1. The Issue

Riding the coattails of the Viagra craze, two US companies have patented extracts of a plant grown in the Andes that has long been used by indigenous people to promote sexual function and fertility. Maca is a plant of the mustard family grown by the Andean people for centuries as a food crop and medicinal plant. In July 2001, two US patents were granted to companies who claim to have “unlocked maca’s chemical secrets.”[1] Over a dozen Peruvian farming, cultural, and environmental organizations have formed a coalition to protest the patents. They have requested the support of the Lima-based International Potato Center (CIP), one of the research centers of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). The challengers maintain that any patent of biological material is unethical and should be prohibited under international agreement.

2. Description

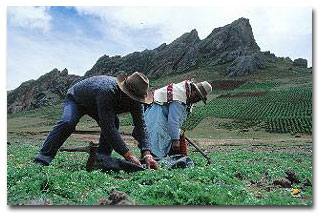

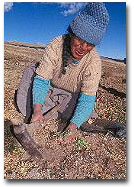

The maca plant

Maca (Lepidim meyinii or Lepidium perianium Chacon) was called “one of the lost crops of the Incas”[2] by the National Research Council of the US. A member of the radish family, it grows at altitudes up to 4,300 meters, in the intense sun, wind, and cold of the barren highlands of the Andes. Maca has also long been valued for its ability to enhance fertility in humans and livestock. Most recently, US and Peruvian companies have extracted the ingredients believed to promote fertility and produced powders and capsules for human consumption.

Maca is a member of the Cruciferae (Brassicaceae) family, related to rapeseed, Chinese cabbage, radish, and mustard. Common names of the species are: maca, Peruvian ginseng (English); and maca, maka, maca-maca, maino, ayak chichira, ayak willku. (Quechua and Spanish).[3] According to a study on maca produced by IPGRI, the International Plant Genetic Resources Initiative, maca was probably first domesticated in Junin between 1300 and 2000 years ago. It was believed to be widely cultivated especially in the 16th and 17th centuries, and once used as tax payments to the Spanish administrators.

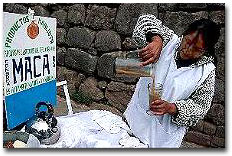

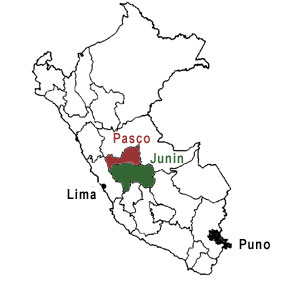

Today

it is cultivated primarily in the departments of Junín and Cerro de Pasco

in Peru. It is most frequently consumed domestically as a health drink,

often blended at roadside or market stands with fruit or vegetables. In

the Andes, indigenous people use it the same way they have for generations,

as a potato-like food source and as a food supplement for livestock. The

tuberous roots are dried, boiled, and made into jam and pudding. While

it is appreciated for its rich vitamin and protein content, its value

as a sexual performance and fertility enhancer is also part of its appeal.

Today

it is cultivated primarily in the departments of Junín and Cerro de Pasco

in Peru. It is most frequently consumed domestically as a health drink,

often blended at roadside or market stands with fruit or vegetables. In

the Andes, indigenous people use it the same way they have for generations,

as a potato-like food source and as a food supplement for livestock. The

tuberous roots are dried, boiled, and made into jam and pudding. While

it is appreciated for its rich vitamin and protein content, its value

as a sexual performance and fertility enhancer is also part of its appeal.

Once nearly extinct, Maca was cultivated more extensively when word spread of its medicinal properties and a global market opened. Its largest overseas markets are Japan and Europe, where it is usually imported in its gelatinized form and sold as powder or in capsules.

Marketing maca

The largest Peruvian company that markets Maca derivatives for medicinal purposes is Quimica Suiza, the Peruvian distributor for pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca. According to the Centro Internacional de la Papa (CIP) (see Legal Cluster below), Quimica Suiza has worked closely with CIP to invest more than $1 million dollars in maca research and development since 1994.[4] Exports to Japan in 1999 totaled about $150,000.

|

Several companies in the US purchase raw maca directly from farmers, and some own their own farms. Herbs America, the US-based makers of Maca Magic, work directly with Peruvian farmers to produce raw tubers, and local manufacturers to produce the derivatives. In their promotional material, they go to great lengths to assure customers that the maca is grown without pesticides and with consideration for the environmental concerns of the Andean ecosystem. While some companies operate with sensitivity to the cultural, environmental, and economic concerns of the indigenous farmers, no national or international regulations monitor the production of maca. So far, the result of increasing international demand has been overproduction and lower prices for farmers.[5] It is likely that there will be other burdens on the region with diverse, and perhaps unforeseen, repercussions. The US patents at issue are on the components of the maca plant, not the plant itself. The active ingredients can be extracted in a number of different ways, and each company claims to have found the best method. The patents do not preclude all extracts of maca--only those that duplicate the process described in the patents. (See Legal Cluster below) It is not clear how the patents might affect maca farmers or the future of maca cultivation. What is clear to many is that the patenting of maca derivatives amounts to biopiracy—the stealing of biologically-based knowledge for profit that is not shared with those who originated the knowledge. |

|

3.

