-->Transnistria-Moldova Territorial Dispute (ICE)

1. Abstract

Transnistria-Moldova Conflict: Territorial Dispute

|

Transnistria is referred to in one of three

principal

ways:

Stinga Nistrului (Left Bank of the Nistru) (by official

Moldovan sources)

Pridnestrovskaja Moldavskaja Respublika ((PMR) (by

Transnistrian official sources)

Moldovan Republic of Transnistria (MRT) (by European Court

of

Human Rights) |

Territorial disputes are often related to the possession of natural

resources

such as rivers, fertile farmland, mineral or oil resources. However, these

disputes can also be driven by culture, religion and ethnic nationalism. The

Transnistria-Moldova conflict has its roots in geopolitical, economical and

environmental motives. Transnistria is a self-declared state; it is

internationally recognized as being part of Moldova, but claims independence

and

maintains some sovereignty with the assistance of Russia. The region has

been de

facto independent since 1991, when it made a unilateral declaration of

independence from Moldova and successfully defeated Moldovan forces, with

Russian assistance. While a ceasefire has held ever since, the Council of

Europe

recognizes Transnistria as a "frozen conflict" region.

2. Description

In many cases territorial disputes result from vague and unclear language

in

a treaty that set up the original boundary. Moldova has a long history as a

border state between great powers, therefore Transnistria can make claims to

a

special political status on historical grounds [8]:

|

Middle Ages to the 20th Century

In the early Middle Ages the region was populated by Slavic tribes

of

Ulichs and Tivertsy as well as by Turkic nomads such as Pechenegs and

the

Polovtsi. A part of Kievan Rus' at times, and a formal part of the

Grand

Duchy of Lithuania in the 15th century, the area came under the

control of

the Ottoman Empire in 1504. It was eventually ceded to the Russian

Empire

in 1792. At that time, the population was sparse and mostly

Moldovan/Romanian and Ukrainian, but also included a nomadic Tatar

population. The end of the 18th century marked the Russian Empire's

colonization of the region, with the aim of defending what was at the

time

the Imperial Russian southwestern border, as a result of which large

migrations were encouraged into the region, including people of

Ukrainian,

Russian, and German nationalities.

Autonomous Republic

In 1918 the Directory of Ukraine proclaimed its sovereignty over

the

left bank of the Dniester. At that time, the population was 48%

Ukrainian,

30% Moldavian, 9% Russian, and 8.5% Jewish. One third of that region

(around Balta) belongs today to Ukraine. In 1922 the Ukrainian SSR was

created, and in 1924 the region became part of the Moldavian ASSR

within

the Ukrainian SSR.

The Moldavian SSR, which was set up by a decision of the Supreme

Soviet

of the USSR on the 2nd of August, 1940, was formed from a part of

Bessarabia taken from Romania on the 28th of June, following the

Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, where the majority of the population were

Romanian speakers, and a strip of land on the left bank of the

Dniester in

the Ukrainian SSR, Transnistria, which was transferred to it in 1940.

In

1941, after Axis Forces invaded Bessarabia in the course of the Second

World War, they advanced over the Dniester river. Romania annexed the

entire region between Dniester and Bug rivers, including the city of

Odessa. However, the Soviet Union regained the area in 1944 when the

Soviet Army advanced into the territory driving out the Axis forces.

Soviet Moldova

The Moldovian SSR became the subject of a systematic policy of

Russification, even more so than in Czarist times. Most industry that

was

built in the Moldavian SSR was concentrated in Transnistria, while the

rest of Moldova had a predominantly agricultural economy. The 14th

Soviet

army had been based there since 1956 and was kept there after the fall

of

the Soviet Union to safeguard what is probably the biggest weapons

stockpile and ammunition depot in Europe, which was set up in Soviet

times

for possible operations in the event of World War III.

|

The Secession

During the last years of the 1980s, the political landscape of the USSR

was

changing owing to Mikhail Gorbachev's policy of perestroika, which allowed

political liberalisation at the regional level. The incomplete

democratization

was preliminary for the nationalism to become the most dynamic political

force.

Some national minorities opposed these changes in the Moldovan political

class

of the republic, since during Soviet times, local politics had often been

dominated by non-Romanians, particularly by those of Russian origin. The

language laws -- introducing the Latin alphabet for written Moldovan --

presented a particularly volatile issue as a great proportion of the

non-Romanian population of the Moldavian SSR did not speak Moldovan. The

problem

of official languages in the Republic of Moldova has become an official

cause

for a conflict, being exaggerated and, perhaps, intentionally politicized.

On the 2nd of September, 1990 the Moldovan Republic of Transnistria was

proclaimed. On the 25th of August, 1991 the Supreme Council of the MRT

adopted

the declaration of independence of the MRT. On the 27th of August, 1991 the

Moldovan Parliament adopted the Declaration of Independence of the Republic

of

Moldova, whose territory included Transnistria. The Moldovan Parliament

asked

the Government of the USSR "to begin negotiations with the Moldovan

Government

in order to put an end to the illegal occupation of the Republic of Moldova

and

withdraw Soviet troops from Moldovan territory".

