| ICE Case Studies

|

Climate Change and the Syria Crisis Erin Oakley |

I.

Case Background |

![]()

The Syrian Civil War currently ragining in the Middle East has killed over 100,000 Syrians, displaced over one third of the Syrian population, and created the largest humanitarian crisis since the Rwandan genocide. Although the protests began as a secular, pro-democracy movement, the conflict has grown increasingly polarized along ethnic and religious lines, with the majority Arab Sunni opposition movement fighting against the Syrian Arab Royal Government, led by the Shi'ite, Alawite Assad family. Although grievances against the Assad family's authoritarian rule has many sources, the years preceding the outbreak of war were plagued by the most intense drought Syria has seen in centuries. The catastrophic loss of crops, livestock, and rural livelihoods in the state in the years leading up to the civil war created a large population of displaced and impoverished farmers, who in 2011 would become the voices of protest calling for political change in Syria.

Introduction

The Syrian Civil War has rocked the Middle East for the last three years, displacing millions, killing tens of thousands, and threatening regional stability in an already tumultuous area. Although there were many factors contributing to the political unrest in 2011—including poor governance, lack of civil rights and liberties, and sectarian tensions—climate change may have contributed to the grievances of the protesters and opposition members, and to the outbreak of the conflict.

Figure 1: Map of Changing Rainfall in Syria, 2006-07 to 2007-08 |

Setting the Stage: Decreasing Rainfall and Lost Livelihoods

Although climate change is not responsible for the bloody civil war in Syria by itself, a shifting climate combined with severe resource mismanagement probably played some role in setting the stage for popular uprisings.

Between 2006 and 2010, over sixty percent of Syrian agricultural land experienced extreme long-term drought conditions. Traditional farming methods like crop rotation would normally help mitigate the effects of a particularly dry period. However, the Syrian government at the time was promoting the production of several water-intensive cash crops, including cotton, corn, and wheat. Nearly twenty-five percent of Syria’s agricultural sector consisted of cotton production by 2007. Cotton, along with wheat and corn, require complex irrigation and a lot more water than crops indigenous to the region. A rising demand for meat in rapidly growing urban population centers led to overgrazing, placing further stress on the agricultural land that would soon suffer from one of the most intense droughts the region has seen in recorded history. The national herd was reduced by up to twenty-five percent by 2010.

Thousands of small farmers in the Northeast and South of Syria lost nearly all of their crops for multiple years in a row, while some groups of pastoralists in the North lost over eighty-five percent of their livestock. The United Nations and the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies estimated a loss of 800,000 livelihoods, food security for 1 million Syrians, and an increase in extreme poverty by 2-3 million. Agricultural workers left the countryside en masse in search of employment in urban areas, increasing urban populations in places like the southern city of Deraa by over 100 percent between 2004 and 2009. The FAO estimates that 300,000 rural families moved to cities between 2006 and 2010, although other estimates are higher. A Stimson Center report on climate change and the Arab Spring suggested that 200,000 villagers abandoned the farmland surrounding Aleppo alone. Increasing rates of poverty and internal migration combined with the country’s “youth bulge” demography made for a dangerous mix of lack of opportunity and young population.

Figure 2: Protesters in Damascus, August 2011 |

Source: Wikimedia Commons user: shamsnn |

The Arab Spring

When Bashar al Assad ascended to leadership in Syria after the brutal reign of his father, international observers and domestic reformers were optimistic about the son’s potential for allowing political and economic change. The western-educated ophthalmologist seemed open to democratic reform, however, after eleven years of rule brought little or no positive change to Syria.

Following the example set out in Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, and other Arab countries, Syrians took to the streets in protest beginning March 2011. At first, protests were largely secular and non-sectarian in nature. Protesters called for limited democratic reforms, respect for human rights, and the release of political prisoners. By the end of the first week of protests, sixty-one people were killed. Soon protesters began to call for Assad’s resignation. The military was sent in to quell protests by May 2011 in key cities of Deraa, Damascus, Banyas, and Homs. Protesters soon began to organize and take up arms against the Syrian Arab Royal Government. By December 2012, the United States, Great Britain, France, Turkey, and the Gulf states recognized the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces as the “voice of the Syrian people.”

