ICE Case Studies: July, 2011 |

Climate Change and the Turkana and Merille ConflictBy Jesse Creedy Powers |

I. Case Background |

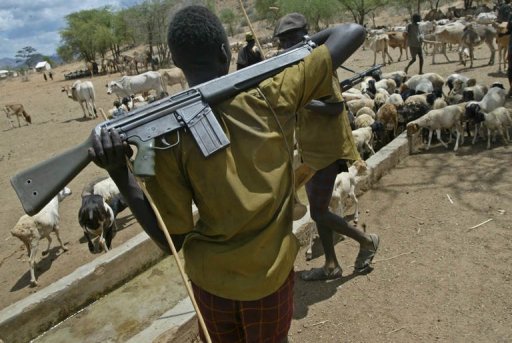

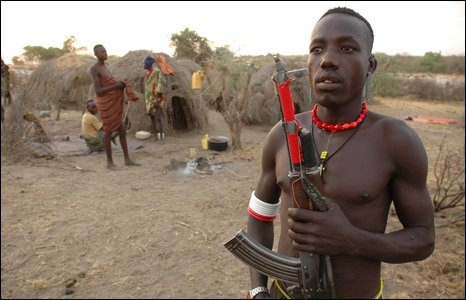

The Turkana tribe based out of northwest Kenya and the Merille (or Daasanach) living mainly in southern Ethiopia have historically clashed over ethnic differences and competition for resources. While the original cause of this conflict remains unknown (or forgotten), this conflict has been further exacerbated over the years by a number of environmental and human factors. Both of these groups number in the thousands and depend on cattle and agricultural practices as a means for their of survival. Human factors such as overpopulation, a high dependence on agriculture, and the wide availability of guns have caused the cultural tensions between these two groups to escalate over the years. Environmental factors have also led to widespread drought in the area causing scarce resources such as arable land and water to become scarcer. Documented conflicts between these groups started in the late 1950s with cattle raiding and killings over territorial claims and grazing grounds. The tensions between the Turkana and Merille people continue today and have been made more intense by factors such as drought and other socio-economic factors. Figure 1: The image on the right shows a Turkana man protecting a herd of cattle with an automatic weapon.