Related Cases

3.

Related Cases

Basmati: Dispute over the rights to the name "Basmati."

Budweis - Dispute between the US and the Czech Republic over the rights to the name "Budweiser."

Canola - Dispute between Saskatchewan farmers and Monsanto Company over the rights to grow canola.

Grappa: Dispute between South Africa and the European Union over the alcoholic beverage Grappa.

Kimchi:

Dispute between South Korea and Japan on the rights to produce Kimchi.

Mummy: Ownership of Egyptian artifacts in museums around the world.

Neemtree - Dispute between the US and India over rights to products from the neem tree.

Scotch: Scotland's intellectual property rights to the alcoholic beverage.

Tequila - Mexico's demand that tequila be protected as a "geographically indicated product" under intellectual property law.

Cases about Peru and agriculture

Coca - The devastating impact on the environment by the production of cocaine

Pisco

- Trade disputes over pisco, the traditional alcohol of Peru

4. Author and Date

E. Jane Gindin

December 2002

The

US Patent Office has issued two patents

based on the components of the maca plant. An additional patent application

is pending.

US

Patent No. 6,267,995—Pure World Botanicals, Inc.

Issued July 31, 2001

Extract of Lepidium meyenii roots for pharmaceutical applications.

Applications pending in Australia, the European Patent Office, and at

WIPO.

US Patent No. 6,093,421—Biotics Research Corporation

Issued

July 25, 2000

Maca and antler for

augmenting testosterone levels.

US Patent Application No. 878,141—Pure World Botanicals, Inc.

Published April 11, 2002

Compositions and methods for their preparation from Lepidium

A patent grants property rights for an invention that is novel, not obvious, and is not a duplication of prior art. A patent gives the right to “exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, selling or importing the invention.” (US Patent Office) Opponents maintain that any patent of a food product, particularly when the knowledge about the plant is public, meets none of those requirements.

| The

US Patent Office is one of only four around the world that recognizes

plant-based patents. Earlier patent attempts have involved the plant

itself, such as the enola bean and the popping bean. They were patented

by US companies that claimed to have invented

or adapted the variety or species. Both patents were successfully

challenged because it was shown that prior knowledge existed. Germplasms

of the beans had been held in the collections of CGIAR

(Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research) institutes.

The patents were declared invalid by a 1994 ruling of the United Nations

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO),

which found that anything held in CGIAR collections could not be restricted

by monopoly patents.

In contrast, the maca patents are held on the active ingredients found in the roots. The patent-holders maintain that the process of extracting the essential ingredients and the resulting product are unique. Because the maca patent is not on the germplasm but on specific ingredients, extracted because of prior knowledge of the effects of maca, the challenge is less clear. Patent opponents maintain that the indigenous knowledge must be respected, and at the least, royalties should be paid. However, there is no formal mechanism for enforcing that patent-holders pay royalties, and no mechanism for determining who should receive the royalities. |

|

5.

Discourse and Status: Disagreement

and in process

6.

Forum and Scope:

WTO, TRIPS, WIPO, CBD, and bilateral

The international community first recognized issues of traditional

knowledge in 1981, when WIPO (World Intellectual

Property Organization) and UNESCO

(United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) adopted

a model law on folklore. Biodiversity issues were first formally recognized

in 1989, when FAO published its International Undertaking on Plant Genetic

Resources.

WIPO is a specialized agency of the United Nations system of organizations. With a history dating back to 1883, it is the international body that oversees all intellectual property concerns, committed to “maintenance and further development of the respect of intellectual property throughout the world.” The standards established by the WIPO helped to form the basis of later treaties.

The first international agreement addressing rights to biological materials was the CBD (Convention on Biological Diversity), adopted in 1992. This is still the agreement embraced by opponents of patents on biological materials because it recognizes the rights of the originators of traditional knowledge. The CBD was adopted at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. According to the CBD, "the Convention establishes three main goals: the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components, and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits from the use of genetic resources."

However, it was not until the Uruguary Round of the World Trade Organization (WTO) that disputes over intellectual property could be effectively enforced by an international body. The TRIPS agreement (Trade-Related Intellectual Property) went into effect January 1, 1995. According to the WTO, TRIPS “is an attempt to narrow the gaps in the way these rights are protected around the world, and to bring them under common international rules. When there are trade disputes over intellectual property rights, the WTO’s dispute settlement system is now available.”

