Cattle in Jonglei, South Sudan. Source: Oxfam

1.1 Abstract

Cattle

raids in South Sudan have been a source of communal violence for

decades, if not centuries. In pastoral communities cattle are an

indicator of social standing and wealth, often used in restorative

justice and marriage practices. The act of cattle raiding in of it

self demonstrates a male youth's transition from adolescent to

maturity. Subsequently, the significance of cattle to Sudan's Nilotic

peoples has historically placed them at the centre of confrontations

between communities. In Jonglei state of South Sudan patterns of

pastoralist migration are driven by seasonal environmental changes.

During the dry seasons communities living in more arid regions herd

their cattle towards areas with more abundant toiche (marsh fed pasture)

and water resources. As a result communities already positioned in

adversarial relationships are brought into closer proximity and become

engaged in conflicts over access to these essential resources. Over the

past five years the frequency and intensity of these clashes has

escalated significantly. Catalyzed by insecurity and the legacy of a

civil war spanning three decades, the conflicts associated with

seasonal migrations in South Sudan have reached such an intensity as to

be described as "Pastoral Wars." Large infrequent raids, coupled with

repeated small-scale incidents, have fostered conditions of insecurity

and entrenched poverty. At the same time the Horn of Africa has been

blighted by severe drought that is prolonging the dry season,

increasing the necessity of migration and reducing the abundance of

contested resources. In this case study climate change is best

understood as a conflict multiplier, exacerbating the factors of

environmental degredation that drive on-going patterns of violence.

Cattle

raids in South Sudan have been a source of communal violence for

decades, if not centuries. In pastoral communities cattle are an

indicator of social standing and wealth, often used in restorative

justice and marriage practices. The act of cattle raiding in of it

self demonstrates a male youth's transition from adolescent to

maturity. Subsequently, the significance of cattle to Sudan's Nilotic

peoples has historically placed them at the centre of confrontations

between communities. In Jonglei state of South Sudan patterns of

pastoralist migration are driven by seasonal environmental changes.

During the dry seasons communities living in more arid regions herd

their cattle towards areas with more abundant toiche (marsh fed pasture)

and water resources. As a result communities already positioned in

adversarial relationships are brought into closer proximity and become

engaged in conflicts over access to these essential resources. Over the

past five years the frequency and intensity of these clashes has

escalated significantly. Catalyzed by insecurity and the legacy of a

civil war spanning three decades, the conflicts associated with

seasonal migrations in South Sudan have reached such an intensity as to

be described as "Pastoral Wars." Large infrequent raids, coupled with

repeated small-scale incidents, have fostered conditions of insecurity

and entrenched poverty. At the same time the Horn of Africa has been

blighted by severe drought that is prolonging the dry season,

increasing the necessity of migration and reducing the abundance of

contested resources. In this case study climate change is best

understood as a conflict multiplier, exacerbating the factors of

environmental degredation that drive on-going patterns of violence.

1.2 - Description

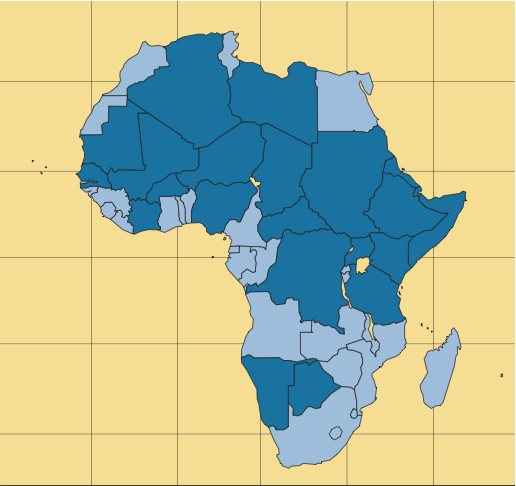

Pastoral

communities (marked in dark blue) can be found in over twenty one

countries in Africa, spanning from the Sahel in the West, to the Horn

of Africa in the East, and as far as Namibia in the South (SAS 2007).

They are concentrated in some of the most arid regions of the

continent, areas that are likely to be hardest hit by the impacts of

global climate change. Pastoralism is defined as, "the finely-honed,

symbiotic relationship between local ecology, domesticated livestock

and people in resource-scarce areas €“ often at the threshold of human

survival" (Pratt, Gall and Haan 1997). In the

development-security agenda African pastoral communities have become

synonymous with high levels of armed violence and severe

under-development (SAS 2007), but little attention is focused on the

environmental dynamics in these conflict prone societies. The example of

Jonglei state in South Sudan can be seen asrepresentative of a far

broader pattern of the convergence of climate change, poverty and

insecurity.

Pastoral

communities (marked in dark blue) can be found in over twenty one

countries in Africa, spanning from the Sahel in the West, to the Horn

of Africa in the East, and as far as Namibia in the South (SAS 2007).

They are concentrated in some of the most arid regions of the

continent, areas that are likely to be hardest hit by the impacts of

global climate change. Pastoralism is defined as, "the finely-honed,

symbiotic relationship between local ecology, domesticated livestock

and people in resource-scarce areas €“ often at the threshold of human

survival" (Pratt, Gall and Haan 1997). In the

development-security agenda African pastoral communities have become

synonymous with high levels of armed violence and severe

under-development (SAS 2007), but little attention is focused on the

environmental dynamics in these conflict prone societies. The example of

Jonglei state in South Sudan can be seen asrepresentative of a far

broader pattern of the convergence of climate change, poverty and

insecurity.

