|

ICE Case Studies

|

U.S. - Canada Dispute Over Offshore Territory Simone Lewis-Koskinen |

I.

Case Background |

Canada and the United States have a longstanding dispute over the border between the respective maritime territories of the Yukon and Alaska in the southern Beaufort Sea. The contended wedge-shaped territory is of political and economic interest to both countries because of the corresponding use and access rights to the region. The dispute is further complicated by the accelerated rate of climate change that is dramatically reshaping the Arctic seascape. As temperatures warm and ice sheets recede, large sections of the Beaufort Sea are exposed, granting access to valuable resources and transportation routes. Of particular interest to Canada and the United States are the exploitation rights to Arctic fish stocks (e.g. arctic cod), shipping lanes, and oil and gas reserves. The growth in energy demand, expansion of navigational channels and shifting migration patterns will further exacerbate the underlying tensions of the current boundary dispute. However, the strategic interests and diplomatic relations between the two countries suggest that Canada and the United States will likely reach an agreement rather than resort to violence to resolve the conflict.

The Beaufort Sea dispute is a conflict between the United States (U.S.) and Canada concerning the delineation of the international maritime boundary between the Yukon and Alaska. The conflict exemplifies the “Great Arctic Race," a multinational competition over the last remaining unclaimed territories in the Arctic. The previously impenetrable Arctic region is rapidly melting, providing new opportunities and renewed interest. Arctic territorial disputes are becoming increasingly prevalent and relevant as scientists uncover vast reserves of untapped resources and melting sea ice provides greater access to shipping routes. As the impetus to assert sovereignty over Arctic territories continues to grow, opportunities for conflict and cooperation among Arctic nations will further develop.

The Arctic nations are comprised of both littoral and non-littoral states, including Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States, so designated by their political, cultural, and economic ties to the region. However, only the U.S., Canada, Russia, Norway and Denmark possess jurisdictional claims to the Arctic seabed based on their geographical coastlines. As two of the five littoral Arctic states, both Canada and the U.S. may legally lay claim to portions of the Arctic Ocean, including control over shipping access and natural resource extraction in the Beaufort Sea.

The conflict is fundamentally defined by the existing political framework and driven by commercial interest. As the conflict evolves, the changing political and resource realities in the Beaufort Sea will shape the future relations between Canada and the U.S. The Beaufort Sea is home to a wealth of natural resources, both of biological importance and economic significance. Notably, the extractive and navigational industries have a vested interest in securing use and access rights to the area. The principle industries involved include Shipping, Oil & Gas, and Seafood.

Within the past few years, warming induced melting sea ice has begun to antagonize the conflict, fostering a sense of gravity and urgency. The conflict lay dormant while resources lay trapped beneath impenetrable Arctic conditions. As the ice sheets gradually recede, technology advances and extractive capabilities develop, both Canada and the U.S. grow anxious to exploit the projected economic potential of the region. The accelerated rate of warming has both expedited the conflict and raised the stakes as Canada and the U.S. each vie to claim their sovereign rights.

Historical Context |

|

|

The conflicting interpretations of the borderline reflect the region’s transitional sovereignty, marred by a series of convoluted maritime laws and conventions. The various regimes that governed Alaska and the Yukon were each bound by different principles and regulations that evolved with every successive administration. Prior to gaining recognition as the 49th state of the U.S. in 1959, Spain, Russia, and finally the U.S. laid claim to Alaska and surrounding seas. Settlers, explorers and entrepreneurs alike sought to make their fortune from the region’s rich natural bounty, including the wealth of resources in the Beaufort Sea. Throughout the 19th century, the Yukon Territory similarly attracted flocks of traders and adventurers, ripe with gold, land, and opportunity. Canada later acquired the Yukon upon gaining independence from Great Britain in 1931.

