- ICE Case 274: Tana River Disputes in a Drying Climate -

Aileen Andres

I. Case Background

1. Abstract

Clashes between the Pokomo and Orma Tribes of Tana River District in eastern Kenya reached a climax in August of 2012. This project explores the connection between the changing climate in Tana River and the violence between these two tribes. Historical roots are explored initially dating back to the 17th century migration that brought the Orma and Pokomo to the same region. Next the onset of micro-migration as a result of drought is introduced along with the affect of land grabbing by the Kenyan government and large corporations. The paper looks at the environmental aspects as well as the isolated conflict aspects before exploring the convergence of the twain. The second page titled 'Resources' provides a list of resources for organizations working in the Tana River District area, as well as policy suggestions as the groups move forward.

2. Description

Introduction

On August 22nd, 2012 while I was in Nairobi, I woke up to newspaper headlines reading ‘Massacre at Dawn’. A reported 48 people had been killed (Nation Team, 2012) as a series of deadly clashes between two tribes in the Tana River District was reaching a disastrous climax.

The clashes in this region are between two separate tribes, with two very different ways of life, living in one resource-scarce territory. The Orma and Pokomo tribes in Eastern Kenya are pastoralists and farmers respectively. The region is dry and prone to drought, with some sporadic rainfall during the rainy seasons (March-May, October-December). This difficult climate has been a huge factor in clashes between the farmers and pastoralists over water access and grazing rights (Nation Team, 2012).