After two civil wars (1955 - 1972 and 1983 - 2005), the citizens of the Republic of South Sudan brought their country into existence through a referendum on its secession from the Sudanese state in January 2011 (BBC 2011). Although the conflict has been generalized by the secession of the Sudan People's Liberation Movement / Army (SPLM/A) from the central government of Sudan in Khartoum, it was underpinned by a complex web of tribal alliances. Incredible human suffering was endured over more than forty years of violence, an estimated 2 million people died and 6 million people were displaced during the conflicts (UNICEF 2008). South Sudan now faces the challenge of a near absence of social and economic development; with few exceptions the country's entire infrastructure has either been destroyed or severely damaged (UNICEF 2008). The vast majority of the country's citizens live in extreme poverty, existing on livelihoods that meet only the most basic requirements of human survival.

An estimated 1.7 million people in Southern Sudan have been food insecure in the last ten years, the majority (up to 40 percent) from Jonglei, Northern Bahr el-Ghazal and Upper Nile states (FAO 2010). Jonglei is chronically deprived of social and economic development, leaving the local population on the threshold of extreme poverty. The main livelihood systems in the state are agropastoralism, pastoralism and fishing. A spate of droughts and subsequent crop failures has left Jonglei in a condition of acute food and livelihood crisis since 2008. Some 39 percent of the population is food insecure and 30 percent severely food insecure, whilst the global acute malnutrition (GAM) rate is reported at 21.4 percent (FAO 2010). This year South Sudan is expected to produce half the crops required to meet food security (Guardian 2011). Food insecurity is mainly related to conflict over natural resources and cattle raiding, the influx of returnees, floods and drought (FAO 2010). The inhabitants of Jonglei are caught in a poverty trap, dependent on livelihoods that are vulnerable to environmental shifts and drive violent conflict.

Due to the limited resources and income generating livelihoods most residents of Jonglei live semi-nomadic life styles, herding cattle in concert with seasonal changes to the environment. With limited access to water and competing rights to land, inter-tribal conflict arises when pastoralists from one tribe enter the territory of another (Leff 2009). Conflicts between farmers and cattle-keepers are a recurring problem towards the end of dry season, when cattle are taken to graze on planted fields. Clashes are also reported at water sources, where cattle-keepers and fishermen compete for the best spots (LSE 2011). Worsening droughts are forcing inhabitants of South Sudan to expand their geographic range at the expense of the environment (UNICEF 2008). Environmental changes caused by climate change are increasing the necessity of migration and reducing the availability of contested resources. In turn this increases both the frequency that communities with long standing enmities come into contact with each other, and the value placed upon diminishing resources.