|

Political Context |

|

Courtesy of historicair |

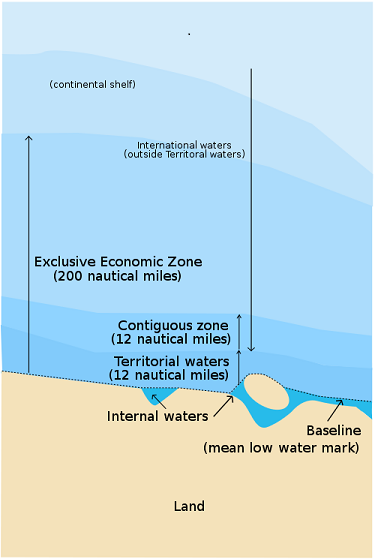

All maritime boundaries within national jurisdiction are designated under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). UNCLOS is an international maritime regime intended to ensure legal and responsible use of the ocean. The multinational treaty establishes a set of management and conservation practices that safeguard political, economic and biological interests. The convention subsequently ended the centuries old open access policy of maritime resources, granting sovereign rights to individual countries. The United Nations provides oversight to facilitate implementation and compliance. Parties to the treaty are subject to claim territorial rights under different categories: |

Begin Year: 1977

End Year: 2030

Duration: 53

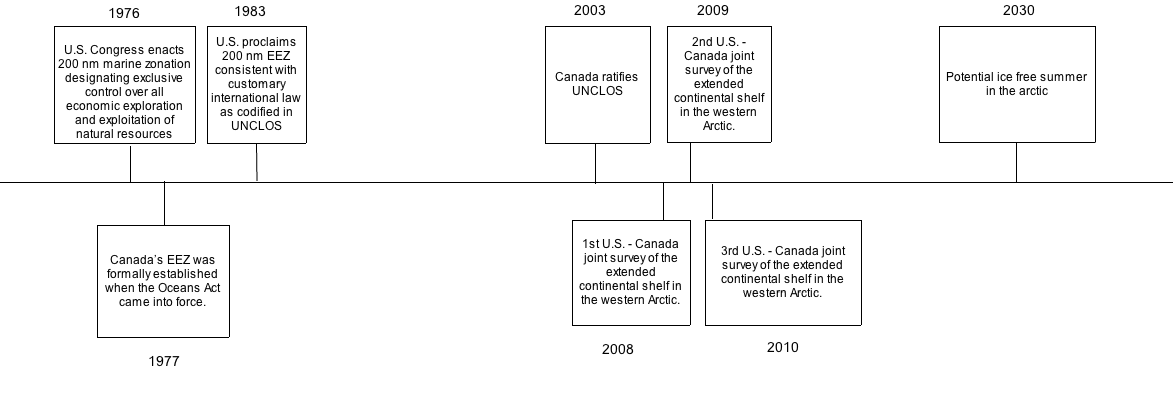

While the conflict is effectively ongoing, neither side has aggressively pursued the issue within the past three decades. The dispute originated in the 1970s, when Canada and the U.S. first laid claim to their EEZ territorial rights in 1977 and 1976, respectively (Griffiths, 2010). Over the past thirty years, there was relatively no incentive for either country to pursue territorial claims to an inaccessible region. Recently, however, scientists predict climate change will facilitate ice-free conditions by 2030, opening up greater swaths of the Beaufort Sea (U.S. Global Change Research Program, 2000). Given that each nation has already established an Arctic foreign policy prioritizing cooperation and sovereignty, the dispute will not likely extend beyond 2030.

Named after the Irish born hydrographer and explorer Sir Francis Beaufort, the Beaufort Sea covers roughly 476,000 sq km of the Arctic Ocean, situated between the north coast of Alaska and the Yukon (World Atlas). The region is geographically bound by Point Arrow, Prince Patrick Island, Banks Island and the Chukchi Sea. The disputed section is approximately the size of Lake Ontario covering just over 21,000 sq km (Griffiths, 2010).