2. Location

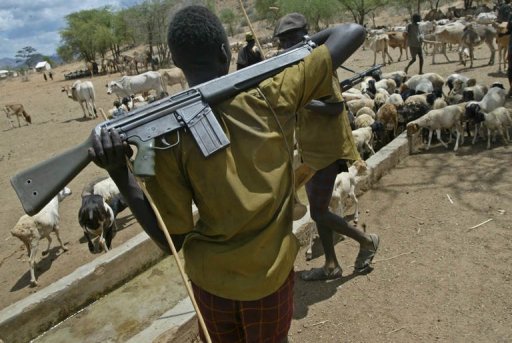

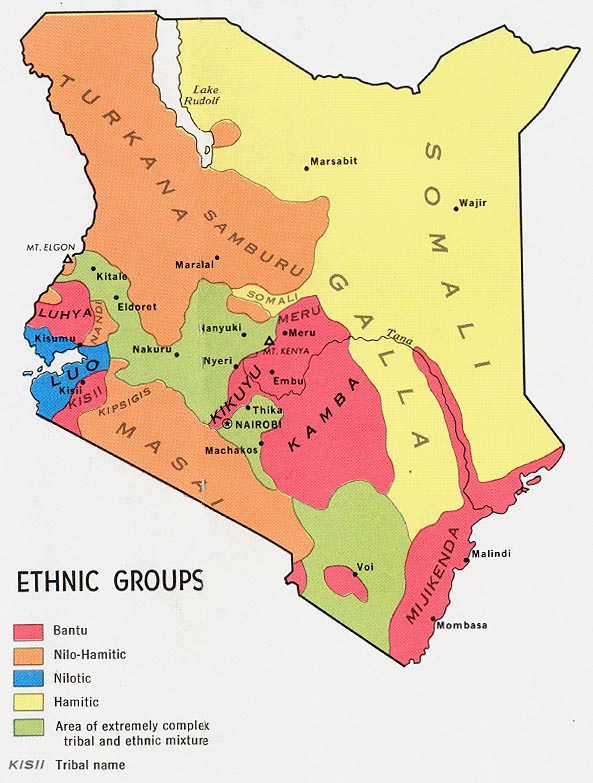

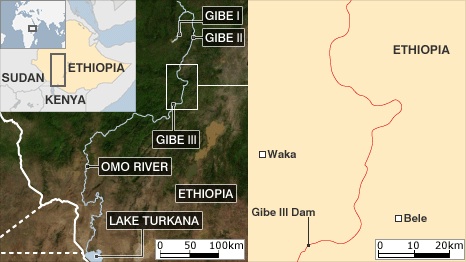

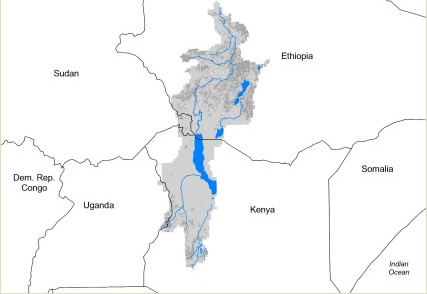

2. LocationThis conflict takes place in east Africa between the Ethiopian and Kenyan border as well as the disputed area known as the Ilemi triangle (bordering Ethiopia to the south, Kenya to the northwest, and Sudan; today the area is claimed by Sudan). [1] Figure 2 shows an over view of the area known as the horn of Africa and more specifically where this conflict takes place. This area consists of arid and semi-arid land where ground cover makes up less than 5% and vegetation is known to be very poor. [2] Rainfall in this area occurs in two peaks, one occurring between the months of March to May and the other between October to December. These two peaks in rainfall support the growing seasons in this area and are important for the growth of crops, natural vegetation, and livestock. The main water sources in this area are The Omo River that runs throughout Ethiopia and into Kenya, and Lake Turkana (referred to on the map as Lake Rudolf). Lake Turkana receives more than 90% of its water from the Omo River upstream. [3]

In 2009, these two countries ranked among some of the poorest countries in the world as measured by their per capita gross national income. Both Kenya and Ethiopia’s economies are highly dependent on their agricultural sectors that make up a large portion of both countries GDP. [4] Other issues that are prevalent to both of these countries are their high population growths, low literacy rates, low life expectancy, and the prevalence of HIV/AIDS.

Figure 2: This conflict takes place is on the Kenya and Ethiopian border around Lake Rudolf

The Turkana: The Turkana people have historically occupied the area in northwest Kenya located west of Lake Turkana. They began as nomadic shepards in Uganda but after suffering from a severe drought, migrated to the area in Kenya that they occupy today. Today the Turkana people are primarily cattle herders and number around 100,000. The area that the Turkana occupy is for the most part unsuitable for growing crops, thus explaining their high dependence on cattle. Most of their population lives in the Lake Turkana area in Kenya but others are known to live west of the Omo river in Ethiopia as well as the Ilemi triangle in Sudan. The survival of this tribe depends upon their ability to acquire land as well as their ability to raise and gain more livestock. While the Turkana people practice a mixed economy, about 80% of their livelihood is dependent on raising livestock. [7] The Turkana raise livestock such as sheep, camel, cattle and goats and their diet consists of the milk and meat that they acquire from these animals. This group is also known to trade with other ethnic groups in order to supplement their diets but these interactions often result in disputes over whether these trades are equitable or not. [8]

The Merille: While the majority of the Merille people live in southern Ethiopia, thousands of Merille also live in northwest Kenya along Lake Turkana. The Merille are also known as the Dassanach and number around 50,000 today. Merille livelihood depends on “pastoralism, flood-plain cultivation, and fishing in and around the Omo River.” The people depend on annual flooding of the Omo river in order to grow crops and for vegetation for their livestock to graze on. Crops are grown on the floodplain during the rainy seasons and are harvested during the dry season starting once in December and then again in February. Given their location close to the floodplains of the Omo River, in the past Merille people have been able to enjoy relatively stable supplies of crops and pasture. [9] However, during the past 50 years or so the Merille have suffered massive losses in their number of cattle, goats, and sheep as a result of land scarcity. The impact of these losses have caused larger numbers of Merille people to migrate to areas closer to the Omo river in an attempt to grow more crops as a way to survive. [10]

Figure 3: Different ethnic groups in Kenya; Figure 4: Different ethnic groups in Ethiopia (here the Merille are referred to as the Daasanach)

Both of these groups are historically nomadic given the geography of the land and the nature of their livelihoods. In order for both the Turkana and the Merille people to survive in these hot and semi-arid climates they must constantly migrate in search of better land and more water resources. This nomadic nature is what has caused these groups to clash in the past over territorial claims and water usage, and the reason that is fueling this conflict today. This environment also leads to cattle raiding from neighboring groups as a way for groups in this area to survive given the land's inability to support large populations. Added to this already historical ethnic tension is a lack of support from their governments as well as recent periods of drought that have caused land and water resources to become even scarcer. [11] Figure 5 to the left shows Merille people collecting water from permanent water sources and bringing it back to their established villages.

Both of these groups are historically nomadic given the geography of the land and the nature of their livelihoods. In order for both the Turkana and the Merille people to survive in these hot and semi-arid climates they must constantly migrate in search of better land and more water resources. This nomadic nature is what has caused these groups to clash in the past over territorial claims and water usage, and the reason that is fueling this conflict today. This environment also leads to cattle raiding from neighboring groups as a way for groups in this area to survive given the land's inability to support large populations. Added to this already historical ethnic tension is a lack of support from their governments as well as recent periods of drought that have caused land and water resources to become even scarcer. [11] Figure 5 to the left shows Merille people collecting water from permanent water sources and bringing it back to their established villages.