After Moldova became a member of the United Nations (March 2nd, 1992),

Moldovan President Mircea Snegur authorized concerted military action

against

rebel forces. The rebels, aided by contingents of Russian Cossacks and the

Russian 14th Army, consolidated their control over most of the disputed

area.

The presidents of Moldova and Russia signed an agreement in July of 1992

which

ended the conflict and established a "security zone" controlled by Russian,

Moldovan, and Transnistrian forces. In October of 1994, the Moldovan and

Russian

governments signed another agreement whereby the Russian government agreed

to

withdraw the 14th Army forces from Moldovan territory over a three-year

period.

The Russian State Duma, however, has not approved the agreement and Russian

forces remain in Transnistria. The presidents of Russia and Ukraine brokered

an

agreement in May of 1997 between the Moldovan and Transnistrian governments

which ended the civil war. Under the terms of the agreement, Transnistria

would

remain Moldovan territory unless Moldova decides to reunite with Romania. In

this situation, Transnistria is guaranteed the right to

self-determination.

To view chronology of important historical events and dates of Moldova

and

Transnistria please follow this link.

3. Conflict Duration: 1990-1992

Combat action: June 19th, 1992 to July 21st, 1992 when a cease-fire

agreement

was signed. However, Transnistria is considered to-date to be a "frozen

conflict" region.

4. Location:

Moldova is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, located between Romania to the west and Ukraine to

the

east. Transnistria is a region within Moldova, located between the Dniester

River and the Ukrainian border which covers a territory of 500 square

kilometers

where most of the combat action took place. Geographic

coordinates: 47 00 N, 29 00 E

5. Actors

Local interests

Moldovan officials: the conflict is believed to be

driven by

foreign interests (particularly of Russia) over which Moldova has little or

no

influence. However, Jonathan Goodhand found in his field study that "the

interests vested in the status quo on both sides are stronger than those

wanting

change".

Transnistrian officials: two political camps emerged.

Separatists wish to maintain a "frozen conflict" status, while human rights,

and

free-press advocates hope for political reconciliation.

Local entrepreneurs: conflict is prolonged by the

economic

interests of officials on both sides in the illegal and informal trade,

bribes

at customs posts, and fees charged for licenses and export certificates,

made

possible by the situation. It is said that the annual volume of smuggling

represents the loss to Moldova of the equivalent of more than two annual

government budgets.[6]

General public: Mixed opinions-there are people who live

in

Transnistria and work in Moldova and vice versa. Others have relatives

living

both in Transnistria and Moldova. Many mayors in the north remain in contact

and

co-operate economically, based on pre-independence political and

administrative

ties. Links have been created and supported by third-party mediation

processes

and some economic co-operation occurs between local and regional officials

in

the two parts. [6]

External interests

The Transnistria talks follow a “5-plus-2” format, referring to the five

principal participants involved in the negotiations – Transnistria, the

Republic

of Moldova, Ukraine, the Russian Federation and the OSCE as mediators – plus

the

United States and the European Union as observers.

Russia: Russian policy under Vladimir Putin is not yet

clear, but Russian security interests will certainly continue to be present.

Russian involvement in this conflict is also fed by the Russian interest of

preventing Moldova from becoming too Western-oriented.

Ukraine: some view the Ukraine's new push for closer

ties

with European institutions (NATO and EU) as motivating an interest in being

perceived as helpful in resolving the conflict. It clearly has a stake in

preventing a new war on its border; for example, in 1992, it took in 72,000

refugees from Transnistria.[6]

Romania: One of the countries indirectly interested in

the

conflict is Romania whose main objective is to enter the EU in 2007. The

geographic position of Romania from a strategic point of view makes Romania

a

very interesting consideration in NATO and EU agreements of security. This

strong desire to be part of EU makes the Romanian government worried about

its

proximity to a conflict region. Another important consideration is the

security

pact with NATO and the compromise to guarantee peace in the area. [4]

Recently Romanian President Traian Basescuhas

also

underlined the necessity of launching a new European project-creating a

Black

Sea Euroregion. Therefore, Romania is interested in the unification of

Transnistria and Moldova and further European integration of Moldova.

Transnistria-Moldova relations involve two states and one nation, therefore

Traian Basescu compared current status of the conflict to the example of

Germany's reunification: "We have decided to support the Moldovan

Republic's

efforts to abide by democratic norms and contribute to the consolidation of

regional security. We believe the European Union should provide the Moldovan

Republic with an evolution similar to that for the Western Balkans."[25]

EU and Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe:

EU is determined to keep peace in Europe (especially after the war

in

Yugoslavia) and also to control a number of illegal activities originating

in

Moldova and Transnistria (human, organ and weapon trafficking). EU

also

warned Transnistrian government to impose strict sanctions: one of them

being

the prohibition to all members of Tiraspol (capital of Transnistria)

government

to travel within EU territory. EU also has a strategic interest in

guaranteeing

safe borders to stimulate EU investment in the region. [4]

