two to three generations back, many Muslim communities argue that they settled the land long before the issuance of deeds. Technically illegal squatters, these people lacked proof of ownership of the land. With no housing or business development to mark the land as their own, many Muslims (and other groups of people, as well), were not permitted to return to their original homes, and “risked being moved further inland, to live in houses away from the sea, the source of their livelihood.”(40) These areas of prime real estate were then sold or given to private developers in order to make profits in the rapid reconstruction of the tourist industry. This problem is so extreme that of the 47 villages destroyed by the tsunami, at least 32 of these places are facing such issues of land rights. Unprepared to move to the newly provided RTG-sponsored free public housing miles away from the ocean, many displaced persons decided to return to the locations of their old homes and start rebuilding, despite their lack of proof of ownership of the land or their former homes. Because these homesteads are considered public lands, part of the Forestry Department, National Parks Department, or Treasury Department, the return of fishermen to their original homes has conflicted with newly proposed civic projects, “zoning plans, commercial exploitation, and vested interests”.(41) Homeless and jobless, former Muslim fishermen suddenly became more impoverished than they were prior to the tsunami. With little or no access to justice in the chaos-ridden environmental destruction, many of these people have resorted to violence in order to have their concerns heard.

Resulting Violence

With attacks on government buildings, police stations, and even schools occurring on a near-daily basis, the Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra deployed some 10,000 troops to the southern provinces in January of 2005, immediately following the tsunami.(42) Despite the establishment of an independent panel, the National Reconciliation Commission (NRC), created to recommend actions to lessen the conflict, violence raged through the south in the wake of the disaster.(43) Nothing the RTG did seemed to work: “It has put the police in charge; it has put the army in charge; it has instituted a joint command shared between the two. It has bolstered troop numbers; it has reduced them. It has promised funds for development; it has threatened to withhold them.”(44) Efforts at quelling violence were so disastrous that the NRC has already been largely sidelined, less than a year after its establishment.(45)

Further exacerbating the violence among Muslim groups is the lack of scientific understanding of the causes of the tsunami. According to a group of researchers from the University of Glasgow, Scotland, elderly Muslims believed that the tsunami was “God’s way of telling us that we have sinned”, or that it was the result of “younger Muslims deviating from Islam, consuming alcohol and drugs. As retribution, God sent the tsunami to cleanse the area of sin”.(46) Further causing controversy is the setting up of a tsunami museum on the shore of Koh Phi Phi, a largely Muslim community. Many tsunami survivors do not wish to be constantly reminded of the tragedy that destroyed their lives, and especially not by relief workers “clad in bikinis and shorts”, further undermining the Muslims’ religion and beliefs.(47)

Koh Phi Phi is also an example of an area that suffered from inadequate response program. According to Jonathan Rigg, the community response in Koh Phi Phi was scattered and lacked unity. Initial government responses focused on clean up and the establishment of refugee camps, but did not address the rehabilitation of the overall community structures. In fact, the people of Koh Phi Phi have relied on tourist networking, backpackers, and donations from abroad in order to restore their community. Because of the nature of this relief, its sustainability is questionable as these resources are undoubtedly limited: as time passes and the tsunami awareness decreases, so will donations from abroad. As locals try to rationalize the damage caused by the tsunami, traditional beliefs merge with and at times scientific explanations, thus lessening the desire and drive of locals to rebuild their previous lifestyles, as many believe that the tsunami was a sign from god that peoples' lives before the tsunami were improper and deserved to be destroyed. With reconstruction has come an inevitable fear of the unknown and the uncontrollable. (see footnote #46)

The conflict currently raging in the South of Thailand illustrates the disaster that can result from the combination of loss of livelihood and environmental degradation. The 2004 tsunami heightened and worsened the already-existing conflict, resulting in much more than 1,000 deaths since mid-2004.(48) This conflict has many causes, the roots of which are economic and social discrimination against a minority Muslim population. Worsened by an inefficient response and environmental tragedy, the conflict has become chaotic, with the most important issues difficult to assess. Unless the RTG can learn to effectively communicate with the Muslims of the south, it is likely that this conflict and the resulting violence will continue for years to come.

“The conflict, argues the head of a local Islamic school, is like a plate of nasi kerabu, a Malay dish with many ingredients. Although Muslim separatist sentiment may contribute to the violence, so does heavy-handed repression by the security services, rivalry between the police and army, government neglect, political score-settling, drug-running, arms-smuggling, and so on. Anad Panyarachun, the head of the NRC and a former prime minister, agrees. He estimates that as many as half the incidents in the south are ordinary crimes mistaken for something more sinister."(49)

A variety of ingredients are mixed with rice and fish to create a heterogeneous combination of natural flavors. Similarly, the conflict in Thailand is the result of outside factors mixed with two populations, resulting in a multi-faceted conflict.

![]()

V. Related Information

and Sources

V. Related Information

and Sources

Tsunami and Aceh Conflict Resolution : The effect of the tsunami on Muslim separatists in Aceh, Indonesia.

Noah, the Flood, and Water as a Weapon : The historical presence and effect of floods and water disasters on various civilzations.