Records of the Merille and Turkana people occupying this region date back to the late 19th century. [12] The origin of this conflict remains unknown but has persisted over the years due to the same reasons that are fueling this conflict today: land, water resources, and territorial disputes. The abundance of these resources are what determine the amount of pasture, crop yields, milk and meat, and the availability of water that each of these tribes can use. In the past semi-nomadic ethnic groups in this area were known to co-exist peacefully however recent studies on conflict in this area show an increase in livestock raiding when climatic conditions increase. [13] An increase in ethnic conflicts in this area has been observed during times when droughts have been more persistent. This conclusion makes sense and gives an insight into why the ethnic tensions between the Turkana and Merille groups have persisted for more than six decades.

Droughts in this area result in a further decline on an already scarce supply of water and arable land. This decrease directly affects these two groups through decreasing their crop yields as well as their livestock numbers seeing as many cattle die from a lack of adequate grazing land or water. The only way for these groups to survive with their already bolstering population numbers are to migrate in search of better resources and relocate to areas closer to water sources. It is during these times of migration and drought that conflicts between these two groups most often arise. While the full list of recorded instances between these two groups are highlighted below, general triggers running throughout all of these include instances of: cattle raiding in order to replace cattle lost to climatic conditions, instances of revenge after one group initially attacks another, disputes of water holes and grazing land, and attacks after one group crosses the border into another group's territory. Ethnic tensions and cultural differences between these two groups also play a role in fueling this competition for scarce resources. While this cycle of migration, raiding, and revenge has been relatively constant throughout the history of this conflict, outside factors in the past few decades have introduced a new intensity to this already escalated conflict. Figure 6: A goat from a Turkana herd shows how the condition of the land makes it difficult to support large herds.

Droughts in this area result in a further decline on an already scarce supply of water and arable land. This decrease directly affects these two groups through decreasing their crop yields as well as their livestock numbers seeing as many cattle die from a lack of adequate grazing land or water. The only way for these groups to survive with their already bolstering population numbers are to migrate in search of better resources and relocate to areas closer to water sources. It is during these times of migration and drought that conflicts between these two groups most often arise. While the full list of recorded instances between these two groups are highlighted below, general triggers running throughout all of these include instances of: cattle raiding in order to replace cattle lost to climatic conditions, instances of revenge after one group initially attacks another, disputes of water holes and grazing land, and attacks after one group crosses the border into another group's territory. Ethnic tensions and cultural differences between these two groups also play a role in fueling this competition for scarce resources. While this cycle of migration, raiding, and revenge has been relatively constant throughout the history of this conflict, outside factors in the past few decades have introduced a new intensity to this already escalated conflict. Figure 6: A goat from a Turkana herd shows how the condition of the land makes it difficult to support large herds.

Duration: 60+ years

Decline in Water Resources: The availability of water plays a crucial role in this conflict because it is what determines the productivity of crops as well as the number of cattle that each group can support. As mentioned earlier, the main water sources in this area are Lake Turkana in northern Kenya and the Omo River that runs throughout southern Ethiopia. Water levels of each of these water sources are dependent on rainfall as well as human factors such as irrigation and the building of dams. Over the years a decline in water levels have added to this conflict by increasing the severity of available grazing and agricultural land, as well as causing increased migration.[20]

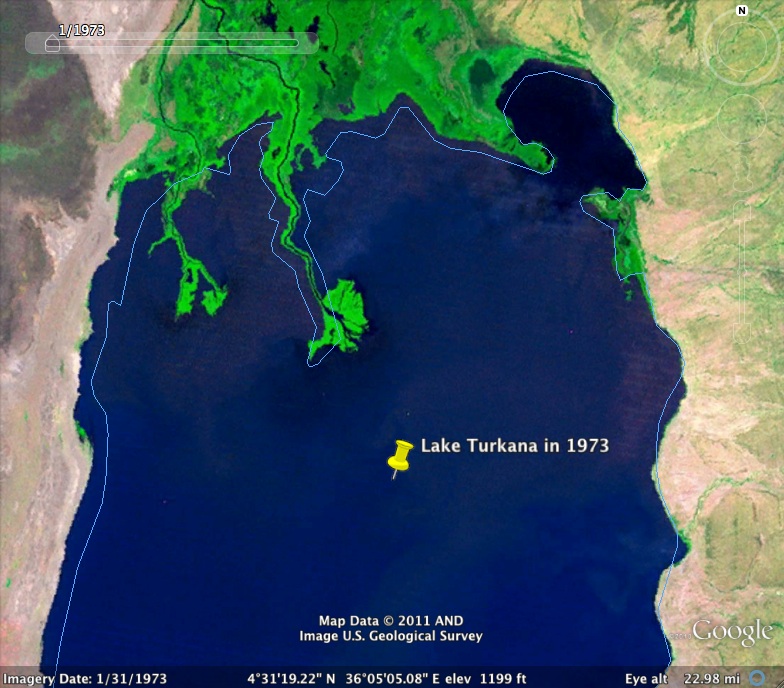

The Omo River begins in the north of Ethiopia and makes its way throughout Ethiopia before draining into Lake Turkana in Kenya. Lake Turkana receives about 90% of its water from the Omo River and over the years has seen drastic declines in its water levels. In the 1960s Lake Turkana was around 50-60 feet higher than it is today. A picture of this decline is featured below and shows how the water levels in Lake Turkana have receded from 1973 to 2005. The decline in water levels is connected to a decrease in rainfall in Ethiopia over the years along with hydroelectric dams and irrigation being built along the Omo River. [21]

