| ICE Case Studies

|

Melting Glaciers of Bolivia's Cordillera RealBrittany Stewart |

I.

Case Background |

Aymara Indigenous Man with Aymara Flag

The conflict is based on the issue of water supply. Indigenous people along with citizens of La Paz want compensationfor the affects climate change has had on their region. Scientists predict that the glacier the indigenous Aymara and citizens of La Paz depend on for water will disappear in 7-10 years. Issues of water scarcity and conflict have past roots in Bolivia's capital region of La Paz, given the Bolivian Water War in 2000.

The issue of water scarcity and climate change within the region has created exchanges between civil actors within Bolivia. Moreover, the role of climate change in the issue has Bolivians urging the involvement of international bodies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. As a whole the region is looking to various actors for retribution for climate change causing actions which increase the concern of water in the area.

The scientific community argues that the warming of the earth has caused major glaciers and ice sheets to melt at a more rapid rate than previously seen. Thus, there has been a rapid decrease in the global water supply, adversely affecting certain communities more than others.

Recently, the effects of large amounts of greenhouse gases within the atmosphere along with a rise in global temperature have been felt within the Cordillera Real region of Bolivia, the highest peaks of the Andes. Glaciers of the Andes were much larger than they presently are, and glaciers were also found in areas that no longer support permanent ice.

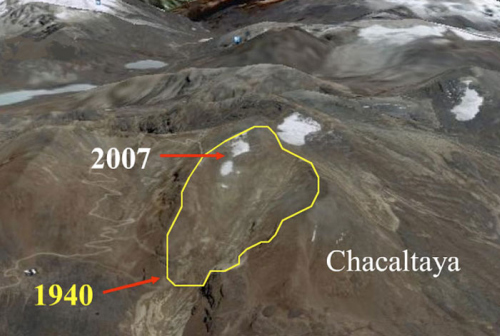

One of the most rapidly disappearing glaciers within the range is the Chacaltaya Glacier. Depicted in the figure below it is losing mass at an increased speed since the 1970s.

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chacaltaya Glacier Projected Melting |

Table of Mass Loss of Chacaltaya (Francou 2000) |

1940 Outline of Glacier |

|

| Fig 1. Glacier Distribution in a Section of Cordillera Real |

Glaciers within the region are dependent on the distribution and amount of precipitation. The southwestern part of the country does not receiveenough precipitation to maintain glaciers even on the highest peaks (Jordon 2008). As global temperatures increase due to greenhouse gases the amount of precipitation within the region continues to decrease. Without precipitation the likelihood of the glaciers being able to bounce back is slim. Tropical glaciers such as those located in the Cordillera Real only regenerate during the summer months when precipitation is the highest. Scientific data has shown that some glaciers could disappear in the next 10 years. Rates of melting increse significantly during warm phases of El Niño and decrease during cold phases of La Niña. Warm events have become more frequent and intense since the late 1970s in part due to global warming. Some glaciers within the Cordillera Real have lost some 40% of their total mass over the last 30 years (Francou 2000).

|

| Fig 2. Precipitation Distribution within the Region |

The issue of glacial melt is important to the region because the run-off from the Cordillera Real contributes to reservoirs that supply 1.5 million people in Bolivia's capital of La Paz as well as the city of El Alto (Jordon 2008). The melt water to replenish water aqueducts and reservoirs that supply the city's population with running water. In addition to supplying La Paz and El Alto, the run-off water is vital to indigenous groups that live near the mountains.

A group of indigenous people, called the Aymara, have been living within the Andean region of Bolivia for over 2,000 years. The Aymara people depend on melt water from the Illimani glacierin the Cordillera Reall for their water supply. The indigenous Aymara depend on the water not only for potable uses but also for agriculture. Without this melt water the people have no way of irrigation for agriculture thus affecting their food supply. The decreasing water supply is affecting indigenous crop yields and many are beginning to migrate. The decrease in water supply is forcing many men from villages along the mountains to go search for work elsewhere mainly in the city, leaving women and children to tend to the village's agriculture.