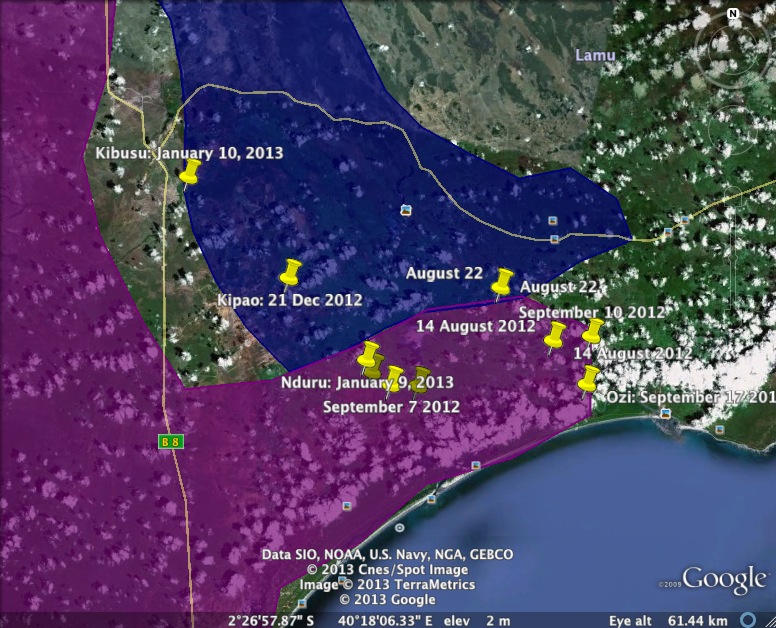

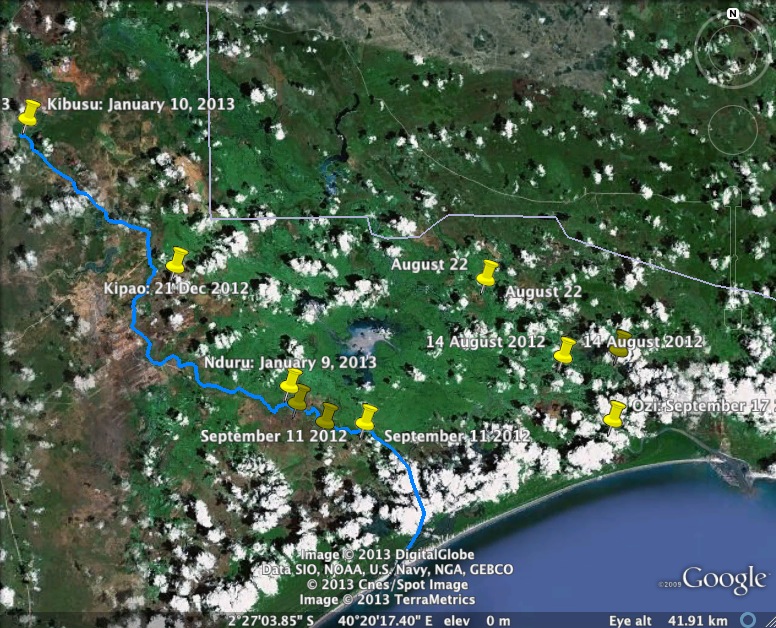

The clash in August was not the first instance of tension between these two groups, but it was the one with the most casualties, and sparked a series of revenge raids. Coupled with multiple smaller-scale attacks, there have been four major incidents: August 22nd with 48 casualties, a series of September incidents totaling 56 deaths and hundreds of huts burned, December 21st with 39 casualties, and finally most recently on January 9th 2013 11 people were killed (Daniel, 2013). In a matter of five months, nearly 200 people have been killed, hundreds of livestock have been stolen or slaughtered, and hundreds more huts have been burned (Daniel, 2013).

Historical Roots of Conflict

The Tana River District is one of seven districts that make up Coast Province, which lies along the Indian Ocean in the southeast part of Kenya. The district has about 180,000 residents, the majority of whom are Pokomo, Orma, and Wardey (Orma and Wardey are both pastoralists) (Practical Action, 2004). Both the pastoralists and farmers in the area derive their livelihoods from the River Tana, which is the largest river in the country. Despite this, the region as a whole is generally dry and experiences a drought at least once a year. The area around the river where farmers tend to live is wetter than the hinterland (especially during the dry season) where the Orma reside, but on the whole, the entire region’s rain accumulation varies and is extremely unreliable, and the region remains dry for the majority of the year (Practical Action, 2040).

With the difficult climate, the conflict has mainly centered around water access and grazing rights for cattle. The frequency and volatility of these clashes has increased over the years, and as of 2011, have reached a deadly climax. As of yet the Kenyan government has done little to quell the clashes. There is little to no infrastructure in the area let alone to address the conflict.

The Role of Migration and Micro-migration

Conflict between these two tribes is nothing new. In fact, conflict with the Orma and Pokomo dates back to the 17th century (Mwajefa, 2012). When they migrated from Ethiopia and Somalia respectively, settling along the Tana River where conflict emerged over arguments of land use and water access. Previous attempts at settlement of these inter-tribal disputes have been for naught as differences in culture, perceptions, and lifestyles have made it extremely difficult for these two peoples to coexist peacefully.

The Orma are a semi-nomadic group, whose ancestors hail from the powerful “Galla Nation” of Ethiopia and Northern Kenya (Joshua Project, 2012). They move with their cattle depending on the time of year – during the dry season, they remain near the bank of the Tana River while the rainy season drives them into the hinterland when the river floods. Historically, the Orma tribe has been known to flex their muscles around other pastoralists, becoming the most militarily superior people in Eastern Kenya and Southern Somalia in the early 17th century. However, conflict with the Ormo (the larger group from which the Orma are derived) and Ogaadeen tribes in the north drove the Orma south toward their current homeland (Turton, 1975).

The Pokomo are predominantly agriculturalists and fishermen living along the Tana River. Like the Orma, this group is not native to present-day Kenya either. In fact, they originated from Somalia and were driven down to their current home by wars with the Ormo in the north during the 17th century (Turton, 1975). An interesting a relevant philosophy the Pokomo have is called Sinidikia. This is a principle whereby all of the community members work together to achieve a common good. This same system reverberates into communal help in the event of individual problems. This strong culture presents the reasoning (Mwajefa, 2012) for ‘revenge raids’ as we have seen in recent violence with the Orma. Even in their initial settlement along the river, the Pokomo tribe divided themselves up into various clans, claiming the rights to access near the riverbank and on the flood plain (Guyo, 2009). Despite this, in the 1926 and 1938 Ordinance of Native Lands Trust, boundaries were formed, and the Pokomo were required to inhabit only nine reserves.