The

three major components of TRIPS are standards, enforcement, and dispute

settlements. It is not a worldwide patent office, but relies on the patent

system in each country to evaluate patent applications fairly. TRIPS makes

no allowances for poor countries, where the patent office may be underfunded

and understaffed, except to extend the deadline for compliance by least-developed

countries until 2006. In Prospect

magazine Shereen El Feki writes, “The World Bank reckons that it will

cost a developing country at least $1.5m just to build a barebones infrastructure

to implement TRIPS; running the system will bring further costs.” Further

extensions are a point of discussion at the Doha Round.[8]

India

is among many developing countries that protests TRIPS’ lack of protection

for patenting genetic resources. In a joint paper (with 10 other countries)

submitted to the WTO, India said, “In the absence of clear provisions

in TRIPS implementation of the agreement may allow for acts of biopiracy

and thus result in systemic conflicts with the CBD.” [9]

A

communication sent to TRIPS council members by Brazil and 10 other nations

criticized TRIPS for omitting provisions protecting traditional knowledge,

and allowing patents on biological resources. “We believe that the TRIPS

Agreement and the Convention on Biological Diversity should be mutually

supportive and promote the sustainable use of resources.”[10]

And

while most of the world (130 nations) has ratified both CBD and TRIPS,

the two are clearly at odds. Genetic Resources Action International writes:

"The Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs)

Agreement of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) threatens to make the

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) impossible to implement. Yet

as an international commitment, the CBD is as legally binding and authoritative

as TRIPs. . . . Because the two agreements embody and promote conflicting

objectives, systems of rights and obligations, many states are questioning

which treaty takes precedence over the other. In particular, TRIPs imposes

private intellectual property rights (IPRs) on the South's biodiversity

while the CBD recognises the collective rights of local communities to

the same."[11]

Vandana

Shiva, perhaps the world's foremost defender of biodiversity, maintains

that the CBD should prevail. In a December 1999 article about the US patent

of a plant material used for generations in India to treat diabetes, Shiva

wrote, "Instead of being pressured, as India has been, to implement

a perverse IPR system, through TRIPs, India should lead a campaign in

the WTO for review and amendment of the system. Meantime, India and other

Third World countries should freeze the implementation of TRIPs. While

TRIPs implementation is frozen  for

starting a process of review, we should make domestic laws which protect

our indigenous knowledge as the common property of the people of India,

and as a national heritage. The implementation of the Convention on Biological

Diversity (CBD), enables us to do this. Since the CBD is also an international

treaty, protecting indigenous knowledge via a Biodiversity Act does not

violate our international obligations. In fact, removing the inconsistencies

between TRIPs and CBD should be important part of the international campaign

for the review and amendment of TRIPs."[12]

for

starting a process of review, we should make domestic laws which protect

our indigenous knowledge as the common property of the people of India,

and as a national heritage. The implementation of the Convention on Biological

Diversity (CBD), enables us to do this. Since the CBD is also an international

treaty, protecting indigenous knowledge via a Biodiversity Act does not

violate our international obligations. In fact, removing the inconsistencies

between TRIPs and CBD should be important part of the international campaign

for the review and amendment of TRIPs."[12]

Global

support for the CBD and against TRIPS comes not only from underdeveloped

nations, but from international organizations such as WIPO. To

more closely examine concerns of genetic resources, WIPO established the

Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources,

Traditional Knowledge and Folklore. In November 2001, the committee published

the International Treaty

on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture,

which was approved by the UNFAO as a legally binding agreement. Designed

to be in harmony with the CBD, the treaty was written in response to patents

on agriculture such as neem,

turmeric, and basmati

rice and ratified by 40 nations

The Commission on Intellectual Property Rights

(CIPR) was

established by the British government to examine the interplay of IPR

and developing countries. They published their final report in September

2002 with a number of recommendations for the implementation of TRIPS,

the role of WIPO, and the need for further examination of the implications

of IPR. The WTO’s Secretary-General

responded to the report by noting two important

concerns: “One is the question of how the TRIPS Agreement, and in particular

the flexibility and options available in it, can be best applied by developing

countries in the light of their own development needs. The second ongoing

debate is that on how the TRIPS Agreement in particular and the international

framework in the area of intellectual property more generally can be improved,

especially in the light of the development dimension.” [13]

For maca, the CBD would defend the rights of the indigenous people who originated knowledge, but there is no mechanism for enforcement or means of compensation. The only forum for challenging the patent is through the WTO, which is firmly in the camp of the developed world. A legal challenge requires enourmous financial and legal resources--generally not available to a poor nation like Peru.

