|

ICE Case Studies |

Violence in Southern Ethiopia: by Ann Hershkowitz |

I. Case

Background |

![]()

Ethiopia has suffered recurrent droughts throughout the last half of the 20th century, which are often accompanied by widespread famine. The droughts exacerbate the degradation of the semi-arid lands in the south, which are becoming less able to support either farming or pastoralist activities. In addition, government support of large-scale farming in recent years has left many small farmers, and especially pastoralists, without access to the better-quality land. As a result, many pastoralists like the Borana are no longer able to support as many cattle, and must work even harder to ensure the survival of these smaller herds. The Borana resent the large farmers, as well as the government officials who have supported them. As one Borana man said, “They hate us and are trying to destroy our way of life.” Tensions between large farmers and Borana people erupted into violence in August 2004.

The Borana (also spelled Borena) are a semi-nomadic pastoralist people who live in southern Ethiopia in the region of the same name. The land is mostly savanna, and suffers from frequent droughts. The Borana and their ancestors have lived here for hundreds of years, and have traditionally been pastoralists. They keep mostly cattle, but some goats, sheep, and increasingly camels, are kept as well. They have developed an effective system for managing watering holes and wells to ensure the sustainable use of water in this dry region.1

Map showing the Borana region in Ethiopia. © IRINnews.org

Map showing the Borana region in Ethiopia. © IRINnews.org

However, the increasing desertification of their land has severely hurt traditional pastoralist practices in southern Ethiopia. The growing population means that it is harder for pastoralists to spread out grazing by moving to unused land; as a result, overgrazing has become a problem, and contributes to the degradation of the land. In addition, government rural development policies of the last decades have supported large-scale agriculture for growing cash crops, further decreasing the amount of available land for grazing herds. The irrigation systems needed to support crops may also be straining the water resources of the region, worsening drought conditions when they occur.

The Borana deeply resent the government’s support for the large farmers. They believe many of the large farmers are bribing government officials for access to the best land, and for favorable loans to support their agro-businesses. The large farms have started fencing their fields to prevent stray grazing on their land; this has had the added effect of preventing the Borana from moving their herds to certain areas, often to cutting off access to traditional watering holes. The increased difficulty of moving herds, combined with the steady desertification of the land, has made life for these pastoralists much harder. Many have abandoned the traditional lifestyle and immigrated to urban areas in the hope of finding work. Others have taken up small-scale farming, though they also have trouble accessing quality land. Borana farmers resent the large-scale farmers for what they see as the latter group’s unfair advantages, achieved through corrupt means. The remaining Borana pastoralists are growing despondent over the increased hardships to their way of life, and see government policies for rural areas as an attempt to destroy their traditional lifestyle.

The tensions between Borana pastoralists and large-scale farmers came to a head in August 2004. On the 8th of that month, two Borana boys tending to their family’s cattle found a weak spot in the fencing around a maize farm, and were able to move a section of fence to allow their cattle access to the field. They were taking a shortcut to a watering hole, and although they did not allow the cattle to stop to graze on the crop, some damage did occur. When the farm manager saw them on their return from the watering hole he chased them, catching one of the boys and severely beating him. He also allegedly told the boy he would kill the boy’s family if he caught cattle on the farm again. Furthermore, he shot and killed one of the cows, and shot at several others.

When the news reached the family of the boy they were outraged. Not only had one of their boys been hurt, but a cow was killed. Cattle are the Borana’s main source of income, and with reduced herd sizes in recent years, the loss of even one cow is a serious economic shock. Ten teenage and adult male members of the family went to the farm that night to demand payment for the lost cow. The farm manager refused, and threatened them with a shotgun. A struggle broke out, and one of the Borana wrestled the gun from the farm manager, who began running away through the fields. The Borana gave chase. In the darkness the farm manager tripped on a rock and hit his head; he died the next morning from the injury.

The death of the farm manager, though not directly caused by the Borana men, incensed the other large-scale farmers, and some of the smaller farmers as well. Two days later they formed a militia and attacked a Borana settlement, killing about 15 men. The Borana retaliated by burning the fencing around the farm of one of the militia members, destroying half the crop in the process. One farm worker was killed trying to put out the fire.

The Borana mostly left village area after this, fearing future attacks from farmers. However, they have been attacked in several other areas, and sometime in the autumn months of 2004 a group of young Borana men organized a militant group to protect their families and respond to any attacks. Farmers claim this group has killed over 40 farmers, though Human Rights Watch believes the number is closer to 20. The Borana, on the other hand, claim over 100 of their people have been killed; again, Human Rights Watch believes the number is closer to 60. The violence, while sporadic, has not stopped. Both sides blame the other, and show no signs of willingness to negotiate or otherwise bring the conflict to an end.

The violent conflict began in August 2004 and is still ongoing.