While there are a multitude of other elements in the clashes between the Pokomo and the Orma, the climate seems to be the most prevalent and most constant factor. The Pokomo claim rights to the land, while the Orma claim the waters, but after the 1980’s and 1990's and a string of irrigation schemes, the Orma moved into the hinterland while the Pokomo remained along the river (Practical Action, 2004). This has created an obstacle along the entirety of the river. As the area Pokomo reside in almost completely covers all riverbanks, the Orma are unable to access the river to water their livestock, which creates a situation in which co-habitation seems to be unattainable. During the dry season especially, pastoralists move their stock down towards the riverbanks to the water (Practical Action, 2004) (to which they claim unfettered access). However intrinsically, this infringes on the land that the Pokomo feel is unquestionably theirs. Movement on the part of the Orma towards the riverbank by necessity means that the herd goes through Pokomo farmland, which can be detrimental to any crops growing. In a fragile climate such as the Tana River Delta, land is precious and water is necessary. Reliance on these resources, and an inability to coexist peacefully is the fuel to this fire.

It’s this continuous cycle that has been in progress for generations. Now it seems that we’re at the point where the two sides are going to want revenge on each other no matter what happens. Even though the conflicts are predictable (it happens during the dry season), and would be preventable if effective conflict resolution mechanisms were utilized. However with the ever-changing climate worsening the situation and a now four century-long conflict, it seems that this hole is too big to cover up. Any lasting resolution to these conflicts is going to take a long process and creative problem solving.

During colonial times, this difference was settled with an agreement that farmers would allow herders pasture land and water corridors until the dry spells were over during which pastoralist would move back to their original areas (Mwajefa, 2012).

During Colonial times, a system was set up to allow herders water access until the dry season was over. However now with an increase in the dry season and the failure of this practice, conflicts are increasingly frequent and violent. The region is largely undeveloped due to lack of infrastructure or attention given to the arid regions of the country.

