| ICE Case Studies

|

Helmand Province, Afghanistan, Conflict and Climate Changeby Tim Kovach |

I.

Case Background |

One important case study that highlights the connection between climate change and conflict is the relationship among the war in Afghanistan, the drying of the vital Helmand River, and the flourishing opium trade within Helmand Province. Ongoing civil conflict and a weak central government have led to years of environmental degradation and poor mechanisms for water management. This neglect has decreased the amount of water flowing into Helmand Province from the Helmand River. This issue has been compounded by climate change, which has decreased rainfall and lowered the level of the river further. These aspects have combined to leave the region in a prolonged and significant drought. As the drought has continued, farmers in Helmand have found it increasingly difficult to grow traditional staples, forcing many of them to turn to the drought-resistant opium crop. This expansion of the opium harvest has made Afghanistan the heart of a resurgent international opium trade and has contributed to the survival and resilience of anti-government insurgents, foremost of which is the Taliban.

|

|

A.) Country Description

The Islamic Republic of Afghanistan is a landlocked Central Asian state that sits astride three geopolitically significant regions: Central Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East. The state shares borders with six other countries, totaling 5,529km. To the West it is bordered by Iran, to the South/East by Pakistan, and to the North by Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and China. The capital of and largest city in the country is Kabul, which is located in Kabul Province in the Northeastern portion of the country.

B.) Demographics

Home to 29.8 million people, Afghanistan remains one of the least developed countries in the world. The United Nations Development Programme ranked it 172/187 on its 2011 Human Development Index. The country has not gone through a demographic transition, and its fertility and mortality rates remain among the highest in the world.

Resulting from its geographic location and history, Afghanistan is a patchwork of different ethnicities and cultures. Though it retains a strong Pashtun identity, the country is, in fact, quite diverse. Pashtuns make up a plurality (42%), but not a majority of the population. Tajiks account for 27%, Hazaras 9%, Uzbeks 9%, Aimaks 4%, Turkmen 3%, Balochis 2%, and other ethnic groups 4%. Its two official languages - Dari & Pashto - are spoken by an estimated 80% of the population (50% and 35%, respectively), but more than 30 other languages are spoken throughout the country. While the vast majority of Afghans (80%) practice the dominant Sunni Islam, there is a strong Persian influence in the west, particularly in Herat. As a result, 19% of the population practices Shia Islam, the state religion of Iran.

| Table 1: Development indicators for Afghanistan | ||

Indicator |

Score |

Country Ranking |

| Human Development Index | 0.398 | 172nd

|

| Birth Rate | 37.83 births/1,000 people | 17th

|

| Morality Rate | 17.39 deaths/1,000 people | 2nd

|

| Median Age | 18.2 years old | n/a |

| Fertility Rate | 5.39 births/woman | 13th |

| Maternal Mortality Rate | 1,400 deaths/1,000 people | 1st |

| Infant Mortality Rate | 142.9 deaths/1,000 births | 2nd |

| Life Expectancy | 45.02 | 220th |

C.) History

The first Afghan state was established by the unification of ethnic Pashtun tribes under Ahmad Shah Durrani in 1747. The nation became a centerpiece of the so-called Great Game of the 19th century. This "game" was, in reality, a power play between the British and Russian empires to expand their spheres of influence further into the heart of Central Asia. The British moved east into the Pashtun tribal belt. The incursion, and the corresponding pushback by the Pashtun peoples, resulted in three separate Anglo-Afghan Wars. Though the Afghan tribesmen managed to repel the British during the First Anglo-Afghan War, the British forces took Kabul in 1879 during the Second Anglo-Afghan War. The British assisted Abdur Rahman Khan in gaining power, and they exerted considerable pressure upon him to serve their interests in subsequent years.

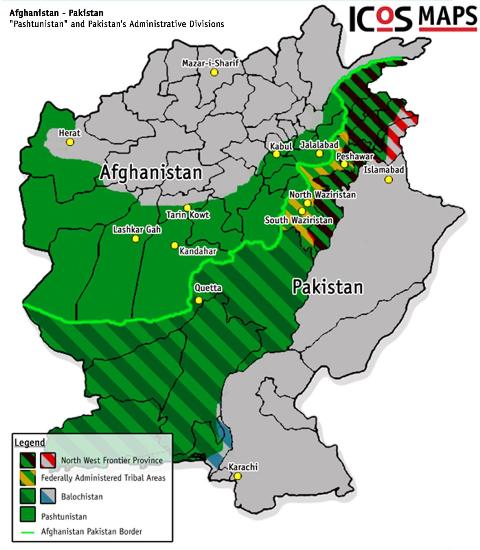

In 1893, in an effort to divide and conquer the Pashtun and Baloch peoples and create a buffer zone between Russia and British India, Foreign Secretary Henry Mortimer Durand divided Afghanistan from British-controlled India. The line he drew - the Durand Line - became the de facto demarcation; following the creation of the Pakistani state in 1947, the Durand Line remained as the international border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Despite this, neither the Pashtun people nor the Afghan government has ever recognized the border. It remains a point of contention to this day, and many Pashtun and Baloch tribesmen along the line effectively act as though this artificial barrier does not exist.

