CASE BACKGROUND

Abstract:

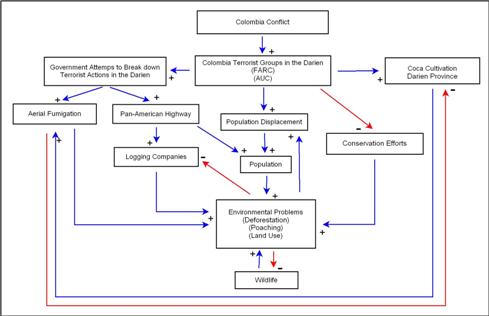

This case study demonstrates how the Colombian Civil War has impacted neighboring countries. It specifically focuses on the effect the conflict has on the Darién Province in the south of Panama, which is comprised of mainly dense tropical forest. Since the mid-1990s Colombian paramilitaries have crossed the border into Panama in pursuit of FARC guerillas. As a result, the region is now recognized as one of the most dangerous places in the world due to the increase in violent conflict and threat of possible kidnappings. As violence has increased, conservationists have been kept from doing their job in the region, which holds a national park (named a Biosphere Reserve in 1981), and RAMSAR protected wetlands. Now, excessive deforestation, poaching and overuse of land threaten the fragile ecosystems of the Darién.

Description:

Colombia’s Civil War:

Civil War has raged through Colombia for more than a century. From 1824 through 1950 the conflict was dominated by a political fight between the Liberals and the Conservatives. For more than 100 years these two parties fought for Colombian rule leading the country into extreme poverty. By the 1960s liberal peasant workers, displeased with the country’s conditions, organized into Marxist guerilla movements; namely The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and The United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC).[1]

Since then, the government, whether Liberal or Conservative, have been fighting these guerilla forces by attempting to break down their means of financing; i.e. the illegal drug trade. During the ‘Coca Boom’ in the 1970s, guerilla movements cooperated with drug lords, and fought on the same front against the government. However, as drug lords gained wealth they bought out land for large cattle ranches, which often came under attack by the guerilla troops. Consequently, since the 1970s the conflict has evolved into a drug war between right-wing paramilitary groups and left-wing guerilla organization.[2]

In the past ten years, the Colombian conflict has impacted neighboring countries. This is especially apparent in Panama where FARC have kept a stronghold in the Darién Province without much Panamanian intervention. From 1995-1997 only two incidences of tension between Panamanian police forces and guerilla troops have been reported. Both times the police came face-to-face with guerilla forces of up to 35 men, yet the incidents resulted in no violence.[3] This is a clear sign that the government is trying to underplay the presence of guerilla troops in the region. Yet, due to the increased flow of refugees from Colombian and Panamanian border cities as well as violent attacks by Colombian paramilitary groups, the government can no longer turn a blind eye to the region.

Refugee Movement and Indigenous Populations:

The conflict in the Northern regions of Colombia has put extreme pressure on the local populations forcing them to flee their homes. The area has been chosen for a possible inter-oceanic canal from the Pacific Ocean to the Caribbean Sea, it holds vast tracts of usable woodlands, and has a wealth of biodiversity and mineral deposit. These, combined, have made the area of strategic interest to paramilitary troops, and thereby fueled incursions.[4]

The first refugees from Colombia arrived in Panama in 1996 where some 400 farmers and their families fled into the Darién region.[4] At the turn of the decade refugee arrival decreased, but as the conflict intensified in both Colombia and Panama the number of displaced persons has once again picked up since 2002.[5] The arriving immigrants cause an increase in the population of the Darién province, and along with the constant movement of people, these two factors have put pressure on the areas natural resources.

Certainly, as a population accumulates some environmental damage is inevitable. However, often the damage is assessed to be indirectly caused by lacking help from relief organizations along with flawed government policies.[6] For instance, in Panama refugees have frequently been declined entrance or been deported. Between 1996 and 1997 alone some 500 refugees was send back to Colombia by the Panamanian government.[4] However, due to pressure from the international community, especially the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Panama now accepts refugees, but neglect to assist them with their basic needs.[7] Unfortunately, such policies may aggravate the environmental impact since this lack of basic goods forces refugees to seek it out in their surrounding area.

Colombian refugees do not find peace in Panama. By 1997 Colombian paramilitary groups entered the Darién in pursuit of guerilla troops and guerilla sympathizers. In March 1997 shortly after an attack on FARC’s ‘Force 57,’ which pushed thousands of Colombians to flee to Panama, the AUC attacked two Panamanian villages resulting in seven fatalities; three in the village of Titina and four in the village of La Bonga.[7] In La Bonga more than 150 paramilitary soldiers threatened to kill everyone who cooperated with guerilla forces. One survivor, Juan Madrid Oquendo, a 74-year old campesino, explained how his friend was brutally shot three times in the head while he and three others lay on the ground with their hands tied on their back. After the attack more than 250 people fled to Puerto Obaldia with no plans of returning home any time soon due to fears of retaliation.[3]