|

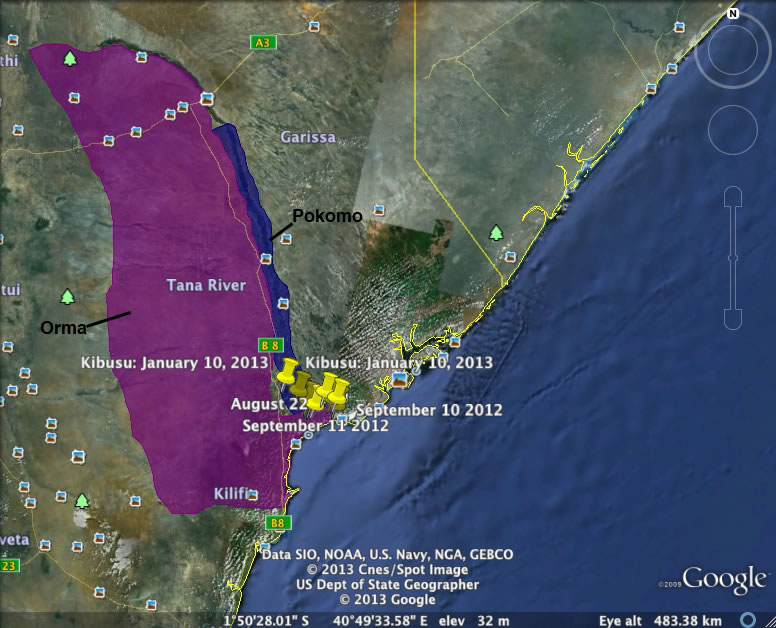

This image shows the divide between the Orma (in purple) and Pokomo (in blue) tribes in the Tana River District. Where the two tribes come together is more or less where the river flows, which you can see in the image below. The region that shows Orma is larger inherently because of their lifestyles as herders. The region is for the majority the hinterland through which they move throughout the year. The blue area, occupied largely by the Pokomo is along the riverbank. Moving east toward the river, the land begins to turn into the swampy area perfect for growing tropical crops and plants. The fact that there have not been many instances of violence in the area further inland is of particular interest. There is a cultural and religious divide between the Upper and Lower Pokomo. The Upper Pokomo, which make up 75% of the group are predominantly Muslim while the lower remaining 25% are predominantly Christian. It may be that the cultures between the Upper Pokomo and the predominantly Muslim Orma blend well together while the Orma and Lower Pokomo clash. |

| Image 1. Tribal borders in Tana River District |

|

|

| Image 2. Conflict Incidence between the Orma and Pokomo Tribes | Image 3. River flow near conflict areas |

From the maps above, we can surmise several different conclusions. One: clashes between the Orma and Pokomo occur between the Muslim Orma and the Christian population of the Lower Pokomo. No violence has been recorded between like-religion groups. Two: clashes occur where the two populations meet. This is the convergence zone when the Orma move in closer to the river in times of drought. Three: all incidents occur around the river or in the wetland area. These observations support the hypothesis that clashes occur only when the two groups are forced to be in close proximity of each other. The Orma herdsmen move into the area in order to feed their cows lest their entire herd dies. This movement causes conflict with the Pokomo for various cultural, religious, and ethnic reasons.

As of yet, little has been done on the part of the government to resolve these clashes. Local officials in the area are from either side of the conflict, so bias plays a large role in any conflict resolution attempted. The larger state government has indirectly contributed to the conflict in their management of land rights. Over the last few decades, the Kenyan government has handed away rights to land to larger corporations, forcing the Orma and Pokomo to relocate their villages.

Land Grabbing

Land grabbing by outside actors has also made this conflict all the more escalated, and the government has done very little to solve these issues. In 2007, Mumias Sugar Company, sugarcane companies, attempted to build a plant spanning 50,000 acres (20,000 hectares) (Wadhams, 2007) in the region. While sugarcane grows incredibly fast in wetland-type environments such as the delta would provide, opponents argued that its development could irreversibly ruin the region. At the same time, Mat International Sugar purchased 223,000 acres (90,000 hectares) of land adjacent to Mumias section of land (this land isn’t being created out of thin air either, it has been taken out of the hands of local residents) (Wadhams, 2007).

Flash-forward four more years, and entire villages have been evacuated. Gamba Manyatta Village, once almost 430 families strong was completely empty by the summer of 2011. A Canadian company, Bedford Biofuels picked up 25,000 acres (10,000 hectares) of land for a biofuel pilot project, and UK-based firm G4 received a license to get 69,000 acres (28,000 hectares). The local villagers were told to relocate to another area along the river. The catch? The “river” they were placed at is nothing more than runoff from these large plantations leaving drainage and pesticides for them to drink and use on their farms. The larger river was diverted to irrigate large companies leaving disease and garbage for the villagers (McVeigh, 2011).

At the very least, it seems that the current political climate in which every fourth Kenyan seems to be running for some sort of office, has resulted in lapses in security and enforcement. The January attack occurred “200 metres from a general service unit” (Daniel, 2013), however officials still failed to prevent it. Local leaders have also been pointed to for stirring up tensions between the communities (Mwakideu and Ponda, 2013) and inciting violence.

Lack of Infrastructure

Both the international and Kenya community alike have been pointing fingers at the Kenyan Government for their failure to mitigate the conflict in Tana River District. As mentioned above, there were a string of irrigation schemes in the 1980's and 1990's that have since dried up.