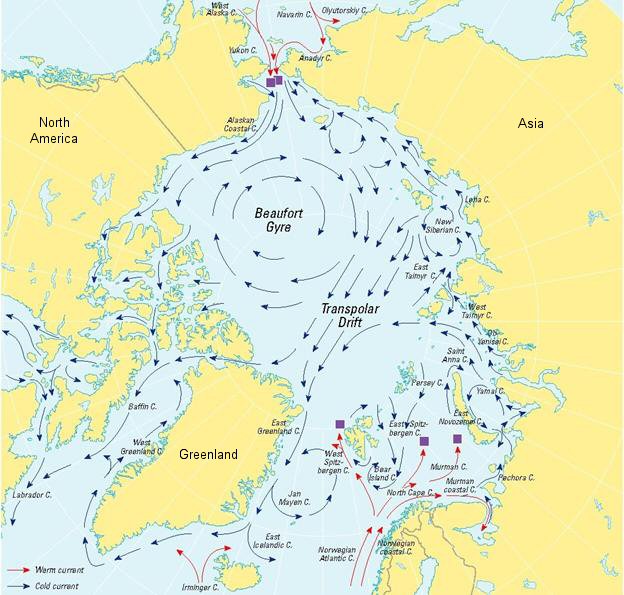

The Beaufort Sea is also home to the Beaufort Gyre, a wind driven clockwise circulation that rotates ice throughout the Arctic Ocean. Because the gyre is largely insular, sea ice in the Beaufort Sea has more time to grow and thicken (NSIDC), rendering exploration and navigation extremely difficult throughout most of the year. The Beaufort Sea is covered with sea ice for the majority of the year, running from October through July.

|

|

Courtesy of Simone Lewis-Koskinen |

Courtesty of the National Snow and Ice Data Center |

The transboundary conflict is international by nature, engaging two distinct neighboring countries. The two principle actors involved in the dispute are the United States and Canada. Within each country, the outcome is relevant across multiple sectors, including the government, industry and environmental groups.

Courtesy of U.S. Congress |

Both state and federal governments are directly implicated in the dispute. The disputed territory extends from the coastline outward, occupying both national and state jurisdictions. On the national level, the dispute has significant political, commercial, and security implications for both countries. These implications are relevant within the country and between countries as important determinants of domestic policy and foreign relations. On the state level, the dispute impacts the regional economies of Alaska and the Yukon as determined by the potential fishing and energy revenues generated. The respective Departments of Fish and Game of Alaska and the Yukon are politically entitled to territorial sovereignty within 12 nautical miles of the coastline. The U.S. and Canadian federal governments are subsequently responsible for the EEZ maritime rights extending out to 200 nautical miles. |

Courtesty of NOAA |

Global shipping companies are eager to take advantage of the melting sea ice to establish more efficient shipping routes across the Arctic Ocean and open up new areas to energy development. Seasonal openings in sea ice create limited windows of passage across the Beaufort Sea, though activity is significantly limited by weather patterns. As the ice continues to melt, scientists estimate two percent of all ship traffic will be redirected to the Arctic by 2030 (Boswell, 2010), a portion of which will pass through the Beaufort. Diminishing sea ice conditions have already resulted in a doubling of vessel traffic in the Arctic since 2005 (Ewald, 2010). While Canada and the U.S. have immediate commercial and scientific interest in future shipping activities in the Beaufort Sea, other nations have begun to express interest in Arctic navigation as well. The burgeoning navigational prospects are particularly relevant to non-Arctic states with an interest in the rights of passage throughout the Arctic. In recent years, China, Korea, Japan and others have begun to assess the commercial, political and security implications of an ice-free Arctic. Notably, China’s trade reliant economy and growing energy demands have encouraged policy makers to re-evaluate their Arctic policy and to join in formal dialogues on Arctic issues, including the potential for shipping lanes across the Beaufort (Jakobson, 2010). |

Courtesty of Joint Pipeline Office |

Scientists speculate the Beaufort Sea contains large reserves of petroleum. The USGS estimates that the Arctic basin holds roughly thirty percent of the total undiscovered natural gas resources and roughly thirteen percent of the world’s undiscovered oil resources (USGS, 2008). The U.S. EIA estimates that the disputed portion of the Barents Sea contains twelve billion barrels of oil and gas reserves (U.S. Global Change Research Program, 2000). The Canadian National Energy Board estimates the seabed below the disputed area contains 1.7bn cubic meters of gas, enough to satiate Canada’s energy demands for twenty years (Griffiths, 2010). Both parties are anxious to reap the benefits of the region’s exploitation potential to meet their respective energy demands and secure their domestic energy interests. In preparation, energy companies like Shell, BP, and Imperial Oil have already invested millions of dollars in exploration activities in the Beaufort Sea (EIA, 2009). Neither American nor Canadian oil companies are likely to abandon their multi year investments. Rather, they are likely to encourage their respective governments to enforce their jurisdictional rights in the Beaufort Sea. |