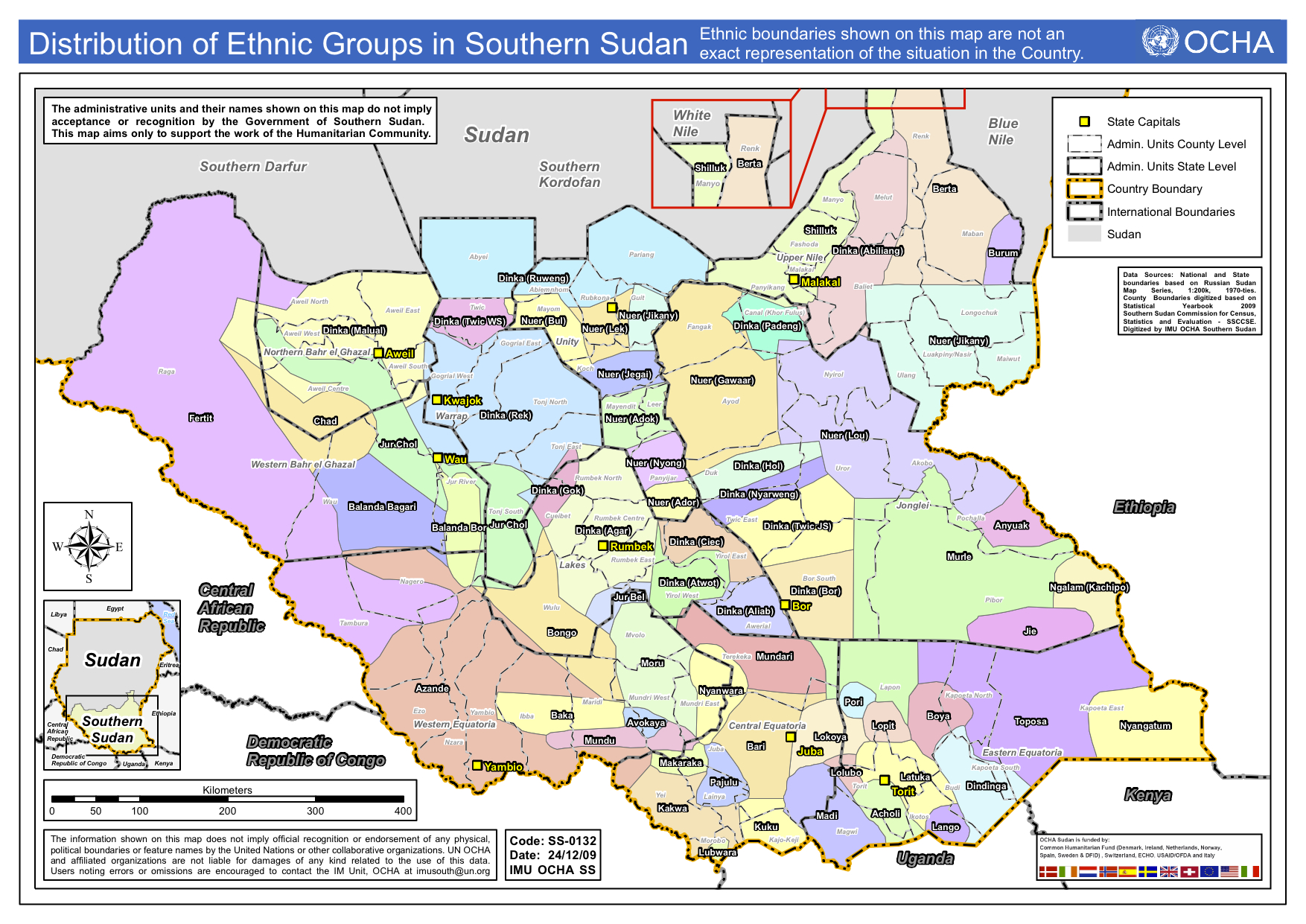

Tribal

conflict in Southern Sudan, particularly among pastoralist

communities, such as those in Jonglei (marked in red), is by no means a

new phenomenon. Cattle raiding and reprisals have been a part of life

for generations between the Nuer, Dinka and Murle tribes. Raids

undertaken to increase stocks, and compensate for those lost to

pestilence and thefts have been normalised and accepted as part of

traditional inter-communal relations (ICG 2009). However, over the past

five years the intensity of violence has become intensified in terms

of both scale and frequency. In 2005 the Comprehensive Peace Agreement

(CPA) finally brought the second Sudanese Civil War to an end.

Paradoxically, for many the CPA created a security vacuum that can now

be seen as a key-contributing factor to the violence in Jonglei.

Tribal

conflict in Southern Sudan, particularly among pastoralist

communities, such as those in Jonglei (marked in red), is by no means a

new phenomenon. Cattle raiding and reprisals have been a part of life

for generations between the Nuer, Dinka and Murle tribes. Raids

undertaken to increase stocks, and compensate for those lost to

pestilence and thefts have been normalised and accepted as part of

traditional inter-communal relations (ICG 2009). However, over the past

five years the intensity of violence has become intensified in terms

of both scale and frequency. In 2005 the Comprehensive Peace Agreement

(CPA) finally brought the second Sudanese Civil War to an end.

Paradoxically, for many the CPA created a security vacuum that can now

be seen as a key-contributing factor to the violence in Jonglei.

First, the SPLA had maintained a relative degree of order, which disappeared when - in line with the CPA - they were transitioned from a guerrilla force to a formal standing army but civilian policing did not replace their deterence role at the local level (ICG 2009). Without acceptable forms of non-violent dispute resolution or security agents to prevent criminal activity cattle raiding has entrapped these communities in a feed back loop of vengeance.

Second, the civil war inundated South Sudan with small arms and light weapons (SALW), the CPA failed to provide an effective mechanism for the equitable disarming of the civilian populous (SAS, 2007b). Automatic weapons have had a catalytic effect on violence in Jonglei, by replacing traditional weapons such as spears and machetes SALW have exponentially increased the lethality of pastoral conflict (2007b). Cattle-raiders are often better armed than the police or even the army, posing a direct threat to the rule of law. Furthermore, modern weapons also make fatalities much more likely than in the past and limit the possibilities of using traditional mediation or compensatory measures to contain the violence (LSE 2011). In this "post-conflict" context cattle raiding has risen dramatically in terms of both scale and lethality.

Cattle raiding in Jonglei takes place against the back drop of a complex political environment. In the midst of the second Sudanese Civil War Dr Riek Macher, and his Lou Nuer allies, revolted against Dr. John Garang's SPLM/A and formed a splinter group - the South Sudan Defence Force. During the late 1990 €™s Dr. Macher was backed by the government of Sudan, but eventually rejoined the SPLM/A and rebranded his militia as the Sudanese People's Democratic Forces (Evoy & LeBrun, 2010). Although Dr. Macher as an individual was reconciled with the political elite in Juba, the Lou Nuer's treachery provides a strong political motivation for conflict between Jonglei's tribal communities (ISS 2010).

The

origins of the current pattern of violence associated with pastoral

migration and tribal militia in Jonglei can be pin pointed to a

coercive disarmament campaign conducted by the SPLA between December

2005 and May 2006 (Evoy & LeBrun, 2010). The campaign was initiated

at the request of Dinka communities that host Lou Nuer cattle hearders

during the dry season (SAS, 2007a). The Lou do not have sufficient

grazing lands and water within their own territory during the dry

season and as a result must move their cattle into the lands of their

neighbours (ISS 2010). The Nuer refused, arguing that the campaign

would affect them unequally in comparisson to the other tribes in

Jonglie, and that they required their weapons to defend themselves

against the Murle tribe. Negotiations broke down and the Lou Nuer's

White Army militia and the SPLA engaged in skirmishes that escalated to

major battles. When violence ceased in May 2006 3,300 weapons had been

confiscated by the SPLA, but 1,200 members of the White Army and 400

members of the SPLA were killed in the process (SAS, 2007a).

The

origins of the current pattern of violence associated with pastoral

migration and tribal militia in Jonglei can be pin pointed to a

coercive disarmament campaign conducted by the SPLA between December

2005 and May 2006 (Evoy & LeBrun, 2010). The campaign was initiated

at the request of Dinka communities that host Lou Nuer cattle hearders

during the dry season (SAS, 2007a). The Lou do not have sufficient

grazing lands and water within their own territory during the dry

season and as a result must move their cattle into the lands of their

neighbours (ISS 2010). The Nuer refused, arguing that the campaign

would affect them unequally in comparisson to the other tribes in

Jonglie, and that they required their weapons to defend themselves

against the Murle tribe. Negotiations broke down and the Lou Nuer's

White Army militia and the SPLA engaged in skirmishes that escalated to

major battles. When violence ceased in May 2006 3,300 weapons had been

confiscated by the SPLA, but 1,200 members of the White Army and 400

members of the SPLA were killed in the process (SAS, 2007a).