Sectarianism Rising

Although the Syrian movement began as peaceful protests for political reform, the conflict has since spiraled in both physical and ideological intensity. The rising power of religious extremist rebel groups, including al Tawhid, al Qaida, and al Nusra have transformed the conflict into one based on ethnicity and religion. Religious figures have been targeted on both sides, and civilians have been slaughtered simply for being of the opposing religious group. Shi’a, Alawite, and Christian groups have flocked to government controlled areas, while majority Sunni tend to support the opposition. In the far Northeast, Kurdish rebels have faced attacks from both government forces and Sunni extremist groups. The increasingly extreme positions of the rebel groups have helped the groups gain support from wealthy, religious foreign benefactors, however, this has led to a loss of legitimacy for the moderate opposition on the international stage, and has cost the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces support from pro-democracy outsiders like the United States and the European Union.

Regional Instability

As the Syria conflict grows deadlier, neighboring states have become concerned that the conflict will spill out of Syria’s borders. Many of the Gulf States have begun to view the war in Syria as a proxy war, with Shi'ite Iran backing Alawite leader Bashar al Assad in order to assert dominance in the region. Sunni extremists from outside of Syria have increasingly entered the conflict on the side of the opposition, while the Syrian government has received assistance from Iran and Hezbollah.

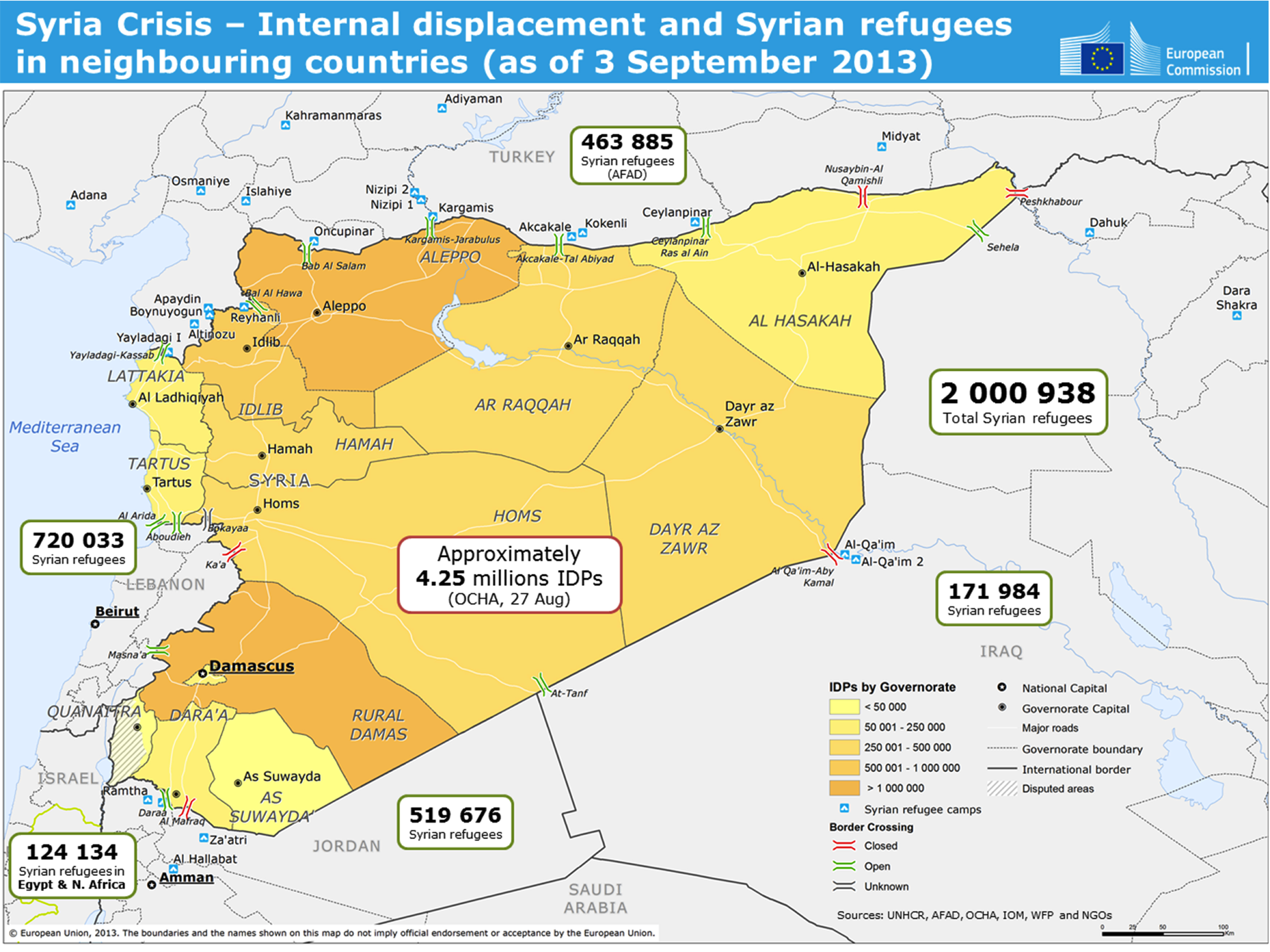

Particularly at risk is Jordan, where an already existing water scarcity problem is growing critical with the influx of over 500,000 refugees, a number that is predicted to double in 2014. Over 200,000 refugees reside in Zaatri Camp alone, located in the water-scarce northern region. The remaining refugees are referred to as “urban refugees,” although they live in both urban and rural settings within Jordanian host communities. In response to the influx of refugees in Jordan, the government has cut subsidies on healthcare, energy, and even water for everyone within the country’s borders because they cannot discriminate between Jordanian and Syrian households for basic services. Declining subsidies for basic services, increasing unemployment, and the increase in competition in the job market from low-wage Syrian refugees has contributed to already existing civil unrest in Jordan, which has led to a number of protests and riots in Jordan, with increasing intensity since late 2012.