3. Duration

Begin Year: August 22nd 2013

End Year: Ongoing

Duration: Ongoing

4. Location

Continent: Africa

Region: East

Country: Kenya

5. Actors

Sovereign Actors

Government of Kenya

Non-sovereign Actors

Orma Tribe

Pokomo Tribe

United Nations/International Community

There are three main actors in this conflict, both sovereign and non-sovereign. The Government of Kenya is the sovereign actor, which has exhibited an almost active disregard for the situation and little to no ability in quelling the violence. There are subsets of the Kenyan Government involved including local MP’s (who are largely from either of the two warring parties), and police officers. However, the two main and active actors in this conflict are non-sovereign tribes: the Orma Tribe and the Pokomo Tribe. The Orma are largely Muslim pastoralists while the Pokomo are known to be Christian agriculturalists. Further removed from the conflict, but influential still is the international community, namely the United Nations. The UN has vocally condemned the violence (Mutambo, 2013) – urging there to be peace in the region. This reaction has been echoed by the larger international community, which has put pressure on the Kenyan Government to seek a resolution.

II. Environment Aspect

Tana River District is largely an undulating plain save for a few rolling hills placed haphazardly throughout. Like the rest of eastern Africa, Tana River District is predicted to experience a warming of .2°C to .5°C per decade (Deskanser, 2002). The mean annual temperature has increased from 1960-2006 by at least 1°C in Kenya according to Oxfam, and is experiencing a higher frequency of hotter days. In 1998, the district was affected by heavy and frequent el niño rains which damaged a lot of irrigation infrastructure, however aside from that, rain fall is erratic especially in the hinterland. The region experiences a high frequency of droughts, which now come at least once a year. Aside from being erratic, rainfall is bimodal and generally convectional. The mean annual rainfall ranges between 300mm and 500 mm.

The current trend in Kenya, especially in the eastern region is that rain is “increasingly unpredictable…falling less frequently…and in heavier bursts” (Oxfam, 2012). This means that eastern Kenya will experience more rain overall, but in less frequent, heavier, and unpredictable segments. While the past climate has allowed farmers and herders to plan accordingly to the historical ‘rainy’ and ‘dry’ seasons, current weather patterns are straying from that course.

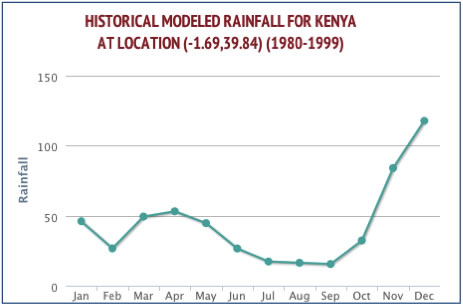

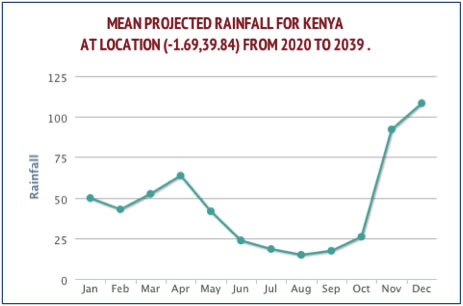

In terms of temperature, we can see an interesting pattern as demonstrated by the World Bank’s Climate department (The world Bank Group, 2013):

|

|

| Image 4. Historical Mean Rainfall in Kenya | Image 5. Predicted Mean Rainfall from 2020-2039 in Kenya |

The temperature isn’t necessarily going to get uniformly higher or uniformly lower according to this prediction. Alternatively, the low temperatures throughout the year will be lower and the high temperatures will be higher. This is an argument that weather patterns will become more extreme with climate change. The more extreme droughts will be harder on crop production, as will the increased likelihood of floods resulting from more polarized rainfall.