As predicted by the Lou, the disarmament campaign left them vulnerable to predication from neighboring Dinka and Murle cattle raiders. Over the next eighteen months the Lou Nuer re-armed, leading to an escalating series of skirmishes that culminated in Dinka raiders stealing 20,000 Lou Nuer cattle (ICG, 2009). During this period the characteristics of violence associated with cattle raiding changed dramatically, from actions by a small number of raiders that resulted in few deaths to massacres committed by organized militia. In March 2009 an attack by a Lou Nuer militia on seventeen Murle settlements resulted in the deaths of 453 people. Within a week the Murle retaliated with a raid that killed 250 members of the Lou Nuer community. These clashes set in motion a spiral of violence that killed more than 2,500 people in 2009, a greater number of fatalities than in Darfur during the same year (OCHA, 2009).

Despite several further

attempts at coercive disarmament and conflict resolution acts of

violence once again spiraled began to spiral in February 2011 and

peaked in the summer months. On June 15 2011 an attack by the Lou Nuer,

possibly aided by members of Dinka tribes, left 400 members of the

Murle community dead. The Murle retaliated on August 18 2011, killing

640 people, destroying almost 8,000 homes, stealing 38,000 cattle, and

attacking a Medecins Sans Frontier hospital. In this latest series of

clashes the United Nations estimates that approximately 26,000 cattle

were stolen. The violence has now reached such a level as to receive

attention from United Nations' Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon who

denounced the violence and demanded the government of South Sudan take

action to restore security (UN, 2011b). The United Nations recently

announced that it would send peacekeepers and civilian personnel to

deter violence in the state (UN, 2011a).

However, without continued efforts to provide

security or nurture social and economic development any gains made were

shortlived. Writing in 2007 a leading think-tank on SALW commented,

"Disarmament alone is likely to produce only short- term gains,

especially when promised state security is not provided during and after

the campaign, or when disarmament proceeds without systematic efforts

to address the root causes of conflict" (SAS, 2007b).

1.3 - Duration

Cattle raids in South Sudan have been a source of communal violence for decades, if not centuries. However, in 2005 the Comprehensive Peace Agreement unintentionally created a power vacuum in South Sudan that has enabled a significant escalation of these conflicts. Within this post-conflict context the nature of cattle raiding has transformed from small scale to collective violence. Attacks now result in the massacre of hundreds of people, the razing of entire communities, and the destructions or theft of cattle and crops. Not only is there no end in sight for this violence, but it also appears to be increasing in frequency and intensity.

1.4 - Location

The

Republic of South Sudan can be found nestled between the Horn of

Africa, the Great Lakes Region, and the Sahel. A contiguous land locked

state of 619,745 square kilometres South Sudan shares boarders with

Sudan to the north, Ethiopia to the east, Uganda and Kenya to the

southeast, Democratic Republic of Congo to the southwest and Central

African Republic to the west (GoSS, 2011). The site of this case study

is Jonglei, one of ten states within South Sudan, which in turn is

divided into eleven counties that vaguely reflect tribal affiliations.

Although the world's youngest sovereign state South Sudan contains a

collection of communities that have contested their communal boundaries

for generations.

The

Republic of South Sudan can be found nestled between the Horn of

Africa, the Great Lakes Region, and the Sahel. A contiguous land locked

state of 619,745 square kilometres South Sudan shares boarders with

Sudan to the north, Ethiopia to the east, Uganda and Kenya to the

southeast, Democratic Republic of Congo to the southwest and Central

African Republic to the west (GoSS, 2011). The site of this case study

is Jonglei, one of ten states within South Sudan, which in turn is

divided into eleven counties that vaguely reflect tribal affiliations.

Although the world's youngest sovereign state South Sudan contains a

collection of communities that have contested their communal boundaries

for generations.

1.5 - Actors

As can be seen in OCHA's map South Sudan is comprised of a patchwork of tribal groups. In Jonglei three ethnic communities occupy largely homogenous parts of the state, as can be seen in the map of communal boundaries. The Lou Nuer are primarily from Akobo, Nyirol, and Wuror Counties - a band stretching across north-central and eastern Jonglei, marked in green. The Dinka inhabit the south-western portion of the state: Duk, Twic East and Bor Counties, marked in red. The Murle - a minority community in South Sudan- occupy Pibor County, marked in yellow. Whilst to the north of Jonglei are the Jikany Nuer in Upper Nile state, marked in blue. As borders are not always clearly defined nor mutually agreed upon, and pastoralist populations shift with the seasons, the map is only a general representation of community geography based upon information from the International Crisis Group and OCHA (ICG 2009).

Given the long history of attacks and counter-attacks between Jonglei tribes, pinpointing how and where a particular conflict cycle began is difficult. However, the Lou Nuer are involved in each of the primary conflict cycles. Access to water sources is essential for communities in the region, and the Lou Nuer are at a geographical disadvantage. During the dry season, they must travel with their cattle from their arid homeland to neighboring toiche areas in search of water and grazing areas. Iif they go west, they enter either Dinka or Gawaar Nuer territory. If they go northeast to the Sobat River, just across the border in Upper Nile state, they enter the territory of another Nuer sub-clan, the Jikany. Lastly, if they travel south to Pibor, they enter the territory of the Murle. In short, Lou must migrate either to Dinka, Gawaar, Jikany or Murle territories to sustain their cattle, providing a primary trigger for violent conflict (ICG 2009).

