| ICE Case Studies

|

Not In My Backyard! The Sarayaku's Fight Against Oil Development in the Ecuadorian Amazon |

I.

Case Background |

Ecuador’s attempts to develop its potentially large oil reserves in the last couple decades have been mired with conflict. Many indigenous people have fought to keep oil companies out, most recently the Sarayacu. In 1996, the Ecuadorian government signed a contract for petrol exploration in “Block 23”, comprising 200 000 hectares, most of which is Sarayacu territory. This was the start of an ongoing conflict between the Sarayacu people, the government and the internation oil companies.

The Sarayacu strongly oppose oil development in their territory because of

its potentially grave environmental and social impacts.

Since 1996 this conflict has occasionally erupted into violence. The Ecuadorian

army has been employed at times to quell Indian protests and protect oil workers.

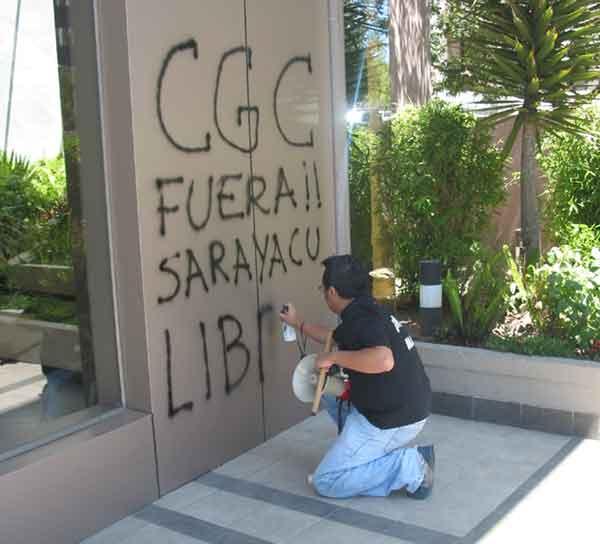

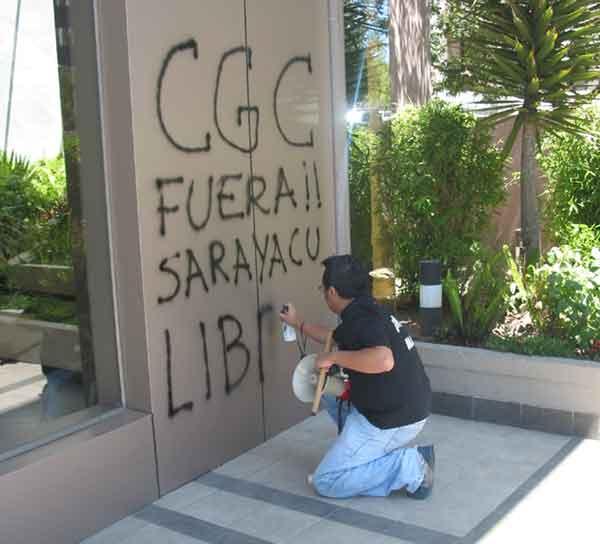

The oil companies, Argentine-owned CGC Inc (Compania General de Combustibles)

and Burlington Resources of Texas, have suffered kidnappings and constant vandalism.

According to the Sarayacu people, natives have suffered physical attacks and

other means of intimidation at the hands of the oil companies and their supporters.

The Sarayacu people are working with environmentalists around the world to

lobby against oil development in that region. The problem is that there is a

lot going against this indigenous group: high oil prices present Ecuador with

more incentive to push exploration in this region. At the same time, the US

is trying to diversify its oil sources beyond the Middle East and so looking

more toward Latin American reserves.

South America

Western South America

Ecuador

The Sarayacu conflict is over access to a natural resource. Large oil reserves happen to be situated in the Sarayacu territory and Ecuadorian government has sold the right to exploit these resources to an international oil extraction company. Oil is very valuable resource and so, although the government granted people of Sarayacu legal title to their territory in 1992, it reserved the right to subsoil resources. The problem comes in the determination that the Sarayacu own just the surface of the land. The government can’t access subsoil resources for extraction without encroaching on the Sarayacu’s (surface) territory and in some way impacting it.

This case can be classified both as a land dispute and a dispute over resources.

The Sarayacu people don’t want the oil for themselves; they just don’t

want to give companies access to their land for the purpose of oil extraction

because of all the negative environmental impact that may accompany oil extraction.

This case may be considered both a problem of scarcity and surplus. On one hand

surplus is the problem. Sarayacu territory is so well endowed with petroleum

resources that the Ecuadorian government and private interests are encroaching

upon their territory. Clearly, if they had no oil reserves on their territory

there would be no problem. On the other hand, if you look at the bigger picture

it is clearly a problem of scarcity. Oil is scarce in the world today and it

is very much in high demand, therefore the government of Ecuador has real incentives

to infringe upon the land rights of this indigenous group in order to extract

this scarce and valuable resource.

There has not been any extensive environmental damage in the Sarayacu region as of yet. (In a just a few areas trees have been felled to allow for the oil company’s initial assessments.) The Sarayacu people are resisting the oil companies because, based on the experiences of other groups in Northern Ecuador, they anticipate that oil drilling will bring problems of deforestation (SOURCE) and pollution (SINK). Oil operations in the region may also threaten its biodiversity. One endangered animal species of note lives in the region – the tapir.

Sarayacu territory is mostly pristine Amazon forest, covered with trees that may be hundreds of years old. Oil extraction would most certainly involve some deforestation, although oil companies can limit this by doing less invasive (but more expensive) drilling techniques. Oil operations also implies noise and air pollution, and perhaps even water pollution as various chemicals may runoff and contaminate surface water or groundwater.