6. Type of Environmental Problem

Climate Change

7. Type of Habitat

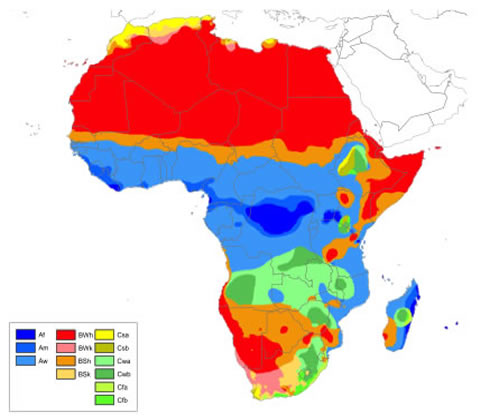

Tropical Savannah, or Tropical Wet and Dry climate (Peel et al. 2007).

This image shows the Africa section of the "Updated World Map from the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification". It shows the various bi-climatic habitats throughout the continent. As you can see, the southeast region of Kenya is classified as "Aw", or a Tropical Savannah. This type of climate is mostly concentrated along the equator as the map suggests. It is characterized by a monthly mean temperature above 18°C in each month of the year and a particularly long dry season.

Image 6. Habitats throughout Africa

8. Act and Harm Sites:

Conflict Harm Location: Tana River, Kenya

Conflict Act Location: Tana River, Kenya

III. Conflict Aspects

9. Type of Conflict

Civil

The reach of this conflict is mostly constricted to the specific region in which these two tribes live. There is no violence on the part of or against any party to another sovereign nation. Thus, the type of conflict is intrastate.

10. Level of Conflict

Resource Access

Infrastructure

Civil

This is a multi-faceted conflict without one specific root or trigger. It is perhaps most noticeably a resource access conflict as the conflict escalates when the two parties are both attempting to reach the same water source. Secondly, it is a conflict perpetuated by infrastructure, or lack there of. Were there proper mechanisms and infrastructure in place by the government, the hinterland might not be as susceptible to drier seasons as it is now. This would create no need for the Orma to travel into the land claimed by the Pokomo, and would largely ameliorate the situation. Neighboring Lamu and Kilifi counties experiencing similar tension albeit less violent, have cited landlessness as serious issues that need to be addressed, and which are only escalated by land grabbing by corporations. Lastly, this conflict is a civil one. The two warring tribes within Kenyan borders carry out the violence. Differing customs and lifestyles can be attributed to these groups lack of ability to coexist peacefully.

Additionally, it has been widely posited that the violence is largely politically motivated. The violence and run-up to elections coming at the same time seemed too much of a coincidence. The political motivation wasn't necessarily focused on the national Presidential election that was so high profile; but rather stemming from the local elective and gubernatorial election. The idea is that given the tense and close fight for local elective seats as a result of newfound power and leverage transferred by the new constitution, violence was encouraged as a way to displace voters. The governor elect, Hussein Dado, is from the Orma community as are the majority of newly elected officials (as well as Wardei, an ally of the Orma) (Ndunda, 2013). It would seem that given the demographics in the area, had the violence not occurred, these elections would have been much closer and perhaps the power dynamic would be vastly different today. In a post-election speech, Dado promised to address ethnic tension in the region saying, "his administration would prevent a return to tribal violence" (Standard Team, 2013).

11. Fatality Level of Dispute (military and civilian fatalities)

Low

The most recent string of conflict has resulted in death tolls numbering no less than 200 people, not counting the loss of livestock and personal property. The worst isolated incidents have resulted in a range of 30 to 60 deaths on the part of either side. These numbers do not include the 13,500 people displaced as a direct result of the violence, half of which are children, the other half being women and the elderly. An additional 30,000 people have been cited as being affected by the violence according to Kenya Red Cross (Kenya Red Cross, 2013). These victims have been pushed into IDP camps with insufficient resources, inability to provide shelter from the harsh elements, and high risk of disease.

