|

Eco-Migration in Southern Africa The Outcomes of Xenophobia Patrick Egenhofer |

|

| ICE Case Studies

|

|

I.

Case Background |

|

Eco-Migration in Southern Africa The Outcomes of Xenophobia Patrick Egenhofer |

|

| ICE Case Studies

|

|

I.

Case Background |

The migratory exchange between Zimbabwe and South Africa is not a new one. Even before Apartheid-era restrictions on travel had ended and South Africa’s borders subsequently began to open, laborers were recruited to work the diamond and gold mines in northern South Africa (1). Today, Zimbabwean nationals residing in South Africa are estimated to number between three and five million (2). Public opinion among black and white South Africans describes these foreign nationals as a burden on the state infrastructure and as a competing force for those locals who are unable to find steady employment. Xenophobic sentiments within the general public have flared up on a number of occasions since, most notably in May of 2008 when some 62 people were killed and 670 wounded in violence that erupted in predominantly immigrant areas of the larger urban centers in South Africa. Large scale internal migration by foreigners fleeing the conflict occurred after these events, with an estimated 33,000 individuals being displaced (3). This understanding of “unwanted” immigration is set against a larger backdrop of political and economic uncertainty within Zimbabwe. While large-scale inflation and seizure of white-owned farms have rocked the country’s financial market the underlying issue of food security is becoming ever more relevant as climate change predictions show the quantity and frequency of rainfall becoming more erratic. Maize, the country’s primary source of nutritional value and livelihood, proves itself as ill adapted to water-scarce environments. Zimbabwe's historical past coupled with current short-sighted decision making has set the country up for increasing food scarcity. The logical path for many is to make the crossing to South Africa, yet the question remains: when will the neighbors next door roll up their proverbial welcome mat?

The Context of Xenophobia in South Africa

Accompanying the end of Apartheid, a new project of South African nation building was started. Many believe that in trying to create an inclusive identity for all South Africans, a harsh identity based on xenophobia and cultural superiority was formed instead (4). Rather than harmoniously containing the diverse ethnic groups that comprise South Africa's population and reversing the legacy of apartheid, a new segregated societal structure now positions black foreigners at the bottom of the social hierarchy where black South Africans were previously placed. Beginning in 1994, various domestic groups within South Africa vocalized a call for action that the new government would need to immediately address the issue of new immigrants flooding the country and free riding on a system of public resources. In addition to the so-called “stealing” of jobs, South African public opinion often dictates that foreigners from other parts of Africa are responsible for increased looting, rape, and other violent crime.

|

| Soweto, Gauteng - Scene of May 2008 Violence. Image Source: Patrick Egenhofer |

|

| Mitchell's Plain - Scene of May 2008 Violence. Image Source: Patrick Egenhofer |

Abbreviated Timeline of Recorded Xenophobia Against Zimbabweans (5, 6)

| YEAR | EVENT |

| 1994 | The IFP (Inthaka Freedom Party) warns of “physical action” if the ANC-led regime does not deal with issue of immigration. |

| 1994 | Gangs use violence in order to evict Zimbabweans and other Africans from Alexandra Township. |

| 1996 | Violence in an anti-foreigner campaign breaks out in Mizamoyethu, Cape Town. |

| 1996 | South Africa extends permanent residency to an estimated 124,000 non-nationals from SADC (South African Development Community) countries, including Zimbabwe. |

| 1997 | Joe Modise, Minister of Defense, alleges a correlation between undocumented migration and crime. |

| 1997 | A survey conducted by the Southern African Migration Project finds that few migrants actually wish to settle in South Africa. |

| 2001 | Hundreds of Zimbabweans are forced from their homes in Zandspruit. Houses are burnt down after word gets out that a Zimbabwean was accused of murdering a South African woman. |

| 2002 | A new Immigration Act is passed that alleges to fight xenophobia, yet lacks definition of how. |

| 2005 | Zimbabwean refugees are the subject of violence in Bothaville, Free State. |