2.1 - Types of Environmental Problem

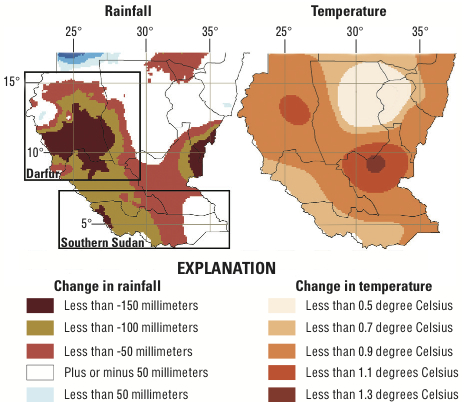

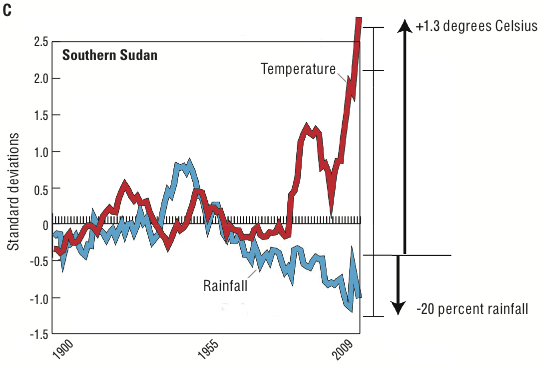

South

Sudan is becoming drier and hotter, which is consistent with

an increase in atmospheric circulation bringing

dry subsiding air during the rainy season. From 1975 to 2009

it is estimated that warming was more than 1.3C for

South Sudan. Given that the standard

deviation of annual air temperatures

in these regions is approximately 0.5C

these increases represent a very

large (2+ standard deviations) change from

the climatic norm (USAID, 2011). Such warming, in regions

with very high average air temperatures,

can amplify the impact of water shortages on agricultural

production and the carrying capacity of pasture.

South

Sudan is becoming drier and hotter, which is consistent with

an increase in atmospheric circulation bringing

dry subsiding air during the rainy season. From 1975 to 2009

it is estimated that warming was more than 1.3C for

South Sudan. Given that the standard

deviation of annual air temperatures

in these regions is approximately 0.5C

these increases represent a very

large (2+ standard deviations) change from

the climatic norm (USAID, 2011). Such warming, in regions

with very high average air temperatures,

can amplify the impact of water shortages on agricultural

production and the carrying capacity of pasture.

Climate change in South Sudan has been characterized by rising temperatures and decreased precipitation. Over the past 30 years South Sudan have been among the most rapidly warming locations on the globe, with station temperatures increasing as much as 0.4C per decade. At the same time rain fall in South from 1990 - 2009 rainfall has been, on average, about 20 percent lower than rainfall between 1900 and 1989 (USAID, 2011).

Paradoxically, although in line with predictions of climate change for the region, on the occasions when rain does occur it is in the form of intense but short-lived inundations (USAID 2011). In 2007, some 52, 219 households (267, 506 people) were affected by flooding in South Sudan. Jonglei and Upper Nile were particularly heavily hit, with Jonglei state cut off for several weeks (FAO 2010). Extreme flooding can wash away the topsoil required for vegetation growth, destroy existing crops, and provide a breeding ground for water borne diseases.

2.2 - Type of Habitat

The most remarkable topographic feature of Jonglei state is its flatness, for over 400km running north to south the average gradient is less than 10cm per kilometer (Howell & Michael, 1988). However, the ground is very uneven and generally the soil is rich in clay but poor in nutrients. Differences in height by just a few centimeters determine whether or not an area will receive spill over from a river or accumulated from rainfall. These slight topographic differences combined with the soil's composition have resulted in three definable forms of habitat (Howell & Michael, 1988), which in turn provide a key driver for the conflict. First, the Bahr el Jebel (White Nile) feeds a vast permanent swamp known as the Sudd. Second, surrounding the Bahr el Jebel and the Sudd are pasture known as "toiche". Toiche are a vital component of the grazing cycle for cattle during the dry season, without irrigated land or alternative water sources the toiche provides a vital resource for those dependent on the grazing economy. Third, beyond the Sudd and toiche are seasonal grasslands, which become inundated during the rainy season and arid during the dry season. During the dry season pastoral communities migrate with their cattle to areas with toiche and year-round water sources near to the Sudd and it's tributaries.

2.3 - Act and Harm Sites

The

current environmental phenomena of reduced rainfall and increased

temperature is reducing the carrying capacity of pasture in dry areas.

Under normal growing conditions, with plenty of

available water, energy from the sun causes evaporation

of water from the soil and transpiration of water vapor from

leaves. The combination of these two flows of water vapor is called

evapotranspiration. Year to year variations in evapotranspiration

are strongly related to changes in plant growth, cereal formation

and filling, end-of-season yields, and pasture biomass.

Increasing air temperatures, especially in

very warm regions, can reduce evapotranspiration.

As already high temperatures

rise, the environment becomes less hospitable to the

growth of flora. These warming effects can combine with

decreases in rainfall to further reduce

evapotranspiration and crop yield (USAID, 2011).

The

current environmental phenomena of reduced rainfall and increased

temperature is reducing the carrying capacity of pasture in dry areas.

Under normal growing conditions, with plenty of

available water, energy from the sun causes evaporation

of water from the soil and transpiration of water vapor from

leaves. The combination of these two flows of water vapor is called

evapotranspiration. Year to year variations in evapotranspiration

are strongly related to changes in plant growth, cereal formation

and filling, end-of-season yields, and pasture biomass.

Increasing air temperatures, especially in

very warm regions, can reduce evapotranspiration.

As already high temperatures

rise, the environment becomes less hospitable to the

growth of flora. These warming effects can combine with

decreases in rainfall to further reduce

evapotranspiration and crop yield (USAID, 2011).