The decline in water levels along Lake Turkana has had direct impacts on the conflict between the Turkana and Merille people. Traditionally the Omo River delta (where the Omo River drains into Lake Turkana) has served as border defining both the Merille and Turkana territory. The decline in water levels has caused a southward recession of Lake Turkana further into Kenyan territory. As the Merille people follow the receding water into Kenya, tensions between these two groups escalate as new territorial disputes arise. [22] Droughts also fuel the tension between these two groups by decreasing food supplies and increasing migration and cattle raids.

Figures 7 and 8: Both of the images above were taken from google earth and show the decline in Lake Turkana water levels from the year 1973 all the way up to 2005.

Gibe III Dam: The construction of the Gibe III Hydropower Dam began in 2006 as a way for Ethiopia to “diversify and develop its economy.” The government predicts that electricity generated from this dam could result in an addition of $407 million dollars annually by exporting this power elsewhere. [23] Ethiopian officials claim that the benefit from electricity generated from this dam will help to lift the annual per capital income of the country along with extending electricity to more than 70% of the population. Besides benefitting the economy, those in favor of this dam claim that the dam will also reduce Ethiopia’s dependency on wood for fuel and thus benefit the environment as well. [24]

Controversy surrounding the Gibe III dam stems from the negative environmental and social impacts that it is likely to create. Critics claim that in their rush to complete this project, Ethiopian officials violated international standards and failed to properly assess the impacts that could arise from the addition of this dam. Impacts of this dam include reducing water flow to all areas downstream, along with affecting more than 300,000 indigenous people who depend on the rivers annual floods for cultivation and grazing land. A reduction in water flow is also said to negatively affect fish populations along the river by impacting water inflow patterns. Those who oppose the Gibe III dam claim that the dam will negatively impact societies along the river by reducing river flow and threatening food security even further.

The reduction in water flow along the Omo river will have a direct affect on Lake Turkana and the people living in that area. Lake Turkana receives more than 90% of its water from the Omo River and supports more than 8 indigenous groups. The decrease in water levels will cause the lake to become increasingly more salty resulting in altering the ecosystem and wildlife in and around the lake. By filling the Gibe III dam, the water flow to Lake Turkana is said to be reduced by more than 50% along with resulting in a 23-33 foot drop in the depth of the lake. [25]

Figure 9: The image above shows where the Gibe dams are being built along the Omo River and the potential affects it can have on downstream water resources; Figure 10: An overview of water sources in this area, the main ones pertaining to this conflict are Lake Turkana and the Omo river.

Population increase: Along with an already noticeable decrease in available resources, another human factor fueling this conflict is the persistence of overpopulation in both of these countries. Between the years 2006-2009 both Kenya and Ethiopia have sustained an annual population growth rate of 2.6%. [26] In the Marsabit district in Kenya, the number of people living in this area has doubled over the past 30 years. [27] These two examples show how scarce resources in these two areas are becoming even scarcer as an increased number of people rely on land and water resources for their survival. With both of these groups already numbering in the thousands (50,000 Merille, 100,000 Turkana) large population growth rates aid to this conflict by adding to the overuse and scarcity of land and water resources.

Deforestation/Degradation of the land: Large population numbers along with a heavy reliance on land has resulted in the deforestation/degradation of land in both Ethiopia and Kenya. In Ethiopia it is estimated that the current loss of high forests number somewhere around 150,000-200,000 hectares annually. The main causes of deforestation in these areas are from clearing woodlands for fuel wood and construction materials. Degradation of the land usually results from over-grazing, the overuse from crop production, and fuel wood. Other factors that increase both deforestation and degradation include population, poverty, and the environment.

As a result of both deforestation and degradation soil erosion can increase while the resiliency of the land and nutrients in the soil can both decline. Soil erosion has negative impacts on crop productivity by removing the nutrient rich topsoil and reducing the soils ability to hold water. Erosion also removes soil depth thus removing soil for crops to grow in. If enough soil depth is removed, land in this area could eventually be reduced to dry land and eventually rock. Deforestation and degradation of the land results in a reduction in grazing land along with a decline in crop productivity and perhaps even crop failure. [28]

Deforestation and degradation of the land will result in fueling the conflict between the Turkana and Merille people. As the productivity of the land decreasing, cattle numbers along with crop output will both decline. As the number of cattle die from a lack of resources, cattle raiding will become more prevalent thus leading to more conflicts and instances of revenge. Crop productivity will also decline causing increased migration in search of better growing land, and leading to conflicts over land disputes and territorial claims.