Hurricane Katrina and Violence: Violence in the wake of a natural disaster

Separatism in Mindanao, Philippines: Muslim Separatism and resulting violence

Amphetamine Trade Between Burma and Thailand: Highlights the border dispute between Burma and Thailand

Chalk, Peter. “Separatism and Southeast Asia: the Islamic Factor in Southern Thailand, Mindanao, and Aceh.” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, Vol. 24, 2001, pg. 241-269.

Che Man, Kadir. Muslim Separatism: The Moros of the Philippines and the Maylays of Southern Thailand. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Cheng, Tony. “Thai Troops Deployed to the South”. BBC News Online, January 3, 2005.

Greenhough, Beth, Tariq Jazeel, and Doreen Massey. “Introduction: Geographical Encounters with the Indian Ocean Tsunami”. The Geographical Journal, Vol 171, No. 4, December 2005, pg. 369-386.

Hardy, Roger. “The Riddle of the South" . BBC News Online, February 15, 2005.

Livelihood and Enivronment Recovery Assessment, UNDP/World Bank/FAO

Murphy, Column. “Friction on the Thai-Maylay Fault Line”. Far Eastern Economic Review, Vol. 168, No. 10, November 2005, pg. 21-25.

Rigg, Jonathan, Lisa Law, May Tan-Mullins, and Carl Grundy-Warr. “The Indian Ocean Tsunami: Socio-Economic Impacts on Thailand”. The Geographical Journal, Vol. 171, No. 4, December 2005, pg. 374-379.

“Thailand’s Restive South”. BBC News Online, July 15, 2005.

Tsunami Videos: real videos of tsunami action

United Nations Development Programme: Report one year after the tsunami

US Department of State Counterterrorism Office

United Nations Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission

![]()

© Erin Teeling, May 2006

![]()

1. Helen Lambourne, “Tsunami: Anatomy of a Disaster”, BBC News: http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-2-hi/science/nature/4381395.stm

2. “Tsunami Thailand: One Year Later, National Response and Contribution of International Partners”, United Nations Development Program, January 30, 2005: http://www.undp.or.th/documents/TsunamiTH_OneYearLater30jan.pdf, pg 13.

3. United Nations Development Programme, Thailand Tsunami. http://www.undp.or.th/focus/tsunami.html.

4. “Tsunami Thailand: One Year Later”, 15.

7. Paul Bishop, David Sanderson, Jim Hansom, and Niram Chaimanee, “Age Dating of Tsunami Deposits: Lessons from the 26 December 2004 Tsunami in Thailand”, The Geographical Journal, vol. 171, no. 4, December 2005: 381.

8. “Rapid Health Response, Assessment, and Surveillance After a Tsunami— Thailand, 2004-2005”, Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 293, No. 9, March 2, 2005: 1052.

9. UNICEF: Tsunami One Year Update, November 2005, http://www.unicef.org/tsunami/1year/overview/overview.html.

10. “Tsunami Thailand: One Year Later”, 24-25.

13. USAID, Indian Ocean Tsunami Early Warning System Press Conference Opening Remarks, Timothy T. Beans: http://www.usaid.gov/press/speeches/2005/sp050914_1.html

14. Nigel Clark, “Disaster and Generosity”, The Geographical Journal, Vol 17, No. 4, December 2005: 386.

15. Che W.K. Man, Muslim Separatism:the Moros of Southern Philippines and the Malays of Southern Thailand, Singapore, Oxford University Press (1990): 62.

20. Astri Suhrke, “Loyalists and Separatists: The Muslims in Southern Thailand”, Asian Survey vol. 17, no. 3 (March 1977): 241.

21. Syed Serajul Islam, “The Islamic Independence Movements in Patani of Thailand and Mindanao of the Philippines”, Asian Survey vol. 38, no. 5 (May 1998): 447.

29. Explanation of underground groups: Man, 98-100.

33. Raymond Scupin, “The Politics of Islamic Reform in Thailand”, Asian Survey vol. 20, no. 12 (December 1980): 1225-1226.

34. UNDP, “Tsunami Thailand: One Year Later, National Response and Contribution of International Partners”, December 2005, http://www.undp.or.th/documents/TsunamiTH_OneYearLater30jan.pdf: 27.

39. Astri Surhke, “Loyalists and Separatists: The Muslims in Southern Thailand,” Asian Survey, Vol. 17, No. 3 (March 1977): 241.

40. “Tsunami Thailand: One Year Later”: 38.

42. Tony Cheng, “Thai Troops Deployed to South”, BBC News Online, January 3, 2005: http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/asia-pacific/4142939.stm

43. “But at Last the Government is Listening”, The Economist, Vol. 375, No. 8429, June 4, 2005: pg 40.

45. Colleen Murphy, “Friction on the Thai-Malay Fault Line”, Far Eastern Economic Review, Vol. 168, No, 10, November 2005: 22.

46. Jonathan Rigg, Lisa Law, May Tan-Mullins, and Carl Grundy-Warr, “The Indian Ocean Tsunami: Geographical Commentaries One Year On; The Indian Ocean Tsunami: Socio-Economic Impacts on Thailand”, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 171, No. 4, December 2005: 377.

49. “But at Last the Government is Listening”, 40.