|

|

Prior to the establishment of the Pakistani state, many tribesmen called for the creation of their own nation-state - Pashtunistan. Pakistani leaders, however, wanted to create a united, multi-ethnic Muslim state. They initially provided the Pashtuns east of the Durand Line with three options: join the new Pakistani state, join the Afghan state, or create a new, independent Pashtunistan. When the time came for a referendum, however, the leaders did not carry through with their promises. The ballot contained only two options - join Pakistan or Afghanistan. The majority of the Pashtun tribesman boycotted the election as illegitimate. Of those that did cast votes, the overwhelming majority selected Pakistan. The issue has of Pashtunistan has come up several times since this point. In 1961, Afghan Prime Minister Mohammad Daoud Khan sent troops into the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan. FATA is a territory that consists of seven semi-autonomous Pashtun tribal zones; its administrative system is a relic from the old British Empire and remains a contentious issue among Pashtun nationalists. This same sense of Pashtun nationalism was a driving force behind the creation of the mujahideen in the late 1970s and its eventual successor, the Taliban, in 1994.

D.) Pashtun Culture & The Taliban

Though Pashtun tribes remain decentralized and semi-autonomous, they do retain a common culture that unifies this sense of shared ethnic identity. Villages are headed by elders, maliks. Above them sit the khans, who have control over greater numbers of people and have greater social capital and resources at their disposal. They engage with other men of their status and have a role influencing the decisions of the Afghan Central Government. All tribal leaders are subject to the decisions of councils, known as loyal jirgas. This entire social structure accords with the code of the Pashtun peoples - Pashtunwali. This system has been described as "an alternative form of social organization with an advanced conflict resolution mechanism."[1]

The social status of all Pashtun people is determined at birth, and they are taught to abide by a strict hierarchy of loyalty. This loyalty structure - qawm - places emphasis first on loyalty to family, then to extended family, and finally to the tribe. As such, the average Pashtun places far less emphasis on his/her identity as an Afghani than on his/her individual tribe. Pashtuns also follow a social hierarchy - rutbavi - that derives its basis from the respective social statuses of the tribesmen.

The Taliban are able to draw from these sociocultural concepts that they share with average Pashtuns as a means to drum up support for their battle with the Central government and for their alternative system of governance. In addition to sharing the Pashtunwali, the Taliban also shares a religious ideology that is popular among Pashtuns - Deobandi Islam. Followers of this belief system follow a strict interpretation of Islamic law that is similar to Wahhabism. They believe that moderates are non-Muslims that must be converted or punished. In order to promote their beliefs, Deobandis desire to institute a theocratic caliphate government; the Taliban carried this goal out after their rise to power in 1996. Among their more repressive policies, Taliban leaders banned movies, television, dancing, alcohol, even the popular sport of kite flying. Women were completely removed from public life and educating girls was banned. This shared religious identity provides an additional layer to understanding the level of support for the Taliban in Helmand and neighboring provinces. Many tribesmen support the system the Taliban propose. Furthermore, unlike the notoriously corrupt Afghan government, the Taliban is seen as holding a higher moral code. The Taliban has managed to effectively establish alternative systems of governance in many of the areas it occupies. Its leaders have often been able to provide swift resolution to disputes in accordance with their form of Shariah law, while the central government's judiciary remains highly ineffective.