Figure 3: Map of Refugee Distribution from the Syria Crisis as of September 2013. Source: European Commission |

Begin Year: 2011

End Year: Ongoing

Duration: Ongoing

Figure 4: Timeline of Conflict in the Syrian Civil War |

Continent: Mideast

Region: Southwest Asia

Country: Syria

Figure 5: Cities of Importance in Syria |

|

| Important Cities | Description |

| Damascus | Syria's capital city; some surrounding neighborhoods are still under opposition control, while the city is the center of the regime's power. |

| Dera'a | Site of initial protests in 2011, Dera'a witnessed the first deaths in the Syrian Civil War |

| Homs | Initially known as the "Capital of the Revolution," Homs has experienced massive damages from the Syrian government's ongoing seige. Some neighborhoods still hold out for the opposition. |

| Hama | After Syrians in Hama held major demonstrations against the Assad regime in 2011, Hama was retaken by government forces by summer 2011. |

| Aleppo | The largest city in Syria, Aleppo was taken by the Free Syria Army in July 2012. Several rebel groups are currently competing for control, reportedly enforcing sharia law. |

| Raqqa | A rebel-held city in the northeast, the regime began bombing campaigns in March 2013, which continue through the end of 2013. |

Sovereign Actors

Non-sovereign Actors

See Conflict Aspects for a description of actors.

![]()

Climate Change

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the drought Syria and the rest of the Mediterranean area experienced between 2006 and 2011 is linked to climate change and is part of a farther-reaching trend in decreased precipitation in the region that is only expected to grow more severe over time. The International Food Policy Research Institute estimated that trends in climate change and precipitation decrease would led to 29-57 percent reduction in rain-fed crops in Syria between 2010 and 2050. Water mismanagement, along with the effects of climate change on reduced water supply, has the potential of causing irreversible desertification in Syria, particularly in the poverty-stricken Northeast.

Figure 6: Map of Drought Severity in Syria, 1940s-2000s |

Dry

Agricultural Zone |

Description |

Percentage of Agricultural Production (2007) |

Drought Years, 1969-2009 |

1 |

Annual ave. rainfall above 350 mm | 48.3% |

13 |

2 |

Annual ave. rainfall between 250-250mm | 25.0% |

19 |

3 |

Annual ave. rainfall 250 mm, with 50% chance of less precipitation | 6.9% |

19 |

4 |

Annual ave. rainfall 200-250 mm | 6.6% |

21 |

5 |

Annual ave. rainfall less than 200 mm | 13.2% |

16 |

Figure 7: Map of Syrian Agricultural Zones |

Act Sites: Syria

Harm Sites: Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey

![]()