South Sudan is experiencing substantially warmer and drier weather, and the combination of these effects is reducing evapotranspiration and producing more frequent droughts (USAID, 2011). In Jonglei prolonged drought and increased duration of the dry seasons directly impacts food security due to crop failure, and decreases availability of pasture in the flood plains. As a result cattle herders are forced to migrate to areas with more abundant resources, such as toiche surrounding the Sudd, bringing them into conflict with existing communities.

3.1 - Type of Conflict

Violence in Jonglei is reflective of conflict systems duplicated across the Horn of Africa. Pastoral communities in Sudan, Uganda and Kenya straddle, and often choose to ignore the existence of, national boarders (SAS, 2007b). Although this cannot be described as 'international' in the sense of a conflict between nation states, cross-border raids are common and can involve several hundred fighters at a time, in some cases over a thousand are involved. Because cattle raids rarely involves state forces directly, and are carried out far from the centers of power, they tend to arouse little public or international curiosity. However, the human costs of cattle raiding are far-reaching and present a growing array of risk to the security of the states involved (SAS, 2007b).

3.2 - Level of Conflict

3.2 - Level of Conflict

During the dry season pastoral communities living in the arid flood planes of Jonglei must travel to areas with more abundant sources of pasture. Dry season migration brings communities with a long-standing history of animosity into closer proximity, increasing the potential for conflict over access to resources or in the form of cattle raiding (UNEP, 2009). Current projections of climate change suggest that the region will become more arid, experience longer dry seasons, and more prone to drought, exacerbating the factors that drive conflicts over access to resources.

3.3 - Fatality Level of Dispute

According to United Nations Mission

in Sudan, over 2,500 people lost their lives in 2009 alone - a greater

death toll than the number of people who died in Darfur during the same

year (OCHA, 2009). Close to 5,000 lives have been lost in the region

since the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) between

the North and Southern Sudan in 2005. Between June and August 2011 approximately 1,000 people

were killed by members of the Lou Nuer and the Murle communities in

two reciprocal raids on each other. The escalating lethality of the

conflict meets the Correlates of War criterion of 1,000 deaths per

annum for a conflict to be defined as a civil war. However, as the

violence remains between communities and is not aimed at the state's

monopoly of power the term 'civil war' is an ill-fitting description.

Due to the indiscriminate and sectarian nature of the violence that

targets all aspects of life this violence would be best described as

ethnic cleansing, perhaps even genocide.

Click here to download an interactive Google Earth .kmz fil detailing the location of raids and recorded fatalities.

4 - ENVIRONMENT AND CONFLICT OVERLAP

4.1 - Environment-conflict Link and Dynamics

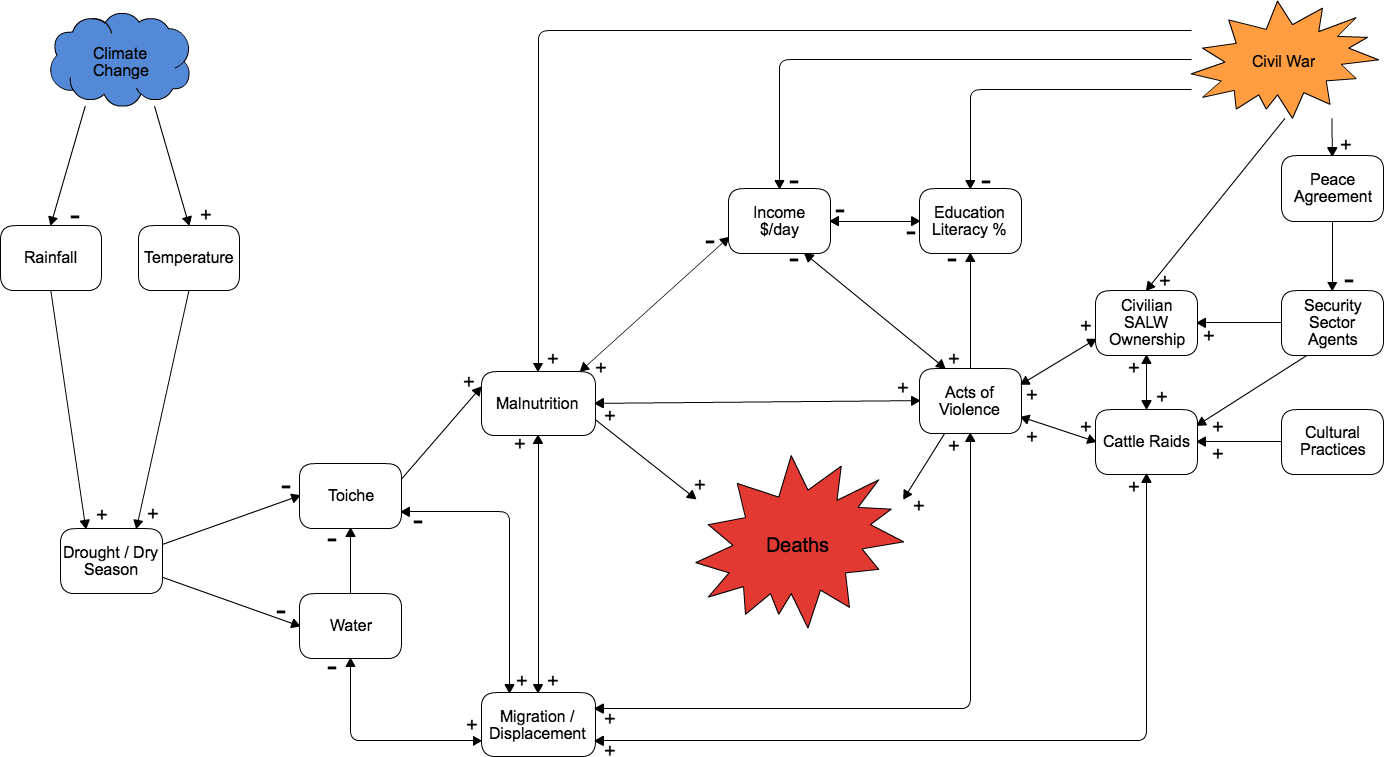

Causal loop diagram of the relationship between climate change and violent conflict in Jonglei, South Sudan |

As can be seen in the causal loop diagram, the environment-conflict relationship in Jonglei is a complex causational system of causational factors (highlighted below in bold). Three key dynamics related to climatic change, social and economic development, and the security situation in Jonglei state of South Sudan that collectively are contributing to armed conflict.