The Availability of Guns: In the past, the conflict between the Merille and Turkana people were fought using traditional weapons such as spears and knives. Today in the Ilemi triangle located east of Lake Turkana, it is assumed that every male aged 17 and above is armed with an automatic weapon. [29] Guns were first introduced to the Merille people in 1898 by merchants and soldiers coming to Ethiopia from the north. Starting after World War I another influx of guns was introduced as the Ethiopian government supplied the Merille with guns in order for them to defend the Kenyan border. Since 1978 the Kenyan government has also been suspected of supplying guns to the Turkana people. Both of these groups have acquired guns over the years from their governments or local merchants in the area and have traditionally bartered goods and livestock in exchange for guns and bullets. The introduction of guns has heightened the ethnic tensions between these two groups and transformed what was once small-scale conflicts into larger battles. [30] Figure 11: The image on the left shows a Merille man holding a gun outside of his home.

The Role of Government: Both the Kenyan and Ethiopian governments have done little over the years to deflate the tensions between the Merille and Turkana people. During the 20th century both governments fueled these tensions by providing firearms to each side. After World War I and in the 1990s the Ethiopian government supplied the Merille people with automatic weapons, and at times allied with the Merille people against the Turkana people. During the early 20th century firearms were restricted in Kenya working to further escalated this tension by making the Turkana people more vulnerable to attacks. Besides arming these two groups with weapons, the neglect that both governments have had in addressing this conflict has also fueled this issue. [31]

The lack of development opportunities in the Ilemi triangle has resulted in the Kenyan and Ethiopian government paying little attention to this area. However it is here that a large number of conflicts between the Turkana and Merille people have occurred over grazing rights. The neglect of these two governments to address conflict in this area has resulted in an increasing number of outbreaks over grazing land in this area. While several peace meetings were held in 2006 between Ethiopian and Kenyan governments along with representatives from each tribe, the impacts of these meetings were short lived. Both governments have fueled tensions between these two groups over the years by providing a lack of regulatory aid along with arming each side with firearms. [32]

Climate Change: Climate in these two east African countries has been characterized over the years by increasing temperatures and decreasing precipitation rates. Since the 1960s temperatures in this area have risen about 2°F. Along with increasing temperatures, an increase in the severity and frequency of droughts in this area has also been observed. Today, “droughts have been occurring with the frequency and intensity not seen in recent memory…areas prone to drought every ten to eleven years are not experiencing drought every two to three.” Along with this increase in extreme events, the increase in temperatures is also aiding the decline of water levels in the Omo River and Lake Turkana by increasing the rate of evaporation. [33]

Climate Change: Climate in these two east African countries has been characterized over the years by increasing temperatures and decreasing precipitation rates. Since the 1960s temperatures in this area have risen about 2°F. Along with increasing temperatures, an increase in the severity and frequency of droughts in this area has also been observed. Today, “droughts have been occurring with the frequency and intensity not seen in recent memory…areas prone to drought every ten to eleven years are not experiencing drought every two to three.” Along with this increase in extreme events, the increase in temperatures is also aiding the decline of water levels in the Omo River and Lake Turkana by increasing the rate of evaporation. [33]

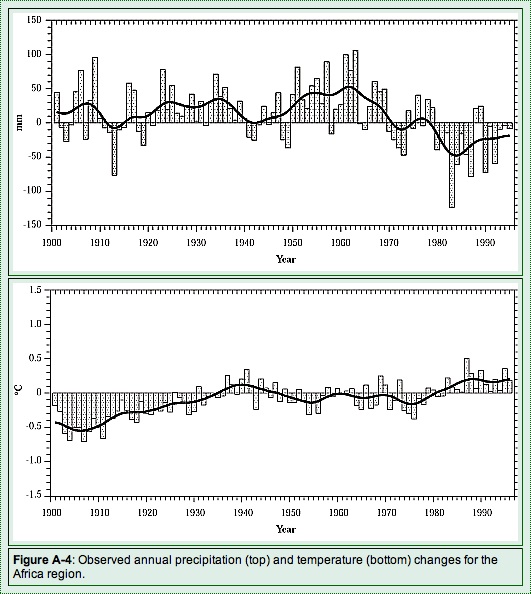

In 2011, ‘warmer-than-normal’ surface temperatures were seen in northern Kenya and southeastern Ethiopia worsening the affects of drought in these areas. This reduction in rainfall has added to the already increased stress on people living in these areas by, “rapidly depleting water, graze, and browse in pastoral areas” along with resulting in “crop failure in the marginal agricultural areas.” Along with the noticeable decline in available food sources, the decrease in arable land has resulted in the ”clustering of pastoralists around permanent water points.” [34] As mentioned earlier, conflicts between these two groups began to be recorded around the late 1950s. Figure 12 to the left shows how the increase in tempertatures around this time, along with a decrease in precipitation may have been the orginial cause of tension between these two groups . As temperatures increased and rainfall decreased, conflict may have started over the increasing scarcity of resources and claims to declining arable land and water sources. Climate change is fueling the conflict between the Turkana and Merille people by increasing the scarcity of resources in this area and increasing conflicts over land use and territory.