USA: USA is supporting the idea of a federal state of

Transnistria and Moldova because this would eliminate the double taxation

system

and would increase investment in the area. Another reason to support the

idea of

a federal model is to diminish the presence of Russian troops in the area

and

the threat of Russian control. Another point of interest for the US is

a

strategic one: ending the conflict creates a possibility of establishing

agreements to build military bases near the Russian border. However, at

present

time the US is not involved on either side of the

conflict. [4]

6. Type of Environmental Problem

SOURCE PROBLEMS OF

CONFLICT: DEFORESTATION [DEFOR]

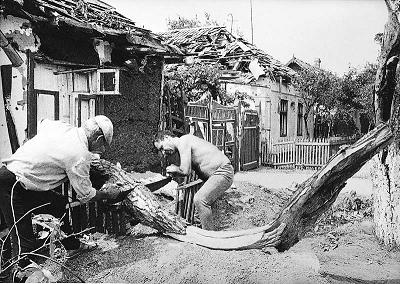

The military conflict between Transnistria and Moldova had a tremendous

impact on the ecosystem of Moldova. The use of modern conventional armaments

and

thousands of refugees escaping the fighting through ecologically delicate

forests tremendously affected the forest system of Moldova.

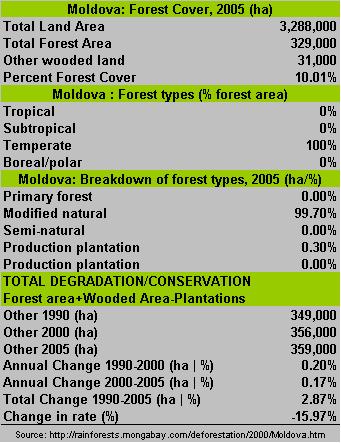

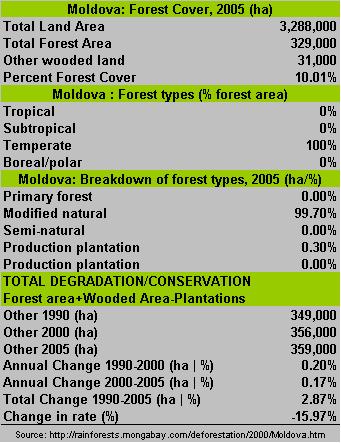

Table 1: Moldova Forest Profile

To view Moldova's profile on forests, grasslands and drylands please

refer to

the Earth Trends Country Profiles.

Moldovan forests suffer from different anthropogenic factors, the most

significant of them being illegal felling and livestock pasturing. There has

been a steady upward trend in such abuses, particularly during the last 12

years, post Transnistria-Moldova conflict.

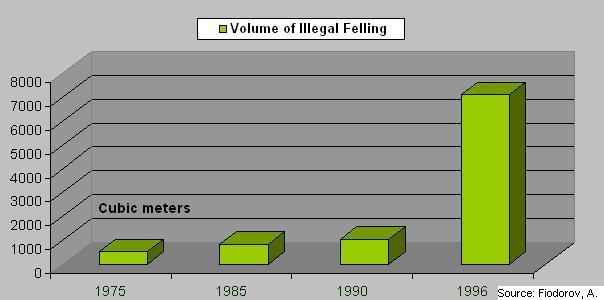

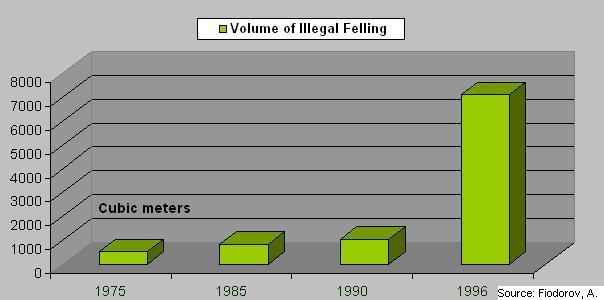

Figure 1: Volume of Illegal Felling

According to the official statistics generated by the Moldsilva State

Forestry Association, the total volume of registered illegal felling in the

forests managed by state forestry enterprises constituted 515 in 1975, 826

in

1985, 1,048 in 1990, and 7,096 cubic meters of wood in 1996. Probably, the

actual volume of illegal felling is much higher.[5]

|

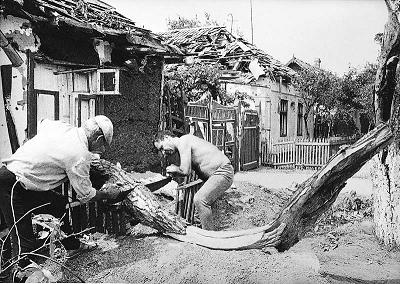

Dependent almost completely on unreliable

energy

supplies from Russia and Transnistria, a major energy crisis initiated

years of uncontrolled tree cutting (1992-1995) not only in the

forests,

but in nature reserves, floodplain forests, parks, and streets of

large

cities. Even vineyards and orchards have been cut down for fuel wood,

creating serious soil erosion. The overall increase in the volume of

unauthorized felling in Moldovan forests can be explained mainly by

the

inability of most villagers to pay for firewood needed for heating

purposes. There has been a steady upward trend in illegal felling

cases,

particularly during the last 12 years, post Transnistria-Moldova

conflict.[5] |

7. Type of Habitat: Temperate

Moldova's climate is moderately continental: the summers are warm and

long,

with temperatures averaging about 20°C, and the winters are relatively mild

and

dry, with January temperatures averaging -4°C. Annual rainfall, which ranges

from around 600 millimeters in the north to 400 millimeters in the south,

can

vary greatly; long dry spells are not unusual. The heaviest rainfall occurs

in

early summer and again in October; heavy showers and thunderstorms are

common.