Attacks, namely in the shape of rape and robberies continued to occur during 1997 and 1998.[7] Indeed, Panama has stepped up the security in the area. In September 1999 the Panamanian government deployed 1500 additional troops from its national police force adding to the already 1500 stationed there.[8] Yet, since the country has no standing army, and the police force stationed in the Darién is outnumbered and out-gunned by the insurgents, little is done to prevent violent attacks on Panamanian cities.[9] In October 2000 an attack on the village of Nazaret took the life of a 12-year-old girl and further injured 12 other Panamanian citizens.[9]

The refugees, many of which come from indigenous tribes that have occupied the area for centuries, now find themselves in a gridlock between paramilitary troops and guerilla forces. These tribes do not consider themselves Colombians nor Panamanians, but are border populations occupying both the Darién in Panama and the Chocó province of Colombia. In the Darién three indigenous tribes (the Kuna, the Embera-Wounaan, and the Afro-Darién) combined make up a population of 60,000 people.[10] As the conflict move closer and other populations move in on their land, their traditional livelihoods have been increasingly threatened. The United Nations High Commissioner for refugees has repeatedly expressed concern for the future of indigenous peoples' livelihoods. Due to the close link between their cultural traditions and ancestral lands, forced displacement has proven exceedingly difficult for many indigenous communities to handle. According to the UNHCR, many small tribes are in risk of disappearing due to their widespread displacement.[11]

In 2003, villages inhabited by the Kuna tribe people were attacked by Colombian paramilitaries. In the attack four indigenous community leaders were killed and three foreign journalists kidnapped.[12] Overall, about 500 Kuna have been displaced and are now living as Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Boca de Cupe.[10] Due to the lack of attention by the Panamanian government, some indigenous groups are preparing to take action. In the San Blas Archipelago, Kuna tribesmen have been establishing their own self-defense forces to protect their villages.[3]

International Intervention and Environmental Impact:

After the Panamanian government agreed to let the UNHCR enter the region in 1997 to monitor refugees, they have set up a field office in the Yaviza.[13] In Panama, the UNHCR provides both legal and basic humanitarian assistance to displaced indigenous tribes and throughout the year a UNHCR staff member stay in the region to provide emergency relief.[11]

The United States (U.S.) has been intertwined in the Panamanian region for almost a decade since the construction of the Panama Canal. However, after the U.S. turned over the full operation of the Canal to the Panamanian government in December 1999, U.S. troops have left Panama.[7] Some argue that due to American plans of breaking down the international drug trade, which has become highly present in the Darién, U.S. troops disguised as drug-fighters are training, paying and commanding Colombian paramilitaries. Nevertheless, whether if these arguments are true, are still unfounded.[7] It is certain that a large sum of the $1.3 billion the U.S. are contributing to Plan Colombia goes to support the Colombian army fighting guerilla troops.[9] Undeniably, this may only make the conflict worse. To deal with the violence, the question at this point remains if the U.S. should change their current policies in the region by re-stationing troops to protect the indigenous population as well as the Colombian refugees.

While much focus have been put on the violence surrounding the Colombian conflict in the past, little attention have been paid to the impact this conflict may have on the natural environment in which it occurs. Indeed, researchers and scholars alike have mentioned the impact of the coca trade on the environment, as well as the continued terrorism of oil and gas pipelines in Colombia (See ‘Cocaine’ and ‘Colomoil’ cases).

However, as the conflict in Colombia pushes more people to flee into the Darién, the fragile environment of this significant piece of tropical rainforest is threatened due to overuse of land and the possibility of increased infrastructure to support the rising population.

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) as well as the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) both provides development assistance to the region. A three-year six-million-dollar development program by USAID is aimed at increasing economic opportunities, including construction of small infrastructure and the promotion of ecotourism and improved agricultural procedures.[14] In addition, an $88 million sustainable development program supported by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) is aimed to provide additional infrastructure particularly roads in some of the densest parts of the region.[9] However, before such plans can be undertaken it is vital that sufficient Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) are conducted to fully protect the fragile ecosystems of the Darién. This may be difficult since the continuing conflict pose great dangers to environmental scientists and geographers who would carry out the assessments. Though, if completed with the appropriate EIAs to minimize environmental impact as much as possible, both of these measures may indeed improve the livelihoods of the local populations as well as open up the area to small conservation groups. (Please see the ‘Environmental Aspect’ Section below for details on the environmental impact).

Duration: [1996-Now]

The armed conflict in Colombia has been ongoing since 1964, but it has only been felt in neighboring countries in this past decade. As stated above, Panama felt this impact in 1997 when the first paramilitary groups entered the Darién Province in pursuit of FARC soldiers

Location:

Continent: North America

Region: Southern North America

Country: Panama

Actors:

The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC):

The United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC)

Panamanian Government

Colombian Government

United States

Embera-Wounaan Tribe

Kuna Tribe

Afro-Darién Tribe