| ICE Case Studies

|

Tasmania and the European Invasion by Rehan Ali |

I.

Case Background |

![]()

|

||

|---|---|---|

Abstract |

Summary |

These words, written by H. G. Wells in the preface to The War of the Worlds, are a sobering reminder of the costs that colonialism extracted from native populations the world over. As he emphatically remarks, Tasmania's reputation as the place where an absolute genocide took place turns out to be more interesting and not as straight-forward as Orwell stated. Unfortunately for the Tasmanians, however, the war did not end with their victory over the 'foreign' British invaders. But while the conflict between settler and aboriginal was severe and the cost to natives high it was not absolute and modern times have seen the re-emergence of the question 'who is a native Tasmanian'. This study aims to detail the period in Tasmanian history when colonists first came to island and the impact of that period on Tasmanian life.

|

Description |

Pre-History |

Tasmania was initially populated some 35,000 years ago via the Bass Strait, a northern land-bridge that connected the island to continental Australia. It is unknown whether settlers first came to Tasmania in waves over a period of years or in a single migration, but by 8,000 BC they were effectively made the de facto residents when it became an island following the end of the last ice age and the flooding of the Bass Strait.

|

|

Aboriginal Cultural Life |

From that period on the Tasmanians (ethnonym: lutrawita) are generally considered to have been nomadic hunter-gatherers divided into nine tribes, each with their own language. Each tribe is said to have consisted of six to fifteen groups of thirty-five to seventy people. They were skilled in weaving and engaged in limited sea-travel, mainly in order to fish. At the start of the colonial encounter there were estimated to be 4,000 to 10,000 natives resident on the island, with 5,000 being the generally accepted figure. The pre-contact Tasmanians made full use of the food resources available to them on the island, which were varied enough to offer a well-rounded diet. It is thought that although fish were plentiful in the surrounding waters only shellfish was regularly eaten by the Tasmanians. They made and used boats to travel along the coastline although never apparently as far as continental Australia. The only known item of clothing was a kangaroo skin cloak with occasional, minimal ornamentation. There is little evidence left of tools that were used although we know of the spear and the waddy, a stick used in hunting. Of the stone instruments collected in the modern period there is little knowledge on what time period they are from or who used them. Physically, an interesting point of difference between the Tasmanians and the Australians was their hair. While continental aboriginals have wavy hair varying in color from black to blond, the Tasmanians had tightly coiled black hair, which may suggest a link to Melanesians. This cannot be substantiated, however, because of the absolute lack of Tasmanian DNA. The fact that very few records were kept regarding aboriginal life at the time of the first encounter means that there isn't much evidence to conclude anything about the Tasmanians.

|

|

First Contact 1642 |

Recorded history of Tasmania begins with the Dutch explorer Able Tasman (1603-1659) who sighted the island on the 24th of November, 1642, and named it Anthoonij van Diemslandt after the Governor of the Dutch East Indies, who was his patron. Although Tasmania was first sighted by the Dutch they never tried to maintain it as part of their empire, and the expansionist British soon arrived on the scene to take the island over. Captain James Cook of the British navy sighted the island more than a century later, in 1777, while mapping the coast of continental Australia. Soon after the sighting the British shortened its name to Van Diemens Land and claimed it in 1803 as a penal colony for criminal offenders from continental Australia.

|

Penal Colony 1803 |

The first settlement was at Risdon Cove in the south-east. A year later another settlement was established 3.1 miles (5 km) to the south, where freshwater was more plentiful. This second settlement was named Hobart Town or Hobarton after Lord Hobart, the Colonial Secretary at the time of establishment. Since both of these settlements had a penal purpose the early settlers were convicts, mostly repeat offenders, along with some men who served as their guards. As per the the laws of the time these criminals did not serve their time as prisoners but as supervised settlers. In addition to the above, other major settlements were at Port Arthur in the the south-east and at Macquarie Harbor on the west coast. The intention behind establishing these colonies was not only to create an isolated prison for criminals but also to use the prisoners to develop the land agriculturally and make it habitable for future migrants. While Tasmania had ample resources to support the native population there weren't any resource exports to continental Australia because Tasmania wasn't a fully integrated part of the British Empire and most of the traffic flow, such as trade and people, was to the island rather than from it.

