| ICE Case Studies

|

Bolivia: Civil Unrest and Natural Gas Jason Wilcox |

I.

Case Background |

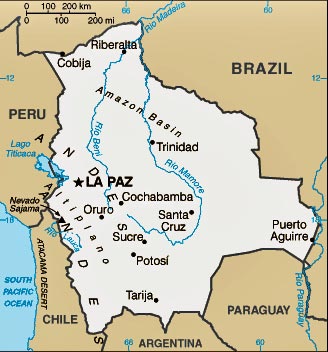

Source: CIA World Factbook

I. CASE

BACKGROUND

I. CASE

BACKGROUND

As South America’s poorest country, Bolivia is especially dependent upon exporting its natural resources abroad. Over the last ten years, natural gas has become a particularly lucrative, as well as controversial, source of income. While free-market reforms implemented in the mid-1980s have allowed the country’s economy to grow fairly steadily, they have failed to substantially reduce poverty in Bolivia (1). Dissolution with the privatization of natural gas among the Bolivian populace has turned violent on more than one occasion, sometimes even forcing government leaders out of office. The controversy over control of this resource is further complicated by the geographic and social divide in Bolivia. The country’s natural gas fields are concentrated in the wealthier eastern provinces among businessmen with strong ties to the developed world. Bolivians of indigenous descent make up most of the 30 percent in Bolivia who live on less than one dollar per day (2). Such inequality has led to seemingly constant protests over control of Bolivia’s natural gas. If the issue is not soon resolved peacefully, it threatens to drive the country into civil war.

Economic Background:

Being a landlocked country located amidst the Andes Mountains, Bolivia often suffers from high transport costs and thus benefits most from exporting light, yet valuable, raw materials (3). Given that it has the second largest natural gas reserves in South America, this resource has become a crucial part of Bolivia’s economic prospects (4). Exports of natural gas to Brazil and Argentina alone have risen to around one third of all Bolivian exports, or about $620 million (5). The economic wealth generated by natural gas has not, however, translated into prosperity for the bulk of Bolivians, particularly those of indigenous descent in the western provinces. Furthermore, argument over control of natural gas reserves, which lie in the eastern provinces of Santa Cruz and Tarija, has led to calls for greater autonomy of eastern Bolivia (6).

Ethnicity and Class Issues:

Today, about 55 percent of Bolivians are of indigenous ancestry while almost 15 percent are of Spanish descent. Around 30 percent of the population is a mix of European and Native American blood, or mestizo. The Aymara and Quechua represent the two major native language groups and live mostly in rural areas. Native American culture is also prevalent in the poorer sections of Bolivia's large cities. Bolivia's rigid social divide can be traced back to the arrival of Spanish imperial forces in the 16th Century (7). The Spanish established mines south of capital, La Paz, in 1545 to extract minerals such as tin and silver(8). As the Spanish quelled resistance to their operations in Bolivia, they set up a class sytem making the Native Americans the lower class. The artistocracy of Spanish descendents controlled almost all of Bolivia's economic resources and political power until the 1950s. In 1952, a revolution overthrew the old order and implemented democratic, social, and economic reforms. However, control over land and large businesses has mostly remained in the hands of the elite Spanish descendents. Current inequalities can also be traced to the educational system which was set up by Spanish colonists to train only the upper class of immigrants and those of European descent (9).

Conflict Over Natural Gas:

While Bolivia's natural resources have been a source of wealth, they have also exacerbated tensions between the different societal classes. As the National Chamber of Commerce described "'The exploitation of natural resources [has not] led to Bolivia's industrialization, or even to the development of a national middle class'" (10). Opposition groups within the government and Native American citizens of Bolivia have pushed for companies extracting natural resources to invest more in local infrastructure and jobs. Since the mid-1990s, foreign companies have been increasingly extracting from newly discovered natural gas fields making the resource a particularly contentious issue. The poverty of Bolivia combined with the lucrative possibilities of natural gas exporting has made control over the profits conflict-inducing. Companies such as Repsol YPF of Spain and Britain's Pan-American Energy have have introduced plans for a pipeline to export gas directly to California. It is estimated that investments such as this could increase revenue from oil and gas exports from Bolivia to $1 billion (11).