Photo by Niki K |

Arctic fisheries represent some of the most productive fisheries in the world. Fisheries managers have identified Arctic cod, saffron cod, and snow crab as likely initial target species for commercial fishing in the region (McLean, 2009). While no large-scale fisheries currently exist in the Beaufort Sea, both governments anticipate that sustained warming will enable and encourage the development of Beaufort Sea fisheries. In August of 2009, U.S. Secretary of Commerce Gary Lock approved the Fishery Management Plan for the Fish Resources of the Arctic Management Area, halting further development until further scientific assessment is completed. The plan, covering the Arctic waters of the U.S. in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas, promotes sustainable use and environmental health, requiring prospective Arctic fisheries to complete environmental assessment to safeguard the (NOAA). The Canadian Standing Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans urged the Canadian government to follow suit, advocating a moratorium on commercial fishing pending the development of a scientifically sound Arctic fishery policy (Bosewell, 2009). However, if and when those countries decide to resume fishing, who gains access to fishing rights and who will be of great interest to both government agencies and the seafood industry. |

Courtesy of NASA |

Environmental groups looking to safeguard the biological integrity of the region are likely to compete with commercial interests looking to exploit the natural resources. Groups like the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission, the Center for Biological Diversity, Oceana, Oceana, World Wildlife Fund, Pew Environment Group and others have already expressed concern over the significant risks associated with the development of drilling in the Beaufort (Common Dreams). Environmental advocates caution against the threats of habitat loss, introduction of invasive species, and ultimately the extinction of native species. In recognition of the persuasive economic incentives to pursue Arctic development, environment groups are pushing for stronger regulations and oversight that incorporate science-based management and adaptation strategies. These groups advocate broad scale the conservation practices, promoting safe, sustainable and responsible usage of the Beaufort Sea ecosystem. |

Climate Change

Scientific evidence suggests that the climate of the Arctic region is rapidly evolving, fundamentally reshaping the seascape. The changing climate will instigate a broad range of cascading effects that impact the physical and biological dynamics of the Beaufort Sea region. For example, over the past three decades, the Beaufort Sea has experienced a drastic decrease in the extent of summer sea ice, decreasing by roughly 30 percent from June1980 through June 2010. As a result, a large portion of the Beaufort Sea is ice-free, exposed and accessible, thus opening up the area to exploration and development. Recent satellite imagery suggests that the thick, multi year sea ice is thinning, reshaping the physical environment and ice-dependent ecosystem processes (Barer et al 2009).

Arctic Sea Ice June 1980 |

Arctic Sea Ice June 2010 |

Courtesty of the National Snow and Ice Data Center

The significant reduction in monthly sea ice cover reflects the recent warming atmospheric and sea surface temperature trends experienced throughout the Arctic. The effects of climate change are felt more acutely in the polar regions than anywhere else on earth, warming roughly twice as fast as the global average (Screen & Simmonds, 2010). As temperatures rise, snow and ice surfaces melt, reducing surface reflectance, which increases UV absorption. The more heat, or UV energy that is absorbed, the higher the temperature. As a result of this positive feedback loop, both the thickness and extent of Arctic sea ice has declined over the past few decades at an alarming rate (Polyak et.al., 2009). Not only is the current rate of warming likely the highest it has been in the past 1300 years, scientists predict warming trends will continue to increase throughout the century (IPCC, 2007). The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts that Arctic summers may be ice-free in as few as thirty years, resulting in a virtually sea ice-free Arctic by the year 2037 (Wang &Overland,2009). First-year Arctic summer sea ice has been declining by 8.7% per decade, while thick multi-year summer sea ice has been declining by 6.4% per decade (DFO, 2010).