| 2006 | Two Zimbabwean men are burned to death in Choba. |

| 2006 | Two Zimbabweans killed in Olievenhoutbosch. |

| 2008 | Two Zimbabweans beaten to death in Choba. |

| 2008 | Three Zimbabweans killed in Diepsloot. |

| 2011 | Two Zimbabweans killed in Diepsloot. |

Zimbabwe's Current Situation

The geography of Zimbabwe dictates that throughout the year, the one rainy season during the summer brings the country the majority of its annual rainfall. The south features a hotter and drier climate than the northern parts of the country, which lie at a higher altitude. Much of the arable farmland that is in use, however, can be found throughout the south-central portions of the country. Rainfall in these areas is often below 600mm per year. Within the last 20 years, Zimbabwe has experienced multiple droughts that cut the amount of rainfall to merely a third of what would be expected in the course of an average year (7).

Push Factors of Food Security

In Zimbabwe, recent events that have agitated the situation and pose a threat to regional stability can be linked to the Robert Mugabe-led Zanu-PF’s policies of seizing and redistributing large, predominantly white-owned commercial farms. Since their beginning in 2000, these farm seizures have caused domestic food production to nose-dive: production of maize fell from two million tons in 2000 to a mere 400,000 tons in 2010 (8). This land reform act had widespread effects on the migratory patterns of Zimbabweans: 92 percent of all recorded arrivals of migrants from Zimbabwe occurred after these began, demonstrating the fragility that accompanies land and food issues within Zimbabwe (9). Critics now blame much of the political instability found in the country on the loss of credibility and outrage that erupted in the aftermath of this implementation, siting widespread crop failure and a lack of experience by the farms’ new owners as evidence to prove Zimbabwe’s fragile food security situation. While a February, 2013 report stated that these reclaimed farms are now producing crops at their pre-seizure levels, critics from Zimbabwe's Commercial Farmers’ Union have disputed these claims as false and irrelevant given that food output in actuality did not even amount to two thirds of the government figure, and that Zimbabwe appealed to the United Nations for food aid for 1.6 million people—one tenth of its entire population (8).

While the centralized apparatus of the country’s food production was dealt a hard blow, much of the population turned to subsistence farming in order to maintain their livelihood. It is estimated that almost 70 percent of Zimbabweans are directly dependent on agriculture as a means of living, either through formal employment or subsistence farming (10). This past decade's increasing frequency of drought has led to Zimbabwe being a net-importer of food after having historically been known as the "Breadbasket of Africa (11)."

African Maize. Image source: Tom Rulkens, Wikipedia Commons |

|

Maize currently accounts for 70 percent of all calories consumed by humans within the region. The potential that rainfall may produce increasing strain on national food security is exacerbated by the fact that maize is a more water-intense crop when compared to the likes of millet or sorghum, which fare better in times of drought, both of which are compatible with Zimbabwe’s growing climate (12, 13).

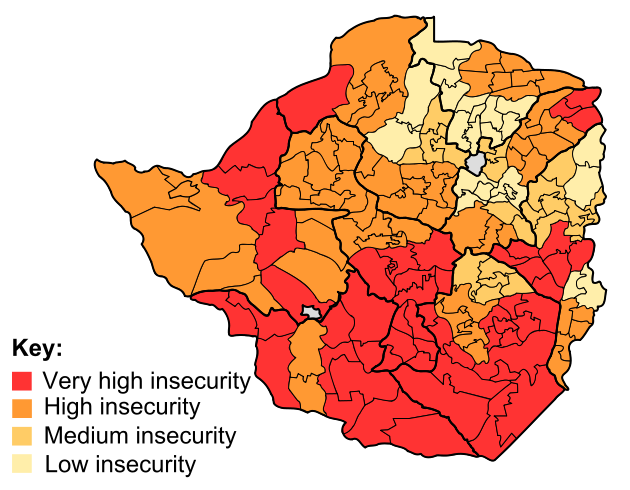

While regions in southern Zimbabwe that historically have had to cope with drought do grow millet and sorghum, food security has already been compromised as a result as can be seen in the figure below.