Figure 12: The graph on the top shows how precipitation has declined in this area while the bottom graph shows how temperatures have increased. Around the 1950s when conflict between these two groups began, temperatures were beginning to rise while precipitation around this same time started to decline. This observation suggests the importance that climate change has in fueling this issue.

This conflict is mainly internal occuring between the Turkana and Merille tribes who reside in Kenya and Ethiopia. Both governments from Ethiopia and Kenya have interjected over the years through providing and restricting guns to each group. Thier influence in the conflict is limited and they are for the most part uninvolved.

The level of conflict is related to resource access (water, land) and is heightened during times when these resources are scarce.

The total number of recorded fatalities between these two groups is around 430 deaths. The uncertainty in this number has to do with a lack of written evidence about this conflict throughout the years. This number was tallied from the recorded sources and may not include those conflicts which were not reported or where the number of those killed were not accurately accounted for.

The number of conlicts/fatalities per year is not consistent and depends mainly on climatic conditions. In years when droughts are prevalent, fatalities number somewhere around 100 deaths.

Low

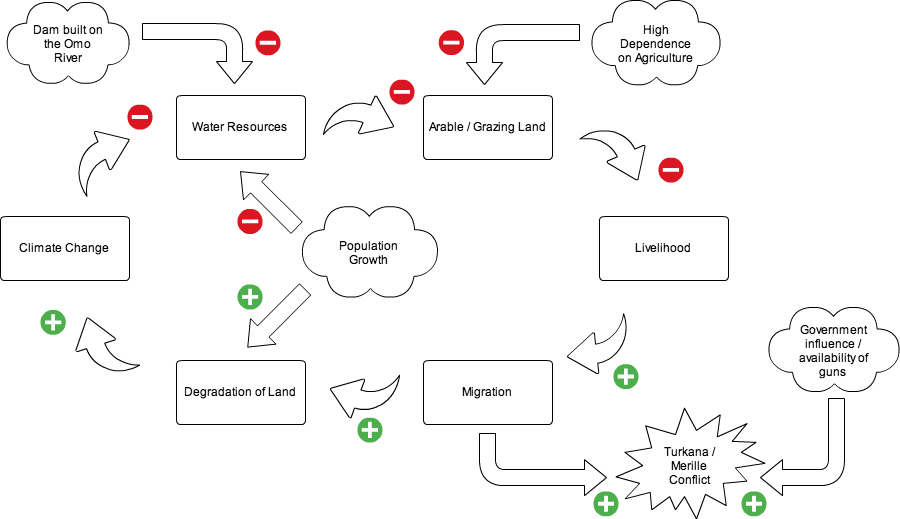

The main factors at play in the conflict between the Merille and Turkana people are the availability of land and water resources. Climate change and human impacts influence these resources through putting additional stress on their availability and aiding to the decline in both. As mentioned earlier, both Kenya and Ethiopia have increasing populations that add to the stress on arable/grazing land along with resulting in the overuse of available resources. Population, along with less rainfall due to climate change, and the reduction of water from the Gibe III dam, all place additional stress on the availability of water in this area and aid in the decline of its availability. The impact of less available water as a result of climate change and human impacts add to the decrease in arable land through increasing the frequency and intensity of droughts.

Both the Merille and Turkana people depend highly on land and water for their survival and a decline in arable land can lead to crop failure and less grazing land for cattle. The high dependency of these people on the land is also a result of a lack of alternative livelihoods. In Ethiopia, agriculture employs around 80% of the population, as well as making up around 23% of Kenya’s GDP in 2009. [35] A lack of alternatives for livelihood result in the high dependence on land and as a result of this dependence, results in the decline in arable land through over use.

Given their dependence on land for crops and cattle, a decline in arable land results in a decline in the livelihoods of both the Merille and Turkana people. In order to survive, both groups must migrate in search of better land and more reliable water resources. Here conflict ensues as government tensions, the addition of guns, and territorial claims cause these two ethnic groups to compete over livestock, land, and water usage. Migration fuels the degradation of land further by the continual cycle of occupying new land and then leaving when all available resources are used up. As a result of migration, deforestation and degradation are increased as new pieces of land are over used as a result of agriculture and cattle grazing. Degradation through overuse and migration can drive climate change further by destroying vegetation that could capture carbon dioxide (a greenhouse gas that increases climate change).

The cycle of competition, migration, and decline in resources, are what fuels the tensions between the Merille and Turkana people today. Additional human factors such as government influence and population growth increase the likelihood of this conflict by degrading land further and deepening already existing tensions. Today climate change is playing a more pivotal role in this historically ethnic conflict by increasing the scarcity of resources and aiding in migration. This conflict is likely to become more intense as the triggers for this conflict (crop failure, decrease in cattle, less water resources) occur more frequently.