Furthermore, the increase in sea and atmospheric temperatures are already changing species migration and weather patterns across the Beaufort Sea, forcing the region’s biota to shift their normal distribution patterns in search of cooler temperatures. While the specific response to climate change varies across species, scientists believe that many species will continue to migrate farther north, fundamentally affecting the physical, biological, and social structure across the Beaufort Sea ecosystem. The accelerated rate at which the climate is changing will exceed the rate at which species are able to adapt or migrate to the changing climate. Thus, many species will go extinct, move further north, or evolve. Many animals will be forced to migrate in search of new habitat and/or food supplies as their current environments change composition. However, many of these animals have adapted to a narrow range of biological parameters unique to the Arctic. Because these animals are relatively long-lived and reproduce slowly, scientists speculate that many marine mammals will go extinct because they are unable to adapt to the warming climate at the rate the change is occurring (Simpkins, 2010).

Ocean

The Beaufort Sea is a sub-arctic ecosystem shaped by seasonal shifts in climate conditions (McGinley, 2008). The region is richly diverse, home to a wide array of marine mammals, polar bears, seabirds and fish stocks largely dependent upon the seasonal sea ice. The Beaufort Sea supports several endemic populations of Arctic species, including the world’s largest Beluga whale population and several Subspecies of polar bears (COSEWIC, 2004). Nutrient influxes from the Pacific Ocean and Mackenzie River support incredible biological productivity and provide crucial food and habitat for many different Arctic species.

|

|

|

|

Photo by Rear Admiral Harley D. Nygren, NOAA |

Photo by Rear Admiral Harley D. Nygren, NOAA |

Photo by Kim Rand, NOAA |

Photo by Erika Acuna, NOAA |

The collective industrial development in Alaska and the Yukon is directly contributing to environmental degradation in the Beaufort Sea, exacerbating both climate change and the economic incentive to access the Beaufort Sea. Those industries that depend upon and exploit the resources in the Beaufort Sea are the same that will suffer from the effects of climate change as species continue to migrate further north or die off from extinction. Thus, the act and harm site are the same.

External: interstate

The conflict is international by nature as the competing interests are two distinct nation states. However, there will be opportunities for competing domestic interests to compete over limited state allocated energy leases or fishing permits. Limited access both between and within countries could foster conflict between resource users.

Resource Access (forest, minerals, water, energy, many

Photo by Trevor Maclnnis |

Competition over the estimated natural resources in the Beaufort Sea is likely to exacerbate existing tensions between the two countries as each country vies for the future control and access rights. Any future conflict between the two nations would most likely be symbolic and legal based as competing users vie for legal authority to exploit the area and subsequent resources. The increased availability will create new opportunities for growth and development, and subsequently new opportunities for conflict to develop. Similarly, the limitations of the resource base will incite competition over the dwindling reserves. Government estimates cap oil and gas production in the region at 2-7 billion barrels of oil and 3-20 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, after which the reserve will run dry (U.S. DOI, 2010). In recognition of the unique opportunities and threats associated with Arctic drilling owing to its remote location, extreme climate and dangerous sea ice, U.S. Sectary of the Interior Ken Salazar issued a moratorium on new leases until appropriate environmental assessments are conducted. The Canadian government is similarly hesitant to rush the development process, opting to wait for the review of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill review before they proceed with Arctic drilling operations. Thus, neither currently is currently engaged in resource extractition. |

Low

The projected fatality level of the dispute is low to nonexistent, resulting in fewer than 100 deaths throughout the duration of the conflict. Subsequent fatalities would likely occur between civilians (e.g. fishermen, platform operators, protestors, indigenous groups). There is very little likelihood of large-scale military involvement, though regional coast guards may be called upon to protect the security interests of resource users in the region.

Environment-Conflict Link and Dynamics:

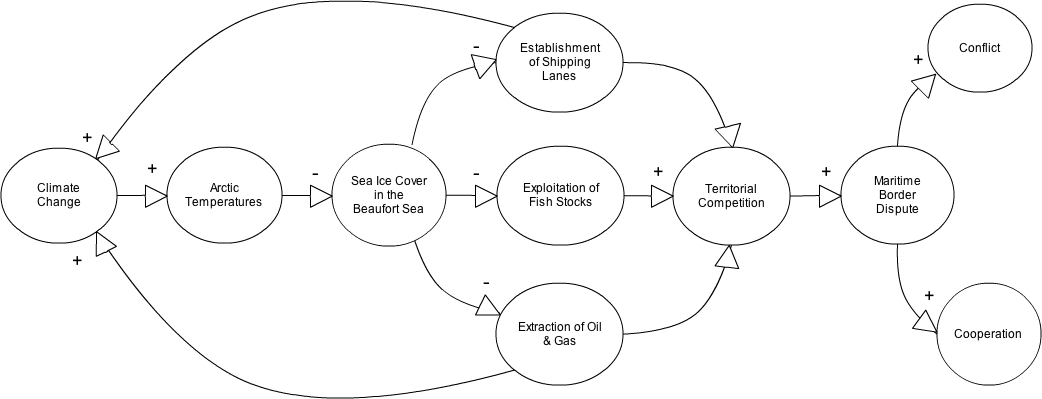

Anthropogenic induced climate change raises air and sea temperatures in the Arctic. Rapidly increasing Arctic temperatures exacerbate the rate at which arctic sea ice is melting, thus decreasing the total annual sea ice cover in the Beaufort Sea. Newly ice-free sections of the Beaufort Sea reveal portions of the ocean previously inaccessible to humans, ripe with valuable resources. Decreased ice cover and increased access will allow the United States and Canada to establish pivotal shipping lanes throughout the Beaufort Sea to maximize efficiency and decrease transportation time across the Arctic pole. Commercial fisheries will be able to find, access and exploit Arctic fish stocks. Energy industries will be able to access and extract extensive oil and gas reserves predicted to lie beneath the Beaufort Sea seabed. The creation of new shipping lanes will subsequently increase ship traffic across the Beaufort Sea, thus increasing total vessel emissions that contribute to and expedite climate change. The extraction of oil and gas reserves will be used to support the demand for and burning of fossil fuel, likewise increasing the total global output of green house gas emissions that contribute to climate change.

The value of these resources is of economic and political importance to both Canada and the United States. Seafood and oil are valuable commodities in the global market, while the control of shipping lanes yields political clout and supplements national revenues. Thus, both nations are vying for the territorial rights to access and control the Beaufort Sea resources. Both countries claim territorial rights to the Beaufort Sea under the United Nation’s Law of the Sea treaty, granting resource and use rights to signatories of the treaty within 200 nautical miles of their Exclusive Economic Zone. The two countries are disputing the maritime boundary demarcation between the U.S. Alaskan territory and Canadian Yukon. The two proposed borderlines overlap to form a wedge of disputed marine territory containing the aforementioned resources.

The relative importance of the resources and the rapid rate at which the sea ice is melting fosters a greater sense of competition and urgency. As energy and food demands increase,the prevalence and relevancy of efficient transportation of these goods will similarly increase. As the economic and political pressures build, Canada and the United States could resort to violent conflict to secure these valuable resources if no amenable resolution is found. However, the two nations might opt for a cooperative resolution to avoid the financial, social, and political costs of violent conflict.

* The casual loop diagram conceptualizes the mechanisms for the current conflict. The pathways are relatively linear with minimal opportunity for feedback. The plus and minus signs denote the directionality of the relationship; plus signifies a positive correlation in which both elements increase or intensify while minus signifies an inverse relationship in which the increase of one element decreases the other. The current dispute provides the opportunity for cooperation or conflict between the two countries.

Bilateral

By virtue of its location, the dispute over the Beaufort Sea primarily concerns the United States and Canada. Because maritime sovereignty is determined by geographical proximity to the Arctic seabed, only those two nations with coastlines within 200 nautical miles of the Beaufort Sea present valid claims to the territory.

While subsequent use and access rights will be exclusively determined by the two countries, the influential scope of the resolution is applicable to the international community. The Arctic nations share a vested interest in fostering cooperative relations between member states to build strong partnerships. Non-Arctic states are likewise interested in the future terms of use for navigational routes through the Beaufort Sea.

The evolving political, biological and economic dynamics of the Beaufort Sea will both create opportunities for future conflict as well as facilitate conflict resolution. The official Arctic foreign policies of Canada and the U.S. recognize the unique opportunities available in the region to support their national economies, foster multinational partnerships and develop political leverage points. To best protect and maintain their respective interests, both Canada and the U.S. promote the use of cooperative means to foster international relations. As climate change continues to degrade the Arctic environment thus exacerbating the impetus to formally delineate sovereignty, both nations are expected to work together to reach a cooperative agreement. Previous cooperative efforts to launch joint survey missions suggest the two nations are not only able to work together, but are willing to resolve the dispute without resulting to violent means. Furthermore, the two nations' historical cooperation and close proximity provide additional indicators that the countries will likely seek an agreement via cooperation.

