I. CASE

BACKGROUND

I. CASE

BACKGROUNDSome scholars argue that extermination of the buffalo was an official policy of the US government in order to achieve extermination of the Native Americans, particularly those living in the Western Plains. We will examine this theory, as well as the history of the settlement of the "American West".

Virtually every part of the United States except the Eastern Seabord has been "the West" at some point in American history, linked in popular imagination with the last frontier of American settlement. But it is especially that vast stretch of plains, mountains, and the desert west of the Mississippi that has loomed so large in American folklore, a region of cowboys, Indians, covered wagons, outlaws, prospectors, and a whole society operating outside the law.

As with the other sections of the United States, regional boundaries are somewhat imprecise. The West of the cowboy and cattle drive covered many non-Western states, including Kansas and Nebraska. Much of the West's fiercest Indian fighting took place in the Dakotas, both of which are now considered to be part of the Middle West.

Much of the West became part of the United States through the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, the Southwest however, was a Mexican possession until 1848. The Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-1806 established much of what would become the Oregon Trail and thereby facilitated settlement of the Pacific Northwest, an area soon known for its richness in furs, timber, and salmon. The discovery of gold in California in 1848 brought a burst of migration to the West Coast and led to California's admission to the Union in 1850, barely two years after it had been ceded from Mexico.

The first British settlers in the New World stayed close to the Atlantic, their lifeline to needed supplies from England. By the 1630s, however, Massachusetts Bay colonists were pushing into the Connecticut River valley. Resistance from the French and the Indians slowed the movement westward, yet by the 1750s northern American colonists had occupied most of New England.

The British Proclamation of 1763 ordered a halt to the westward movement at the Appalachians, but the decree was widely disregarded. Settlers moved into Ohio, Tennessee, and Kentucky. After the American Revolution, a flood of people crossed the mountains into the fertile lands between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River. By 1810 Ohio, Tennessee, and Kentucky had been transformed from wilderness into a region of farms and towns.

Despite those decades of continuous westward pushing of the frontier line, it was not until the conclusion of the War of 1812 that the westward movement became a significant outpouring of people across the continent. By 1830, the Old Northwest and Old Southwest-areas scarcely populated before the war--were settled with enough people to warrant the admission of Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, Alabama, and Mississippi as states into the Union.

During the 1830s and ‘40s, the flood of pioneers poured unceasingly westward. Michigan, Arkansas, Wisconsin, and Iowa received most of them. A number of families even went as far as the Pacific coast, taking the Oregon Trail to areas in the Pacific Northwest. Between the gold rush and the Civil War, Americans in growing numbers filled the Mississippi River valley, Texas, the southwest territories, and the new states of Kansas and Nebraska. During the war, gold and silver discoveries drew prospectors--and later settlers--into Oregon, Colorado, Nevada, Idaho, and Montana.

By 1870, only portions of the Great Plains could be truly called unsettled by the descendants of the first colonists.

For many decades, most Americans knew of the Great Plains simply as the Great American Desert, an inhospitable area of poor soil, little water, "hostile" Indians, and general inaccessibility. But the years following the American Civil War changed that conception. In 1862 the Homestead Act was passed by Congress; in 1869 the first transcontinental railroad was completed; and in 1873 barbed wire fencing was introduced. Coupled with improvements in dry farming and irrigation and the confinement of American Indians to reservations, after much brutal warfare, the Great American Desert grew steadily in population.

By late 1880, with the decline of the range-cattle industry, settlers moved in and fenced the Great Plains into family farms. That settlement--and the wild rush of pioneers into the Oklahoma Indian Territory--constituted the last chapter of the westward movement. By the early 1890s, a frontier had ceased to exist within the 48 continental states.