|

| Fig. 1.1: Current food security levels in Zimbabwe, by District. Southern Districts bordering South Africa already experience "very high insecurity." Wikipedia Commons. |

Push Factors of Public Health

The process of globalization has exacerbated push factors such as extreme poverty, hyperinflation, drought, and famine, making the pull factors’ promises of higher wages, more opportunity, political calm, and a perceivably "porous" border, all that more allusive (11). While in the early years of the upswing in undocumented migration, the majority of migrants were noted to be coming from the drought-prone and poorer districts of southern Zimbabwe, that trend has now waned and officials say that all parts of Zimbabwe now see people leaving to seek opportunities in South Africa (15). In showing the environmental fragility that currently is felt in the region, a cholera outbreak in 2008 killed an estimated 4,300 people died and a further 100,000 were determined to be affected by the disease (14). Shortages of potable water were exacerbated by failures in infrastructure and served as a large push-factor for many to opt for migration to South Africa. Future uncertainty over rainfall and predicted prolonged periods of drought have the possibility to cause more damage in terms of public health and drive more people to seek the stability of South Africa's social and economic infrastructure.

The Migration Process

The historical precedents of migration between Zimbabwe and South Africa are key to understanding the potential for increased migration in a future of uncertain climate development. Migration patterns are not the product of random paths of mobility, but rather largely the product of proximity, history, and ethnic or linguistic affinity. In regions that tend to produce the largest number of migrants to South Africa--predominantly Districts in the southern Zimbabwean region of Matabeleland South--kinship lines run across the international border as evidenced in the linguistic borders of the area. Ndebele, Vende, and Shona are spoken throughout this geographic area (15). In proving just how ingrained the idea of Zimbabweans temporarily leaving to find work in South Africa, an estimated one out of every Zimbabwean adults has moved across the border in search of better livelihood (13). With each of these movements come interpersonal ties that are made, either fostering a positive relationship that can be maintained, or sending a signal of for others to avoid certain individuals or communities should the connection not be fruitful. Zimbabwean migration to South Africa is based on this network of ties that serve as geographical markers for where success may be had thanks to the already established successes of a predecessor. Finding work in South Africa as a whole has proven itself as a close and relatively practical option for many Zimbabweans.

Undocumented migration of Zimbabweans has been individuals have sited the economic pressures they faced as a reason for why travel was not conducted in accordance to the law. With the introduction of a 2009 agreement between South Africa and Zimbabwe, visa restrictions for travel were dropped. Zimbabweans must confirm a letter of invitation from a South African resident, prove financial savings of 2000 Rand (Approx. 225 USD) and subsequently have 90-days within the country to obtain a full work permit (16). Still, the migratory system lacks regulation and mechanisms by which to track those who legally enter yet overstay this restriction, a major critique for some within South Africa. For a large portion of Zimbabwe's migratory population, legal entry is still not an option as they lack the ability to pay the price for acquiring a passport.

Figure 1.3, below, shows the route from Zimbabwe's major population centers, Harare, Bulawayo, and Gweru across the border--depicted in blue--at Beidtbridge and Messina, to the major destinations of Zimbabwean migrants Johannesburg (incl. Pretoria, Soweto, and nearby towns and settlements), Durban, and Cape Town. The District of Matabeleland South, near Bulawayo and on the international border to South Africa, has been the predominant place of origin for migrants, but major population centers remain the key source of migrant laborers due predominantly to the established networks of transportation that derive from there. At present, there is no longer a typical point of origin as Districts from all over Zimbabwe have experienced significant migratory leave to South Africa. While the easing of visa restrictions has allowed more legal migration to take place, individuals from Zimbabwe still opt to cross the Limpopo River as undocumented migrants due to the often shallow waters and lacking border controls. Even individuals who have the financial means to cross through the official border control at Beidtbridge have been noted to opt for clandestine migration due to the long wait times associated with South African immigration (15)

|

The fall of the Apartheid regime and the introduction of the new ANC-led government in 1994 marked the start of a new era of policymaking for issues dealing with immigration in South Africa. Since then, periodic upswings in violence have been experienced due to the failure of ruling administrations to effectively deal with the perceived threat posed both by documented and undocumented non-nationals.