E.) Opium Farming in Helmand Province

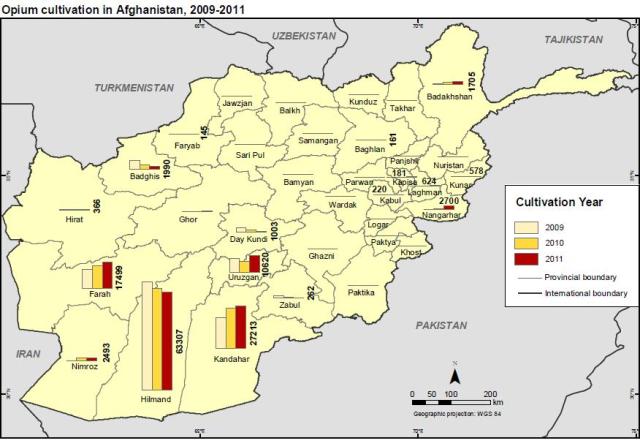

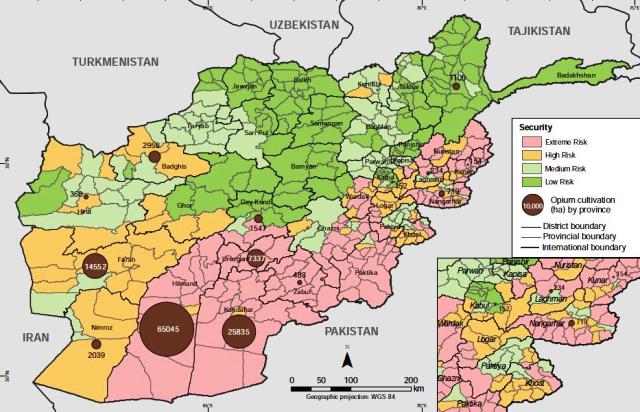

Helmand Province is home to a large Pashtun population (92% of its residents are Pashtuns), primarily members of the Durrani and Ghilzai tribes. The Province remains a flashpoint area for several reasons. The Taliban and its allies have a strong presence here, and it has been home to some of the most frequent and violent clashes between the insurgents and coalition forces in recent years. It is also the single largest opium-producing province in the world. In 2011, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimated that 131,000 hectares were under cultivation for opium production in Afghanistan. Of this, 63,307ha (48%) were located in Helmand Province. Southern Afghanistan accounted for 78% of the total lands under cultivation.

|

|

Helmand has been an agricultural center for Afghanistan for centuries due to the presence of the Helmand River. It is because of this river that the area was once known as the breadbasket of West Asia. A number of staple crops have been grown here over the years, including wheat and other cereals, sugar beets, vegetables, orchards, cotton, and seeds. Poppies have been grown in the area for over 300 years, but they have largely been relegated to one crop out of many. However, due to a number of reasons, the Helmand River has run at record-low levels over the last several years. This, combined with the myriad of socioeconomic benefits provided by growing the crop have pushed a number of farmers in Helmand to adopt the practice.

Despite fluctuating market prices and extensive eradication programs in Helmand, opium production in the province has not really fallen following its spike after the US-led invasion in 2001. The best explanation for this stems from the fringe benefits opium farming provides. Helmand province, which is highly impoverished, is largely structured as a feudal system with a strong sense of rutbavi. Accordingly, the majority of economic and political power in concentrated in the hands of a few "lords," and the rest of the residents must find ways to provide for their livelihoods within this system. These poor farmers must diversify their assets and economic opportunities; opium production provides a means for them to do this.

Opium production is very labor-intensive and cannot be readily mechanized. This provides a number of opportunities for the poor to generate off-farm income by tending to the opium crops of wealthier farmers. For the large number of landless farmers, opium production provides a means to secure access to land. Many landed farmers will sign sharecropping agreements with the landless, allowing them to tend to a parcel of land provided they meet the opium quota. Land that is not in use during the opium season and all the land between the opium harvest and next planting is thus free for the farmer to grow food stuffs. Opium is also the primary source of seasonal credit - salaam - in Helmand, a region that has limited penetration of banks and insurance. Farmers are able to put their estimated opium cultivation up as collateral to lenders, who typically provide them a loan worth 50% of the estimated market value. These asset-poor farmers can then use this cash advance to pay for the inputs (seeds, fertilizer, tools, labor, etc.) necessary to produce their opium crop. Lastly and perhaps counter intuitively, opium production can actually provide a greater source of food security for poor farmers in Helmand than wheat. Most of the opium cultivation takes place in areas with large families and high population densities and without reliable access to irrigation. Farmers in these areas simply cannot farm cereals intensively enough to feed their families. These same farmers are able to use the profit from selling the opium crop to purchase food stuffs instead.