What came to be known as the Indian Territory was originally all of that part of the United States west of the Mississippi, and not within the States of Missouri and Louisiana, or the Territory of Arkansas. Never an organized territory, it was soon restricted to the present state of Oklahoma. The Choctaw, Creek, Seminole, Cherokee, and Chickasaw tribes were forcibly moved to this area between 1830 and 1843, and an act of June 30, 1834, set aside the land as Indian country which later came to be known as Indian Territory.

In 1866, the western half of Indian Territory was ceded to the United States, which opened part of it to white settlers in 1889. This portion became the Territory of Oklahoma in 1890 and eventually encompassed the lands ceded in 1866. The two territories were united and admitted to the Union as the state of Oklahoma in 1907.

The North American Plains Indians were essentially big-game hunters, the buffalo being a primary source of food and material which was used for clothing, shelter, tools and religious icons. The peoples of the Plains are typically designated by the languages they speak. It should be noted, however, that in some cases the designation covers several completely autonomous political divisions. For example, the designation of Dakota, covers several different (and autonomous) political divisions. The northern and southern divisions of the Cheyenne retained their unity as a tribe, while the Pawnee on the other hand comprised at least four independent groups. Many of the nations or tribes from the Plains migrated from the prairies and woodlands of the east. Six distinct language families or stocks were represented in the Plains area, although none was confined to it. Sign language provided a common, if limited means of communication among tribes speaking different languages. This was a system of fixed hand and finger positions symbolized ideas, the meanings of which were known to the majority of the tribes of the area.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830, was the first major legislative departure from the US policy of respecting the legal and political rights of the American Indians. The act authorized the president to grant Indian nations unsettled western prairie land in exchange for their desirable territories within state borders from which the tribes would be removed. Although the bill provided only for negotiation with tribes east of the Mississippi on the basis of payment of their lands, trouble arose when the United States resorted to force to gain the Indians' compliance with its demand that they accept the land exchange and move west.

A number of northern tribes were peacefully resettled in western lands not considered useful to the white population. The problem lay in the Southeast, where members of what were known as the Five Civilized Tribes (Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole, Cherokee, and Creek) refused to trade their cultivated farms for the promise of strange land in Indian Territory with a supposed permanent title to that land. Many of these Indians had homes, representative government, children in missionary schools and trades other than farming. Some 100,000 tribespeople were forced to march westward under US military coercion in the 1830s. Up to 25 percent of the Indians, many in manacles (shackles for the hands) perished on the way. The trek of the Cherokee in 1838-1839 became known as the Trail of Tears. Also reluctant to leave their lands were the Florida Indians, who fought resettlement for seven years (1835-42) in the second of the Seminole Wars.

The frontier began to be aggressively pushed westward in the years that followed, upsetting the "guaranteed" titles of the displaced tribes and further reducing their relocated holdings.

By the 1860s, American Indian policy included several key principles, such as the treaty system with its recognition of the "red man's" rights to land, regulation of trade through various Indian Trade and Intercourse Acts, and promotion of civilization and education. Control of Indian affairs had originally been the task of the War Department. The Bureau of Indian Affairs, created in 1824, and the office of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, which followed were still responsible to the Secretary of War. In 1849, however, the Indian Bureau was transferred to the newly created Department of the Interior, which meant that the Army would take over when bloodshed occurred. (General Pope and U.S. Indian Policy, p. 32)

E. US POLICY TO EXTERMINATE THE BUFFALO

E. US POLICY TO EXTERMINATE THE BUFFALOSome scholars suggest that in order to make migration to the west easier, the US government, through the Army, adopted a policy to exterminate the buffalo. Extermination of the buffalo would inevitably mean the demise of the Indians who so relied on them for almost every aspect of their existence.