Continent: Africa

Region: East Africa

Country: Ethiopia

Borana and non-Borana farmers in Ethiopia

Environmental Problem Type: Source, Habitat Loss

Dry. The Borana region in southern Ethiopia is a semi-arid plain. The FAO reports that over 80% of land in Ethiopia is dryland. 2

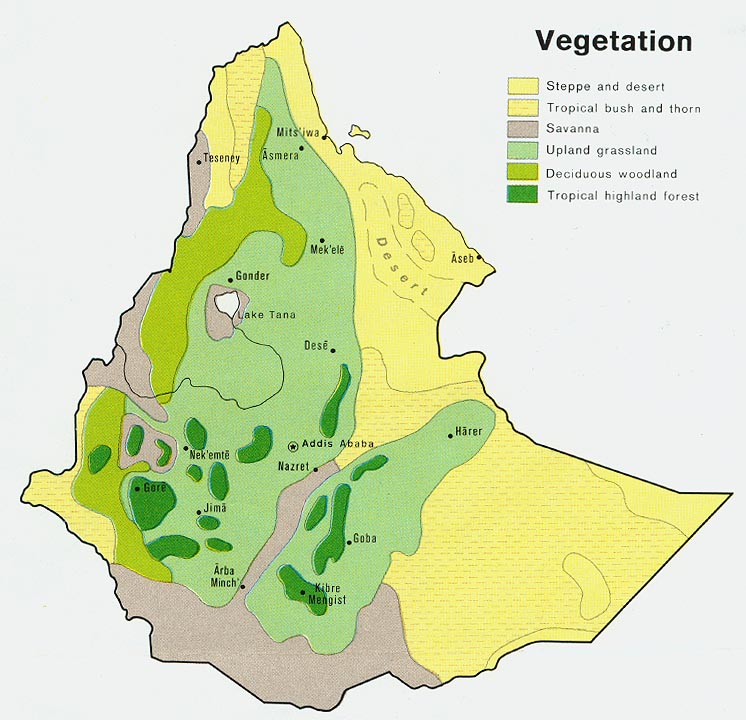

This map shows the different types of vegetation in Ethiopia. The Borana

region is composed of savanna and upland grassland.

Act Site: Ethiopia

Harm Site: Ethiopia

![]()

Civil. The greater availability of guns in Ethiopia has worsened the violence. Many analysts credit the war with Somalia in the mid 1970s for bringing more guns into the country, as well as the border war with Eritrea in the 1990s.

Intrastate, Low

The exact number of deaths is not known, but probably number between 70 and 100 in the last year.

![]()

Direct. Tension over the smaller amount of usable land, especially the fencing off of agricultural land that decreased access to rivers and other water sources, was the source of the conflict. The slow but steady degradation of the land, combined with a rising population, means that more people are competing for less usable land. In addition, government land policies that support agricultural development are seen as biased by the Borana. Many Borana leaders have espoused the position that large farmers are bribing government officials to support agricultural policies that threaten the pastoralist way of life.

Sub-state.

In Progress. Sporadic fighting continues today, with no sign of a ceasefire in the immediate future.

![]()

It is clear from this case that the environment does play a role, often an important one, in violent conflicts. However, it is certainly not the sole reason for conflicts; economic and social factors are also important. The environment is often closely related to economics; for example, in this case, land degradation caused non-degraded land to become an increasingly scarce – and thus valuable – resource. Those who control access to the resource (land) have the advantage and may thrive; those who cannot gain access (for either financial or socio-cultural reasons) usually suffer a loss of livelihood and a decrease in their quality of life. If they can no longer earn a living as pastoralists or farmers, many find they must change professions. They may leave rural areas for cities, which are becoming overcrowded and have high unemployment rates. Urban living in developing countries presents new socio-economic problems for rural immigrants, and usually does not increase quality of life (especially for those people who are upset at the loss of rural lifestyle and culture).

There are several options to help prevent violent conflict in similar cases. From an environmental standpoint, the UN has had several successful programs that work to slow or reverse desertification of semi-arid lands (see UNEP Programme on Success Stories in Land Degradation/ Desertification Control). Sound land management, including planting of trees and shrubs in degraded areas, is extremely helpful.

Government policies that encourage nomadic pastoralists to settle are not appropriate. In addition to often creating ill-feelings toward the government on the part of pastoralists, these policies do not solve the problem of desertification. If land continues to become less productive and/or unusable, competition for quality land will continue, whether for use in growing crops or raising livestock. Instead, government support for sustainable farming and pastoralist practices is necessary.

Finally, a clear and fair grievance process for handling rural land disputes – before they become violent -- would also be helpful. While many groups have effective dispute resolution methods, when the argument is between members of different groups with different systems, these systems may no longer be appropriate.3 If the government set up a new system, it would require an unbiased mediator that was trusted by both sides. Whether or not this is a realistic possibility depends largely on several factors, including:

![]()

Nine cases came up with a score of 50% or higher, using the following criteria:

Continent |

Africa |

Region |

East Africa |

Country |

Ethiopia |

Habitat |

Dry |

Environmental Problem |

General habitat loss |

Scope |

Substate and NGO |

Trigger |

Other access issues |

Type |

Civil |

Outcome |

In progress |

Level of Conflict |

Low |

Beginning year |

Modern (1900-present) |

Beginning year |

Not available/applicable |

The results, with percentage of match, were as follows:

| 67% | No.27 Niger |

| 67% | No.31 Poach |

| 50% | No.97 Landmine |

| 50% | No.24 Sahara |

| 50% | No.23 Rwanda |

| 50% | No.46 Kikuyu |

| 50% | No.3 Sudan |

| 50% | No.13 Chiapas |

| 50% | No.64 Ogonioil |

There were 15 cases ranging from an 88% match to a 52% match on the ICE expert matching system, using this criteria:

Field |

Value |

Weight |

Continent |

Africa |

2 |

Region |

East Africa |

1 |

Country |

Ethiopia |

1 |

Habitat |

Dry |

6 |

Environmental Problem |

General habitat loss |

4 |

Scope |

Substate and NGO |

5 |

Trigger |

Other access issues |

1 |

Type |

Civil |

3 |

Outcome |

In progress |

1 |

Level of Conflict |

Low |

1 |

Beginning year |

Modern (1900-present) |

1 |

Beginning year |

Not available/applicable |

1 |

The results, with percentage of match, were as follows:

| 85% | No.27 Niger |

| 74% | No.3 Sudan |

| 74% | No.31 Poach |

| 67% | No.97 Landmine |

| 67% | No.24 Sahara |

| 63% | No.30 Angola |

| 59% | No.60 Marsh |

| 59% | No.83 Sudan-sanctions |

| 59% | No.103 Abumusa |

| 59% | No.23 Rwanda |

| 56% | No.65 Somwaste |

| 56% | No.2 Eritrea |

| 56% | No.13 Chiapas |

| 52% | No.41 Grainwar |

| 52% | No.51 Chiledam |

For the Relevance search, a total of 20 cases had a match of 50% or better, based on the following search criteria:

The top 6 results, with percentage of match of 60% or higher, were as follows:

| 65% | No.27 Niger |

| 65% | No.46 Kikuyu |

| 61% | No.24 Sahara |

| 61% | No.64 Ogonioil |

| 61% | No.43 Biafra |

| 61% | No.30 Angola |

For the Decision Outcome search, over 50 cases had a 50% or higher match, based on the following criteria:

The top seven results, all with an 84% match, were as follows:

| 84% | No.80 Congo |

| 84% | No.54 Haitidef |

| 84% | No.6 Jordan |

| 84% | No.68 Jayamine |

| 84% | No.42 Brazmigr |

| 84% | No.101 Papua |

| 84% | No.53 Cauvery |

The Niger case was the top result for both basic results searches and the relevance search, with 67%, 85% and 65% matches respectively. However, it was not featured in the outcome search.

None of the cases appeared on all four lists. As stated, Niger appeared on three of the four, as did Sahara. Sudan, Poach, Landmine, Angola, Rwanda, Chiapas, Kikuyu, and Ogonioil all were found in the results of two searches. Marsh, Sudan-sanctions, Abumusa, Somwaste, Eritrea, Grainwar, Chiledam, Biafra, Cauvery, Haitidef, Jayamine, Papua, Congo, Jordan, Brazmigr, and Papua appeared in only one search.

However, because of the relatively low degree of relevance for both basic searches and the seeming irrelevance of the relevance and reliability results, I determined the top three similar cases based on the following criteria, listed in order of importance:

The Kikuyu case was the most similar, as it fulfilled all of the above. Although the rebel groups were not in conflict with the government, the government did have seem to choose sides and was involved in the forced migration of Kikuyu refugees. Interestingly in this case, the government sided with the pastoralists.

The Niger case was the second-most similar, as it fulfilled numbers 1, 2, and 4 above.

Following closely from the Niger cases, the Sudan case was the third-most similar. It fulfilled all of the criteria except the second – the livelihood tensions were between small and large-scale farmers, not farmers and pastoralists. I ranked it closely to, but below, the Niger case because I felt the livelihood tensions were more important in determining similarities with the Borana case than government rural policies.

1.) Kate Eshelby, “Pastoralists under Pressure,” Geographical 77 (July 2005). Accessed online from Academic Search Premier 29 July 2005.

2.) From the Food and Agriculture Organization webpage, available at http://www.fao.org/desertification/default.asp?lang=en

3.) For instance, the Borana have a sophisticated system for solving disputes within their own community. See Eshelby, 2005.

Vegetation map of Ethiopia from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, University of Texas at Austin.

Map showing the Borana zone in Ethiopia from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, available at http://www.irinnews.org/webspecials/drought/galleryindex.asp.

Desalegn Chemeda Edossa, Mukand Singh Babel, Ashim Das Gupta and Seleshi Bekele Awulachew. “ Indigenous systems of conflict resolution in Oromia, Ethiopia.” International workshop on ‘African Water Laws: Plural Legislative Frameworks for Rural Water Management in Africa’, 26-28 January 2005, Johannesburg, South Africa. Available from http://www.nri.org/waterlaw/AWLworkshop/DESALEGN-CE.pdf.

Eshelby, Kate. “Pastoralists under pressure.” Geographical 77 (July 2005): p42.

![]()

[July 2005]