Continent: Africa

Region: Southern Africa

State: South Africa

Violence occurs in urban centers outside Cape Town, Johannesburg, Durban, and Pretoria, as well as smaller communities throughout South Africa and towns in close proximity to the international border with Zimbabwe.

Due to the civilian and largely decentralized nature of the conflict at hand, there are no substantial or widely-recognized actors responsible for the violence that has been noted. Each of the following groups has played an indirect role in the conflict up until now, either drumming up support for or indeed dispelling xenophobic tendencies within the general public--some have been accused of doing both.

The African National Congress (ANC): South Africa's largest and ruling political party, is responsible for the post-apartheid restructuring of the country. While violence and xenophobia has been officially condemned, certain officials within the party have been accused of complacency and not doing enough to curb xenophobic violence, as well as inciting xenophobic sentiments within their local communities (17).

"The xenophobic sentiments evident in parts of South Africa runs against the current of the country's main political traditions, and is in sharp conflict with the strong non-racial culture of the majority of its people."

- ANC Today, August 2001(18).

Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP): A Zulu-based political group with strongholds in the South African state of KwaZulu-Natal. During the early post-apartheid days, this group was among the first to voice its concern to the public about the rising rates of immigration from neighboring states. It threatened with physical violence if the ANC-led government did not take control of the situation and curb entry rates. Official party views, however, reflect a more nuanced rhetoric in light of the killings in 2008.

"The IFP believes that there are other ways of raising concerns by communities into socioeconomic issues."

- Mr. VB Ndlovu, IFP Spokesperson, in response to the IFP's stance on xenophobia. September 2012 (19).

South African Blacks Association (Saba): An underground group lacking official recognition and of disputed size and credibility that has been noted for its xenophobic and ethnocentric public comments towards black non-South Africans. The involvement of this group demonstrates the decentralized and clandestine, yet publicly vocal nature that is representative of the hardline anti-foreigner movement within South Africa.

"We will burn your houses, your so-called luxury cars, we will kill your fucken [sic] puppies [children] and burn down your shops."

- Publicly distributed pamphlet, September 2012 (20).

South African Police Service (SAPS): The national police service of South Africa. Accounts of widespread discrimination against foreign nationals have surfaced in recent years. Officers of SAPS have been accused of unlawful imprisonment based on racial profiling, unlawful prolonged detention for non-nationals, unnecessary brutal force being inflicted on those believed to be non-nationals, not assisting non-nationals under threat of violence, and inhumane treatment of prisoners believed to be from other countries (2).

Government of the Republic of Zimbabwe: Far removed from the cycle of xenophobic, domestic violence in South Africa, the state of Zimbabwe and the joint Zanu-PF and Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) coalition government remains an active participant in the root-cause of the conflict due to its role in failing to address the effects of climate change on food and job security.

“Increases in global temperatures are associated with undesirable climate change impacts, and devastating droughts, floods and storms seen in Zimbabwe and across the world in recent years show how vulnerable we are to climate extremes and how high the economic, human and environmental costs can be particularly in developing countries."

- Florence Nhekairo, Secretary in the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources Management, April 2013 (21).