F.) Opium Eradication Efforts

Due to the variety of benefits that opium production provides, the crop cannot be readily replaced by any other. And as market prices for it jumped following the U.S.-led invasion in 2001, production in Helmand and neighboring provinces jumped. Coalition forces and the Afghan government have undertaken a number of opium-eradication efforts since the fall of the Taliban. Many of these initial efforts involved banning and/or simply destroying the crops. These efforts ignored the significance of the crop and the lack of development throughout the region. For many of the farmers targeted, these efforts were seen as attacks on them and their livelihoods; as a result, many of them turned strongly against the Afghan government. Since this point, a number of other eradication measures have been tried. These have included cash payments for eradication, providing seeds/resources to replace opium, and larger development efforts. Ultimately, however, none of these has been success to this point.Due to the widespread lack of security in the region, the coalition and Afghan forces seem to have placed a higher priority on achieving security before development. For the people of Helmand, this is not an appropriate tradeoff; they cannot wait for security to access reliable sources of food and clean water. In many ways, this lack of development have backfired for the central government. The Taliban has been able to successful use it as illustration of the broken promises the government has made to the people of Helmand. Eradication will never take root until farmers and their families have a substitute for the socioeconomic benefits of opium cultivation. Without balancing this equation, more and more people within Helmand will find little to keep them from supporting and/or joining the insurgency.

|

|

G.) Opium & The Taliban

Opium cultivation remained a relative blip on the radar screen within Afghanistan prior to the Soviet invasion in 1979. But even by the time the Soviets left, Afghanistan was only responsible for 19% of world opium production. The real driver behind the growth of the opium market within the country was the rise of the Taliban. Despite their fundamentalist beliefs, the Taliban used opium as a tool to generate support among tribal leaders. They also used it as a major source of tax revenues. This support ended in July 2000, however, when Mullah Omar declared that opium was haram, a violation of Islamic law. Taliban officials cracked down on production with extreme efficiency and force, eliminating over 90% of production within a year.

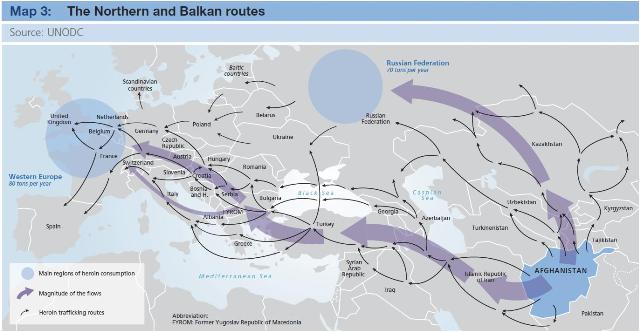

After being thrown out of power by the U.S.-led invasion, the Taliban determined that it could use opium for its own good. SInce then, the insurgency has encouraged farmers to begin producing opium. The Taliban provides security for its producers, attacking government eradication officials and defending farmers as needed. The group has also developed a stake throughout most of the production cycle. Farmers must pay a 10% tax to the local warlord/insurgent leader. The laboratories where the opium is refined into heroin pay a 15% tax. Because the vast majority of the demand for Afghan opium comes from outside the country, controlling the lines of export is another lucrative venture. Nearly all of Afghanistan's opium is exported into Southeastern Iran or Western Pakistan (FATA & Baluchistan); most of the heroin produced here then winds up in Russia and Western Europe. It is the Taliban that controls these black market routes, and they take another 15% fee during transit. Drug smugglers/traffickers have even turned to the Taliban for protection, agreeing to pay a 10-15% fee for the privilege. This diverse revenue generation scheme has produced as much as $500 million for the insurgency. Though opium is not its only source of income, it is a primary source that has not been disrupted, despite the best efforts of the coalition.

While opium production in Helmand has occurred since antiquity (legend states that Alexander the Great introduced the poppy crop), it has become much more entrenched and grown significantly larger in scope and value in recent years. In addition there has been civil conflict occurring almost continuously within Afghanistan since the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) overthrew the regime of Mohammad Daoud Khan in 1978. However, this case study focuses on the conflict that is currently occurring between the Afghan central government, headed by President Hamid Karzai, and its international allies and the diverse coalition of insurgent groups, headed primarily by the Taliban, under Mullah Mohammad Omar, the Haqqani Network, headed by Sirajuddin Haqqani, and the Hezb-e-Islami, under Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.

Beginning Year: 2001

Ending Year: N/A (Ongoing)

Duration: 10 years (as of December 2011)

Continent: Asia

Region: South Asia

Country: Afghanistan

Helmand Province in located in Southern Afghanistan and is in the heart of the insurgency. To the north it is bordered Ghor and Day Kundi Provinces, to the east by Kandahar and Uruzgan Provinces, to the south by Pakistan (Baluchistan Province), and to the west Nimroz and Farah Provinces. The capital of the Province, Lashkar Gah, is located on the Helmand River at 31 N, 64 E.