Fig 3. Hydrological Rates of Bolivian Glaciers Since 1992

The current issue of glacial melt water is not the first time in recent years that Bolivians and the indigenous have been concerned with access to water, a natural resource. Foreign corporations at the expense of the locals have long exploited Bolivia's natural resources including water access for foreign economic gain. For example, 10 years ago the Bolivian Water War occurred in the Cochabamba region when a San Francisco based company tried to privatize water in order to make a profit. The people within the Cochabama fought back and their water was kept as a public good. Bolivians living near and around the city protested through demonstration. Along with protests, the citizens were able to shut down the city's economy for four straight days by holding a general strike (Schultz 2000). During the demonstration police used force along with tear-gas in attempts to control the crowds.

Now in the case of climate change, Bolivians are demanding that the developed world take responsibilty for its actions, actions that affect Bolivian lives. The President of Bolivia, Evo Morales is becoming a more vocal participant in international climate change talks. Bolivia even recently hosted the People's World Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth. The meeting, proposed by Morales, brought together indigenous and civil society movements, scientists, activists, and government delegations to discuss different actions to appropriately taken the growing concern of climate change (Painter 2009).

Climate change is in progess. The increase in melt water begin in the 1970s and is still occurring today.

Conflict is likely to happen in the future as water becomes more scarce.

The concern for violence in the area is ever growing. There are currently no reported incidents of violence, but as water becomes increasingly difficult to receive tensions in the area will grow. Violence is also likely to occur as more indigenous people migrate from their rural comes and into cities. Social tensions among population groups will likely propel conflict.

The case study is occurring within the Cordillera Real Range of the Andes Mountains in South America. The issue is occurring within the national boundaries of Bolivia.

Actors include International Agencies such as the United Nations, Bolivian Government, Bolivian Citizens, Aymara Indigenous peoples.

Climate Change.

Rapid Glacial Melt.

Tropical, Mountainous.

Act Site: Global Climate Change (Historically the Global North, recently developing Global South Countries).

Harm Sites: Cordillera Real Region within Andes Region of Bolivia along with the cities of La Paz and El Alto.

Civil Conflict.

The possibility of conflicts occurring within Bolivia due to increased glacial melt and water issues can be classified as both international and civil conflicts. Foreign corporations at the expense of the locals have long exploited Bolivia’s natural resources including water access for foreign economic gain. In the past, a case of conflict occurred in response to the Bolivian Water War in 2000. The conflict was in reaction to foreign multi-national corporations trying to take control of Bolivian water supply within the region of Chococamba. The present issue of water scarcity is causing tension between Bolivian citizens and the indigenous Aymara that live closely together and therefore depend on the same glacial melt water supply.

In 2000, the Bolivian Water War occurred in the Cochabamba region when a San Francisco based company tried to privatize water in order to make a profit. The people within the Cochabamba fought back and their water was kept as a public good. Bolivians living near and around the city protested through demonstrations in downtown Cochabamba. Along with protests, the citizens were able to shut down the city’s economy for four straight days by holding a general strike (Schultz 2000). There were no reported deaths regarding the issue, however the demonstration represents tension in the region.

However, the source of the problem in this case is not human action as it directly relates to the water supply. A corporation is not trying to control a water source. Rather, the water is simply not there as a result of human action as it relates to global warming and climate change.

The issue of water accessibility will begin to highlight socio-economic disparities in Bolivia, especially between the wealthy of the capital La Paz and the indigenous Aymara.

Resource access to water.

Low.