Because of the irregular terrain, heavy summer rains often cause erosion and

river silting.

8. Act and Harm Sites: Moldova

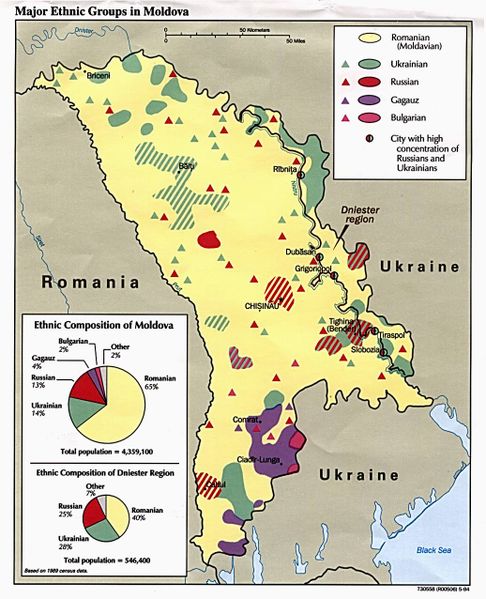

Dispute Triggers in Transnistria-Moldova Conflict

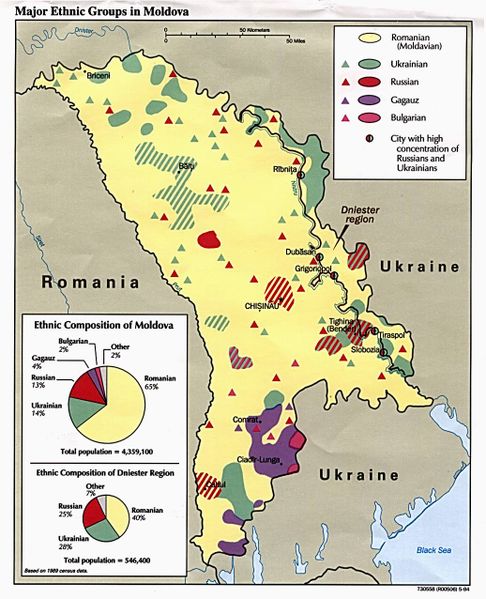

Although having a distinctive national aspect, the Transnistria region

conflict can not be defined as solely an ethnic conflict. To the extent that

the

conflict surfaces in Western media, it is usually portrayed as a conflict

between an enclave inhabited by ethnic Russians and the largely ethnic

Romanian

Moldova. However, this is just not the case. The approximately 4,5 million

people in the Republic of Moldova, including Transnistria, consists of

approximately 60% Moldovans, 14% Ukrainians, and 13% Russians, as well as

other

smaller groups like the Christian Turkish Gagauz. This is not very different

in

Transnistria, where Moldovans make up 40%, Ukrainians 28% and Russians 23%

of a

population of 500,000. [23]

|

The causes of the conflict are complex, involving ethnic factors

and,

above all, maneuvering for power and wealth among elite groups.

Interethnic conflict in Moldova produced results similar to those

that

followed outbreaks of violence in other former republics of the Soviet

Union soon after they had proclaimed their independence. The

Transnistrian

“frozen conflict”, so-called because no progress has been made on

resolving the conflict in the past decade, mirrors other secessionist

conflicts in Georgia (Abhazia, Adjaria and South Ossetia) and

Azerbaijan

(Nagorno-Karabakh).

There are two main sources that feed the roots

of

these conflicts:

(1) Russia’s post-cold-war ambitions to retain

control over ex-republics through puppet regimes, and

(2) the huge

profits made from illicit drugs and human trafficking and smuggling of

arms from the ex-USSR military hardware depots.

The beneficiaries

of

such profits are the main advocates of the status quo in Transnistria,

Abhazia and South Ossetia. While attempting to gain a camouflaged

legalization of the secession, and eventually join these enclaves to

the

Russian Federation, the supporters of these regimes initiated a

“confederation” project that would in reality dismantle sovereign

countries like Georgia, Moldova, and Azerbaijan.[1]

Separatism movement was used with the aim of achieving

geopolitical

interests that usually harmonize with criminal ones. Transnistria has

become a hub for criminal activities, drug smuggling, and arms and

human

trafficking to Western Europe and the Middle East. [24]

The

international community treats political regime of Transnistria as

anti-democratic and authoritarian and considers Transnistria an outlaw

state governed by criminals. |

An appropriate background was necessary in order to

intensify tensions in the Transnistria-Moldova Conflict:

1. Creation of a permanently unstable zone (is a part of

the

methodology called the controlled chaos concept). It enables causing tension

on

a certain territory, thus, creating possibilities for influencing states and

international structures. The area of the region depends on the

geo-political,

geo-strategic, and geo-economic significance of the controlled region on the

one

hand, and on the cultural and information level typical for the region on

the

other.