The economic, social, and geographic divides surrounding the natural gas issue have caused much civil unrest and political turmoil. After more than 30 people were killed during demonstrations in February 2003, Bolivian President Sanchez de Lozada turned to the military to bring order when protests erupted again in September 2003 over plans to export natural gas through Chile, a country with which Bolivia has had numerous border disputes and even armed conflict. After being forced out of office the next month, Sanchez was succeeded by Vice President Carlos Mesa who faced similar unrest as a result of natural gas export deals. By June 2005, Mesa was subjected to such intense pressure that he was also forced to resign from office. While Bolivia has largely been quiet since Mesa’s departure, the natural gas situation has yet to be resolved and thus continues to be a possible source of violence (12).

The intersection of armed conflict and the environment are clear in the case

of Bolivia's unrest and its natural gas fields. While they may seem to promise

more wealth for a very poor country, the natural gas resources in Bolivia have

caused much economic, social and political conflict. The exporting of natural

gas by foreign companies has caused profit for some, but dismay for many. It

is apparent that the ethnic problems which were already present in Bolivia were

exacerbated by the discovery and extraction of natural gas. Civil conflict in

Bolivia has caused many lives to be lost because of the battle over natural

gas.

Source: CIA World Factbook

Discontent began with the privatization of Bolivia's natural gas in the mid-1990s (13). Violent conflict broke out in September of 2003 when 80 people were killed during protests against natural gas exports (14).

Continent: South America

Region: Western South America

Country: Bolivia

National Government

Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada (President 6 August 1993 - 6 August 1997; 6 August 2002 - 17 October 2003)

Carlos Diego Mesa Gisbert (President 17 October 2003 - 9 June 2005)

Eduardo Rodriguez Veltze (President 9 June 2005 - present)

Government Opposition

Evo Morales (Congressman, presidential candidate, head of "Movement Towards Socialism" party and coca-growers union)

Peasant Protest Movement

Gabriel Pinto (Jailed leader of "Movement of the Landless")

Angel Duran (National leader of "Movement of the Landless")

II. Environment

Aspects

II. Environment

Aspects

Bolivia has the second largest reserves of natural gas in South America. The country has proven reserves of 54 trillion cubic feet (15). This resource has been increasingly extracted and exported since the mid-1990s.

Bolivia contains high variations in altitude which make for very different habitats relatively close to each other. The Andes Mountains and highland plateau are much drier than northern Bolivia. The Amazon basin of Bolivia’s north represents a more tropical climate with periodically heavy rain (16).

1. Nation A impacts Nation A: Control over natural gas within Bolivia’s

borders has caused tension and violence among different segments of the population

and the government.