|

|

First Phase of Conflict 1803 to 1808 |

Given that most of the settlers were prisoners and that there was an existing indigenous population conflicts were inevitable. Initial fights were over foodstuff such as the kangaroo and over land rights. While the aboriginals were spread all over the island the colonists were mainly based around Hobart and the south-east. As the number of prisoners increased they fanned out from the south-east into the rest of the country demarcating and claiming land as they pleased. The aboriginals had no concept of owned land since theirs was a nomadic society of hunter-gatherers and they often crossed into territory that the settlers had claimed and demarcated, leading to an escalation in conflict which eventually resulted in the Black War.

|

|

Second Phase of Conflict 1808 to 1823 |

Being a penal colony the number of white females on the island was limited, and so the settlers took to kidnapping aboriginal women as partners. In addition, children were also taken and kept as slaves, an act that one Governor Sorrell expressed his utmost disgust about and which he ordered summarily stopped. As a result, these slave children were taken by the authorities to Hobart Town, where they were allegedly sheltered and educated. The kidnapping of their women by the British also increased tensions between the aboriginal tribes, which led to infighting and started a general decline in the aboriginal population. Unlike in North American, disease from the colonists was not really a major decimating factor for the aboriginal population until 1829. By that time extended periods of interaction and transmission of diseases such as influenza, pneumonia, and dysentery via aboriginal women started to effect the remaining population. There are not really any records of aboriginal deaths due to disease so the actual impact is hard to estimate.

|

|

Aboriginal Resistance 1824 to 1828 |

An increase in the settler population and their expanding land use led to more intensive conflict. In addition, newer settlers refused to provide food rations to the aboriginals, something their predecessors had done as form of payment for the land. The result was that the number of raids on settler farms increased starting in 1824 leading to what some scholars call an 'aboriginal guerilla war'. In these operations aboriginals would raid settler farms for foodstuff, although whether these were concentrated and planned attacks on the part of the aboriginals in order to defend their homeland is a topic of some debate. The result was that by 1828 the colonial government declared martial law and the start of the 'Black War', which, as the name suggests, was a war on the Tasmanian blacks, as they were called at the time.

|

|

|

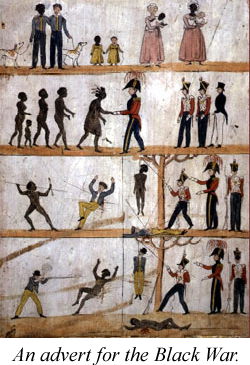

Black War & the Black Line 1828 to 1830 |

The year 1828 saw the start of the 'Black War', a period of unambiguous conflict between the two sides. This came to a head in the Black Line incident of 1830 when Lieutenant Governor George Arthur ordered every colonist to form an impenetrable human line and sweep across the island to trap the natives in the Tasman peninsula in the south-east. Although entirely unsuccessful it is said to have strained the aboriginal psyche to the point where the Tasmanians accepted a plan to be expatriated to Flinder's Island on the north-east coast. The end of the Black Line fiasco effectively ended the period of armed fighting between settlers and aboriginals and forced the colonial government to try pacification as an alternate measure: migration to nearby Flinder's Island.

|

|

1830 to 1847 |

This migration plan was proposed by one George Augustus Robinson, an amateur preacher who was appointed Chief Protector of the Aboriginals in 1830. After his appointment he embarked on an initial eight-month tour of Tasmania using the services of Truganinni, a full blood aboriginal, as his translator. His mission was to find and convince the remaining tribes to accept expatriation to Flinder's Island, off the north-west coast of Tasmania. The fact that he was accompanied by nine aboriginals no doubt aided in his efforts and by 1835 he had managed to convince some two-hundred natives to accept the government's plan of re-settlement in comfortable living conditions and eventual repatriation. Robinson's involvement, however, ended soon after the aboriginals were settled on Flinder's Island. Much to their dismay the island was more a prison that a haven and the poor conditions and lack of food and shelter led to the deaths of some three-fourths of the migrant aboriginals. Of the original two-hundred only some fifty survived to be repatriated to Tasmania in 1847.