Source problems: Water shortage

Zimbabwe’s Prospects for Climate Change

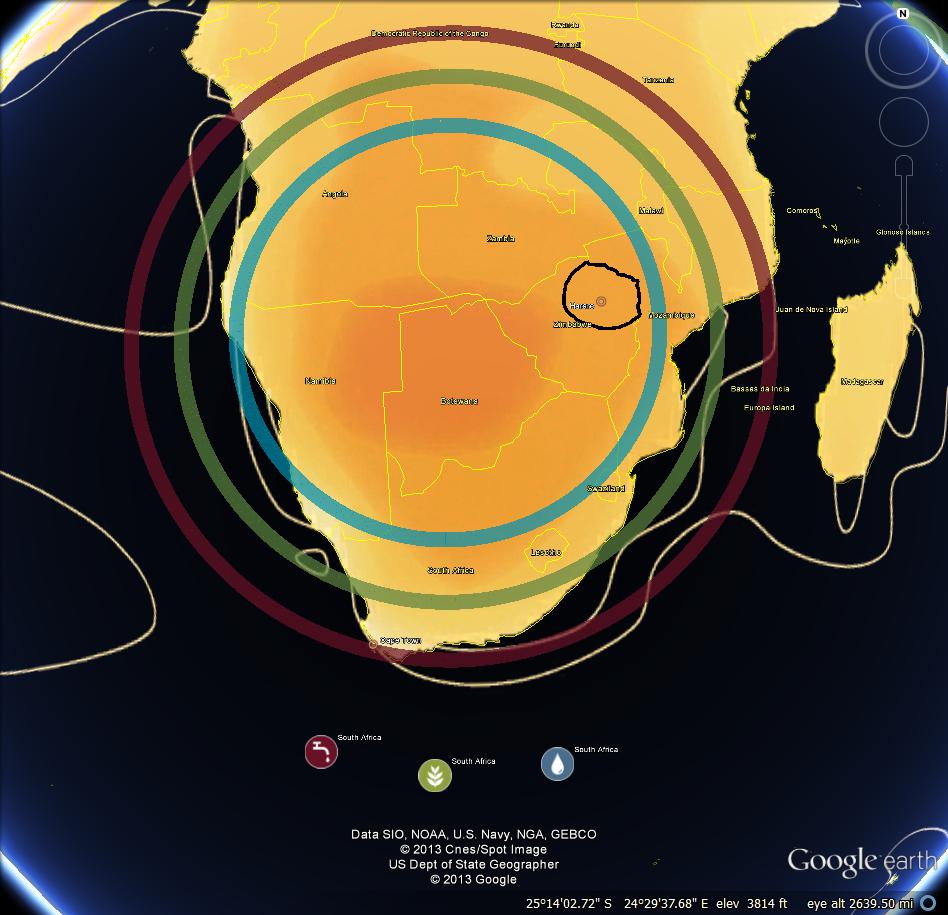

Zimbabwe is currently listed as one of the ten-most vulnerable countries in the world in terms of its exposure to natural hazards and poverty-related resilience to overcome such these hazards (22). As noted in a 2011 report by the Migration Policy Institute, disruption of the hydrological cycle may be caused by increasingly common dry spells that have the ability to impede the typical agricultural seasons (26). Figure 1.1 depicts a modeled a 4º Celsius rise in temperature. Zimbabwe’s entire landmass falls within an area predicted to experience decreased water availability (red ring), increased crop failure (green ring), and decreased annual rainfall (blue ring). The area outlined in black marks the region where the vast majority of the country's maize--Zimbabwe's most important crop--is grown (13).

|

While experts have warned that a climate prediction model for the region of Southern Africa cannot be complete without an understanding of the El Niño and La Niña effects which dictate much of the variability in the levels of annual rainfall, variability and drought have always been a factor in this area's climate (13, 28). In the past century, Zimbabwe has seen average temperature increases of approximately 0.8ºC, and average annual rainfall decline by approximately 10 percent (7).

Although the central government in Harare has been placing pressure on subsistence farmers to produce more in order to reduce its dependency on expensive food purchases from abroad, farmers lack the ability to predict increasingly erratic rainfall patterns--especially given the great deal of emphasis placed on traditional knowledge of seasonal and weather patterns. In late 2012, weather changes that imply imminent rains triggered farmers to begin their typical crop planting. The rains did not come until February and March of 2013. Government meteorological offices have been called out for their inability to predict weather patterns. But adding a further dimension alongside this, even the best government planning could not allocate resources and regulate growing effectively within this volatile system of agricultural production given the fact that there is a disconnect between the scientific knowledge the government holds and is able to distribute, and the fact that farmers ignore this advice and continue to rely on traditional knowledge of when to begin their planting seasons (11, 23).

Zimbabwe's geography features many high-altitude plateaus and therefore experiences a generally temperate climate despite being located in the tropics. Cool winters run from May to August, while hot summers run from December to February. A single rainy season, running from November through to March is responsible for the majority of the country's annual rainfall (7).