Military Conflict

Although the Syrian Civil War is a conflict between those who support the Assad regime and those who oppose it, the Syrian Civil War is far from a two-sided conflict. Assad's forces are well-armed and well-supplied, including an extensive air force and, until recently, a cache of chemical weapons. It is estimated that there are over 1,000 distinct armed opposition groups currently operating within Syria, a total of over 100,000 insurgents. Opposition forces place at various locations along the extremism scale, however, since the regime's use of chemical weapons against civilians in the suburbs of Damascus in August, the opposition has grown considerably more anti-Shi'ite and anti-Alawite. Foreign Policy recently estimated that as much as eighty percent of the opposition, about 68,000 fighters, are under the umbrella of Salafist or jihadist. These more extreme groups have a better chance of gaining support from non-state actors in the Gulf--rich Sunni extremists in Saudi Arabia and Qatar--and as a result, even moderate groups have become to use more religious rhetoric.

High

Government and opposition forces have clashed on a number of fronts, and fighting has led to the displacement of over six million people (see Figure 5). Notable centers of violence have been in Homs, opposition-controlled Aleppo, and in the suburbs of Damascus where government forces used chemical weapons to kill approximately three hundred civilians in opposition-controlled territory, nearly prompting intervention from the United States. Although a deal was reached to disarm the Assad regime of chemical weapons, conventional warfare continues unabated.

High

The toll of the violence in Syria is massive and continues to grow as the war rages on. The current estimate for war-related fatalities is over 115,000. In addition to the growing death count, over 2.1 million refugees have fled to surrounding countries, and over 6 million Syrians are internally displaced.

![]()

Figure 8: Causal Diagram--Climate Elements of Conflict in Syria |

The model above attempts to explain the climate-related aspect of the Syria crisis, based on Thomas Homer-Dixon’s model of potential sources and consequences of environmental scarcity (Homer-Dixon, 1994). A report released by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in 2011 concluded that the drought experienced by Syria in the last several years—displacing approximately 1.5 million farmers before the protests even began—is a result of human-caused climate change (Plumer, 2013). The drought, combined with a population growth rate of over two percent per year, contributed to a serious drop in agricultural productivity in the Syrian countryside, and an exodus from rural areas into urban. Notably the city of Daraa, the site of many of the initial protests in 2011, grew in population due to migration during the years preceding the war (Francesco & Werrell, 2012). Low agricultural productivity also led to decreased government income and decreased legitimacy of the dictatorship. While there are many other causes of urban and rural unrest that led to political protests, and escalation to civil war was only brought about by a violent government response, water scarcity definitely played a role in setting the stage for the Syria conflict.

Substate

Region

The level of strategic interest in Syria is extremely high, not just because of the outflow of refugees destabilizing neighboring states, but because surrounding states have become involved in the increasingly unstable state. Iran, Hezbollah, the Gulf States, and to a less extent the United States, have begun to treat Syria as a proxy war between Shi'ite and Sunni influence in the region. U.S. President Barack Obama's attempt to bring to United States to intervene in the country, as well as the arming of rebel groups by pro-democracy and pro-Sunni outside states as well as non-state actors, is demonstrative of the larger, regional struggle encapsulated by the Syrian Civil War.

Ongoing

Given the nature of the civil war in Syria, the environmental risks in surrounding nations due to climate change, and the political risks of widespread regional instability, there is a high risk that the conflict in Syria will spill over into surrounding countries, or that consequences of the Syria conflict will indirectly contribute to instrastate violence in neighboring states.