|

Truganinni 1812 to 1876 |

One of the repatriated was Truganinni, an aboriginal born near Hobart around 1812. Born during the influx of white settlers, Truganinni saw much tragedy in her life as her mother was killed by whalers and her first fiancé was killed while saving her from being abducted by the settlers. In addition, her two sisters were kidnapped in 1828 and taken to southern Australia as slaves. She became Robinson's official translator during his attempts to convince the remaining aboriginals to willingly move to Flinder's Island in 1830. Five years later Truganinni and about two hundred other aboriginals, tired of being hunted like animals, agreed to go to Flinder's Island, at Robinson's request. As mentioned above, she was eventually repatriated in 1856 to Oyster Cove, near Hobart.She died there in 1876. Despite her wish to be cremated, her skeleton was put on display by the Royal Society of Tasmania. It was only a full century later in 1976, when Australia was coming to terms with her colonial past, that she was finally cremated and her ashes were scattered as per her wishes. |

|

|

Repatriation to the Modern Era |

By the time they returned to Tasmania proper the number of aboriginals was dismally low to the point where Truganinni was said to be the last pure-blood Tasmanian. This claim was maintained until the start of the twentieth century when Fanny Cochrane Smith, the last speaker of a Tasmanian language, and, as some say, the last full-blood, died. Fanny was actually born on Flinder's Island in 1834 after the aboriginal relocation. She went on to have eleven children and is said to be the ancestor of a large percentage of the population now claiming aboriginal status. The century following repatriation, meanwhile, saw the virtual disappearance of claimants to aboriginal ancestry in Tasmania, an observation that can be linked to the deliberate absorption on the part of the remaining natives into the general Australian populace, peopled by half-bloods, Pacific Islanders (especially the Maori), and south-east Asians. The modem era, however, with its emphasis on pre-European history and natives' rights has seen a resurgence in the number of claimants to native ancestry, some with official documentary proof. While this proves that the lutrawita were not exterminated by gun or disease it does little to assuage the fact that Truganinni was the last aboriginal to have experienced traditional Tasmanian life as it was lived in the years before the European arrival. Unfortunately, virtually nothing survives to tell us about this traditional life as the early settlers had no interest in amateur anthropology and all surviving aboriginals tried to hide themselves in mainstream society as much as possible. Because the Tasmanians had been separated from mainland Australians for a long period of time we are unable to extrapolate Tasmanian culture from mainland Austra1ian culture.

|

Modern Tasmania |

In 1853 all transportation of prisoners to Van Diemen's Land ceased. In order to give the island a new face and move away from its penal past it was renamed Tasmania in honor of Abel Tasman. Hobart Town became a city in 1842; the name was simplified to Hobart in 1875.

|

|

Summation |

It is thought that at the time of British settlement in 1803 the indigenous population was between 4,000 and 10,000 people. The total number of men sent as part of the penal program between 1803 and 1853 is estimated to be 75,000, or eight to nineteen times the number of aboriginals thought to exist at the time of first colonization. If not by force of arms and government decree it is clear that the settlers' sheer numbers would eventually overwhelm the native population.

|

|

Duration |

50 Years 1803 to 1853 |

The total period of the conflict was approximately 50 years, from 1803 to 1853.

|

Location |

Continent: Australia

Region: South-east

Country: Australia |

The location of the conflict was Tasmania, a group of islands off the south-eastern coast of continental Australia. Most of the conflict took place in Tasmania proper, with some later conflict taking place on Flinder's Island, in the northeast.