Within the context of conflict, the act sight is the physical place where the root cause of the problem stems from. The harm sight is found where the consequences of that action are experienced. Within the framework of this analysis of xenophobic violence against ecological migrants from Zimbabwe in South Africa, the main conflict act site can be found throughout the north eastern quadrant of Zimbabwe, where the corn-growing region that feeds and sustains most of the country can be found. The harm sites are found throughout populated areas of South Africa where any number of South Africans and Zimbabweans may be living in close proximity. Urban centers and their outer townships, refugee camps, and towns in close proximity to the international border have all experienced periodic bursts of violence, yet single acts have been reported throughout the country.

The conflict, at present, has not manifested itself on an international level. Though the situation has been discussed by public officials in both Zimbabwe and South Africa, international action on the state-level is not expected considering the close relationship the two leading regimes enjoy. The conflict is expected to remain civilian in nature and will not rise to involve any state-sanctioned foundation or organization due to the official stance that the government of South Africa has taken on the matter based on the provisions of protection of human life and equality mandated by the post-apartheid constitution. Reported attacks have been instigated by groups or individual South Africans that have either rallied to vocalize their loss of livelihood and the inaccessibility of work or acted based on such frustrations. These groups target individuals who are or indeed "look like" foreigners from neighboring countries and--more recently--the institutions associated with the success of nationals of neighboring countries. Though this conflict involves groups who happen to be from different countries, the conflict takes place in a purely domestic space and has not led to any repercussions or retaliatory acts of violence back in Zimbabwe.

Though the conflict exhibits a notably brutal tendency when manifested in public acts of violence, examples such as these acts do not dominate the everyday interactions between South African and Zimbabwean groups. Reports and interviews provide insight into constant tensions between these groups, namely in the form of "softer" and more structurally-based violence, i.e. in the form of Zimbabweans being denied medical service, experiencing public verbal abuse, and having their property destroyed by South Africans. Still, violent acts serve as outliers in this trend and the conflict level remains low.

To date, there are no military fatalities that are associated with this conflict. Deaths are estimated due to the decentralized nature of the conflict as well as the lack of official statistical data on the subject matter. It is important to note that xenophobic violence affects not only Zimbabwean migrants within South Africa, but individuals from other African nations as well. While this case study may be based upon Zimbabwe’s unique environmental progression, the potential migrants from such a scenario would be indiscriminate from those who currently experience xenophobic violence due to distinctly South African social constructions of race and tribe. Therefore, this case evaluates the level of conflict based upon estimates of the average death counts from xenophobic violence within South Africa, regardless of the victim's place of origin within Africa. Figure 1.1, below, denotes the total and average number of deaths based on estimates made in reports that count violent conflict in terms of recorded deaths and public calls for action made by communities who claim to have experienced a certain minimum number of casualties. At the same time, these figures do not take into account those individuals who have attempted the crossing from Zimbabwe to South Africa as undocumented immigrants but lost their life in transit.

Figure 1.1 (5):

Total # of deaths 1994 - Present (EST.) |

130 - 1000 |

| Average # of deaths per year (EST.) | 7 - 53 |

Definitions of Level of Conflict in terms of Death per Year:

1(1) = 1

1(2) = 10

1(3) = 100

1(4) = 1,000

1(5) = 10,000

1(6) = 100,000

1(7) = 1,000,000

1(8) = 10,000,000

1(9) = 100,000,000

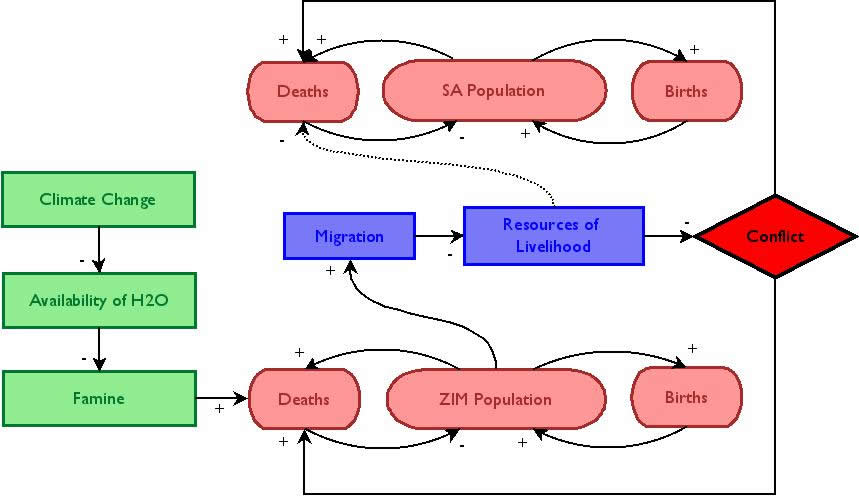

Figure 1.2 is a causal-loop diagram that demonstrates the cyclical nature of the conflict in terms of the effects climate change will have. As a direct effect, annual rainfall levels become less predictable and increasingly erratic. Given this, the probability of famine increases as the regularity in annual rainfall diminishes, as demonstrated by the plunge in annual rainfall during the El Niño years 1983 and 1992 which produced widespread famine in Zimbabwe (24). As the consequences of famine intensify, the potential risk involved in migrating becomes more viable, and in turn, resources including jobs, available land, food availability, water access, and housing may all be subjected to higher levels of scarcity. In large parts of South Africa, the allocation of these resources is already the subject of much debate following post-Apartheid efforts at redistribution. Increased demand by non-nationals can become both a perceived or indeed real threat to livelihood and life itself within the South African life cycle. Increased violent crime, burglary, access to medical care, and allocation of housing have all been noted as potentially harmful issues related to resource scarcity for native South Africans. Conflict ensues and deaths on both sides of the issue are seen.

Figure 1.2:

|

On a number of levels, the development of this case proves itself as being of strategic interest. At the sub-state level, communities facing the violent outbursts against non-national migrants have a vested interest in preventing any further conflict from occurring, while at the same time maintaining fair and equitable distributions of public goods. At the state level, the South African government faces increased rates of violent crime should it fail to act in dampening xenophobic public sentiment within the domestic setting. At the regional level, South African officials have a vested interest in preventing future Zimbabwean famines which could create the potential for increased attempts of undocumented migration and feed further into the cycle of xenophobic violence as the public's answer resource and employment shortages.

Conflict between South African and Zimbabwean individuals remains an on-going issue given new cases of violence, joblessness, and perceived encroachment onto personal property being blamed upon the issue of increasing immigration. As such, official parties involved claim no involvement in these cases of violence and dissuade factions from resorting to conflict. This case study argues that the future potential for civil conflict is inversely correlated to the internal balance of well-being within Zimbabwe.

The Zimbabwean government lacks the ability to invest in necessary infrastructure that would mitigate the burden that climate change will present for food security issues. As such, crops will continue to be fed by increasingly erratic and irregular rainfall. With agriculture being such a key factor in the wellbeing of Zimbabwe's population, more and more people will inevitably try to make the journey across the Limpopo River to South Africa, where livelihoods are still able to be maintained. Subsequently, as people either move to South Africa with the intention of taking up permanent residency or to supplement the family's income back home with sent remittances, xenophobic tendencies that have pervaded in South African society since the end of apartheid will provide a backlash against these non-nationals for their contributing to scarce local resources. Without government intervention in the form of public education by South African officials, discrimination and violence against non-national migrants will be perpetuated through the cyclical arrival of new coming outsiders.

15. Related ICE Cases

Flag Images Sourced from Wikipedia Commons

1. Mafukidze, Jonathan. “A Discussion of Migration and Migration Patterns and Flows in Africa.” Views on Migration in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2006.

2. " How many Zimbabweans in SA?." News 24. South African Press Association, 23 Jun 2009. Web. 13 March 2013.