2. Creation of serious obstacles in the

implementation of the concept of the unification of Romania and the

Bessarabian

and Transnistrian region. Any version of such a concept stipulates the

liquidation of the Russian military presence. Besides the de facto outdated

but

still important considerations of the military and strategic nature, the

loss of

control over the Bessarabian and Transnistrian region, in the eyes of the

considerable Russian military and political establishment, means a kind of

"official lowering of the flag" of Russia as a super-power in the so-called

Eurasian conception of this term followed by latter.

3. Creation of a territory that does not comply with the

internationally acknowledged norms and criteria, thus, allowing benefiting

from

certain economic advantages, and providing the possibility to carry out

different illegal special operations.[2]

Many analysts are convinced that a key factor obstructing a settlement is

the

personal interests of the leaders of Transnistria and Moldova, Russia and

Ukraine who profit from illegal activities that take place in Transnistria.

These activities include illicit arms sales, human trafficking of women and

girls and smuggling. Recently, a cache of 70 surface-to-air missile

launchers

disappeared from a former Soviet stockpile and officials are unable to

account

for their whereabouts. Moreover, there were reports that Russian troops in

Chechnya used illegally produced weapons in Transnistria.[12]

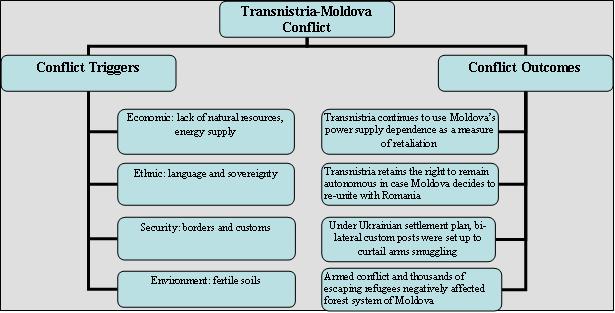

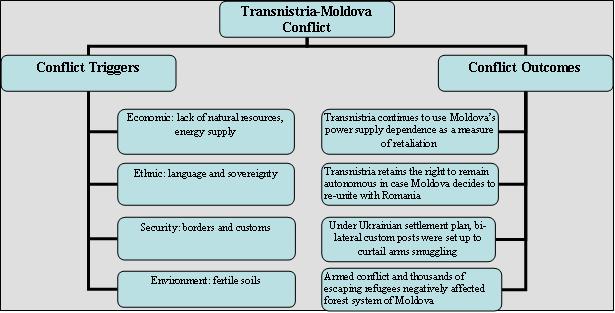

Figure 2: Conflict Triggers and Outcomes

Economic triggers of the Transnistria-Moldova

conflict

The Republic of Moldova is a landlocked country with access to the Black

Sea

via the Dniester river and is situated between Romania and Ukraine. Harvard

Professor of Economics Dani Rodrik believes that geography has a significant

impact on a country's economic performance. Geography and lack of natural

resources can also be traced back to the roots of the Transnistria-Moldova

conflict. Despite, the country's chief assets of a mild climate and fertile

soils (1.7 million hectares of arable land in 1991), the economic growth is

stagnant, mainly because the economy is based solely on agriculture and

products

including vegetables, fruits, wine, grain, sugar beets, sunflower seed,

tobacco,

beef, and milk.

The country's lack of fuels and minerals significantly increases

Moldova's

trade deficit and makes the country heavily reliant on Russia for fuel

supplies.

This dependence intensifies Russia's key role in the Transnistria-Moldova

conflict. Russian energy subsidies to Transnistria, estimated to be worth

approximately $20 million annually, are almost the equivalent of the budget

of

the Transnistrian government. [23] The

dependence of

Moldova on energy supplies from Russia provides the latter with further

political leverage. In addition, some experts have expressed concern about

alleged Russian efforts to extend its hegemony over Moldova through

manipulation

of Moldova's relationship with its breakaway Transnistria region and energy

supplies. The strategic importance of Transnistria region to Moldova can

also be

attributed to the energy dependence of Moldova: 90% of power and 100% of

power

transformers are produced in Transnistria. Moreover, Transnistria's

authorities

have frequently disrupted the flow of fuels into Moldova from Russia and

Ukraine.[10]

Environmental triggers of the Transnistria-Moldova conflict:

Fertile Soils

Roughly three-fourths of the land area of Moldova or around 2.5 million

ha is

covered with chernozem (black earth, a variety of soil rich in organic

matter in

the form of humus) which is Moldova's main natural resource and the main

reason

for the agricultural orientation of the country's economy. No other country

in

the world has such a high share of chernozems. Throughout the long history

of

agricultural development on Moldovan lands, the natural process of soil

erosion

has been accelerated by improper agricultural practices and unsustainable

soil

management including inappropriate cultivation methods, the destruction of

original natural vegetation, clean cultivation, overgrazing, excessive

fertilization and irrigation and many others.