|

Actors |

Aboriginal Tasmanians and British Colonists |

There are basically two groups of actors in this conflict: aboriginal Tasmanians and British settlers. The European settlers acted in both an official and un-official capacity. During the initial stages of their settlement they often fought with native Tasmanians without official sanction. Later, during the Black War period, the government in Australia sanctioned the killing and forced re-location of aboriginals. The Tasmanians, meanwhile, except for the 1824 'aboriginal guerilla war' usually acted in an ad hoc manner, fighting over land, food, and women in a disorganized manner. |

| II

|

||

The environmental impact of the Tasmanian conflict was actually negligible. There are no records of any environmental degradation due to colonization except for the increased use of lumber and other resources in the 19th century, but nothing especially damaging. This can be attributed to a number of factors such as a general lack of immigration because of the absence of immigration initiatives, and no gold rush, as happened on continental Australia. Because of Tasmania's existence outside of the continent migration has usually been away from the island, a trend that started as soon as its colonial residents stopped being classified as prisoners in the mid-19th century and were free to move away. It can be said that the land that the aboriginals and settlers fought so bitterly over was arable land, and so could have supported growing populations, i.e. the aboriginals and the settlers. It is unlikely that the conflict was the result of a military initiative to control both sides of the strait between continental Australia and Tasmania but more likely was a clash between two cultures who didn't understand one another's ideas about property. The aboriginals had no concept of privately-owned land and the settlers had no concept of shared land. Unfortunately for the aboriginals the settlers were greater in number and had much better firepower. As far as can be ascertained, the Tasmanian aboriginals and the native animal species lived in relative harmony. There are no records of the extinction of any species well into the twentieth century. The 'Tasmanian Tiger' (thylocinus cynocephalus) did not die out until the 1930's, when the last captive thylacine died out. There have been sightings of thylacine in the wilds of Tasmania, although none of these sightings have been confirmed by scientific sources. It is worth noting that today Tasmania promotes itself as the "Natural State" because of its unspoiled environment. As part of this program the government has demarcated some 40% of its land as national parks, reserves, and World Heritage Sites.

|

||

| Type of Environmental Problem | Land Rights |

The only ones to lose land were the Tasmanian aboriginals, who lost all land rights after they migrated to Flinder's Island. Because of the assumption that all aboriginals had died out by the late 19th century there were also no land claims lodged against the government as happened on continental Australia. By sending Tasmanian survivors to Flinder's Island the colonists effectively created the terra nullius that they had failed to find in Australia when they first arrived.

|

| Type of Habitat | Temperate |

Much of Tasmania is mountainous, with about half of the island 1000 feet above sea level. There is a small plain, which is the area colored light and dark brown in the center-north on the map above. The western half of the island consists of rainforest (the dark green portion of the map), while the eastern half has a mixture of forests and plains. The plant life on the island is similar to that of continental Australia and southern Oceania. The animal life consists of Australian-type marsupials. Despite their names, the Tasmanian Tiger (thylacinus cynocephalus) and the Tasmanian Devil (sarcophilus harrisii) were not unique to Tasmania but only survived there because the dingo didn't exist on the island. On the mainland both went extinct many centuries ago because of the predatory dingo which is larger animal. The last known thylacine died in captivity in 1936. The Tasmanian coat of arms (at the top of the page) has two thylacines on it.

|

| Act & Harm Sites | England via continental Australia and Tasmania |

The act and harm sites were the same and the act and harm were immediate since all the actions involved physical harm, the results of which were felt in a relatively quick timeframe. It can be summarized by saying that Britain enacted a genocide (intentional or un-intentional) on the aboriginals of Tasmania via its government, prisoners, and settlers from Australia. The word 'Australia', however, needs to be explained: it does not refer to the modem country of Australia which was formally created years after the Black War (1828), nor to the government of Australia or Tasmania, both of which had differing policies towards the aboriginals that vacillated between open hostility and forced pacifism. Rather, it should be thought of as referring to the colonists that arrived on that grand continent in 1803.