Image courtesy of Katty HK

IV. Environment and Conflict Overlap

12. Environment-Conflict Link and Dynamics:

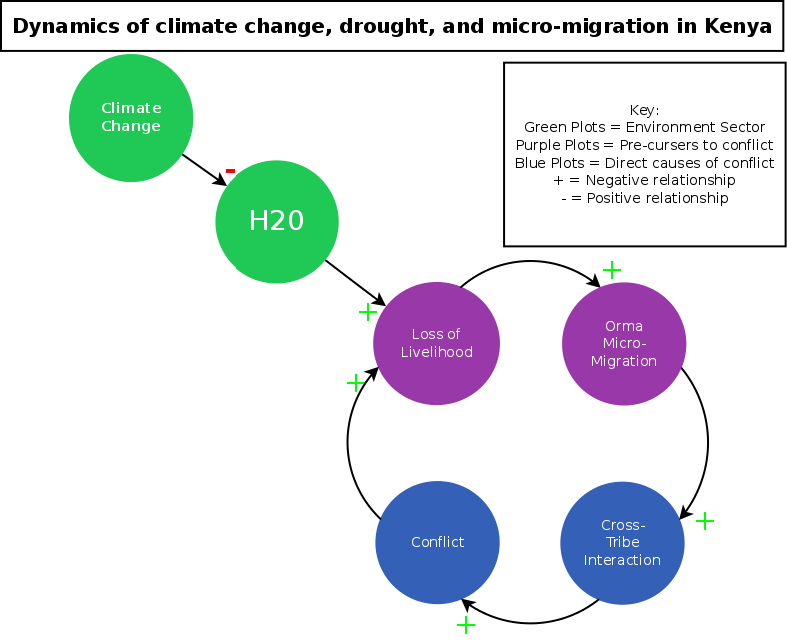

Like all other inter and intranational conflicts, there is no one cause or explanation for why so many lives have been taken by this violence. There is no magic fix, no easy change. The various elements in this case have all worked together creating the perfect storm for the situation as it is today. This being said, three main factors can be identified in the environment-conflict dynamics.

Micro-Migration

Instinctively, upon first glance of this conflict, one would probably assume that the conflict between the Pokomo and Orma arises from conflict over scarce water resources. However, upon further investigation into the actual level of water resources may lead to contradict this theory. In all actuality, the Tana River is doing pretty well. It’s more polluted than it was a decade ago, yes, but its volume has not actually suffered in the region being studied. Congruently, as previously stated, the change in climate expected to occur in Tana River District and Kenya as a whole will result in more overall rainfall, albeit less predictable and more erratic. This means that river flow will not necessarily suffer, although drought-esque periods will increase in length and cause what can be called a micro-migration.

As Ole Magnus Theisen found in his study, a drought can have a destructive effect on livestock herds, which will often lead to migration to water sources that “members from different ethnic communities have to share” (Theisen, 2012). In the case of the Tana River district, micro-migration has been observed in response to the different seasons throughout the year. When there is enough rain to keep the hinterland wet and to provide enough water for their livestock, the Orma keep away from the riverbanks, happy to be in the grass with their cattle. However, once a drought comes, the tribe is forced to migrate along riverbanks. However, it’s not necessarily that there is a shortage of water in the area that causes conflict. The two sides aren’t capturing as many drops and buckets as they can with each raid; rather, as Theisen finds with his study of cattle raids by the Pokot and Turkana, it is “not competition over scarce pasture or water…but the fact that the drought brought [them] into proximity of each other, thus facilitating raiding”.

We can also note from the precipitation graphs above, that the period of lowest rainfall is from July through September. This coincides with the timing of conflict. The violence between the Pokomo and Orma began and escalated in August, continuing on through September and again in January, another low point for precipitation. This stands to reason as the drier months cause interaction between the two groups.

A second antagonistic factor in this conflict is the action by actors external from the two primary groups: the state and corporations. Land grabbing, which was discussed earlier in this study has also contributed. Companies have acquired totaling hundreds of thousands of hectares in Tana River District. The land there is perfect for growing crops like sugarcane and other tropical plants. This has created a corral effect on the local population. Villages being relocated means groups that had once lived with a comfortable zone between them are now pushed closer and closer together.