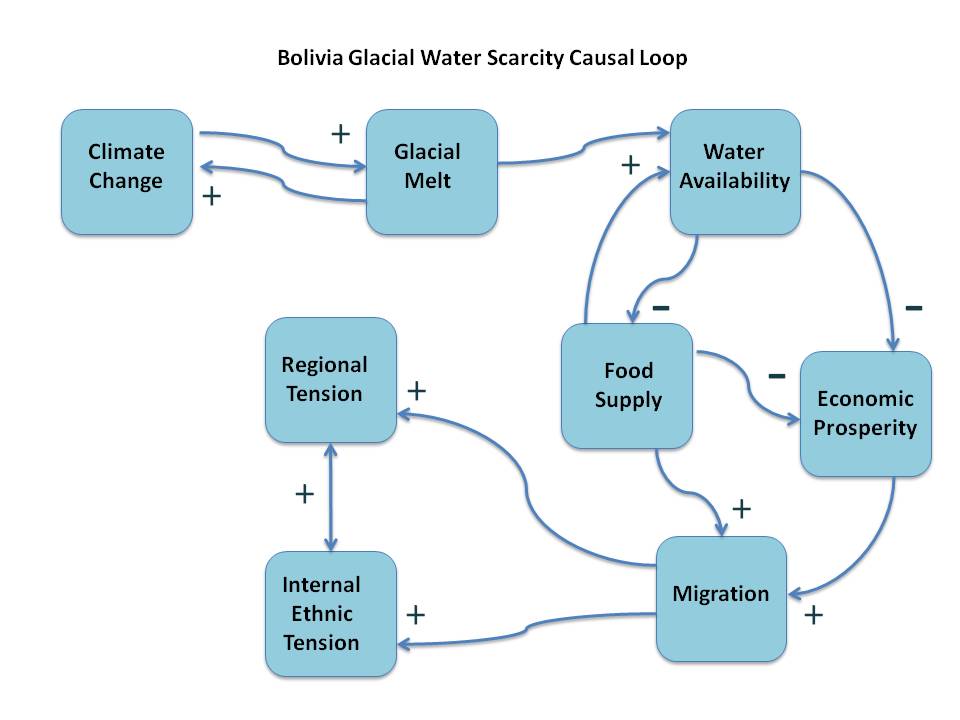

Climate Change creates a rise in temperature, which increase the rate at which glacial waters melt. The increase of melt water creates a rise in sea level as well as temperature creating more climate change. As glacial water melts more rapidly, the water supply begins to dry up more quickly creating a water scarcity. The lack of water creates a smaller food supply which forces people to migrate in search of food. A lack of an adequate food supply also creates a decrease in economic prosperity, which also forces the Aymara people to migrate. Migration, regardless of root causes, creates both internal tension within Boliva and regional tension between countries. Tension ultimately leads to various forms of conflict whether it is verbal disputes among people, legal disputes, or violent exchanges.

13. Level of Strategic Interest

State - Conflict over limited water resources within the region will be present on the Bolivian state level. Many groups will compete for water accessibility in order to maintain their livelihoods. High rates of migration within the region many affect neighboring states.

The issue and possibile outcomes are currently in progess with a high probability of continuing into the future.

In the past Bolivians have gained controlled over issues pertaining to water. Currently, there are no active violent disputes regarding water within the region. Instead, the government and citizens are searching for a way to manage their current predicament. Regardless the outcomes of disputes in the next few years Bolivians are set to lose a lot of control over their lives given the nature of the problem. Their lives are heavily influenced by the question of how much water will there be in 10 years and who ultimately gets what portion of a public natural resource.

Kashmir: Melting Glaciers, Boiling Conflicts by Samantha Hulkower

Conflict Over the Brahmaputra River Between China and India by Ryan Hodum

GREENLAND, Greenland and Climate Change by Kelly Hamrick

Enever, A. “Bolivian Glaciers Shrinking Fast”. BBC News World Edition (December 10, 2002). http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/2559633.stm

Francou, Bernard and Edson Ramirez, Bolivar Caceres and Javier Mendoza. "Glacier Evolution in the Tropical Andes during the Last Decades of the 20th Century: Chacaltaya, Bolivia, and Antizana, Ecuador". Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 49, no. 7 (Nov 2000). http://pinnacle.allenpress.com/doi/pdf/10.1579/0044-7447-29.7.416

Jordan, E. “Glaciers of South America—Glaciers of Bolivia”. Satellite Image Atlas of Glaciers of the World, United States Geological Survey, (March 18,2008). http://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/p1386i/bolivia/intro.html

Painter, J. “Bolivia’s Indians Feel the Heat”. BBC News (July 29, 2009). http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/8172981.stm

Shultz, J. "Bolivia's Water War Victory". Earth Island Journal. (September 22, 2000).

Shultz, J.. "Latin America Finds a Voice on Climate Change: With What Impact?" NACLA Report on the Americas 43, no. 4 (July 1, 2010): 5-6. http://www.proquest.com.proxyau.wrlc.org/.

Figures

TIMELAPSE 1940 - 2007 http://lastdaysoftheincas.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/andes-gallery-timelapse-700.jpg

Percent Loss Table http://pinnacle.allenpress.com/doi/pdf/10.1579/0044-7447-29.7.416

US Geological Survey http://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/p1386i/bolivia/5fig4.gif , http://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/p1386i/bolivia/intro.html

[December 13th, 2010]