It has been estimated that at least 1,500,000 ha or around 59% of

Moldovan

agricultural lands are threatened with erosion. In some regions of the

country,

as much as 95% of agricultural land area can be eroded. At present, the area

of

eroded soil is over 850,000 ha, or one-third of agricultural lands,

including

two-thirds of arable land. More than 350,000 ha of agricultural land is

seriously affected by erosion, which resulted in the 40-60% loss of soil

productivity. The eroded area grows by 0.5-1% a year. The annual loss of

fertile

soil particles and humus amounts to about 20-25 million tons and 600,000

tons,

respectively. No doubt, soil erosion has long been recognized as a major

environmental problem in Moldova.[5] Considering the

facts of the fast rate of the soil erosion, the expansion of the fertile

soils

territory is vital to sustain the agricultural output and the fragile

economic

growth. In Transnistria, chernozems (fertile soils) occupy more than 90% of

the

total land area. Therefore, the fertile soils of the Transnistria region

represent strategic agricultutral interests of Moldova.

9. Type of Conflict: Civil War

10. Level of Conflict: Intrastate

The violence broke out in the fall of 1990. The Transnistrian "Republican

Guard" began to take over police stations, administrative bodies, schools,

radio

stations and newspapers. On December 13th, 1991 Moldovan police for the

first

time returned fire in defending the regional government building in

Dubossary.

The clashes renewed on March 1st, 1992. All efforts among Moldova, Russia,

Ukraine, and Romania to mediate the conflict failed. President Mircea Snegur

declared a state of emergency on March 28th, 1992. However, the conditions

took

a sharp turn to the worse in May of 1992 as the government made an effort to

disarm the paramilitary formations and escalated into a full-scale civil war

in

the city of Bendery on June 19th, 1992. After two days' fierce fighting, the

Moldovan units were driven out from the city. Moldovan President Mircea

Snegur

declared on June 22nd, 1992 that "we are at war with Russia".

On July 21st, 1992, an agreement was signed in Moscow between the

Republic of

Moldova and the Russian Federation on principles of a peaceful solution of

the

armed conflict in the Transnistrian region of Moldova. The agreement

provided

for an immediate ceasefire and the creation of a demilitarized security zone

between the parties, 10 km left and right of the Dniestr, including also the

city of Bendery. The trilateral peacekeeping troops (5 Russian, 3 Moldovan

and 2

Transnistrian battalions) began deployment on July 29th, 1992.

11. Fatality Level of Dispute (military and civilian fatalities)

Short but bloody conflict resulted in more than 700 deaths, 1,000 wounded

and

100,000 refugees. The detailed timeline of the events preceding the outbreak

of

combat actions can be further viewed

here.

12. Environment-Conflict Link and Dynamics:

Aside from ethnic, economic and security reasons, Transnistria-Moldova

conflict can be depicted in the following diagram:

Diagram 1: Environment-Conflict Link and Dynamics

13. Level of Strategic Interest: State and Regional

For most of the duration of armed dispute in Transnistria, the level of

strategic interest was State and Regional. The conflict mostly concerned

separatist movement of Transnistria and the Moldovan government and army.

Today

the conflict borders on a multilateral level of strategic interest because

of

the conflict settlement involvement of Russia, Romania, Ukraine, EU, and the

US.

14. Outcome of Dispute: Stalemate

Despite the fact that on July 21st, 1992 a cease-fire agreement was

signed,

the Council of Europe recognizes Transnistria as a "frozen conflict"

region.

July 21st, 1992 agreement signed in Moscow between the Republic of

Moldova

and the Russian Federation provided for an immediate ceasefire and the

creation

of a demilitarized security zone between the parties, 10 km left and right

of

the Dniester River, including also the city of Bendery.

The agreement set out principles for a peaceful solution of the conflict,

including:

- Respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Moldova

- The need for a special status of the left-bank Dniester region, and

- The right of the population of the left bank to decide on its own

future

if Moldova were to reunite with Romania.

Agreement also provided for trilateral peacekeeping forces, consisting of

5

Russian, 3 Moldovan and 2 Transnistrian battalions. However, this agreement

violates the international laws of peacekeeping. According to international

law,

peacekeeping forces must be composed of neutral forces. Despite this

inconsistency with international laws, the peacekeeping troops began

deployment

on July 29th, 1992. The cease-fire has largely been observed until the

present,

although numerous incidents in the security zone guarded by the trilateral

forces have been alleged by both sides.

Another proposal for reconciliation of the conflict is a so-called

Primakov

Plan (September, 2000). It called for the creation of a "common state" made

up

of "federative and confederative" ideas but weighed heavily toward

Transnistria's goals. Under this draft each side would be allowed to

maintain

its own constitution, legislative, executive, and judicial bodies, flag,

coat of

arms, and national anthem. Each would also have its own army, security

police,

and regular police that would not be able to operate on the other's

territory

without their consent. The common state would have jurisdiction over foreign

policy, economic policy, and border guards with no internal customs.