First, climate change is reducing average rainfall and increasing average temperature is South Sudan. The combination of these two factors is causing a decrease in evapotranspiration, resulting in reduced biomass of toiche and water resources. Subsequently, Jonglei state is becoming an increasingly arid environment characterized by intensified and prolonged periods of drought. Such changes are having a significant impact on an already fragile pattern of seasonal food production and migratory behavior. Food security is on the rise, demonstrated in the high-levels of malnutrition recorded by the FAO, which in turn is increasing mortality rates. As a form of adaptation to these environmental pastoral communities are migrating to areas with more abundant toiche and water. This combination of change and adaptation has caused a feedback loop, where by increased migration results in an exponentially increasing number of actors competing for an exponentially decreasing number of resources. As will be examined in the next section, contestation over increasingly limited resources is a key factor contributing to armed conflict in Jonglei State.

Second, civil war dominated the lives of those living in South Sudan for over thirty years. In 2005 the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) brought the civil war between Sudan and what is now the Republic of South Sudan to an end. A key condition of the CPA was the transition of the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) from a guerrilla force to a standing army quartered in formal encampments. During the civil war the SPLA had provided a modicum of (militarized) security, the CPA removed these informal security sector agents without their replacement by civilian law enforcement. The resulting security vacuum can be seen as a direct but unintended consequence of the CPA. Without a committed security sector apparatus there has been little to prevent or reduce civilian SALW ownership, or agents of the state to prevent and respond to cattle raiding. Implementation of the CPA can be seen as having a causational effect on the absence of law and order, and the subsequent proliferation of SALW in Jonglei state.

There is a long-standing causational relationship between cultural practices and cattle raiding. Cattle are an indicator of social standing and wealth, often used for restorative justice and marriage practices. The act of cattle raiding in of it self demonstrates a male youth's transition from adolescent to maturity. Cattle raids are conducted to replace castle lost to disease and pestilence, peaking during periods of drought; and to increase a total herd size to meet the requirement of social transactions such as dowry payments. During the dry season pastoral communities migrate with their cattle to areas with greater toiche and water resources. These patterns of migration bring communities with long-standing relationships of animosity into closer proximity as they contest essential resources. Migration as a response to environmental changes is a key, contributing factor to the frequency of cattle raids.

However, over the past 5 years the intensity and frequency of the acts of violence associated with cattle raids has increased dramatically. In the aftermath of three decades of civil war Jonglei state is awash with weapons, civilian SALW ownership has caused the lethality of acts of violence to increase dramatically. In response to cattle raids by those with automatic weapons some communities have sort to arm themselves as a means of self-defence, and /or to aid their own retaliatory attacks. Without security sector agents to provide restitution through the rule of law a feed back loop of vengeance has emerged, growing to such a scale as to present a threat to the stability of the region.

Third, what little social and economic development that existed in South Sudan prior to the country's civil war was all but destroyed by the conflict. The war increased levels of malnutrition, decreased opportunities for income generation, and formal education became almost non-existent. In the absence of social and economic development the vast majority of Jonglei's inhabitants are dependent on livelihoods that meet only the most basic requirements of existence. Armed violence stemming from conflicts between pastoral communities continues to reduce social and economic development. Acts of violence reduce income through the deaths of the most productive members of a community, whilst the subsequent climates of insecurity inhibit even micro-investment. Acts of violence reduce opportunities for education due to the destruction of infrastructure, whilst the subsequent climates of insecurity reduce the willingness of parents to allow their children to travel away from the community.

4.2 - Level of Strategic Interest

At the regional level conflict in Jonglei poses two challenges. First, as Collier (Collier, 2003) points out, under governed boarder regions such as Jonglei become a breading ground for armed non-state actors and organized crime, as demonstrated by the recent arrest of criminal groups involved in money counterfeiting in South Sudan. In other areas of the country cross-boarder cattle raiding between Uganda, Kenya and South Sudan has become an organized criminal activity that feeds into illicit meat markets (PP, 2009).

Second, in 1978 Sudan began a project to build a canal that would divert the White Nile away around the Sudd and re-enter the river down-stream. The rational behind this project was to prevent evaporation of the water in the Sudd, and provide greater water security for the down stream populations in North Sudan and Egypt (Ahmad, 2008). With two-thirds of the canal completed the project was abandoned in 1984 after the outbreak of the second Sudanese Civil War. Construction of the canal, and its potential to drain the Sudd have been cited as a key cause of the conflict - the issue was the focus of SPLA leader John Garang's Ph.D. thesis (Garang, 1981). In 2008 a new agreement was reached between the governments of South Sudan and Egypt - this has subsequently been re-affirmed by the Egyptian transitional government - that seeks to complete the canal by 2032 (Keys, 2011). Whilst continued insecurity in Jonglei will prevent completion of the project, completion of the project could significantly exacerbate the environmental conditions that drive resource conflicts between pastoral communities.