Sovereign Actors:

Non-Sovereign Actors:

1.) Helmand Villagers

2.) Drug Dealers/Smugglers

3.) Insurgents:

The major issue of concern in this case study involves the continued drying of Helmand Province and the depletion of its primary water source, the Helmand River.

Types: Climate Change, Habitat Loss

|

|

Helmand Province is located in Southern Afghanistan. The Helmand Basin region is encompassed entirely by mountains - the Hindu Kush to the North, the East Iranian ridges to the West, and the mountains of Baluchistan Province to the East and South. The lower portion of the Basin is located in the worldwide subtropical dry zone. This zone is produced because global air circulation patterns create high pressure cells over this band.The air that over Helmand is hot and dry, making it unable to produce precipitation when it reaches the ground. This, along with the lack of cloud cover allows more solar radiation to reach the surface, accounting for higher temperatures. As a result, the area is arid or hyperarid. The lower Helmand Basin receives less than 75 millimeters (3 inches) of precipitation annually. Because winters are colder than is typical for the subtropical dry zone, the basin more closely resembles the large, continental deserts of Asia than the subtropical deserts found in Northern Africa and the Middle East.

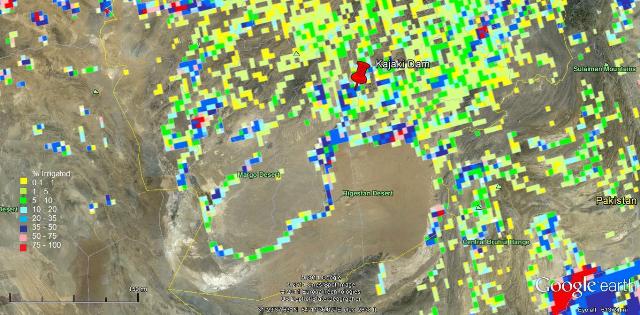

The Helmand River is the most significant geograhic feature of the Basin. The River is the the lifeblood of the region and has supported civilizations for over 6,000 years. The Helmand, which is clearly indicated in Figure 5 by the colored tiles that display irrigation intensity, is the primary source of water for the region and drains 40% of Afghanistan’s land area. It is also central to agriculture in the region; its basin is home to 13% of the irrigated land in the country. The Helmand originates high in the Hindu Kush mountains, in the Koh-i Baba Range about 90km west of the national capital of Kabul. It flows 1,900km and empties into the Sistan Basin, an environmentally unique and sensitive inland lake/wetland system that straddles the Afghanistan-Iran border. The Sistan is home to the hamons - shallow wetlands. Each of the hamouns is, at most, 3 meters deep. The large surface area of the water in tghe hamouns serves an important role in regulating the climate of the area. As the water evaporates, it lowers the air temperature in the surrounding areas while increasing relative humidity. It is possible that the lower Helmand Basin could not support life without the presence of the Sistan hamouns.

Helmand is an area of weather extremes. The calendar is essentially divided into winter and summer; summer conditions last from April-October, while winter runs from November-April. Most precipitation in the region falls during January and February. However, temperatures during this period can often fall below freezing, so agriculture is not possible at these times. Summers are extremely hot and dry, with temperatures often reaching 50 C. Summer is also accented by the so-called "Wind of 120 Days," heavy trade winds that batter the region from May-September. These winds can sustain hurricane forces, kicking up massive dust storms in the Rigestan Desert that threaten agriculture and irrigation systems. They have even buried perhaps 100 villages in hills of sand. The high winds also ensure that the Lower Helmand Basin has some of the highest evaporation rates in the world.

|

|

| Figure 6: Sistan Basin Hamouns in 1976 (courtesy of United Nations Environment Programme) | Figure 7: Sistan Basin Hamouns in 2001 (courtesy of United Nations Environment Programme) |

The rate of water discharge into the Helmand River is also prone to extremes. A study conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey found that the annual discharge totals varied five-fold during a 28-year survey period.[2] Despite these extremes, it has been possible to determine that the Helmand has run dangerously low over the last several years. An historic drought began in 1998; it has been the worst drought in the 175 years of recorded history in the region. This has combined with decades of conflict to cause a precipitous drop in the level of the Helmand River. In 2001, the Helmand ran 98% below its average annual flow. Because the hamouns in the Sistan Basin are so shallow, depend entirely on external water inputs from the Helmand, and have such high rates of evaporation, they are extremely sensitive to changes in water levels. When the Helmand failed to reach the Sistan Basin entirely in 2001, the fragile balance of the ecosystem was destroyed. Figure 6 presents a satellite image of the hamouns in 1976. Blue areas represent water between 0.5-4 meters in depth, while the dark red indicates areas of heavy reed growth in the hamouns. FIgure 7 shows the same area in 2001, the first year the Helmand River did not reach the Sistan. All of the standing water disappeared, and nearly all of the reeds have vanished, replaced by vast salt flats. The entire Sistan Basin ecosystem has essentially collapsed.