|

| III | ||

The conflict between British settlers and the Tasmanian natives was a pre-nation conflict. This means that it took place before Australia was an official country, and when Tasmania was considered a separate entity from continental Australia. From a modern perspective it could be considered either a civil war or a simple conflict due to expansionism in an un-incorporated land. Since this was a conflict that took place before any official records were kept casualty rates are extremely hard to come by. This is further complicated by the fact that there are no definite numbers on how many Tasmanians lived on the island before the Europeans arrived. Modem historians vary their estimates from 2,000 to 10,000 people killed, with 5,000 being the figure generally accepted. Although the body count is in-determinate the destruction of the Tasmanian languages and culture was absolute.

|

||

| Type of Conflict | War |

This was a civil, pre-state war. In many ways it was a founding conflict of Australian history because it placed the island of Tasmania squarely within continental jurisdiction. It should be remembered that Tasmania hadn't been a part of mainland life for some 10,000 years, since the last ice age. European settlers effectively brought it back into the mainstream of Australian life.

|

| Level of Conflict | Medium |

As mentioned, this was an intra-state war where the casualty numbers were between 4,000 and 10,000. As such, it would seem to be of medium impact in terms relative to rest of the case-studies but in absolute terms its impact should be considered to be extremely high because of the devastation of traditional culture. The process of conflict was rather piecemeal in execution, with whites shooting and killing aboriginals in various encounters rather than in a full-scale battle. The only attempt to make a concentrated attack on the aboriginals, the Black Line,

|

| Fatality Level of Dispute | 5,000 (estimation) |

Although the conflict had the implicit agreement of mainland government officials at various stages it cannot be said that there were any military fatalities since military forces were not explicitly used. Instead, settlers were fighting natives. Aboriginal fatalities numbered in the thousands and it is likely that a few hundred settlers may have died. This is based on the only real numbers that we have, which are from official Tasmanian records from 1825 to 1830, co-incidentally the last year that we are concerned with. Records such as those of the Australian Bureau of Statistics show that in this period there were 27 settler deaths at the hands of aboriginals, including quite a few by spear. Expanding these numbers to the previous 17 years (to 1803 when settlers first came to Tasmania) gives a calculated total of 153 deaths. The sum for the period 1803 to 1830 then approaches a total of 180 settler deaths versus some thousands of aboriginal deaths. Whether this figure is realistic is difficult to gauge because of the dearth of records, but it is certainly at least possible. Summation: Military fatalities: none; no military forces were actually used. Total: between 4(3) and 1(5) on logarithmic levels.

|

| IV | ||

| Environment-Conflict Link & Dynamics | Direct - Resource |

This was a resource conflict over land, resources, and women (in order of importance). Since it was a resource conflict it was short-term and lasted for approximately 50 years. |

The system dyamics at play in Tasmania were quite straightforward. The British aggressors were motivated by a desire for Tasmanian land to increase the size of their empire and sent convicts from Australia to occupy and prepare it for later settlement. This exporting of Australians resulted in the occupation of aboriginal land and free use of its resources resulting in the destruction of the aboriginal race within 50-or-so years.

|

||

| Level of Strategic Interest | Sub-state |

Although this was a sub-state conflict it was focused on the main island of Tasmania for most of its duration except for a short period on Flinder's Island when there was a brief lull in conflict because the two parties were physically separated.

|

| Outcome of Dispute | Victory |

Victory for the European settlers. The loss to the aboriginals was almost absolute, their physical survival being the only positive outcome for them. Their victory gave the British the entire island of Tasmania, and allowed them to incorporate it into Australia proper.

|

| V | ||

| Related ICE Cases | By type |

Genocide Cases 1. Rwanda and Conflict - Details the 1994 genocide involving Hutus and Tutsis. 2. Ethnic Cleansing and the Environment in Kenya - Details the 1993 genocide between the Maasai and Gikuyu. 3. Marsh Arabs and Iraq - Talks about the forced relocation and repression of the Saddam years. 4. Neanderthal Extinction and Climate Change - Deals with the theory of how homo-sapiens and neanderthal interacted before the disappearance of the latter.