At the international level the Republic of South Sudan is a test case for international conflict resolution and post-conflict assistance. International donors have invested relatively large sums of money to rebuild South Sudan, for example the US aid in 2010 totaled $152,697,769 (USAID, 2011b). The increasing level of conflict in Jonglei in the period after the signing of the CPA has become a major focus of concern for the international community, anxious to carry out development programs unhindered by violence (ISS 2010).

4.3 - Outcome of Dispute

Cattle raids continue to be a leading source of violent conflict in Jonglei state, as stated earlier in the August 2011 attacks between Murle and Nuer militia that left over a thousand dead and tens of thousand displaced. This attack drew condemnation from the highest levels, head of UNMISS and the Secretary-General's Special Representative for South Sudan, Hilde Johnson, demanded, "This cycle of violence must stop! That so many people have been killed and injured again in such wanton destruction is unacceptable." Consequently one hundred and fifty UN peacekeepers have been dispatched to Jonglei to assist the security forces of South Sudan in their attempts to promote law and order (United Nations, 2011b). However, unless attempts at civilian disarmament are seen as equitable and a serious commitment is made to provide adequate security alternatives a, cycles of pastoral violence will continue and development will be stymied (Saferworld, 2010).

5.1 - Bibliography

Ahmad, A. M. (2008). Post-Jonglei planning in southern Sudan: combining environment with development. (IIED, Ed.) Environment and Urbanization , 20 (2), 575 - 586.

Brown, O., Hammill, A., & McLeman, R. (2007). Climate change as the 'new' security threat: implications for Africa. International Affairs , 83 (6), 1141-1151.

Collier, P. (2003). Breaking the Conflict Trap. (P. Colier, Ed.) Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

Evoy, C. M., & LeBrun, E. (2010). Uncertain Future: Armed Violence in Southern Sudan. Geneva, Switzerland: Small Arms Survey.

FAO. (2010). Plan of Action for South Sudan. United Nations, Food and Agriculture Organisation. Rome: United Nations.

Garang, J. (1981). Aspects for Development in Southern Sudan. Ph.D. Thesis, Iowa State University , Deparment of Economics.

GoSS. (2011). Retrieved 2011 7-October from Government of South Sudan: http://www.goss.org/

Howell, P., & Michael, L. (1988). Jonglei Canal: Imapact and Opportunity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

ICG. (2009). Jonglei's Tribal Conflicts: Countering Insecurity in South Sudan. International Crisis Group, Africa Section. London: ICG.

IIED. (2009). Adaptation to Climate Change: A vulnerability assesment of Sudan. International Institute for Economic Development, London.

Keys, P. (2011 30-March). Egypt €™s Jonglei Canal Gambit. Retrieved 2011 7-October from Water Security: http://watersecurity.wordpress.com/2011/03/30/egypts-jonglei-canal-gambit/

Leff, J. (2009). Pastoralists at War. International Journal of Conflict and Violence , 3 (2), 188-203.

OCHA. (2009). Humanitarian Action in Southern Sudan. United Nations, Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance. United Nations.

PP. (2009). Addressing Armed Violence in East Africa: A Report on World Vision Peacebuilding, Development and Humanitarian Assistance Programmes. Project Ploughshares.

Pratt, D., Gall, F. L., & Haan, C. d. (1997). Investing in Patoralism Sustainable Natural Resource Use in Arid Africa and the Middle East. World Bank. Washington D.C.: World Bank.

Saferworld. (2010). Consultations on community-level policing structures in Jonglei and Upper Nile States, Southern Sudan. London: Saferworld.

SAS. (2007a). Persistent Instability: Armed Violence and Insecurity in South Sudan. In S. A. Survey, Small Arms Survey 2007. Geneva: Cambridge University Press.

SAS. (2007b). Response to Pastoral Wars. Geneva: Small Arms Survey.

UN. (2011 23-August). Ban calls on South Sudan to restore security after deadly ethnic fighting. (United Nations). Retrieved 2011 7-October from United Nations News Center: http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=39364&Cr=south+sudan&Cr1

UN. (2011b 16-September). South Sudan: UN team investigates after fresh round of deadly cattle rustling raids (United Nations). Retrieved 2011 7-October from UN News Center: http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=39579&Cr=south+sudan&Cr1/

UNEP. (2009). Conflict and the Environment: Sudan. Post-Conflict Environmental Assessment, United Nations, United Nations Environment Program, Geneva.

UNICEF. (2008). Climate Change and Children: A human security challenge. Innocenti Research Center, UNICEF. UNITED NATIONS.

USAID. (2011). A Climate Trend Analysis of Sudan. Famine Early Warning Systems Network. USAID.

USAID. (2011b). South Sudan, Complex Emergency. USAID.

5.3 - Maps

Republic of South Sudan. Source: CIA World Fact Book

Pastoral Communities in Africa. Source: United Nations Development Program

Jonglei State, South Sudan. Source: Wikimedia

Communal boundaries in South Sudan. Source: OCHA

Boundaries between the Dinka, Jikany Nuer, Lou Nuer, and Murle communities of Jonglei State. Original Map Source: Google Earth

Temperature and rainfall change inSouth Sudan, 1980 - 2009. Source: USAID

Temperature and rainfall change in South Sudan, 1980 - 2009. Source: USAID

5.2 - Related ICE Case Studies

Case # 1 - NILE: Nile and Conflict by Michele Ameri

Case # 2 - SUDAN: Civil War in the Sudan: Resources or Religion? by D. Michelle Domke

Case # 203 - NILE-2020: Future Demands on Nile River Water and Egyptian National Security by Hans Catchcart

Case # 237 - UGANDA-CLIMATE: Uganda: Water Scarcity in the Ankole Cattle Corridor by Nicholas Steece

Case # 238 - TURKANA-MERILLE: Climate Change and the Turkana and Merille Conflict by Jesse Creedy Powers