If a functioning government existed in Afghanistan, it may have been able to take some effort to mitigate the effects of this drought. However, none exists, as it has been destroyed by internal strife. The hydrologic infrastructure of the area, much of which was poorly designed in the first place, is in desperate need of repair and upkeep. The Kajaki Dam, which was funded by USAID, has not been spared. The dam continues to deal with siltation challenges, and it has been a routine target of insurgent attacks. Water tables throughout Helmand have dropped from a combination of excessive water withdraws and a decrease in groundwater recharge from the Helmand River. This vicious cycle has created famine conditions for over 6 million people in Helmand and neighboring provinces. Farmers in more than 100 villages have been forced to abandon their fields. Faced with such challenging conditions, it is perhaps not surprising that so many people in Helmand Province would turn against the Afghan Central Government and would abandon tradtional agriculture for opium farming.

While the ongoing Afghan War is an international conflict, involving a number of actors from several states, this case study focuses exclusively on the civil conflict occurring in Helmand Province between the Government of Afghanistan and the insurgents. The conflict has a number of different aspects and facets. Within Afghanistan, the central government is engaged in a prolonged fight with insurgent groups, led by the Taliban, the Haqqani Network, and Hezb-e-Islami. Parallel to this, the United States and its NATO allies are partnering with the Government of Afghanistan to battle the insurgency and promote developing within the country. The insurgency does not abide by international borders, however, so it flows back and forth across the porous border with Pakistan. Because of this haven for insurgents within Pakistan and the fact that many of these same groups are currently engaged in conflict with the Government of Pakistan, the conflict also has a regional dynamic to it. Finally, the majority of the opium that is produced within Helmand Province is sold on the international market, much of it throughout Pakistan, Iran, Russia, and Europe. Some of this funding is directed back to the insurgency, which helps to further broaden the international scope and scale of this conflict.

Afghan National Security Forces: 9,875[3]

Insurgents:

Civilians: 17,899-35,299 (estimated through July 2011)[5][6][7][8][9][10]

International Coalition Forces (as of 11/30/2011):[11]

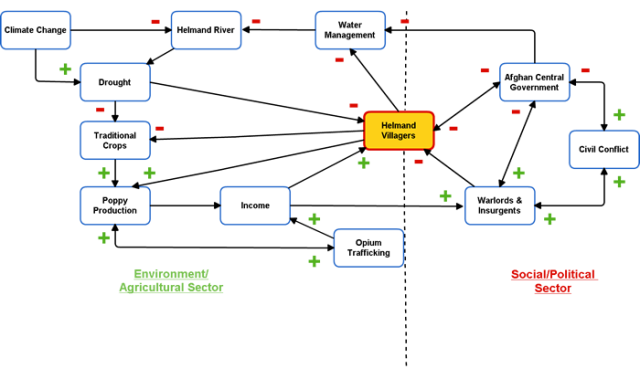

The connection between climate change, environmental degradation, violent civil conflict, and opium production in Helmand Province is dynamic and complex. The diagram is separated into an environment/agricultural sector and a social/political sector. The flow of relationships from both sectors centers on the villagers in Helmand province. Climate change and environmental degradation are significant inputs into this production, while civil conflict and instability are both inputs and outputs. The conflict is between the Afghan Central Government and insurgent groups. This continues to weaken the central government and has helped contribute to the continued presence of warlord and insurgent factions within the state; their presence further weakens the central government’s grip on power in many regions throughout the country.