This conflict is substate but has the potential for both Ethiopia and Kenya to become involved. If this conflict escalates to a point where more people are involved and there are increasing fatalities, the two states may need to intervene and send military assistance.

In progress. The role of declining resources and increasing demand in this issue will play an important role in determining whether this conflict will become worse in the future or not. Unless alternatives to cattle ranching or growing crops are offered to these two groups, the liklihood of this conflict becoming worse in the future is very high.

3. SUDAN: Civil War in the Sudan: Resources or Religion?, By D. Michelle Danke

29. NIGER: Fulani and Zarma Tribes Pushed into Fighting by Desertification, By Andrew H. Furber

151. TUAREG: The Tuareg in Mali and Niger, By Ann Hershkowitz

223. MALI-NOMAD: Tuarages and Climate Change, By Katie Kleury

246. ETHIOPIA-LAND-SWAP: Ethiopia and India Land Purchasing Program, By Feza Koprucu

Images:

1. http://ethiopiaforums.com/ethiopian-armed-men-kill-38-at-kenya-border

2. http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/africa.html

3. http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/kenya.html

4. Toru, Sagawa. “Automatic Rifles and Social Order amongst the Daasanach of Conflict Ridden East Africa.” Nomadic Peoples, Volume 14: Issue 1, Pg. 87. 2010. American University Library, 22 June 2011.

5. http://intercontinentalcry.org/peoples/dassanech/

6. http://www.burnabyblue.com/turkana

7. Google Earth, by Jesse Creedy Powers

8. Google Earth, by Jesse Creedy Powers

9. http://news.bbc.co. uk/2/hi/8582682.stm

10. Revenga, C., S. Murray, J. Abramovitz, and A. Hammond, 1998. Watersheds of the World: Ecological Value and Vulnerability. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. <http://earthtrends.wri.org/maps_spatial/maps_detail_static.php?map_select=308&theme=2>

11. Courtesy of BBC <http://www.nowpublic.com/environment/omo-river-basin-ethiopia-and-lake-turkana-kenya-photo-02>

12. http://www.ipcc.ch/ipccreports/sres/regional/index.php?idp=305

References:

[1] Haskins, Charles. “The Ilemi Triangle: A Forgotten Conflict.” SCCRR: Shalom Centre for Conflict Resolution and Reconcilation. 2010. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://shalomconflictcenter.org/conceptpaperarticles.html>

[2] Ruto Pkalya, Mohamud Adan, Isabella Masinde. “Indigenous Democracy: Traditional Conflict Resolution Mechanisms.” ITDG: Intermediate Technology Development Group. January 2004. Web (pdf). 22 June 2011.

[3] Leaky, Richard. “How Climate Change Affects East Africa.” WildlifeDirect. 3 July 2008. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://richardleakey.wildlifedirect.org/2008/07/03/how-climate-change-affects-east-africa/>

[4] “Climate Change in Africa: Key Facts and Findings.” IFPRI: International Food Policy Research Institute. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://www.ifpri.org/publication/climate-change-africa-key-facts-and-findings>

[5] “Ethiopia.” The World Bank Group. 2011. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://data.worldbank.org/country/ethiopia>

[6] “Kenya.” The World Bank Group. 2011. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://data.worldbank.org/country/kenya>

[7] Haskins, Charles. “The Ilemi Triangle: A Forgotten Conflict.” SCCRR: Shalom Centre for Conflict Resolution and Reconcilation. 2010. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://shalomconflictcenter.org/conceptpaperarticles.html>

[8] Ruto Pkalya, Mohamud Adan, Isabella Masinde. “Indigenous Democracy: Traditional Conflict Resolution Mechanisms.” ITDG: Intermediate Technology Development Group. January 2004. Web (pdf). 22 June 2011.

[9] Toru, Sagawa. “Automatic Rifles and Social Order amongst the Daasanach of Conflict Ridden East Africa.” Nomadic Peoples, Volume 14: Issue 1. 2010. American University Library, 22 June 2011.

[10] “Land scarcity drives a bout of ethnic violence in Kenya, Ethiopia.” The Christian Science Monitor: Africa Monitor. 10 May 2011. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Africa/Africa-Monitor/2011/0510/Land-scarcity-drives-a-bout-of-ethnic-violence-in-Kenya-Ethiopia?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+feeds%2Fworld+%28Christian+Science+Monitor+%7C+World%29>

[11] Haskins, Charles. “The Ilemi Triangle: A Forgotten Conflict.” SCCRR: Shalom Centre for Conflict Resolution and Reconcilation. 2010. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://shalomconflictcenter.org/conceptpaperarticles.html>

[12] Lamphear, John. “Aspects of Turkana Leadership during the Era of Primary Resistance.” The Journal of African History, Vol.17 No.2. 1976. Web. American University Library. 22 June 2011.