At first both sides strongly denounced the plan, with Moldova saying it

could

not agree to the country's "federalization" and Transnistria claiming that

any

rapprochement must be between virtually independent states.[16]

Recent

Developments:

In the summer of 2004, the Transnistrian authorities forcibly closed six

schools that taught Moldovan language using the Latin script. About 3,400

enrolled children were affected by this measure and the teachers and parents

who

opposed the closures were arrested. During the crisis, the Moldovan

government

decided to create a blockade that would isolate the autonomous republic from

the

rest of the country. The blockade was ineffective because of a lack of

cooperation from Ukraine's government. Transnistria retaliated by a series

of

actions meant to destabilize the economic situation in Moldova, in

particular,

by cutting the power supply from the power plants, which caused power

outages in

parts of Moldova.

Moldova's viewpoint of solution: departing from previous plan to include

Transnistria as a province of Moldova. Chisinau now proposes forming a

federation with Transnistria with conditionalities attached - retirement of

the

Russian army and demilitarization of Transnistria.

Transnistria now supports the idea of a federal state: two equal states

and a

common parliament formed by federative organs of power. Each state would

have

their own customs authority, army and departments dealing with licensing,

trade

and industry. This is one of the most important point of negotiation for

Transnistria, due to the fact that each time investors try to implement

economical activities in Transnistria they have to suffer a double tax

system,

paying for exports and license two times: one toTransnistria and another one

to

Moldova that do not recognize the authority of Transnistria. Transnistria

has

also suggested that the official languages should be Russian, Moldavian and

Ukrainian.

Ukraine proposed a seven-point plan in May of 2005 by which the

separation of

Transnistria and Moldova would be settled through a negotiated settlement

and

free elections. Under the plan, Transnistria would remain an autonomous

region

of Moldova.

Strategies to resolve the conflict:

Members of Moldovan civil society proposed 3D Strategy,

a

plan that provides specific policy recommendations for governments and

multilateral organizations, and provides citizens with the opportunity to

have

input in the future viability of their country. The plan calls for the

implementation of three principles:

Demilitarization-withdrawal of the Russian troops and

decommissioning of military plants and disarmament of the Transnistrian

military

and security forces;

Decriminalization-curbing and suppressing the rampant

contraband, arms and human trafficking, and other criminal activities;

Democratization-ensuring a free flow of information and

freedom of speech; implementing international human rights standards; and

promoting rule of law.

The success of this strategy will depend not only on the political will

of

the government of Moldova; it also needs the support and engagement of the

West-the EU, the OSCE and the United States-and Moldova’s neighbors-Ukraine,

Romania and Russia. All of these parties have a vested interest in ensuring

a

climate of regional security and stability.

The 3D Strategy outlines key

objectives to be met by 2012. They include expanding negotiation talks to

encompass the EU, the US and Romania, in addition to the current roster of

Russia, Ukraine, the OSCE, and Moldova, and removing negotiators from the

Transnistrian leadership. The plan also recommends establishing an

International

Executive Council that would monitor progress toward settling the conflict,

and

an International Civil Provisional Administration to help govern Moldova’s

eastern districts. In addition, the 3D Strategy calls for assigning Tiraspol

special status as a free economic zone with rights to self-government under

a

free-city model.[1]

15. Related ICE Cases associated with Territorial

Disputes:

Territorial dispute over rivers and water territory:

Conflict between Israel and Lebanon over the Litani River: LITANI

In 1980 war erupted between Iran and Iraq over control of the

Shatt-al-Arab

waterway: IRANIRAQ

Political conflicts between Egypt and Sudan over sharing of the Nile

waters:

NILE

and BLUENILE

Conflict between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, both Southern Indian States,

over

Cauvery River for water supply: CAUVERY

The struggle for fresh water in the Middle East as a primary cause of the

1967 Arab-Israeli war: JORDAN

Territorial dispute over mineral

resources:

Conflict between Chad and Libya over uranium deposits: AOUZOU

The

territorial dispute between the former Soviet Union and China can be traced

back

to the 17th century which was triggered by rumors of fur, gold, and silver:

USSURI

Territorial dispute over oil resources:

The 1982 war over the Falkland/Malvinas Islands between Argentina and

Britain

over oil reserves within Islands' territorial waters: FALK

The

province of Aceh has a long tradition of resisting the Indonesian central

government in Jakarta. This resistance began as a religious movement, but

acquired a different tone once Mobil Oil Indonesia (MOI) discovered a vast

wealth of oil and natural gas deposits in Lhok Seumawe, North Aceh in 1971:

ACEH

Territorial dispute over land:

Armed dispites between the Peru and Ecuador for over one hundred and

fifty

years over The Cordillera del Condor: PERUEC

Conflict between El Salvador and Honduras over

lack

of land: SOCCER

Territorial dispute over culture, religion and ethnic

nationalism:

On April 10, 1998 Russia cut oil exports through Latvia in a dispute over

the

discrimination of the ethnic Russians in Latvia: LATVIAOIL

Territorial dispute between India and China for Arunachal Pradesh region

over

culture and religion: INDIA-CHNA

The civil war in the Sudan is routinely characterized as a conflict

between

Muslims and Christians, Arabs and Africans, or North and South. Religion,

ethnicity, economic and regional issues are the key triggers of the

conflict: SUDAN

Ethnic dispute in West Kalimantan between the Christian Dayaks and the

Moslem

Madurese. The conflict commenced mainly as a result of the Indonesian

Government's "transmigration plan." This program, which began in the 1930's,

moved people from the populated islands such as Java (Madura Island), to the

less populated islands of Irian Jaya and Kalimantan: KALIMAN

Territorial dispute between Azerbaijan and Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh

region, located in Azerbaijan: NAGORNO

Territorial dispute between Georgia and Russia.