Environment/Agricultural Sector:

Opium production and the health of the Helmand River are vital components in this relationship. The Helmand River exists within a very fragile ecosystem. It is essential to life within Helmand Province, but it is also extremely susceptible to climate change and environmental degradation. Since 1998, increasing temperatures and a significant decrease in the already minimal amount of precipitation within the region has led to significant decline in the flow of the River. This trend is expected not only to continue, but to get progressively worse over time as the most significant effects of global climate change are realized. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects that temperatures in Afghanistan could increase by 3.5 C by the end of the century, while precipitation could decrease by up to 15% for the Southwestern parts of the country. The Helmand River system is already under significant stress, and further increases in temperature and decreases in precipitation will likely lead to persistent periods of drought. If the Sistan Basin is unable to recover from the damage it has already sustained, this could lead to an additional positive feedback that may further exacerbate these trends. Poor maintenance of hydrologic infrastructure systems is also a significant input in this relationahip. These stressors will combine to make the farming of tradtional crops even more difficult in Helmand Province. If farmers cannot rely on the Helmand River to provide the water they need for water-intensive crops like cotton, sugar beets, and vegetables, even more of them will likely turn towards the drought-resistant poppy plant as an alternative. Since opium is such a valuable commodity, many farmers will likely see it as a better source of food security than growing traditional food stuffs, particularly in high poverty, densely populated parts of Helmand.

|

|

Social/Political Sector:

The ongoing civil conflict between the Afghan Central Government and the insurgency is a significant factor in this dynamic as well. On one hand, the fact that no viable central government has existed within Afghanistan since the Saur Revolution in 1978 has damaged social systems within the country. Having coordinated environmental management policies and mechanisms in place is particularly important for a country that lives in such a delicate environment; the lack of this compounds the consequences even further. The situation within the country has deteriorated so much over the last 30+ years that even the basic surveys/studies that are needed to upgrade these systems have not been done since the late 1970s. It is also important to understand the relationship between the insurgents and the people of Helmand Province. The high level of insecurity in the Province is a contributing factor in the growth of the opium market and the level of support for the insurgency. The people of Helmand have not been able to rely on the central government to protect them from the constant threat of bodily harm, let along to provide them with the necessary tools for economic and human development. The Taliban, in contrast, share a common religious and cultural identity with the people and have taken great effort to build rapport. They provide swift justice for the people through their ad hoc Shariah court systems. They also effectively encourage opium farming/trafficking as an economic development tool. They protect farmers from eradication efforts and provide access to the networks the farmers need to get their opium harvest from the farm into the black market. This relationship is readily apparent when one studies the correlation between opium production and number of security incidents. In 2010, the UNODC found that where security conditions were poor or very poor, opium was produced in 66% and 79% of these villages, respectively.[12]

Footnotes:

1. Johnson, Thomas and M. Chris Mason, “No Sign until the Burst of Fire: Understanding the Pakistan-Afghanistan Frontier.” International Security 32:4 (Spring 2008): 61.

2. Whitney, John W. Geology, Water, and Wind in the Lower Helmand Basin, Southern Afghanistan. Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey, 2006: 24.

3. List of Afghan security forces fatality reports in Afghanistan. 22 November 2011 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Afghan_security_forces_fatality_reports_in_Afghanistan.

4. List of Taliban fatality reports in Afghanistan. 22 November 2011 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Taliban_fatality_reports_in_Afghanistan.

5. Herold, Mark W. A Day-to-Day Chronicle of Afghanistan's Guerrilla and Civil War, June 2003 - Present. 22 November 2011 http://pubpages.unh.edu/~mwherold/dossier.

6. Herold, Mark W.A Dossier on Civilian Victims of United States' Aerial Bombing of Afghanistan: A Comprehensive Accounting. 22 November 2011 http://pubpages.unh.edu/~mwherold/dossier.

7. Herold, Mark W. The Matrix of Death: (Im)Precision of U.S Bombing and the (Under)Valuation of an Afghan Life. 22 November 2011 http://www.rawa.org/temp/runews/2008/10/06/the-imprecision-ofus-bombing-and-the-under-valuation-of-an-afghan-life.html.

8. Human Rights Watch. Troops in Contact: Airstrikes and Civilian Deaths in Afghanistan. New York: Human Rights Watch, 2008. http://www.hrw.org/reports/2008/09/08/troops-contact-0#_Toc208224420.

9. United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan. Afghanistan: Annual Report 2010, Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict. Kabul, Afghanistan: United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, 2010. http://unama.unmissions.org/Portals/UNAMA/human%20rights/March%20PoC%20Annual%20Report%20Final.pdf.

10. United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan. Afghanistan: MidYear Report 2011, Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict. Kabul, Afghanistan: United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, 2011. http://unama.unmissions.org/Portals/UNAMA/Documents/2011%20Midyear%20POC.pdf.

11. iCasualties.org. Coalition Fatalities by Province. 25 November 2011 http://icasualties.org/OEF/ByProvince.aspx.

12. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Afghanistan Opium Survey 2010: Winter Rapid Assessment. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2010: 12.