"Although the army was plagued by strategic failures, the near extermination of the American bison during the 1870s helped to mask the military's poor performance. By stripping many Indians of their available resources, the slaughter of the buffalo severely reduced the Indians' capacity to continue an armed struggle against the United States. The military's role in this matter is difficult to asses. Sheridan and Sherman recognized that eliminating the buffalo severely reduced the Indians' capacity to continue an armed struggle against the United States. The editors of the Army and Navy Journal supported the proposition, comparing such an effort with Civil War campaigns against Confederate supplies and food sources. Forts provided de facto support for hunters, who used the civilian services often found near army bases. Officers and enlisted personnel also killed buffalo for food and sport, though the impact of their hunts was minute when compared to the organized efforts of the professionals." (The Military and United States Indian Policy, p. 171) "In 1874, Secretary of the Interior Delano testified before Congress, "The buffalo are disappearing rapidly, but not faster than I desire. I regard the destruction of such game as Indians subsist upon as facilitating the policy of the Government, of destroying their hunting habits, coercing them on reservations, and compelling them to begin to adopt the habits of civilization." (The Military and United States Indian Policy, p. 171) Two years later, reporter John F. Finerty wrote that the government's Indian allies "killed the animals in sheer wantonness, and when reproached by the officers said: ‘better kill buffalo than have him feed the Sioux.'" Although Sheridan added that "if I could learn that every buffalo in the the northern herd were killed I would be glad," some indications point to a groundswell of military opposition to the killing. (The Military and United States Indian Policy, p. 172) In 1873, the Secretary of War was forwarded a letter from Major R.J. Dodge, endorsed by [General] Pope and Sheridan, that addressed the problem. The Secretary of War also approved Sheridan's request which seemed to indicate the general's own ambivalence on the subject, to authorize Col. De L. Floyd Jones "to put a stop to their wholesale destruction." Several officers protested the wanton destruction to Henry Bergh, president of the America Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. The army, while anxious to strike against the Indians' ability to continue their resistance, did not make the virtual extermination of the American bison part of its official policy; in some cases, individual officers took it upon themselves to try and end the slaughter. (The Military and United States Indian Policy, p. 171)

While evidence seems to point to the existence of an official policy, the debate about whether one actually existed still continues (as noted in the above paragraph). Perhaps reading accounts by people who lived in those times will provide some interesting insight:

This animal which has been for years almost the only food of the Plains Indians (more especially of late years since the diminution of what they call small game, deer, antelope, etc. in contradistinction the buffalo which is large game( has receded before civilization just as the Indian has, until now the vast single herd which formerly covered the whole Western country is divided by the Union Pacific Railroad into two comparatively small herds, entirely distinct from each other. (Adventures on the Western Frontier, p. 241)

The buffalo herd has been called the natural commissariat of the Plains Indians, and it has become reduced it roams about the region it inhabits in search of food followed by the Indians who cannot be subsisted without it. Wherever this herd goes the Indian is bound to follow. So inexorable is this law that grave international questions are liable to turn upon the movement of a buffalo herd. That the number of buffalo has decreased I think there can be no question, and the reduction of the Indian is a corollary of this and of some others to which I will allude. (Adventures on the Western Frontier, p. 241) ...But civilization has introduced amongst them various causes tending to check the reproduction and decrease their numbers. The smallpox and other diseases incident to their contact with civilization carry off so many, so many at time as almost to destroy tribes. But in the absence of any proper census the most conclusive argument of a decrease rests I think upon this consideration which is equally applicable to the buffalo. (Adventures on the Western Frontier, p. 241) This latter writes proposing that Indian Department supply each tribe with a goodly number of cows for breeding purposes.(Adventures on the Western Frontier, p. 246)

According to Colonel Homer W. Wheeler, an officer who fought with the United States' Fifth and Eleventh Cavalry for 35 years and who lived to write about his expeditions out West, "Millions of Buffalo were slaughtered for the hides and meat, principally for the hide. Some of the expert hunters made considerable money at that occupation. (Buffalo Days, p. 80)

"Buffalo hunting was dangerous sport. Although at times it looked like murder, if you took a buffalo in his native element he had plenty of courage and would fight tenaciously for His life if given an opportunity. Like all other animals, the buffalo scented danger at a distance and tried to escape by running away, but if he did not escape he would make a stand and fight to the last, for which every one must respect him. (Buffalo Days, p. 82.)