Furthermore, the Sarayacu resist the building of roads to their territory. Currently

the only means of transportation from Sarayacu to towns in the region is by

plane or riverboat. Roads would change the environment by increasing access

to previously hard-to-reach swathes of the forest and so allowing for more pollution,

hunting, logging, other resource exploitation and settlement that encroaches

on various natural habitats. The Sarayacu people would also be affected: the

inaccessibility of their environment has been a major insulator or their lifestyle

and culture – closer contact to the towns and outside world would impact

the people, not just the environment.

This is an intra-state conflict between the Quechua indigenous group of Sarayacu who adamantly oppose oil development in their region, and on the other side the oil company, national government and military that are together facilitating oil drilling in Sarayacu territory.

10. Level of Conflict

LowTo date, this may be classified as a low level conflict.

A number of casualties have been reported on both sides, but no deaths.

The indigenous group says that many members have been physically assaulted by oil development supporters. In one instance, Sarayacu members are said to have been ambushed and kidnapped by members of another Quechua group who were employed by CGC. A number of them were attacked with wooden clubs, stones and machetes, and several suffered serious wounds. Photo documentation is offered at the group’s website, www.Sarayacu.com. In another case, the attorney representing the Sarayacu people was assaulted and threatened at gun-point. The community’s president was also assaulted in a separate occasion in 2004. These attacks have all been attributed to Sarayacu’s opposition to oil exploration. Now the Sarayacu have police stationed outside their office in Puyo, the regional capital.

For its part, the Argentine oil company, CGC, says it has suffered kidnappings, fires and robberies. In one case four oil workers were taken hostage and lectured before being returned to their camp. There have also been many cases of sabotage, with machines and buildings being damaged or burnt out of protest. So, seven years and $10 million into the project, CGC hasn’t yet been able to start drilling.

In response to pleas from the oil company for security guarantees, the Ecuadorian government on one occasion sent the military into area to protect oil company workers and allow them to proceed with their work. This provoked even more resistance from the Sarayacu people, who pledge to impede, at all costs the exploitation of its ancestral lands for oil.

The government has threatened the use of public force if the Sarayacu continue

to obstruct the oil company’s operations.

Texaco in Northern Ecuador. The case most similar to the Sarayacu conflict is a well publicized non-violent conflict that occurred in Northern Ecuador between indigenous groups and the oil company, Texaco, which operated in their region from 1964 to 1992. Right now a class-action lawsuit is still underway again over the widespread contamination caused by oil operations. The laws uit alleges that Texaco dumped millions of gallons of toxic waste into unlined pits, estuaries and rivers, exposing residents to cancer causing pollutants, fouling water for drinking and bathing and causing widespread deforestation. This case certainly colors the view of oil development that is held by all indigenous people in Ecuador.

1. Ogoni

and Oil. The Ogonis, an ethnic group that predominate in the Delta region

of Nigeria, have protested that Shell's oil production has not only devastated

the local environment, but has destroyed the economic viability of the region

for local farmers and producers. The Nigerian Federal Government, on the other

hand, has been charged with failing to enact and enforce environmental protection

against oil damage by Shell and other oil companies. Furthermore, many Ogonis

have been harassed and even killed by the Federal government for organizing

protests and threatening sabotage of oil facilities.

2. Bolivia’s Gas. Dissolution with the privatization of natural gas among the Bolivian populace has turned violent on more than one occasion, sometimes even forcing government leaders out of office. The controversy over control of this resource is further complicated by the geographic and social divide in Bolivia. The country’s natural gas fields are concentrated in the wealthier eastern provinces among businessmen with strong ties to the developed world. Bolivians of indigenous descent make up most of the 30 percent in Bolivia who live on less than one dollar per day. Such inequality has led to seemingly constant protests over control of Bolivia’s natural gas. If the issue is not soon resolved peacefully, it threatens to drive the country into civil war.

3. Chile dam. The Pehuenche indigenous people of Chile and environmentalists are struggling against a dam project on the Bio-Bio river that will force the Pehuenche off their ancestral land and flood 9,000 acres of farmland and rare temperate rainforest in Southern Chile. On June 6, 1997 the $600 million Ralco dam project was approved by the Chilean government's environmental office. This project is seen by the Pehuenche and environmentalists as a violation of the new Environmental and Indigenous laws. According to the Indigenous Law, Pehuenches cannot be forced to relocate from their land.

4. Mining in Papua New Guinea. With the third-largest gold reserves in the world, the Papua New Guinea has become a magnet for giant multinationals seeking to exploit this rich resource along with extensive silver and copper deposits. However, the development of these mineral resources has been a mixed blessing. Toxic waste from the mines has polluted many areas of the country. Local residents, particularly those of the Bougainvillea region, have taken to armed resistance to protest the destruction of habitat and to express dissatisfaction with their lack of sharing in the mining benefits.

Gold and Native Rights in the Guyana region of Venezuela

Texaco in Northern Ecuador. The case most similar to the Sarayacu conflict is a well publicized non-violent conflict that occurred in Northern Ecuador between indigenous groups and the oil company, Texaco, which operated in their region from 1964 to 1992. Right now a class-action lawsuit is still underway again over the widespread contamination caused by oil operations. The laws uit alleges that Texaco dumped millions of gallons of toxic waste into unlined pits, estuaries and rivers, exposing residents to cancer causing pollutants, fouling water for drinking and bathing and causing widespread deforestation. This case certainly colors the view of oil development that is held by all indigenous people in Ecuador.