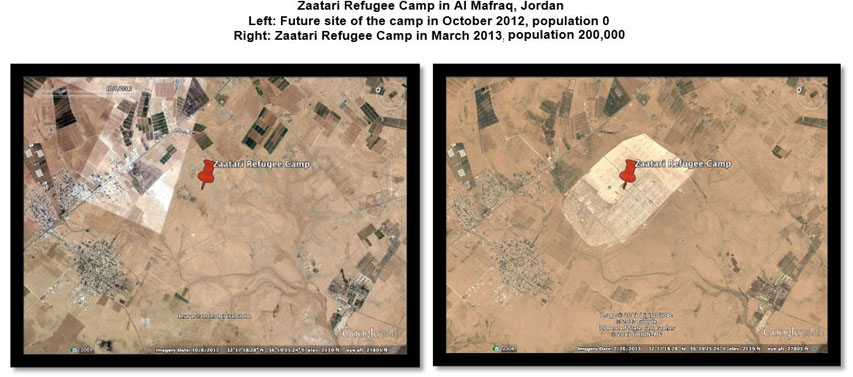

Figure 9: The Rapid Growth of Za'atari Refugee Camp |

As seen in Figure 9 above, the future site of Za'atari Refugee Camp in northern Jordan was an empty desert as recently as 2012. In just a few short months, Za'atari Refugee Camp became the seventh largest city in Jordan, with a population of over 200,000 people in March 2013, creating a four percent increase to Jordan's population. By December 2013, Za'atari's population exceeded 300,000. Northern Jordan is a particularly water scarce area, and water for the camp needs to be delivered by truck. Less than half of the refugee population in Jordan resides in the camp, which placed enormous stress on resources in the country.

Figure 10: Causal Diagram -- Climate Change Elements for Potential Conflict in Jordan |

The model in Figure 10 attempts to explain potential violent conflict in Jordan also draws from Homer-Dixon’s model, but includes the impact of refugee populations (expected to reach 600,000 by the end of 2013, ten percent of Jordan’s population) (Baker, 2013). The high number of refugees in Jordan is not only exacerbating an already existing water scarcity problem in the country, but has also led to tensions between Jordanians and Syrians as competition for employment and scarce resources increases. While Syrian refugees were initially welcomed into host communities in Jordan, relations between the two groups have become increasingly strained as the conflict drags on. The “Weakened State” variable is complicated in Jordan; the legitimacy of the state may be falling due to its inability to provide subsidies for energy and water to citizens at the same level as previous years due to the rising population. The line is drawn directly from “Water Scarcity” to “Weakened State” in this diagram, unlike that of Syria, because the situation is much more critical there and a great deal of the population is dependent on the government for water (Black, 2013). Decreased subsidies are also the result of reforms pushed by international institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF, which made development aid contingent on economic liberalization (Sly, 2012). Development aid is critical in Jordan, partially because of the decreasing availability of water in the state and the need for technical solutions. Urbanization increases water scarcity in Jordan because water is diverted from rural areas to support Amman and other urban areas (Yorke, 2013). While the Jordanian protests of late 2012 and early 2013 may not turn into violent conflict, there are clear risk factors that could lead to conflict in the near future.

![]()

Turkey, Dams, and Kurds, Conflict Within and Between Countries

Eritrea and Ethiopia: Continual Conflict

Abu-Ismali, Khalid, Abdel-Gadir, Ali, and El-Laithy, Heba. "Poverty and Inequality in Syria (1997-2007)." United Nations Development Report, 2011.

"Act Now to Stop Desertification, Says FAO." IRIN News, June 15, 2010.

Al-Riffai, Perrihan, Breisinger, Clemens, Verne, Dorte, and Tingju, Zhu. "Droughts in Syria: An Assessment of Impacts and Options for Improving the Resilience of the Poor." Quarterly Journal of International Agriculture, 51,1 (2012): 21-49.

Baker, Aryn. Will Syria’s Refugee Crisis Drain Jordan of Its Water?Time. April 4, 2013.

Black, Ian. “Jordan Jitters Over Swelling Syrian Refugee Influx.” The Guardian. July 31, 2012.

"Drought Assessment Mission to Syria." FAO, WFP, UNDP, WHO, UNICEF, IOM, August 2008.

General Martin E. Dempsey, U.S. Army to Chairman Carl Levin, Committee on Armed Services, United States Senate. July 19, 2013.

Lister, Charles. "Syria's Insurgency Beyond Good Guys and Bad Guys." Foreign Policy, September 20, 2013.

"Syria Profile." BBC News, December 12, 2013.

"The Country Formerly Known as Syria." The Economist, February 23, 2013.

Werrel, Caitlin E. and Femia, Francesco. “The Arab Spring and Climate Change: A Climate Security Correlations Series.” The Center for American Progress, The Stimson Center, The Center for Climate and Security, February 2012.

Yorke, Valerie. “Politics Matter: Jordan’s Path to Water Security Lies Through Political Reforms and Regional Cooperation.” Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research. April 2013.

Homer-Dixon, Thomas F. “Environmental Scarcities and Violent Conflict: Evidence from Cases.” International Security 19,1 (1994): 5-40.

![]()