Hope Shand of the non-profit advocacy organization ETC group says, "We believe that the International Potato Center (CIP), as one of the CGIAR institutes, is one party that could--and should--challenge the patent. There is a precedent because the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) has challenged the enola bean patent. (See ETC group website) Also, the Peruvian government is now in the process of studying the maca situation and may decide to challenge it."[14]

While

there has been much discussion about the incompatibility of the CBD and

TRIPS in the Doho Round of the WTO negotiations, no settlement has been

made. Given the diverging interests of the developed and the underdeveloped

world, no agreement is in sight.

7.

Decision Breadth: The

United States and Peru

8. Legal Standing: Treaty

9. Geographic Locations:

a. Geographic Domain: South America

b. Geographic Site: Western South America

c. Geographic Impact: Peru

10. Sub-National Factors:

Now cultivated primarily in the Departments of Cerro de Pasco and Junin. It was probably cultivated more widely in the past, from Junin to Puno.

11. Type of Habitat:

High

altitude of Andes Mountains, up to 4,500 meters.

12. Type of Measure: Intellectual Property

13. Direct v. Indirect Impacts: Direct and indirect

14. Relation of Trade Measure to Environmental Impact

a. Directly Related to Product: Yes--maca

b. Indirectly Related to Product: Yes--medicinal supplements

c. Not Related to Product: No

d. Related to Process: Yes--farming

15. Trade Product Identification: Maca and its components

16. Economic Data

17. Impact of Trade Restriction: Medium

18. Industry Sector: Agricultural

19.

Exporters and Importers:

Exporters: The United States and Peru

Importers: The United States, Europe, and Japan

20.

Environmental Problem Type: Species

loss land

21. Name, Type, and Diversity of Species:

Name: Maca; Lepidium meyenii

Type: Tuber similar to radish

Diversity: Grows only in the highlands of the Peruvian Andes

22. Resource Impact and Effect: Low and Regulatory

23. Urgency and Lifetime: Low and annual

24. Substitutes: Other biologically-derived products purported to enhance sexual function include deer antler, bear paw, snake, and dog. Maca is unusual in the number of scientific studies that have confirmed some sexual and fertility enhancements. See tiger and tigerind case study.

25. Culture: Yes.

The indigenous people of the Andes have been cultivating, marketing, and

consuming maca since Incan times. Restrictions on the sale or use of maca

and its derivatives deprives the Peruvian people of part of their culture

and traditions. Patents deny the existence of knowledge that is essential

to the culture.

26. Trans-Boundary Issues: No

27.

Rights: Yes.

This case study is essentially about the right to have one's knowledge

respected and valued, the ethics of patents of existing knowledge, and

the related global debate.

28. Relevant Literature

[1] “PureWorld Botanicals launches MacaPure,” on PureWorld Botanicals website. Accessed 9/13/02.

[2] Lost Crops of the Incas: Little-Known Plants of the Andes with Promise for Worldwide Cultivation, Report of an Ad Hoc Panel of the Advisory Committee on Technology Innovation Board on Science and Technology for International Development, National Research Council. Washington DC: National Academy Press, 1989.

[3] This general information on maca is based on: Andean Roots and Tubers: Ahipa, arrachacha, maca, yacon. Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops. M. Hermann, J. Heller (eds.) International Plant Genetic Resources Initiative (IPGRI), 1997. Available online at: http://www.ipgri.cgiar.org/publications/ pubfile.asp?ID_PUB=472

[4] “Peruvian Farmers and Indigenous People Denounce Maca Patents,” ETC group, Genotype, July 3, 2002, accessed 10/15/02. ETC group is dedicated to the conservation and sustainable advancement of cultural and ecological diversity and human rights.

[5] ETC group

[6] ETC group

[7] ETC group

[8] Shereen El Feki, "Special Report: Intellectual Property," Prospect magazine, September 26, 2002.

[9]"India, others seek changes in TRIPS to prevent biopiracy acts," Press Trust of India, August 1, 2002. Accessed 10/15/02 at http://www.arena.org.nz/wtobiop.htm.

[10] World Trade Organization. "The Relationship Between the TRIPS agreement and the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Protection of Traditional Knowledge." June 24, 2002. WTO document number 02-3480.

[11] "Conflicts between the WTO regime of intellectual property rights and sustainable biodiversity management," GAIA/GRAIN, Issue no. 1, April 1998. Accessed 12/4/02 at: http://www.grain.org/publications/issue1-en.cfm.

[12] "The US Patent System Legalizes Theft and Biopiracy", Vandana Shiva, The Hindu, 7/28/99. Accessed 12/4/02 at http://www.organicconsumers.org/Patent/uspatsys.cfm.

[13]World Trade Organization, "Commission report is food for thought on intellectual property — Supachai," September 17, 2002. Accessed 10/15/02 at http://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news02_e/com_report_intel_prop_17sep02_e.htm.

[14]Hope Shand, email correspondence, 11/5/02.

Peru map and black

and white photos courtesy of the International

Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI)

All other photos courtesy of Jerome

Black of Herbs America.