Canadian Arctic Foreign Policy |

|

Canada’s Arctic foreign policy strongly advocates responsible use of the Arctic environment, prioritizing lawful assertion and recognition of Canadian sovereignty in the region. Canada strives to clearly define and address Arctic governance and related issues by gaining reorganization of the full extent of Canada’s continental shelf and resolving boundary issues, including the Beaufort Sea dispute (FAITC). Strategic implementation of Canada’s policy prioritizes bilateral relationships, acknowledging the U. S. as their important partner and adversary in the Arctic region. |

|

U.S. Arctic Foreign Policy |

|

| U.S. Arctic foreign policy has shifted priorities from research to security and sovereignty interests to reflect the growing interest in protecting U.S. Arctic interests related to human activity and homeland security (Vancouver Sun). The rapidly changing climate has focused American efforts on safeguarding American sovereign rights, including resource rights and jurisdictional claims. The directive further underscores the importance of international cooperation to alleviate existing or future tensions, in addition to the importance of U. S. ratification of UNCLOS to legally ensure American sovereign rights (Vancouver Sun). |  |

234 : ILULISSAT - Ilulissat Declaration: Legal Regimes to the Rescue?

224 : GREENLAND - Possibility of Greenland Secession from Denmark

220 : MACKERAL - Mackeral Migrations Patterns, Climate Change, and a New Fish War

217 : CANADA-EEZ - Expansion of Canada's EEZ

215 : ANTARCTICA - Antarctica, Ownership, and Climate Change

189 : CASPOI - Caspian Sea and Disputes over Sovereignty

185 : NORTHWEST-PASSAGE Canadian Sovereignty at the Northwest Passage

140 : RUSSOIL - Russian Oil, Indigenous People and Environment

121 : BARENTS - Barents Sea and Norway's and Russia's Claims

036 : ALASKA - The United States-Canada Border Dispute

Literature Cited

Alaska Department of Fish and Game (2010). Climate Change Strategy

Arctic Climate Impact Assessment (2004) Impacts of a Warming Arctic

Arctic temperature amplification. Nature 464, 1334-1337. doi:10.1038/nature09051

Barber et al. (2009).Perennial pack ice in the southern Beaufort Sea was not as it appeared in the summer of 2009. Geophysical Research Letters, 36 (24): L24501 DOI: 10.1029/2009GL041434

Boswell, R. (2009). Canada considers Beaufort Sea fishing moratorium. National Post. Accessed 11 December 2010. Website <http://www.nationalpost.com/news/story.htm?id=1925427>

Boswell, R. (2010). Arctic Shipping will hasten ice melt, study says. Edmonton Journal

Common Dreams. Interior’s Offshore Drilling Announcement: Arctic Ocean Still at Risk. Accessed 1 December 2010. Website <http://www.commondreams.org/newswire/2010/12/02-5>

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (2004). COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the beluga whale Delphinapterus leucas in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. ix + 70 pp.

Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (2010). 2010 Canadian Marine Ecosystem Status and Trends Report. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Sci. Advis. Rep. 2010/030.

Ewald, J. (2010). US collaborates with Arctic Coastal States to improivde nautical charts

Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada. Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy Pamphlet. Accessed 3 December 2010. Website <http://www.international.gc.ca/polar-polaire/canada_arctic_foreign_policy-brochure-la_politique_etrangere_du_canada_pour_arctique.aspx?lang=eng>

Gautier, D. et al., (2009). Assessment of undiscovered oil and gas in the Arctic Science 324 (5931) 1175-1179

Griffiths, S. (2010) Canada and USA Start Joint Beaufort Sea Survey. BBC News

Jakobson, L. (2010). China Prepares for an Ice free Arctic. SIPRI Insight on Peace and Security

L. Polyak, et.al., (January 2009). History of Sea Ice in the Arctic, in Past Climate Variability and Change in the Arctic and at High Latitudes, U.S. Geological Survey, Climate Change Science Program Synthesis and Assessment Product 1.2