[13] Karen M. Witsenburg and Wario R. Adano. “Of Rain and Raids: Violent Livestock Raiding in Northern Kenya.” Civil Wars, Vol.11 Issue 4. 2009. Web. American University Library. 22 June 2011.

[14] “Kenya Battling Tribe on Border.” New York Times. 19 December 1957. Web American University Library. 22 June 2011.

[15] “32 Tribesmen Slain.” The Washington Post. 7 June 1963. Web. American University Library. 22 June 2011.

[16] Toru, Sagawa. “Automatic Rifles and Social Order amongst the Daasanach of Conflict Ridden East Africa.” Nomadic Peoples, Volume 14: Issue 1. 2010. American University Library, 22 June 2011.

[17] “Turkana-Merille Fighting: A Deadly Cycle in Kenya and Ethiopia.” Sahel Blog. 6 May 2011. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://sahelblog.wordpress.com/2011/05/06/turkana-merille-fighting-a-deadly-cycle-in-kenya-and-ethiopia/>

[18] “Elemi Triangle: A Theatre of Armed Cattle Rustling.” Practical Action. 2005. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://www.itcltd.com/peace6_elemi>

[19] “Turkana-Merille Fighting: A Deadly Cycle in Kenya and Ethiopia.” Sahel Blog. 6 May 2011. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://sahelblog.wordpress.com/2011/05/06/turkana-merille-fighting-a-deadly-cycle-in-kenya-and-ethiopia/>

[20] Leaky, Richard. “How Climate Change Affects East Africa.” WildlifeDirect. 3 July 2008. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://richardleakey.wildlifedirect.org/2008/07/03/how-climate-change-affects-east-africa/>

[21] Leaky, Richard. “How Climate Change Affects East Africa.” WildlifeDirect. 3 July 2008. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://richardleakey.wildlifedirect.org/2008/07/03/how-climate-change-affects-east-africa/>

[22] “Difficult Problems for Ethiopia, Kenya to Solve.” The Reporter. 21 May 2011. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://www.thereporterethiopia.com/Politics-and-Law/difficult-problems-for-ethiopia-kenya-to-solve.html>

[23] “Ethiopia’s Gibe III Dam: Sowing Hunger and Conflict.” International Rivers. May 2009. Web. 22 June 2011. < http://www.internationalrivers.org/node/4300>

[24] “Ethiopia’s Gibe II Dam: A Balanced Assessment.” Los Angeles Times. 4 June 2009. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://www.latimes.com/news/opinion/opinionla/la-oew-lautze4-2009jun04,0,2284769.story>

[25] “Ethiopia’s Gibe III Dam: Sowing Hunger and Conflict.” International Rivers. May 2009. Web. 22 June 2011. < http://www.internationalrivers.org/node/4300>

[26] “Population Growth.” The World Bank Group. 2011. 22 June 2011. <http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.GROW>

[27] Karen M. Witsenburg and Wario R. Adano. “Of Rain and Raids: Violent Livestock Raiding in Northern Kenya.” Civil Wars, Vol.11 Issue 4. 2009. Web. American University Library. 22 June 2011.

[28] Teketay, Demel. “Deforestation, Wood Famine, and Environmental Degradation in Highland Ecosystems: Urgent Need for Action.” Northeast African Studies 8.1. 2001. Web. American University Library. 22 June 2011.

[29] “Ethiopia’s Merille Militia Massacre 41 Turkanas.” Ethiopian History. Web. 22 June 2011. < http://www.ethiopianhistory.com/news2.php?story=201105050070>

[30] Toru, Sagawa. “Automatic Rifles and Social Order amongst the Daasanach of Conflict Ridden East Africa.” Nomadic Peoples, Volume 14: Issue 1. 2010. American University Library, 22 June 2011.

[31] Toru, Sagawa. “Automatic Rifles and Social Order amongst the Daasanach of Conflict Ridden East Africa.” Nomadic Peoples, Volume 14: Issue 1. 2010. American University Library, 22 June 2011.

[32] Haskins, Charles. “The Ilemi Triangle: A Forgotten Conflict.” SCCRR: Shalom Centre for Conflict Resolution and Reconcilation. 2010. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://shalomconflictcenter.org/conceptpaperarticles.html>

[33] “When The Water Ends: Africa’s Climate Conflicts.” Yale Environment 360. 2011. Web. 22 June 2011. < http://e360.yale.edu/feature/when_the_water_ends_africas_climate_conflicts/2331/>

[34] “East Africa Food Security Update 2011.” FEWS: Famine Early Warning System Network. 31 January 2011. Web. 27 June 2011. <http://www.fews.net/pages/region.aspx?gb=r2&l=en>

[35] “Climate Change in Africa: Key Facts and Findings.” IFPRI: International Food Policy Research Institute. Web. 22 June 2011. <http://www.ifpri.org/publication/climate-change-africa-key-facts-and-findings>