De-forestation Cases 5. Guatemala-Maya Civil War and Deforestation - Deals with the effects of the US-instigated civil war. 6. Ethnic Conflict and Deforestation in Kalimantan - Overview of the Muslim-Christian conflicts of 1996. 7. Amazon Deforestation and Brazil Land Problems - Looks at the effects of population migrations to the Amazon area in northern Brazil. 8. Armenian Independence and Deforestation - Talks about the creation of the modern state of Armenia.

Resource Cases 9. Aceh and Indonesia - Overview of the local resistance in Aceh against the Indonesian government's attempts to create an oil network in the region. 10. Mayans, Climate Change, and Conflict - Examines the causes of the decline of the Mayan empire. 11. Anglo-Boer: Britain's Vietnam - Looks at the war fought between the Boer and the British for the area of South Africa. 12. Ansazi Water and their Disappearance - Details the 1994 genocide involving Hutus and Tutsis.

|

Relevant Web Sites and Literature |

In alphabetical order |

Alexander, Alison (editor). The Companion to Tasmanian History. Hobart: University of Tasmania, 2005. Arthur, George. Van Diemen's Land: Copies of All Correspondence between Lieutenant-Governor Arthur and His Majesty's Secretary of State for the Colonies. On the Subject of the Military Operations Lately Carried Against the Aboriginal Inhabitants of Van Diemen 's Land. Hobart: Tasmanian Historical Research Association, 1971. Australian Bureau of Statistics. "1384.6 - Statistics - Tasmania, 2005." Tasmania - Statistics Blake, Philip. Secret Tasmania. Sydney: New Holland, 2002. Bonwick, James. The Daily Life of the Tasmanians. London: Sampson Low & Son & Marston, 1870. Bonwick, James. The Last of the Tasmanians; or, The Black War of Van Diemen's Land. Adelaide: Libraries Board of South Australia, 1969. Cato, Nancy, and Vivienne Rae-Ellis. Queen Trucanini. London: Heinemann, 1976. Chauncy, Nan. Hunted in Their Own Land. New York: Seabury Press, 1973. Davies, David. The Last of the Tasmanians. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1974. Haydon, Tom (director). The Last Tasmanian. Del Mar: CRM!McGraw-Hill Films, 1980-1984. McGrath, Ann (editor). Contested ground: Australian aborigines under the British Crown. St. Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 1995. Mollison, B.C. The Tasmanian Aborigines. Hobart: University of Tasmania, 1974. Morgan, Sharon. Land settlement in early Tasmania: creating an antipodean England. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992. Plomley, N. J. B. (editor). Weep in silence: a history of the Flinders Island aboriginal settlement, with the Flinders Island journal of George Augustus Robinson, 1835-1839. Hobart: Blubber Head Press, 1987. Plomley, N. J. B. The Tasmanian Aborigines: A Short Account of Them and Some Aspects of Their Life. Launceston: Plomley, 1977. Price, Pat Peatfield. The First Tasmanians. New York: Rigby, 1984. Reed, Bill. Truganinni. Richmond: Heinemann Educational Australia, 1977. Robson, Lloyd. A History of Tasmania, Volume 1: Van Diemen 's Land from the Earliest Times to 1855. Oxford University Press, 1983. Roth, Henry Ling. The Aborigines of Tasmania. 1899; rpt. Hobart: Fullers Bookshop, 1968. Ryan, Lyndall. The Aboriginal Tasmanians. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 1981. Shakespeare, Nicholas. In Tasmania. London: Harvill Press, 2004. Travers, Robert. The Tasmanians: The Story of a Doomed Race. Melbourne: Cassel!, 1968. Turnbull, Clive. "Tasmania: The Ultimate Solution." Racism: The Australian Experience. A Study of Race Prejudice in Australia. Vol. 2, Black Versus White. Edited by Frank S. Stevens. New York: Taplinger, 1972: 228-34. Turnbull, Clive. Black War: The Extermination of the Tasmanian Aborigines. Melbourne: Lansdowne Press, 1965. Winschuttle, Colin. The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Vol. 1: Van Diemen 's Land. Paddington: Macleay Press, 2002.

|