McGinley, M.(2008). Beaufort Sea large marine ecosystem. In: Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. Cutler J. Cleveland

McLean, S. (2009). Secretary of Commerce Gary Locke Approves Fisheries Plan for Arctic. NOAA Fisheries

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Arctic Fisheries. National Marine Fisheries Service. Accessed 10 December 2010. Website <http://www.fakr.noaa.gov/sustainablefisheries/arctic/>

National Snow and Ice Data Center. Procesesse: Dynamis: Circulation. Accessed 29 November 2010. Website <http://nsidc.org/seaice/processes/circulation.htm>

Screen, J.A., Simmonds, I. (April 2010). The Central role of diminishing sea ice in recent

Simpkins, M. (2010). Arctic Report Card: Marine Mammals. NOAA Fisheries Service

The United Nations. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (A historical perspective). Accessed 14 October 2010. Website <http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_historical_perspective.htm>

The White House (2009). National Security Presidential Directive and Homeland Security Presidential Directive

United States Energy Information Administration (2009). Arctic Ocean Oil and Gas Production

United States Department of the Interior (2010). Questions and Answers: The Next Five-Year OCS Oil and Gas Leasing Program (2012-2017). Accessed December 10 2010. Website <http://www.doi.gov/whatwedo/energy/ocs/QA_2012-2-17.cfm>

United States Geological Survey (2008). 90 Billion Barrels of Oil and 1.67o Trillion Cubic Feet of Natural Gas Assessed in the Arctic

United States Global Change Research Program (2000). U.S. National Assessment of the Potential Consequences of Climate Variability and Change

United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007). Climate Change 2007.

Wang, M., and J. E. Overland (2009). A sea ice free summer Arctic within 30 years?, Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, L07502, doi:10.1029/2009GL037820

World Atlas. Beaufort Seat. Accessed 1 December 2010. Website <http://www.worldatlas.com/aatlas/infopage/beaufortsea.htm>http://www.canada.com/vancouversun/news/story.htm?id=1d6374e1-0a0c-483e-915a-e7151f7774a9(2008).

U.S. shifts Arctic foreign policy. The Vancouver Sun

Images

Figure 1

Image created by Simone Lewis-Koskinen, Google Maps

Figure 2

Image courtesy of Historicair <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Zonmar-en.svg>

Figure 3

Image created by Simone Lewis-Koskinen

Figure 4

Image created by Simone Lewis-Koskinen, Google Maps

Figure 5

Image courtesy of National Snow and Ice Data Center, <http://nsidc.org/seaice/processes/circulation.htm>

Figure 6

Image courtesy of U.S. Congress <http://www.castle.house.gov/ConstituentServices/howcanmikehelp.htm>

Figure 7

Image courtesy of Alaska Fisheries Science Center, NOAA <http://www.afsc.noaa.gov/REFM/Stocks/fit/Beaufort.php>

Figure 8

Image courtesy of Joint Pipeline Office, <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Northstar_Offshore_Island_Beaufort_Sea.jpg>

Figure 9

Image by Niki K<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Odesa_bazaar_%285%29_sprats_.JPG>

Figure 10

Image courtesy of NASA <http://rst.gsfc.nasa.gov/Sect16/Sect16_1.htm>

Figure 11,12

Image courtesy of National Snow and Ice Data Center, Google Maps <http://nsidc.org/data/google_earth/>

Figure 13

Image by Rear Admiral Harley D. Nygren, NOAA <http://www.photolib.noaa.gov/htms/corp1104.htm>

Image by Rear Admiral Harley D. Nygren, NOAA <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sea_ice_terrain.jpg>

Image by Kim Rand, NOAA <http://www.afsc.noaa.gov/slideshow/slideshow_FIT-2008.htm>

Image by Erika Acuna, NOAA <http://www.afsc.noaa.gov/slideshow/slideshow_FIT-2008.htm>

Figure 13

Trevor Maclnnis <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fuel_Barrels.JPG>

Figure 14

Image created by Simone Lewis-Koskinen

Figure 15, 16

Image courtesy of CIA World Fact Book, <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/docs/flagsoftheworld.htm>