III. Conflict

Aspects

III. Conflict

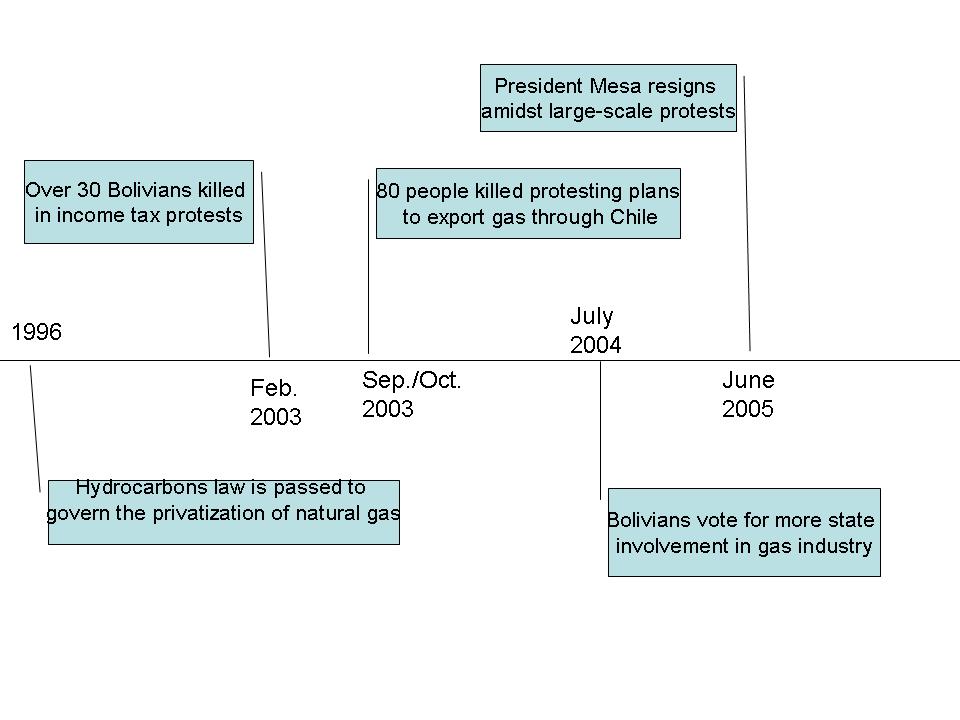

AspectsFigure 1: Timeline of Key Events

The conflict has mainly been between rural indigenous citizens and urban dwellers, with violence involving government crackdown on indigenous protesters. In August of 2004, Gabriel Pinto, leader of the Movement of the Landless (MST) was arrested after being accused of the murder of a rural mayor. The MST soon declared “‘total war against the government. . .not only with our ideas but also with sticks and stones.’” The MST and other groups representing the peasantry have organized massive demonstrations of over 100,000 people to fight what they say is corruption and transnational corporation dominance of their country while at the same time seeking to nationalize Bolivia’s natural gas industry (17). The events shaping the conflict can be seen in Figure 1, above. Beginning with the privatization of natural gas and the increased ability of foreign companies to export the resource, the conflict over who should control Bolivia's natural gas profits has led to many instances of violence and political upheaval.

Intrastate tension has increasingly divided Bolivia between eastern and western

provinces as each side struggles to gain wealth from natural gas exports. Argument

over control of natural gas reserves, which lie in the eastern provinces of

Santa Cruz and Tarija, has led to calls for greater autonomy of eastern Bolivia

(18).

The economic, social, and geographic divides surrounding the natural gas issue

have caused much civil unrest and political turmoil. After more than 30 people

were killed during demonstrations in February 2003, Bolivian President Sanchez

de Lozada turned to the military to bring order when protests erupted again

in September 2003 over plans to export natural gas through Chile. After being

forced out of office the next month, Sanchez was succeeded by Vice President

Carlos Mesa who faced similar unrest as a result of natural gas export deals.

By June 2005, Mesa was subjected to such intense pressure that he was also forced

to resign from office. While Bolivia has largely been quiet since Mesa’s

departure, the natural gas situation has yet to be resolved and thus continues

to be a possible source of violence (19).

Violence has occurred where protesters have numbered over 100,000 people (20).

Government crackdowns have resulted in estimates of up to 80 killed on multiple

occasions where the military is used to control the civilian population (21).

Therefore, most, if not all, deaths are civilian and it s difficult to get exact

numbers.

IV. Environment

and Conflict Overlap

IV. Environment

and Conflict Overlap

From the diagram, it is easy to see the relationships among several factors in Bolivia's natural gas conflict. The ethnic divides that exist in the country make for a possible foundation of conflict should there be a catalyst such as natural gas profits. Rises in Bolivian GNP, while making part of the population more prosperous, also increase the disparity between rich and poor. As more natural gas is privatized and exported from parts of the country inhabited by a particular ethnic group, violent conflict is more likely to erupt. Such a vicious cycle is what brought down the Bolivian leadership in 2005, throwing the country into turmoil.

Conflict has taken place both between the government and citizens, and between different segments of the population.

Although multiple presidents have been forced out of office by protesting citizens, Bolivia’s natural gas reserves have still not been fully nationalized as demanded by protesters. Private companies have not relinquished control over their fields as Bolivians wait for a new government to be formed and take action on this issue.

V. Related

Information and Sources

V. Related

Information and Sources