Ossetia's territory currently straddles the political divide between North

Ossetia-Alania in Russia, and South Ossetia in Georgia. The Ossetians

consider

themselves to be a separate ethnic group from either the Georgians or the

Russians: OSSETIA

Possible venues for further research of territorial

disputes:

Finnish Karelia, Petsamo, Salla, Kuusamo, some islands of Gulf of

Finland:

Russia and Finland (not governmental level debate)

Golan Heights: Syria

and

Israel (Shebaa Farms claimed by Lebanon and controlled by Israel)

Hans

Island: Canada and Denmark

Ivangorod: Russia and Estonia

Olivenza:

Spain

and Portugal

Pechorsky District of the Pskov Oblast: Russia and Estonia

Pedra Branca: Singapore and Malaysia

Pytalovsky District of the

Pskov

Oblast: Russia and Latvia

Sabah (North Borneo): Philippines and Malaysia

Snake Island: Ukraine and Romania

Tromelin: France and Mauritius

Vozrozhdeniya Island (see Aral Sea) : Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan

Black

Hills: United States government and the Lakota Nation

Northern Cyprus:

Republic of Cyprus and Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

Western

Armenia,

Van Province, Kars: Armenia and Turkey

For a complete listing of the

current

international disputes please consult CIA World Factbook

16. Relevant Websites and Literature

-

3D Plan to Address the Frozen Conflict in

Transnistria, Brussels, February 18th , 2005, http://foundation.moldova.org/pagini/eng/125 and http://www.moldova.org/pagini/eng/122/

-

Asarov, Boris, Kosovo versus Transnistria,

Moldova

Azi, Mar 13, 2006, http://www.azi.md/investigation?ID=38404

-

Commission of the European Communities, Commission Staff Working

Paper,

European Neighborhood Policy, Country Report: Moldova, Dec 5,

2004

-

Delgado, Talia, Transnistria, The Forgotten

Conflict, Apr 23, 2005

-

Fiodorov, Andrei , Facing Environmental Problems: the

Case of the Republic of Moldova, Journal of Eurasian Research, http://www.actr.org/JER/issue6/7.htm

-

Goodhand, Jonathan, Conflict Assessments, A Synthesis

Report: Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Nepal and Sri Lanka, Centre for Defense

Studies King's College, University of London

-

Hagmann, Tobias, Confronting the Concept of Environmentally Induced

Conflict, Peace, Conflict and Development, Issue Six, January

2005

-

http://encyclopedia.thefreedictionary.com/Transnistria

-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transnistria

-

http://www.photius.com/countries/moldova/economy/moldova_economy_energy_and_fuels.html

-

Iovu, Tudor, http://www.foto.md/persgal.php?gid=13&action=showphotos&puid=4

-

ITAR-TASS, Trans-Dniester Region Denies Exporting

Weapons to Chechnya, Feb 1, 2001

-

LEAD, The Sustainability of Societies in Transition: Agrarian

Reform

and Sustainable Agriculture in Moldova, December, 2004

-

Nantoi, Oazu, The Frozen Conflict in Transnistria: Presentation in

Washington, Institute of Public Policies, Jan 14, 2005

-

National Human Development Report - 1996, State Building and

Integration of Society, Republic of Moldova

-

Quinlan, Paul D, Moldova under Lucinschi,

Demokratizatsiya, Winter 2002, http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3996/is_200201/ai_n9062110/pg_5

-

Ross, Michael, Natural Resources and Civil War: An Overview with

Some

Policy Options, Dec 13, 2002

-

Skordas, Achilles, Transnistria: Another Domino on Russia's

Periphery?, Yale Journal of International Affairs, Summer/Fall

2005

-

Spanu, Vlad, Why is Moldova Poor and Economically Volatile?,

Dec

21, 2004, http://foundation.moldova.org/pagini/eng/822/

-

The Economist Print Edition, The Hazards of a Long, Hard

Freeze,

Aug 19, 2004

-

Transdniestrian Conflict, Origins and Main Issues, Based on the

Background Paper "The Transdniestrian Conflict in Moldova: Origins and

Main

Issues", CSCE Conflict Prevention Centre, Vienna, June 10, 1994, http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/13611.pdf

-

Transnistria, The Forgotten Conflict, http://www.brain-storming.info/article.php?ida=70

-

Vahl, Marius, Borderland Europe(11): Transforming

Transnistria?, Jan 9, 2005

- Woehrel, Steven, CRS Report for Congress, Moldova:

Background and U.S. Policy, Updated March 8, 2005

- www.kross.ro/transdniestria_map

For use of this background, please link to GRSites

Feel free to contact me with

your

questions or recommendations.

Wednesday April

12,

2006 4:30 PM