Some of the habits of the Buffalo herds are clearly fixed in my memory. The bulls were always found on the outer edge, supposedly acting as protectors to the cows and calves. For ten to twenty miles one would often see solid herds of the animals. Until the hunters commenced to kill them off, their only enemies were the wolves and coyotes. A medium-sized herd, at that time, dotted the prairie for hundreds of miles, and to guess at the number in a herd was like trying to compute the grains of wheat in a granary. (Buffalo Days, p. 81)

"The stupidity of the buffalo was remarkable. When one of their number was killed the rest of the herd, smelling the blood, would become excited, but instead of stampeding would gather around the dead buffalo, pawing, bellowing and hooking it viciously. Taking advantage of this well-known habit of the creature, the hunter would kill one animal and then wipe out almost the entire herd." (Buffalo Days, p. 82)

General Custer had this to say:

"To find employment for the few weeks which must ensue before breaking up camp was sometimes a difficult task. To break the monotony ad give horses and men exercise, buffalo hunts were organized, in which officers and men joined heartily. I know of no better drill for perfecting men in the use of firearms on horseback, and thoroughly accustoming them to the saddle, than buffalo-hunting over a moderately rough country. No amount of riding under the best of drill-masters will give that confidence and security in the saddle which will result from a few spirited charges into a buffalo herd." (My Life on the Plains, General Custer, p. 111)

In 1873 over 750,000 hides were shipped on the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad alone, and it is estimated that over 7.5 million buffalo were killed from 1872 to 1874. (General Pope and U.S. Indian Policy, p. 179)

An Army Doctor:

"'In the fall of 1885, when I, as a young acting assistant surgeon, United States Army, was stationed with A Troop, Fifth Cavalry for a short time at Cantonment, Indian Territory, we had several bands of Cheyennes under our care. Among the chiefs we had Stone Calf, Little Robe, Spotted Horse and White Horse. Having learned the sign language, I had many talks with these Indians:"

"'Stone Calf and Little Robe were greatly troubled over the disappearance of the buffalo. They told me that the great spirit created the buffalo in a large cave in the Panhandle of Texas; that the evil spirits had closed up the mouth of the cave and the buffalo could not get out. They begged me to get permission from the great father at Washington for them to go and open the cave, and let the buffalo out. They claimed to know the exact location of the cave. They even wanted me to accompany them.'" --Surgeon O. C. McNary (Buffalo Days, p. 349).

Some say the

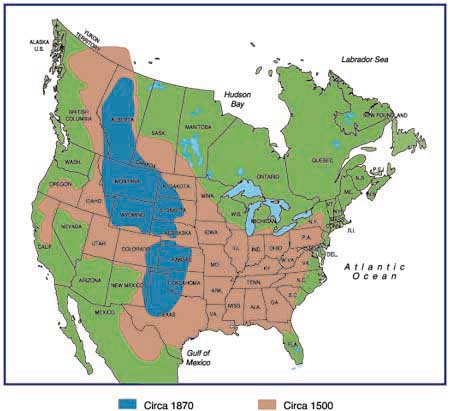

slaughter of the great buffalo herds of the West took place between 1874 and 1884. The Southern herds of in the Texas panhandle were gone as early as 1878. The picture at the

right shows buffalo populations circa 1500 (in brown) and what remained circa 1870 (in blue).

Some say the

slaughter of the great buffalo herds of the West took place between 1874 and 1884. The Southern herds of in the Texas panhandle were gone as early as 1878. The picture at the

right shows buffalo populations circa 1500 (in brown) and what remained circa 1870 (in blue).

II. Environment

Aspects

II. Environment

Aspects III. Conflict

Aspects

III. Conflict

Aspects IV. Environment

and Conflict Overlap

IV. Environment

and Conflict Overlap V. Related

Information and Sources

V. Related

Information and Sources