3. "TOLERATING INTOLERANCE: XENOPHOBIC VIOLENCE IN SOUTH AFRICA ."CITIZENSHIP RIGHTS IN AFRICA INITIATIVE. CITIZENSHIP RIGHTS IN AFRICA INITIATIVE (CRAI) , n.d. Web. 13 March 2013.

4: "SOUTH AFRICA: Act II of xenophobia waiting in the wings." IRIN News. IRIN, 12 Mar 2009. Web. 12 March 2013.

5. Khumalo-Seegelken, Ben. "XENOPHOBIA TIMELINE."Ben Khumalo Seegelken. N.p.. Web. 23 April 2013.

6. McVeigh, Tracy. "South Africa fears new wave of violence against foreigners." Guardian UK. The Observer, 4 Jun 2011. Web. 9 March 2013.

7. McSweeney, Robert. "Zimbabwe: Climate Change Profile."Tearfund. Tearfund, n.d. Web. 12 March 2013.

8. Mwando, Madalitso. "Zimbabwe eyes food security amid drought." Al Jazeera English. Al Jazeera, 16 Apr 2013. Web. 4 May 2013.

9. Mosala, Simona M Gallo. “The Work Experience of Zimbabwean Migrants in South Africa.” ILO Sub-Regional Office for Southern Africa. September 2008. Accessed 2 March 2013.

10. Tekere, Moses. "Zimbabwe." Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, n.d. Web. 15 March 2013.

11. Kuwuya, Kumbirai. "Drought and Famine in Zimbabwe Expected Again this Year." Future Directions International. Future Directions International, 26 Apr 2012. Web. 14 April 2013.

12. Martin, Randall, Richard Washington, and Thomas Downing. "Seasonal Maize Forecasting for South Africa and Zimbabwe Derived from an Agroclimatological Model." American Meteorological Society. JOURNAL OF APPLIED METEOROLOGY, n.d. Web. 12 April 2013.

13. Maphosa, France. "THE IMPACT OF REMITTANCES FROM ZIMBABWEANS WORKING IN SOUTH AFRICA ON RURAL LIVELIHOODS IN THE SOUTHERN DISTRICTS OF ZIMBABWE." The Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA). The Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA), n.d. Web. 15 April 2013.

14. "100,000 cases The spectre of cholera remains in Zimbabwe." Australian Red Cross. IFRC Communications Department, n.d. Web. 21 April 2013.

15. Monson, Tamlyn. "Zimbabwean Migration into Southern Africa: New Trends and Responses." Academia. Forced Migration Studies Programme, University of Witwatersrand. Web. 29 April 2013.

16. Mawadza, Aquilina. "The nexus between migration and human security Zimbabwean migrants in South Africa." Institute for Security Studies. Institute for Security Studies, n.d. Web. 21 April 2013.

17. Rawoot, Ilham. "ANC dithers on xenophobia." Mail and Guardian. Mail and Guardian, 24 Jun 2011. Web. 21 April 2013.

18. "ANC POLICY ON XENOPHOBIA." Queens University. ANC Today, n.d. Web. 1 April 2013.

19. "IFP: Statement by VB Ndlovu, Inkatha Freedom Party Spokesperson on Police, calls on urgent investigation into Xenophobia claims in Johannesburg (11/09/2012)." Polity. Creamer Media, 11 Sep 2012. Web. 1 April 2013.

20. Parker, Faranaaz. "http://mg.co.za/article/2012-09-03-xenophobia-rears-its-head-in-mayfair." Mail and Guardian. Mail and Guardian, 03 Sep 2012. Web. April 3 2013.

21. Langa, Veneranda. "Climate change to take its toll on Zim."Newsday. Newsday Zimbabwe, 13 Apr 2013. Web. 13 April 2013.

22. Newland, Kathleen. "Climate Change and Migration Dynamics." Migration Policy Institute. The European Union, n.d. Web. 4 May 2013.

23. Mwando, Madalitso. "Zimbabwe farmers struggle to determine right planting time." TRUST. Thomson Reuters Foundation, 9 Nov 2011. Web. 19 April 2013.

24. Fagan, Brian. Floods, Famines, and Emperors. New York: Basic Books, 1999. Web.