References

Central Intelligency Agency. The World Factbook - Afghanistan. 25 November 2011 https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/af.html.

Cohen, Stephen Phillip. The Idea of Pakistan. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 2004.

Herold, Mark W. A Day-to-Day Chronicle of Afghanistan's Guerrilla and Civil War, June 2003 - Present. 22 November 2011 http://pubpages.unh.edu/~mwherold/dossier.

—. A Dossier on Civilian Victims of United States' Aerial Bombing of Afghanistan: A Comprehensive Accounting. 22 November 2011 http://pubpages.unh.edu/~mwherold/dossier.

—. The Matrix of Death: (Im)Precision of U.S Bombing and the (Under)Valuation of an Afghan Life. 22 November 2011 http://www.rawa.org/temp/runews/2008/10/06/the-imprecision-ofus-bombing-and-the-under-valuation-of-an-afghan-life.html.

Hodes, Cyrus and Mark Sedra. "Chapter Three: The Opium Trade." The Adelphi Papers (2007): 35-42.

Human Rights Watch. Troops in Contact: Airstrikes and Civilian Deaths in Afghanistan. New York: Human Rights Watch, 2008. http://www.hrw.org/reports/2008/09/08/troops-contact-0#_Toc208224420.

iCasualties.org. Coalition Fatalities by Province. 25 November 2011 http://icasualties.org/OEF/ByProvince.aspx.

IPCC-AR4, Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007): 879-887. 25 November 2011 https://www.ipcc-wg1.unibe.ch/publications/wg1-ar4/ar4-wg1-chapter11.pdf.

Johnson, Thomas and M. Chris Mason. "No Sign until the Burst of Fire: Understanding the Pakistan-Afghanistan Frontier." International Security (Spring 2008): 61.

List of Afghan security forces fatality reports in Afghanistan. 22 November 2011 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Afghan_security_forces_fatality_reports_in_Afghanistan.

List of Taliban fatality reports in Afghanistan. 22 November 2011 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Taliban_fatality_reports_in_Afghanistan.

Maley, William. Fundamentalism Reborn? Afghanistan Under the Taliban. New York: New York University Press, 2001. Merz, Andrew A. Coercion, Cash-Crops and Culture: From Insurgency to Proto-State in Asia’s Opium Belt. Master's Thesis. Monterey, CA: Naval Postgraduate School, 2008.

Mansfield, David. "Responding to the Challenge of Diversity in Opium Poppy Cultivation." Afghanistan's Drug Industry: Structure, Functioning, Dynamics, and Implications for Counter-Narcotics Policy. Ed. Doris Buddenberg and William A. Byrd. Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2006. 47-74.

Palmer-Moloney, Laura-Jean (2011): Water's role in measuring security and stability in Helmand Province, Afghanistan, Water International, 36:2, 207-221

Rubin, Barnett R., and Ahmed Rashid. "From Great Game to Grand Bargain: Ending Chaos in Afghanistan and Pakistan." Foreign Affairs. 87.6 (Nov-Dec 2008): 30-44.

United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan. Afghanistan: Annual Report 2010, Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict. Kabul, Afghanistan: United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, 2010. http://unama.unmissions.org/Portals/UNAMA/human%20rights/March%20PoC%20Annual%20Report%20Final.pdf.

—. Afghanistan: MidYear Report 2011, Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict. Kabul, Afghanistan: United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, 2011. http://unama.unmissions.org/Portals/UNAMA/Documents/2011%20Midyear%20POC.pdf.

United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report. New York: United Nations Development Programme, 2011. 25 November, 2011 http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/hdi/.

United Nations Development Programme, Afghanistan. Regional Rural Economic Regeneration Assessment and Strategies (RRERS) Study, Provincial Profile for Helmand. Kabul, Afghanistan: United Nations Development Programme, Afghanistan, 2006.

United Nations Environment Programme. Afghanistan: Post-Conflict Environmental Assessment. Geneva: United Nations Environment Programme, 2003.

United Nations Environment Programme, Post-Conflict Branch. History of Environmental Change in the Sistan Basin, Based on Satellite Image Analysis: 1976-2005. Geneva: United Nations Environment Programme, 2006.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Afghanistan Opium Survey 2010: Winter Rapid Assessment. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2010.

—. Afghanistan Opium Survey 2011: Summary Findings. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2011.

Whitney, John W. Geology, Water, and Wind in the Lower Helmand Basin, Southern Afghanistan. Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey, 2006.

Last updated November 30, 2011.