13. Level of Strategic Interest

State

Sub-State

14. Outcome of Dispute

In Progress

V. Related Information and Sources

15. Related ICE Cases

Case #1: Nile River Dispute

Case #46: Ethnic Cleansing and the Environment in Kenya

Case #196: Darfur Drought and Civil War

Case #254: Pastoral Violence in Jonglei

Case #256: Rainfall and Migration: Somali-Kenyan Conflict

16. Relevant Websites and Literature

Blench, Roger, and Mallam Dendo. "The transformation of conflict between pastoralists and cultivators in Nigeria." Africa, September 2003.

Daniel, Nyassy. "11 killed in fresh fighting in Tana Delta as DO flees villager's attack." The Nation, January 10, 2013.

Deskanser, Paul V. Impact of climate change on Africa. WWF, Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 2002.

Guyo, Fatuma Boru. Historical Perspectives on the Role of Women in Peace-making and Conflict Resolution in Tana River District, Kenya, 1900 to Present. MA Thesis, Miami: Miami University, 2009.

Joshua Project. The Orma of Kenya Ethnic People Profile. 2012. http://www.joshuaproject.net/people-profile.php?peo3=14214 (accessed April 17, 2013).

Kenya Red Cross. Urgent KRCS appeal for Tana River residents. Kenya Red Cross, 2013.

Makoye, Kizito. "Drought drives Tanzanian herders into conflict with farmers." Thompson Reuters Foundation, June 12, 2012.

McVeigh, Tracy. "Biofuels land grab in Kenya's Tana Delta fuels talk of war." The Guardian, July 2, 2011.

Mutambo, Aggrey. "UN condemns 'inhumane' Tana violence." The Nation, January 10, 2013.

Mutinda, Munyao. "Power struggles and conflict over use of land fan Tana Delta clashes ." The Nation, August 25, 2012.

Mwajefa, Mwakera. "A history of war between herders and crop farmers." The Nation, August 23, 2012.

Mwakideu, Chrispin, and Eric Ponda. "Fresh violence in Kenya's Tana River Delta." DW, January 09, 2013.

Nation Team. "48 villagers killed in revenge attack." The Nation, August 22, 2012.

Ndunda, Ernest. "Orma, Wardei win posts over Pokomo in Tana River." Standard Digital, March 09, 2013.

Oxfam. Oxfam in Kenya. London: Oxfam International, 2012.

Peel, M.C., B.L. Finlayson, and T.A. McMahon. "Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification." Hydrology and Earth System Sciences Discussions 4, no. 2 (2007): 439-473.

Practical Action. "Tana River District: A showcase of conflict over natural resources." Practical Action, 2004.

Standard Team. "Pokomo, Orma united during Governor's oath." The Standard Digital, March 27, 2013.

The World Bank Group. Climate change knowledge portal 2.0. 2013. http://sdwebx.worldbank.org/climateportal/index.cfm?page=country_future_climate&ThisRegion=Africa&ThisCcode=KEN (accessed 2013).

Theisen, Ole Magnus. "Climate clashes? Weather variability, land pressure, and organized violence in Kenya, 1989-2004." Journal of peace research 49, no. 81 (2012): 80-96.

Turner, Matthew D. "Political ecology and the moral dimensions of “resource conflicts”: the case of farmer–herder conflicts in the Sahel." Political Geography 23, no. 7 (September 2004): 863-889.

Turton, E R. "Bantu, Galla and Somali Migrations in the Horn of Africa: A Reassessment of the Juba/Tana Area." The Journal of African History 16, no. 4 (1975): 519-537.

Wadhams, Nick. "Kenya Plans for Huge Sugar Factory Spark Bitter Dispute ." National Geographic, September 24, 2007.

Warah, Rasna. "There must be more to the killings in Tana Delta than meets the eye." The Nation, January 20, 2013.

[28 April 2013]